Aquaporins (AQPs) are water channel proteins that are essential to life, being expressed in all kingdoms. In humans, there are 13 AQPs, at least one of which is found in every organ system. The structural biology of the AQP family is well-established and many functions for AQPs have been reported in health and disease. AQP expression is linked to numerous pathologies including tumor metastasis, fluid dysregulation, and traumatic injury. The targeted modulation of AQPs therefore presents an opportunity to develop novel treatments for diverse conditions. Various techniques such as video microscopy, light scattering and fluorescence quenching have been used to test putative AQP inhibitors in both AQP-expressing mammalian cells and heterologous expression systems. The inherent variability within these methods has caused discrepancy and many molecules that are inhibitory in one experimental system (such as tetraethylammonium, acetazolamide, and anti-epileptic drugs) have no activity in others. Some heavy metal ions (that would not be suitable for therapeutic use) and the compound, TGN-020, have been shown to inhibit some AQPs. Clinical trials for neuromyelitis optica treatments using anti-AQP4 IgG are in progress. However, these antibodies have no effect on water transport. More research to standardize high-throughput assays is required to identify AQP modulators for which there is an urgent and unmet clinical need.

[This entry is an extract from our open access publication, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1589; doi:10.3390/ijms20071589]

Aquaporins (AQPs) are water channel proteins that are essential to life, being expressed in all kingdoms. In humans, there are 13 AQPs, at least one of which is found in every organ system. The structural biology of the AQP family is well-established and many functions for AQPs have been reported in health and disease. AQP expression is linked to numerous pathologies including tumor metastasis, fluid dysregulation, and traumatic injury. The targeted modulation of AQPs therefore presents an opportunity to develop novel treatments for diverse conditions. Various techniques such as video microscopy, light scattering and fluorescence quenching have been used to test putative AQP inhibitors in both AQP-expressing mammalian cells and heterologous expression systems. The inherent variability within these methods has caused discrepancy and many molecules that are inhibitory in one experimental system (such as tetraethylammonium, acetazolamide, and anti-epileptic drugs) have no activity in others. Some heavy metal ions (that would not be suitable for therapeutic use) and the compound, TGN-020, have been shown to inhibit some AQPs. Clinical trials for neuromyelitis optica treatments using anti-AQP4 IgG are in progress. However, these antibodies have no effect on water transport. More research to standardize high-throughput assays is required to identify AQP modulators for which there is an urgent and unmet clinical need.

- Aquaporin

- AQP inhibitors

- AQP modulators

- AQPs in disease

- TGN-020

- heavy metals

- small molecule inhibitors

1. Aquaporin Inhibitors

Aquaporin Inhibitors

[This entry is an extract from our open access publication, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1589; doi:10.3390/ijms20071589]

Most of the molecules that are currently under investigation as aquaporin (AQP) inhibitors target AQPs 1, 2, 3 or 4. There are many patents, clinical trials, and studies on AQP up-regulators, modulators, and inhibitors. For the purposes of this review, only AQP inhibitors are considered (Table 1).

Table 1. Currently-available AQP inhibitors, their structures, the AQPs they inhibit (species are highlighted as h—human, m—mouse, and r—rat) and the conditions under which they were assayed.

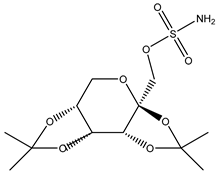

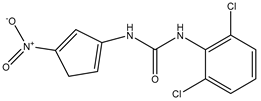

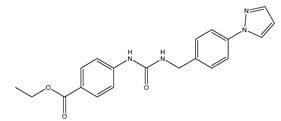

Currently-available AQP inhibitors, their structures, the AQPs they inhibit (species are highlighted as h—human, m—mouse, and r—rat) and the conditions under which they were assayed.| Inhibitor | Conditions | AQPs Inhibited | Structure | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

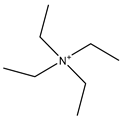

| Tetraethyl-ammonium | Xenopus | oocytes 100 µM |

hAQP1 |  |

[1] | (Brooks, Regan et al. 2000, Müller, Hub et al. 2008) | |

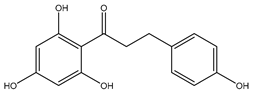

| Phloretin | Xenopus | oocytes 0.1 mM Proteoliposomes 0.5 mM |

rAQP9 hAQP3 |

|

[2][3] | (Tsukaguchi, Shayakul et al. 1998, Müller-Lucks, Gena et al. 2013) | |

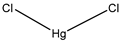

| Mercury chloride | Xenopus | oocytes 1 mM |

hAQP1 |  |

[4][5] | (Preston, Carroll et al. 1992, Preston, Jung et al. 1993) | |

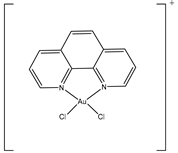

| AuPhen | Erythrocytes 50 µM Adipocytes 15 µM |

hAQP3 hAQP7 |

|

[6][7] | (Martins, Marrone et al. 2012, de Almeida, Soveral et al. 2014) | ||

| Silver nitrate | Erythrocytes 10 µM |

hAQP3 |  |

[8] | (Niemietz and Tyerman 2002) | ||

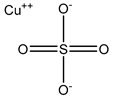

| Copper sulfate | Swan 71 cells 100 µM |

hAQP3 |  |

[9] | (Alejandra, Natalia et al. 2018) | ||

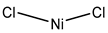

| Nickel chloride | Human bronchial epithelium cells 1 mM |

hAQP3 |  |

[10] | (Zelenina, Bondar et al. 2003) | ||

| Furosemide | Xenopus | oocytes 10 µM |

hAQP1 |  |

[11] | (Ozu, Dorr et al. 2011) | |

| Bumetanide | Xenopus | oocytes 100 µM |

rAQP4 |  |

[12] | (Migliati, Meurice et al. 2009) | |

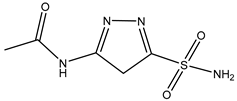

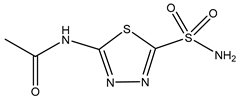

| N | -(5-Sulfamoyl-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl) acetamide | Xenopus | oocytes 20 µM |

hAQP4-M23 |  |

[13] | (Tsutomu Nakada 2010) |

| IMD-0354 | Mice 0.76 mg/kg |

mAQP4-M23 |  |

[14] | (Pelletier 2017) | ||

| Acetazolamide | HEK293 cells 10 µM |

rAQP1 rAQP4 |

|

[15] | (Gao, Wang et al. 2006) | ||

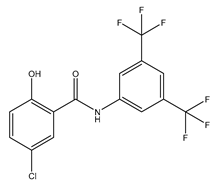

| TGN-020 | C57/BL6 male mice 200 mg/kg (23–28 g) |

mAQP4 |  |

[16] | (Igarashi, Huber et al. 2011) | ||

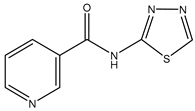

| Topiramate | Xenopus | oocytes 20 µM |

rAQP4-M23 |  |

[17] | (Huber, Tsujita et al. 2009) | |

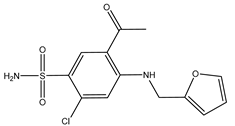

| DFP00173 | Human erythrocytes 25 µM |

hAQP3 |  |

[18] | (Sonntag, Gena et al. 2019) | ||

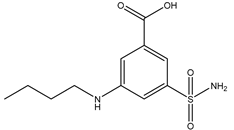

| Z433927330 | Human erythrocytes 25 µM |

mAQP7 |  |

[18] | (Sonntag, Gena et al. 2019) |

Several molecules have been suggested as inhibitors of various AQPs over the past few years. Of these, most are small molecules (Table 1). The similarity found between AQPs and ion channels has caused interest in ion channel modulators as possible AQP inhibitors [19]. Arylsulfonamides such as acetazolamide are molecules that have attracted attention as potential AQP inhibitors [20]. Anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) have also been suggested to have an AQP modulating function [21]. However, they have yet to be proven as definitive AQP inhibitors. A novel molecule named TGN-020 has shown great promise very recently as an inhibitor in mouse models [16]. Micro RNA (miRNA) and small interfering RNA (siRNA) have also been used to modulate AQPs [21]. Mercury chloride binds to a pore-lining cysteine residue found on several (but not all) AQPs and blocks the channel [22]. Mercury and its compounds is known to be toxic due to their non-specificity which causes many off-target effects [23]. Other heavy metal compounds (such as silver and gold compounds) have been investigated as inhibitors, but the challenge is finding a molecule with a side-effect profile that is tolerable. Currently-known inhibitors are discussed by type in the sections below.

Several molecules have been suggested as inhibitors of various AQPs over the past few years. Of these, most are small molecules (Table 1). The similarity found between AQPs and ion channels has caused interest in ion channel modulators as possible AQP inhibitors (Jeyaseelan, Sepramaniam et al. 2006). Arylsulfonamides such as acetazolamide are molecules that have attracted attention as potential AQP inhibitors (Yang, Zhang et al. 2008). Anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) have also been suggested to have an AQP modulating function (Tang and Yang 2016). However, they have yet to be proven as definitive AQP inhibitors. A novel molecule named TGN-020 has shown great promise very recently as an inhibitor in mouse models (Igarashi, Huber et al. 2011). Micro RNA (miRNA) and small interfering RNA (siRNA) have also been used to modulate AQPs (Tang and Yang 2016). Mercury chloride binds to a pore-lining cysteine residue found on several (but not all) AQPs and blocks the channel (Verkman, Anderson et al. 2014). Mercury and its compounds is known to be toxic due to their non-specificity which causes many off-target effects (Castle 2005). Other heavy metal compounds (such as silver and gold compounds) have been investigated as inhibitors, but the challenge is finding a molecule with a side-effect profile that is tolerable. Currently-known inhibitors are discussed by type in the sections below.

1.1. Small Molecule Inhibitors

1. Small Molecule Inhibitors

Tetraethylammonium (TEA) is a small molecule inhibitor that was first tested due to perceived similarities between AQPs and ion channels. Using human AQP1 expressed in

Xenopus oocytes, a maximum single dose of 10 mM TEA caused a reduction in water permeability of 33% [24]. Another study using 4 µM and 100 µM TEA showed an inhibition of 44% for

oocytes, a maximum single dose of 10 mM TEA caused a reduction in water permeability of 33% (Brooks, Regan et al. 2000). Another study using 4 µM and 100 µM TEA showed an inhibition of 44% for

Xenopus oocytes expressing AQP1, with no differences at the two concentrations; TEA also inhibited AQP2 and AQP4, with maximal inhibition of 40% and 57%, respectively, at 100 µM TEA [25]. Further testing of TEA in

oocytes expressing AQP1, with no differences at the two concentrations; TEA also inhibited AQP2 and AQP4, with maximal inhibition of 40% and 57%, respectively, at 100 µM TEA (Detmers, de Groot et al. 2006). Further testing of TEA in

Xenopus oocytes or in native AQP1-expressing erythrocytes has failed to show inhibition (Søgaard and Zeuthen 2008, Verkman, Anderson et al. 2014). TEA is thought to act by binding to a tyrosine residue located on the extracellular end of transmembrane helix 5 [25].

oocytes or in native AQP1-expressing erythrocytes has failed to show inhibition (Søgaard and Zeuthen 2008, Verkman, Anderson et al. 2014). TEA is thought to act by binding to a tyrosine residue located on the extracellular end of transmembrane helix 5 (Detmers, de Groot et al. 2006).

Acetazolamide is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor used in glaucoma to reduce aqueous humor production and hence intraocular pressure [26]. It has been shown to be a reversible inhibitor of AQP1 and AQP4 (Table 1). It has inhibitory effects on

Acetazolamide is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor used in glaucoma to reduce aqueous humor production and hence intraocular pressure (Pastorekova, Parkkila et al. 2004). It has been shown to be a reversible inhibitor of AQP1 and AQP4 (Table 1). It has inhibitory effects on

Xenopus oocytes expressing human AQP4 in a dose-dependent manner with maximal inhibition of 85% at the highest dose of 20 µM [27]. A reduction in the water permeability of rat AQP4 (assayed in proteoliposomes) to 46% was observed at a maximum dose of 1.25 mM acetazolamide [28]. In HEK293 cells expressing rat AQP1, there was a 39% reduction in water permeability with 100 µM acetazolamide compared to untreated rat AQP1 (using GFP fluorescence to measure swelling) [15]. However, acetazolamide appears to be unable to inhibit endogenous AQPs in human cells [29][30].

oocytes expressing human AQP4 in a dose-dependent manner with maximal inhibition of 85% at the highest dose of 20 µM (Huber, Tsujita et al. 2007). A reduction in the water permeability of rat AQP4 (assayed in proteoliposomes) to 46% was observed at a maximum dose of 1.25 mM acetazolamide (Tanimura, Hiroaki et al. 2009). In HEK293 cells expressing rat AQP1, there was a 39% reduction in water permeability with 100 µM acetazolamide compared to untreated rat AQP1 (using GFP fluorescence to measure swelling) (Gao, Wang et al. 2006). However, acetazolamide appears to be unable to inhibit endogenous AQPs in human cells (Yang, Kim et al. 2006, Søgaard and Zeuthen 2008).

Anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) have also been suggested as possible AQP inhibitors [17]. Their anti-epileptic action has been hypothesized take place through modulation of AQPs. Many AEDs such as topiramate, zonisamide, and lamotrigine are known to have a similar inhibitory effect to acetazolamide on carbonic anhydrase enzyme as well as an in silico predicted binding site on AQP4 that is similar to that hypothesized for acetazolamide [17]. AEDs had an inhibitory effect on AQP4 in

Anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) have also been suggested as possible AQP inhibitors (Huber, Tsujita et al. 2009). Their anti-epileptic action has been hypothesized take place through modulation of AQPs. Many AEDs such as topiramate, zonisamide, and lamotrigine are known to have a similar inhibitory effect to acetazolamide on carbonic anhydrase enzyme as well as an in silico predicted binding site on AQP4 that is similar to that hypothesized for acetazolamide (Huber, Tsujita et al. 2009). AEDs had an inhibitory effect on AQP4 in

Xenopus oocytes [17], however, this could not be reproduced in rat thyroid epithelial cells [20]. AEDs are thought to possibly have an inhibitory effect on AQP1, AQP4, and AQP5 [31]. However due to their unconfirmed mechanisms of action and relatively non-specific action, there is no conclusive evidence showing that AEDs are effective and safe AQP inhibitors [32][33].

oocytes (Huber, Tsujita et al. 2009), however, this could not be reproduced in rat thyroid epithelial cells (Yang, Zhang et al. 2008). AEDs are thought to possibly have an inhibitory effect on AQP1, AQP4, and AQP5 (Shank and Maryanoff 2008). However due to their unconfirmed mechanisms of action and relatively non-specific action, there is no conclusive evidence showing that AEDs are effective and safe AQP inhibitors (Yang, Kim et al. 2006, Yang, Zhang et al. 2008).

TGN-020 was shown in mouse models to significantly reduce AQP4-mediated edema following ischemia, but the molecule was administered before injury [16]. There was an approximately 10% reduction in brain volume [16]. Therapeutic administration must necessarily occur after a stroke, although a prophylactic treatment could be considered if the side effect profile of TGN-020 was acceptable. TGN-020 has since been tested on the same middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model and administered post-injury in mice. In a study using mouse models at a dose of 100 mg/kg, TGN-020 was administered 15 minutes post-ischemic injury and treated animals had better motor scores and less AQP4 expression around blood vessels when compared to untreated controls [34]. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC

TGN-020 was shown in mouse models to significantly reduce AQP4-mediated edema following ischemia, but the molecule was administered before injury (Igarashi, Huber et al. 2011). There was an approximately 10% reduction in brain volume (Igarashi, Huber et al. 2011). Therapeutic administration must necessarily occur after a stroke, although a prophylactic treatment could be considered if the side effect profile of TGN-020 was acceptable. TGN-020 has since been tested on the same middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model and administered post-injury in mice. In a study using mouse models at a dose of 100 mg/kg, TGN-020 was administered 15 minutes post-ischemic injury and treated animals had better motor scores and less AQP4 expression around blood vessels when compared to untreated controls (Pirici, Balsanu et al. 2017). The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC

50

) of TGN-020 was 3µM in

Xenopus oocytes expressing human AQP4, but there is no evidence to show that TGN-020 is AQP4-specific [35].

oocytes expressing human AQP4, but there is no evidence to show that TGN-020 is AQP4-specific (Huber, Tsujita et al. 2012).

Phloretin is a small molecule that acts as a non-specific aquaglyceroporin inhibitor. It has also been shown to inhibit the urea transporter, UT-A1, found in the kidney [36]. It has been speculated that the same mechanism underpinning urea inhibition is responsible for inhibition of the aquaglyceroporins, AQP3 and AQP9 [2][37]. Then 100 µM of phloretin was used to inhibit AQP9 expressed in

Phloretin is a small molecule that acts as a non-specific aquaglyceroporin inhibitor. It has also been shown to inhibit the urea transporter, UT-A1, found in the kidney (Esteva-Font, Phuan et al. 2013). It has been speculated that the same mechanism underpinning urea inhibition is responsible for inhibition of the aquaglyceroporins, AQP3 and AQP9 (Ishibashi, Sasaki et al. 1994, Tsukaguchi, Shayakul et al. 1998). Then 100 µM of phloretin was used to inhibit AQP9 expressed in

Xenopus oocytes, resulting in an 86% inhibition [2]. AQP3 glycerol permeability in proteoliposomes was inhibited by 500 µM phloretin, producing 83% inhibition. Phloretin had no effect on control proteoliposomes which had a P

oocytes, resulting in an 86% inhibition (Tsukaguchi, Shayakul et al. 1998). AQP3 glycerol permeability in proteoliposomes was inhibited by 500 µM phloretin, producing 83% inhibition. Phloretin had no effect on control proteoliposomes which had a P

gly

of ~2.8 × 10

−6 cm/s [3].

cm/s (Müller-Lucks, Gena et al. 2013).

A recent study identified new inhibitors of the aquaglyceroporins, AQP3 and AQP7. The compound DFP00173 was able to inhibit the glycerol permeability of human erythrocytes with an IC

50

of ~0.2µM. Compound Z433927330 reduced glycerol permeability with an IC

50

of ~0.6 µM. In a Chinese hamster ovary cell-line, compound DFP00173 was able to inhibit mouse AQP3 with an IC

50

of ~0.1µM and was selective for AQP3 over AQP7 and AQP9. Compound Z433927330 was able to inhibit mouse AQP7 in the same cell-line with an IC

50

of ~0.2 µM and with selectivity for AQP7 over AQP3 and AQP9; IC

50s for this compound for mouse AQP3 and AQP9 were ~0.7 µM and ~1.1 µM, respectively [18].

s for this compound for mouse AQP3 and AQP9 were ~0.7 µM and ~1.1 µM, respectively (Sonntag, Gena et al. 2019).

1.2. Heavy Metal Ion Inhibitors

2. Heavy Metal Ion Inhibitors

Heavy metal compounds have been used in cytotoxic treatments for many years, with the use of the platinum compound cisplatin being notable in cancer therapy. Many AQPs have been correlated with cancers, their presence influencing disease severity, increased local invasion, and the occurrence of metastasis [38]. AQP1 overexpression has been identified in brain, breast, lung, renal, cervical, ovarian, and colorectal cancers [39]. AQP3 overexpression has been found in skin, stomach, renal, liver, colorectal, lung, and cervical cancers [40]. AQP3 is highly expressed in skin carcinoma cells. The uptake of glycerol through AQP3 is thought to aid the growth of these cancer cells [38]. AQP4 overexpression is found in brain, lung, and thyroid cancers [41]. AQP5 overexpression has been found in breast, cervical, colorectal, liver, lung, pancreatic, ovarian, and esophageal cancers [42]. AQP7 and AQP8 overexpression are found in thyroid and cervical cancer, respectively [39]. AQP9 overexpression has been found in brain, liver, and ovarian cancers [43].

Heavy metal compounds have been used in cytotoxic treatments for many years, with the use of the platinum compound cisplatin being notable in cancer therapy. Many AQPs have been correlated with cancers, their presence influencing disease severity, increased local invasion, and the occurrence of metastasis (Nave, Castro et al. 2016). AQP1 overexpression has been identified in brain, breast, lung, renal, cervical, ovarian, and colorectal cancers (Dajani, Saripalli et al. 2018). AQP3 overexpression has been found in skin, stomach, renal, liver, colorectal, lung, and cervical cancers (Wang, Feng et al. 2015). AQP3 is highly expressed in skin carcinoma cells. The uptake of glycerol through AQP3 is thought to aid the growth of these cancer cells (Nave, Castro et al. 2016). AQP4 overexpression is found in brain, lung, and thyroid cancers (Papadopoulos and Saadoun 2015). AQP5 overexpression has been found in breast, cervical, colorectal, liver, lung, pancreatic, ovarian, and esophageal cancers (Aikman, de Almeida et al. 2018). AQP7 and AQP8 overexpression are found in thyroid and cervical cancer, respectively (Dajani, Saripalli et al. 2018). AQP9 overexpression has been found in brain, liver, and ovarian cancers (Aikman, de Almeida et al. 2018).

Nickel chloride has been shown to inhibit AQP3 overexpressed in human bronchial epithelium cells. Water permeability was reduced to approximately 60% in cells treated with 1 mM NiCl

2 compared to non-transfected control cells [10]. Mutational studies showed that the extracellular loop residues, Trp-128, Ser-152, and His-241, were all required for the observed inhibitory effect, but that further studies are required to confirm similar effects in other AQP3-expressing tissues such as the kidney [10]. Copper ions also inhibit AQP3 function and attempts to reduce the toxicity of copper compounds have been addressed by using nanoparticles for delivery [38]. Copper sulfate has been identified as an AQP3 inhibitor at 100 µM [9]. It is believed that copper ions act by binding the same three residues on the extracellular loops as nickel ions [44]. This inhibition mechanism is different from that of mercury ions, which bind to Cys-40 in AQP3 [44][45]. Copper compounds have been shown to specifically inhibit AQP3 and not AQP4, AQP5, or AQP1 [44], while other AQPs remain to be tested. Gold-based compounds have also been used as AQP3 inhibitors and have been shown to be effective. AQP3 is found in erythrocytes, alongside AQP1, however its role is mostly for glycerol rather than both water and glycerol permeability [6]. Erythrocytes showed a 90% decrease in glycerol permeability following treatment with 50 µM AuPhen. The binding of this gold compound is thought to be via Cys-40 and inhibition can be almost completely reversed by the addition of the reducing agent, 2-mercaptoethanol [6]. AuPhen and other Au(III) compounds such as Auterpy were also compared with copper and platinum compounds as AQP3 inhibitors [7][46]. Due to their effective inhibition of glycerol transport in AQP3, they were tested on AQP7, another aquaglyceroporin. Initial results have demonstrated that 15 µM AuPhen inhibited water and glycerol transport through AQP7 [7]: there was a reduction in water permeability (63%) as well as glycerol permeability (79%). Adipocytes overexpressing hAQP7 were used and permeability was measured using loading with 5 µM of calcein-AM and hyperosmotic shock. In silico docking studies suggest that Auphen binds AQP7 through an interaction with Met-47 [47]. Silver has also been used as a possible AQP inhibitor and is found to produce a rapid and irreversible inhibition of AQP1 in erythrocytes [48]. It has been shown to be a much more potent inhibitor of AQP1 in erythrocytes than mercury, [48]. Silver nitrate and silver sulfadiazine were tested as inhibitors to prevent shrinking of human erythrocytes in hyperosmotic solutions. A dose-response curve was used to calculate an IC

compared to non-transfected control cells (Zelenina, Bondar et al. 2003). Mutational studies showed that the extracellular loop residues, Trp-128, Ser-152, and His-241, were all required for the observed inhibitory effect, but that further studies are required to confirm similar effects in other AQP3-expressing tissues such as the kidney (Zelenina, Bondar et al. 2003). Copper ions also inhibit AQP3 function and attempts to reduce the toxicity of copper compounds have been addressed by using nanoparticles for delivery (Nave, Castro et al. 2016). Copper sulfate has been identified as an AQP3 inhibitor at 100 µM (Alejandra, Natalia et al. 2018). It is believed that copper ions act by binding the same three residues on the extracellular loops as nickel ions (Zelenina, Tritto et al. 2004). This inhibition mechanism is different from that of mercury ions, which bind to Cys-40 in AQP3 (Zelenina, Tritto et al. 2004, Spinello, de Almeida et al. 2016). Copper compounds have been shown to specifically inhibit AQP3 and not AQP4, AQP5, or AQP1 (Zelenina, Tritto et al. 2004), while other AQPs remain to be tested. Gold-based compounds have also been used as AQP3 inhibitors and have been shown to be effective. AQP3 is found in erythrocytes, alongside AQP1, however its role is mostly for glycerol rather than both water and glycerol permeability (Martins, Marrone et al. 2012). Erythrocytes showed a 90% decrease in glycerol permeability following treatment with 50 µM AuPhen. The binding of this gold compound is thought to be via Cys-40 and inhibition can be almost completely reversed by the addition of the reducing agent, 2-mercaptoethanol (Martins, Marrone et al. 2012). AuPhen and other Au(III) compounds such as Auterpy were also compared with copper and platinum compounds as AQP3 inhibitors (Martins, Ciancetta et al. 2013, de Almeida, Soveral et al. 2014). Due to their effective inhibition of glycerol transport in AQP3, they were tested on AQP7, another aquaglyceroporin. Initial results have demonstrated that 15 µM AuPhen inhibited water and glycerol transport through AQP7 (de Almeida, Soveral et al. 2014): there was a reduction in water permeability (63%) as well as glycerol permeability (79%). Adipocytes overexpressing hAQP7 were used and permeability was measured using loading with 5 µM of calcein-AM and hyperosmotic shock. In silico docking studies suggest that Auphen binds AQP7 through an interaction with Met-47 (Madeira, de Almeida et al. 2014). Silver has also been used as a possible AQP inhibitor and is found to produce a rapid and irreversible inhibition of AQP1 in erythrocytes (Niemietz and Tyerman 2002). It has been shown to be a much more potent inhibitor of AQP1 in erythrocytes than mercury, (Niemietz and Tyerman 2002). Silver nitrate and silver sulfadiazine were tested as inhibitors to prevent shrinking of human erythrocytes in hyperosmotic solutions. A dose-response curve was used to calculate an IC

50 of 3.9 µm and 1.24 µm and a 60% and 75% inhibition for silver nitrate and silver sulfadiazine, respectively. Gold and silver are thought to bind to sulfhydryl groups on cysteine residues of AQPs, but the complete mechanisms are not yet understood [6][7][48].

of 3.9 µm and 1.24 µm and a 60% and 75% inhibition for silver nitrate and silver sulfadiazine, respectively. Gold and silver are thought to bind to sulfhydryl groups on cysteine residues of AQPs, but the complete mechanisms are not yet understood (Niemietz and Tyerman 2002, Martins, Marrone et al. 2012, de Almeida, Soveral et al. 2014).

3. References

Aikman, B., A. de Almeida, S. M. Meier-Menches and A. Casini (2018). "Aquaporins in cancer development: opportunities for bioinorganic chemistry to contribute novel chemical probes and therapeutic agents." Metallomics 10(5): 696-712.

Alejandra, R., S. Natalia and D. Alicia E (2018). "The blocking of aquaporin-3 (AQP3) impairs extravillous trophoblast cell migration." Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 499(2): 227-232.

Brooks, H. L., J. W. Regan and A. J. Yool (2000). "Inhibition of Aquaporin-1 Water Permeability by Tetraethylammonium: Involvement of the Loop E Pore Region." Molecular Pharmacology 57(5): 1021-1026.

Castle, N. A. (2005). "Aquaporins as targets for drug discovery." Drug Discovery Today 10(7): 485-493.

Dajani, S., A. Saripalli and N. Sharma-Walia (2018). "Water transport proteins-aquaporins (AQPs) in cancer biology." Oncotarget 9(91): 36392-36405.

de Almeida, A., G. Soveral and A. Casini (2014). "Gold compounds as aquaporin inhibitors: new opportunities for therapy and imaging." MedChemComm 5(10): 1444-1453.

Detmers, F. J. M., B. L. de Groot, E. M. Müller, A. Hinton, I. B. M. Konings, M. Sze, S. L. Flitsch, H. Grubmüller and P. M. T. Deen (2006). "Quaternary Ammonium Compounds as Water Channel Blockers: SPECIFICITY, POTENCY, AND SITE OF ACTION." Journal of Biological Chemistry 281(20): 14207-14214.

Esteva-Font, C., P.-W. Phuan, Marc O. Anderson and A. S. Verkman (2013). "A Small Molecule Screen Identifies Selective Inhibitors of Urea Transporter UT-A." Chemistry & Biology 20(10): 1235-1244.

Gao, J., X. Wang, Y. Chang, J. Zhang, Q. Song, H. Yu and X. Li (2006). "Acetazolamide inhibits osmotic water permeability by interaction with aquaporin-1." Analytical Biochemistry 350(2): 165-170.

Huber, V. J., M. Tsujita, I. L. Kwee and T. Nakada (2009). "Inhibition of Aquaporin 4 by antiepileptic drugs." Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 17(1): 418-424.

Huber, V. J., M. Tsujita and T. Nakada (2012). "Aquaporins in drug discovery and pharmacotherapy." Molecular Aspects of Medicine 33(5): 691-703.

Huber, V. J., M. Tsujita, M. Yamazaki, K. Sakimura and T. Nakada (2007). "Identification of arylsulfonamides as Aquaporin 4 inhibitors." Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 17(5): 1270-1273.

Igarashi, H., V. J. Huber, M. Tsujita and T. Nakada (2011). "Pretreatment with a novel aquaporin 4 inhibitor, TGN-020, significantly reduces ischemic cerebral edema." Neurol Sci 32(1): 113-116.

Ishibashi, K., S. Sasaki, K. Fushimi, S. Uchida, M. Kuwahara, H. Saito, T. Furukawa, K. Nakajima, Y. Yamaguchi and T. Gojobori (1994). "Molecular cloning and expression of a member of the aquaporin family with permeability to glycerol and urea in addition to water expressed at the basolateral membrane of kidney collecting duct cells." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 91(14): 6269-6273.

Jeyaseelan, K., S. Sepramaniam, A. Armugam and E. M. Wintour (2006). "Aquaporins: a promising target for drug development." Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 10(6): 889-909.

Madeira, A., A. de Almeida, C. de Graaf, M. Camps, A. Zorzano, T. F. Moura, A. Casini and G. Soveral (2014). "A Gold Coordination Compound as a Chemical Probe to Unravel Aquaporin-7 Function." ChemBioChem 15(10): 1487-1494.

Martins, A. P., A. Ciancetta, A. de Almeida, A. Marrone, N. Re, G. Soveral and A. Casini (2013). "Aquaporin Inhibition by Gold(III) Compounds: New Insights." ChemMedChem 8(7): 1086-1092.

Martins, A. P., A. Marrone, A. Ciancetta, A. Galán Cobo, M. Echevarría, T. F. Moura, N. Re, A. Casini and G. Soveral (2012). "Targeting aquaporin function: potent inhibition of aquaglyceroporin-3 by a gold-based compound." PloS one 7(5): e37435-e37435.

Migliati, E., N. Meurice, P. DuBois, J. S. Fang, S. Somasekharan, E. Beckett, G. Flynn and A. J. Yool (2009). "Inhibition of aquaporin-1 and aquaporin-4 water permeability by a derivative of the loop diuretic bumetanide acting at an internal pore-occluding binding site." Molecular pharmacology 76(1): 105-112.

Müller-Lucks, A., P. Gena, D. Frascaria, N. Altamura, M. Svelto, E. Beitz and G. Calamita (2013). "Preparative scale production and functional reconstitution of a human aquaglyceroporin (AQP3) using a cell free expression system." New Biotechnology 30(5): 545-551.

Müller, E. M., J. S. Hub, H. Grubmüller and B. L. de Groot (2008). "Is TEA an inhibitor for human Aquaporin-1?" Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology 456(4): 663-669.

Nave, M., R. E. Castro, C. M. Rodrigues, A. Casini, G. Soveral and M. M. Gaspar (2016). "Nanoformulations of a potent copper-based aquaporin inhibitor with cytotoxic effect against cancer cells." Nanomedicine 11(14): 1817-1830.

Niemietz, C. M. and S. D. Tyerman (2002). "New potent inhibitors of aquaporins: silver and gold compounds inhibit aquaporins of plant and human origin." FEBS Letters 531(3): 443-447.

Ozu, M., R. A. Dorr, M. Teresa Politi, M. Parisi and R. Toriano (2011). "Water flux through human aquaporin 1: inhibition by intracellular furosemide and maximal response with high osmotic gradients." European Biophysics Journal 40(6): 737-746.

Papadopoulos, M. C. and S. Saadoun (2015). "Key roles of aquaporins in tumor biology." Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1848(10, Part B): 2576-2583.

Pastorekova, S., S. Parkkila, J. Pastorek and C. T. Supuran (2004). "Review Article." Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry 19(3): 199-229.

Pelletier, M. F. S. H., OH, US), Farr, George William (Rocky River, OH, US), Mcguirk, Paul Robert (Spring Hill, FL, US), Hall, Christopher H. (Shaker Heights, OH, US), Boron, Walter F. (Shaker Heights, OH, US) (2017). Methods of treating cerebral edema. United States, Aeromics, Inc. (Cleveland, OH, US).

Pirici, I., T. A. Balsanu, C. Bogdan, C. Margaritescu, T. Divan, V. Vitalie, L. Mogoanta, D. Pirici, R. O. Carare and D. F. Muresanu (2017). "Inhibition of Aquaporin-4 Improves the Outcome of Ischaemic Stroke and Modulates Brain Paravascular Drainage Pathways." International journal of molecular sciences 19(1): 46.

Preston, G. M., T. P. Carroll, W. B. Guggino and P. Agre (1992). "Appearance of water channels in Xenopus oocytes expressing red cell CHIP28 protein." Science 256.

Preston, G. M., J. S. Jung, W. B. Guggino and P. Agre (1993). "The mercury-sensitive residue at cysteine 189 in the CHIP28 water channel." J Biol Chem 268(1): 17-20.

Shank, R. P. and B. E. Maryanoff (2008). "Molecular Pharmacodynamics, Clinical Therapeutics, and Pharmacokinetics of Topiramate." CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics 14(2): 120-142.

Søgaard, R. and T. Zeuthen (2008). "Test of blockers of AQP1 water permeability by a high-resolution method: no effects of tetraethylammonium ions or acetazolamide." Pflügers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology 456(2): 285-292.

Sonntag, Y., P. Gena, A. Maggio, T. Singh, I. Artner, M. K. Oklinski, U. Johanson, P. Kjellbom, J. D. Nieland, S. Nielsen, G. Calamita and M. Rutzler (2019). "Identification and characterization of potent and selective aquaporin-3 and aquaporin-7 inhibitors." J Biol Chem.

Spinello, A., A. de Almeida, A. Casini and G. Barone (2016). "The inhibition of glycerol permeation through aquaglyceroporin-3 induced by mercury(II): A molecular dynamics study." Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry 160: 78-84.

Tang, G. and G.-Y. Yang (2016). "Aquaporin-4: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Cerebral Edema." International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17(10): 1413.

Tanimura, Y., Y. Hiroaki and Y. Fujiyoshi (2009). "Acetazolamide reversibly inhibits water conduction by aquaporin-4." Journal of Structural Biology 166(1): 16-21.

Tsukaguchi, H., C. Shayakul, U. V. Berger, B. Mackenzie, S. Devidas, W. B. Guggino, A. N. van Hoek and M. A. Hediger (1998). "Molecular Characterization of a Broad Selectivity Neutral Solute Channel." Journal of Biological Chemistry 273(38): 24737-24743.

Tsutomu Nakada, V. H. (2010). Inhibitors of Aquaporin 4, Methods and uses thereof. N. University. Japan.

Verkman, A. S., M. O. Anderson and M. C. Papadopoulos (2014). "Aquaporins: important but elusive drug targets." Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 13: 259.

Wang, J., L. Feng, Z. Zhu, M. Zheng, D. Wang, Z. Chen and H. Sun (2015). "Aquaporins as diagnostic and therapeutic targets in cancer: How far we are?" Journal of Translational Medicine 13(1): 96.

Yang, B., J. K. Kim and A. S. Verkman (2006). "Comparative efficacy of HgCl2 with candidate aquaporin-1 inhibitors DMSO, gold, TEA+ and acetazolamide." FEBS Letters 580(28-29): 6679-6684.

Yang, B., H. Zhang and A. S. Verkman (2008). "Lack of aquaporin-4 water transport inhibition by antiepileptics and arylsulfonamides." Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry 16(15): 7489-7493.

Zelenina, M., A. A. Bondar, S. Zelenin and A. Aperia (2003). "Nickel and Extracellular Acidification Inhibit the Water Permeability of Human Aquaporin-3 in Lung Epithelial Cells." Journal of Biological Chemistry 278(32): 30037-30043.

Zelenina, M., S. Tritto, A. A. Bondar, S. Zelenin and A. Aperia (2004). "Copper Inhibits the Water and Glycerol Permeability of Aquaporin-3." Journal of Biological Chemistry 279(50): 51939-51943.