Ocular drug administration encompasses a range of routes, each with its own advantages and limitations. The available methods include systemic delivery (such as oral, intravenous, and subcutaneous routes) as well as local delivery options (including topical eye drops, periocular or intravitreal injections, and intravitreal implants). While these approaches can be effective in delivering medications to the eye, they also have inherent drawbacks, which will be explored in greater detail in this entry. Notably, understanding the strengths and limitations of these ocular drug administration routes is crucial for optimizing therapy and achieving the desired therapeutic outcomes while minimizing potential adverse effects.

- Ocular drug administration

- Systemic delivery

- Topical eye drops

- Periocular injections

- Intravitreal injections

- Therapeutic goals

- Ophthalmology

1. Route of Administration

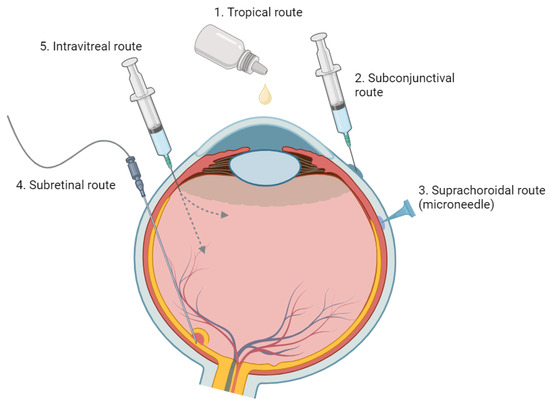

Various routes exist for ocular medication administration, each with distinct pros and cons. Systemic delivery (oral, intravenous, subcutaneous) and local methods (topical drops, periocular/IV injections, IV implants) are commonly used [20][1]. However, these methods have limitations. Table 1 and Figure 1 provide an overview of the advantages and disadvantages of different ocular drug administration approaches [2,21][2][3].

Figure 1. An Overview of Various Ophthalmic Medication Delivery Routes. This figure illustrates the range of administration methods used in ophthalmic medicine, including topical, subconjunctival, intravitreal, suprachoroidal, and subretinal techniques.

| Injection Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Topical Eye Drops [22][4] | Prevalent, well-known method | Low bioavailability to posterior segment tissues |

| Non-invasive method for ocular drug delivery | Short duration of action, requiring frequent administration | |

| Relies on patient’s compliance | ||

| Local complications (ocular surface irritation, cataracts, ocular hypertension, periocular aesthetic issues) | ||

| Systemic Drug Administration | Noninvasive and potentially patient-preferred | High doses often required due to reduced accessibility to targeted ocular tissues |

| Usable as standalone or in combination with topical delivery | Potential systemic side effects due to high dosage, necessitating safety and toxicity considerations | |

| Effective bioavailability is challenging due to blood–ocular barriers | ||

| Intravitreal Injection [23][5] | Office-based, outpatient procedure | Requires frequent in-office visits |

| High bioavailability (bypass corneal and blood–retinal barriers) | Potential for severe complications (Endophthalmitis, retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage) | |

| Fewer systemic side effects compared to oral or IV administration | Local complications (increased IOP, cataract formation) | |

| Rapid therapeutic onset | Possible post-injection floaters | |

| Systemic absorption and side effects can still occur | ||

| Subretinal Injection [24][6] | Targeted treatment for the RPE and outer retina | Invasive procedure, requires vitrectomy |

| Reduced immune reactions for gene therapy using viral vectors (due to injection in an immune-privileged site) |

Limited distribution of injectate within subretinal space; effects confined to injection site |

1.1. Topical Administration

Topical administration, primarily through eye drops, is a commonly used non-invasive approach for ocular drug delivery. However, it presents challenges due to the eye's anatomy and physiology.

The concentration gradient from the tear reservoir to the cornea or conjunctiva drives passive absorption, but only a small fraction of the administered drop (approximately 20%) is retained in the eye [25][7]. Within a few minutes, about half of the medication leaves the eye, with a rapid turnover rate of around 15% per minute. Factors like reflex tearing, consecutive dosing, and the small cul-de-sac of the eye contribute to fast tear turnover, accelerating drug clearance and hindering effective absorption [2,21][2][3].

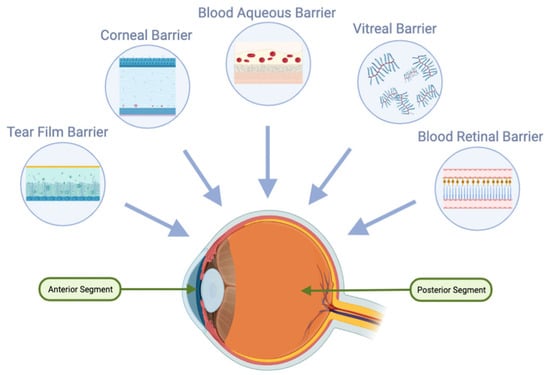

Furthermore, drugs must traverse the hydrophobic tight junctions formed by the epithelium and endothelium, as well as the hydrophilic stroma layer of the cornea (Figure 3) [26][8]. The low permeability of the cornea and sclera limits drug penetration, reducing the bioavailability of topically administered drugs.

Due to the barriers posed by the cornea and high tear turnover rates, frequent and high-dose applications are often required for topical administration. This can lead to local and systemic side effects, potentially compromising patient compliance [27][9]. Studies have shown that medication non-compliance rates in the general population are approximately 80% [28][10], and these challenges are even more pronounced in certain populations, such as the elderly and individuals with physical disabilities.

Additionally, topical drugs may affect unaffected tissue, resulting in side effects. For example, chronic use of topical steroids can lead to complications like cataracts and ocular hypertension [22][4]. Similarly, topical prostaglandins can cause undesirable periocular aesthetic concerns [29][11].

Although topical application is a primary method of ocular drug delivery, these complexities underscore the need for advancements in drug delivery methods to overcome the limitations associated with topical administration.

1.2. Systemic Administration

Oral delivery has been investigated as a potential route for ocular drug administration, either alone or in combination with topical delivery [30,31,32,33][12][13][14][15]. While it offers a non-invasive option for managing chronic retinal diseases, oral administration has limitations. It has reduced accessibility to targeted ocular tissues, requiring high doses for therapeutic effectiveness. However, high dosages can lead to systemic side effects, necessitating careful consideration of safety and toxicity [34,35][16][17].

For oral delivery to be effective in ocular applications, achieving high oral bioavailability is crucial. Additionally, after oral absorption, molecules must traverse systemic circulation and overcome the blood-ocular barriers, including the blood-aqueous and blood-retinal barriers (Figure 2). The blood-retinal barrier consists of an inner barrier, protected by the fenestrated endothelium of retinal vasculature, and an outer barrier, maintained by tight junctions within the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). These protective ocular structures present significant challenges for systemic drug administration [34,35][16][17].

Systemic medications, including steroidal and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, as well as immunomodulatory agents (both biologic and nonbiologic), are effective for treating uveitic macular edema (UME). However, they are typically reserved for bilateral disease or cases unresponsive to local therapy due to potential adverse effects (AEs) such as infections and gastrointestinal (GI) disturbances [20,36,37][1][18][19]. Additionally, the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and systemic immunomodulatory agents, either alone or in combination with steroids, may further increase the risk of GI disturbances [20,36,37][1][18][19].

1.3. Periocular Injection

Periocular drug administration offers an alternative to topical and systemic dosing, which struggle to achieve therapeutic drug concentrations in the posterior segment [2]. Compared to intravenous administration, periocular routes (subconjunctival, subtenon, retrobulbar, and peribulbar) are less invasive [2].

Subconjunctival injections can enhance absorption of water-soluble drugs by bypassing the conjunctival epithelial barrier. However, access to the posterior eye segment remains limited due to various barriers, including dynamic factors such as conjunctival blood and lymphatic circulation [38,39,40][20][21][22]. These dynamic barriers contribute to rapid drug elimination, reducing ocular bioavailability and vitreous drug levels after administration [38,39,40][20][21][22]. Although some molecules can reach the neural retina and photoreceptor cells through the permeable sclera [20[1][23],41], the high blood flow in the choroid can remove a significant portion of the drug before it reaches its target. Moreover, the presence of tight junctions within the retinal pigment epithelium forms blood-retinal barriers that restrict drug availability to the photoreceptor cells.

1.4. Intravitreal Injection

IV administration is widely used as a first-line therapy for various ocular conditions, including neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD), diabetic macular edema (DME), and macular edema secondary to retinal vein occlusion (RVO) [42][43][44][24][25][26]. It offers advantages such as direct drug delivery to the retina and vitreous, bypassing corneal and scleral barriers, and circumventing the blood-retinal barrier. These benefits ensure high bioavailability, rapid therapeutic effects, and improved patient compliance compared to topical eyedrops [45][27].

However, IV injections have drawbacks and potential complications. Severe complications include the risk of endophthalmitis, retinal detachment, and vitreous hemorrhage. IV steroids specifically can cause increased intraocular pressure and cataract development [43][25]. Minor side effects, such as floaters, and the potential for systemic absorption and associated side effects can also impact patient satisfaction and treatment adherence [43][25].

Another challenge with IV administration is the need for frequent injections due to the short half-life of drugs [46][47][48][28][29][30]. After injection, drugs are eliminated either anteriorly or posteriorly. Anterior elimination involves diffusion through the vitreous, aqueous turnover, and uveal blood flow. Posterior elimination requires permeation through the blood-retinal barrier, which can be passive or actively mediated. Hydrophilic drugs with larger molecular weights have longer half-lives, while hydrophobic drugs with smaller molecular weights have shorter half-lives, necessitating more frequent injections. The burden of regular in-office visits and patient-specific factors like age and prior vitrectomy can further complicate the treatment regimen and decrease compliance [48][49][30][31].

To overcome the limitations of short treatment duration and frequent in-office visits, intraocular implants have been developed. The Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment (MUST) trial assessed a fluocinolone acetonide (FA) intraocular implant that releases the drug over approximately 30 months [50][32]. In the short term, the FA implant demonstrated superior efficacy in controlling uveitic inflammation and reducing macular edema compared to systemic corticosteroids, but the differences diminished after 24 months. However, the FA implant was associated with a fourfold increase in the risk of elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) requiring intervention. Extended follow-up after seven years revealed that patients receiving systemic therapy had better visual acuity than those with IV FA implants [51][33].

In the realm of gene therapy, intravitreal injection of an anti-VEGF transgene product (Adverum Biotechnologies) has shown promise but raises concerns about significant inflammatory responses [52][53][54][55][34][35][36][37]. The vitreous presents challenges for retinal gene delivery due to components like hyaluronan, which can lead to aggregation and immobilization of DNA/liposome complexes [56][57][38][39]. The inner limiting membrane (ILM) and the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) also act as barriers to retinal gene delivery and drug transport to the choroid, respectively [58][9][40][41].

Emerging alternatives like subretinal and subconjunctival (SC) drug delivery hold potential for longer-lasting effects, reducing injection frequency, and minimizing gene therapy-induced inflammation [59][42].

1.5. Subretinal Injection

Subretinal delivery is a promising approach for retinal gene therapy, particularly for retinal degeneration and vascular diseases. This method involves directly introducing viral vectors into the immune-privileged subretinal space, allowing targeted treatment for the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and outer retina while minimizing immune reactions [24][6].

The FDA-approved gene therapy Voretigene neparvovec-rzyl (Luxturna) for RPE65-associated inherited retinal dystrophy has shown promising outcomes [60][61][43][44]. Gene therapy also holds potential for conditions like diabetic retinopathy (DR) and age-related macular degeneration (AMD), suggesting the possibility of a single-dose treatment for these chronic diseases. Early studies using subretinal adenoviral vector anti-VEGF gene therapy have demonstrated a significant reduction in treatment burden and a favorable safety profile for neovascular AMD [62][45].

However, it's important to acknowledge that subretinal delivery presents its own challenges. It requires an invasive vitrectomy procedure for administration, and the localized distribution of the injected material may limit therapeutic effects to the vicinity of the injection site [59].[142].

References

- Wu, K.Y.; Joly-Chevrier, M.; Akbar, D.; Tran, S.D. Overcoming Treatment Challenges in Posterior Segment Diseases with Biodegradable Nano-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Ghate, D.; Edelhauser, H.F. Ocular Drug Delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2006, 3, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Patel, S.R.; Lin, A.S.P.; Edelhauser, H.F.; Prausnitz, M.R. Suprachoroidal Drug Delivery to the Back of the Eye Using Hollow Microneedles. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Lampen, S.I.R.; Khurana, R.N.; Noronha, G.; Brown, D.M.; Wykoff, C.C. Suprachoroidal Space Alterations Following Delivery of Triamcinolone Acetonide: Post-Hoc Analysis of the Phase 1/2 HULK Study of Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retina 2018, 49, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Bhattacharyya, S.; Hariprasad, S.M.; Albini, T.A.; Dutta, S.K.; John, D.; Padula, W.V.; Harrison, D.; Joseph, G. Suprachoroidal Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide Injectable Suspension for the Treatment of Macular Edema Associated with Uveitis in the United States: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Value Health 2022, 25, 1705–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Dubashynskaya, N.; Poshina, D.; Raik, S.; Urtti, A.; Skorik, Y.A. Polysaccharides in Ocular Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2019, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Naftali Ben Haim, L.; Moisseiev, E. Drug Delivery via the Suprachoroidal Space for the Treatment of Retinal Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Margolis, R.; Spaide, R.F. A Pilot Study of Enhanced Depth Imaging Optical Coherence Tomography of the Choroid in Normal Eyes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 147, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Mahabadi, N.; Al Khalili, Y. Neuroanatomy, Retina. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]Kaplan, H.J. Anatomy and Function of the Eye. In Chemical Immunology and Allergy; Niederkorn, J.Y., Kaplan, H.J., Eds.; KARGER: Basel, Switzerland, 2007; pp. 4–10. ISBN 978-3-8055-8187-5. [Google Scholar]Vurgese, S.; Panda-Jonas, S.; Jonas, J.B. Scleral Thickness in Human Eyes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Patel, S.R.; Berezovsky, D.E.; McCarey, B.E.; Zarnitsyn, V.; Edelhauser, H.F.; Prausnitz, M.R. Targeted Administration into the Suprachoroidal Space Using a Microneedle for Drug Delivery to the Posterior Segment of the Eye. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 4433–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Ciulla, T.; Yeh, S. Microinjection via the Suprachoroidal Space: A Review of a Novel Mode of Administration. Am. J. Manag. Care 2022, 28, S243–S252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Meng, W.; Butterworth, J.; Malecaze, F.; Calvas, P. Axial Length of Myopia: A Review of Current Research. Ophthalmologica 2011, 225, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Del Amo, E.M.; Rimpelä, A.-K.; Heikkinen, E.; Kari, O.K.; Ramsay, E.; Lajunen, T.; Schmitt, M.; Pelkonen, L.; Bhattacharya, M.; Richardson, D.; et al. Pharmacokinetic Aspects of Retinal Drug Delivery. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2017, 57, 134–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Emi, K.; Pederson, J.E.; Toris, C.B. Hydrostatic Pressure of the Suprachoroidal Space. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1989, 30, 233–238. [Google Scholar]Krohn, J.; Bertelsen, T. Light Microscopy of Uveoscleral Drainage Routes after Gelatine Injections into the Suprachoroidal Space. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 1998, 76, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Krohn, J.; Bertelsen, T. Corrosion Casts of the Suprachoroidal Space and Uveoscleral Drainage Routes in the Human Eye. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 1997, 75, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Chiang, B.; Kim, Y.C.; Edelhauser, H.F.; Prausnitz, M.R. Circumferential Flow of Particles in the Suprachoroidal Space Is Impeded by the Posterior Ciliary Arteries. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 145, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Urtti, A. Challenges and Obstacles of Ocular Pharmacokinetics and Drug Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006, 58, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Wu, K.Y.; Ashkar, S.; Jain, S.; Marchand, M.; Tran, S.D. Breaking Barriers in Eye Treatment: Polymeric Nano-Based Drug-Delivery System for Anterior Segment Diseases and Glaucoma. Polymers 2023, 15, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Carnahan, M.C.; Goldstein, D.A. Ocular Complications of Topical, Peri-Ocular, and Systemic Corticosteroids. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2000, 11, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Tyagi, P.; Kadam, R.S.; Kompella, U.B. Comparison of Suprachoroidal Drug Delivery with Subconjunctival and Intravitreal Routes Using Noninvasive Fluorophotometry. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Yiu, G.; Chung, S.H.; Mollhoff, I.N.; Nguyen, U.T.; Thomasy, S.M.; Yoo, J.; Taraborelli, D.; Noronha, G. Suprachoroidal and Subretinal Injections of AAV Using Transscleral Microneedles for Retinal Gene Delivery in Nonhuman Primates. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 16, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Agrahari, V.; Mandal, A.; Agrahari, V.; Trinh, H.M.; Joseph, M.; Ray, A.; Hadji, H.; Mitra, R.; Pal, D.; Mitra, A.K. A Comprehensive insight on ocular pharmacokinetics. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2016, 6, 735–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Loftsson, T.; Stefánsson, E. Aqueous Eye Drops Containing Drug/Cyclodextrin Nanoparticles Deliver Therapeutic Drug Concentrations to Both Anterior and Posterior Segment. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022, 100, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Uchino, M.; Yokoi, N.; Shimazaki, J.; Hori, Y.; Tsubota, K.; on behalf of the Japan Dry Eye Society. Adherence to Eye Drops Usage in Dry Eye Patients and Reasons for Non-Compliance: A Web-Based Survey. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Foley, L.; Larkin, J.; Lombard-Vance, R.; Murphy, A.W.; Hynes, L.; Galvin, E.; Molloy, G.J. Prevalence and Predictors of Medication Non-Adherence among People Living with Multimorbidity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Holló, G. The Side Effects of the Prostaglandin Analogues. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2007, 6, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Santulli, R.J.; Kinney, W.A.; Ghosh, S.; Decorte, B.L.; Liu, L.; Tuman, R.W.A.; Zhou, Z.; Huebert, N.; Bursell, S.E.; Clermont, A.C.; et al. Studies with an Orally Bioavailable Alpha V Integrin Antagonist in Animal Models of Ocular Vasculopathy: Retinal Neovascularization in Mice and Retinal Vascular Permeability in Diabetic Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 324, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Shirasaki, Y.; Miyashita, H.; Yamaguchi, M. Exploration of Orally Available Calpain Inhibitors. Part 3: Dipeptidyl Alpha-Ketoamide Derivatives Containing Pyridine Moiety. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 5691–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Kampougeris, G.; Antoniadou, A.; Kavouklis, E.; Chryssouli, Z.; Giamarellou, H. Penetration of Moxifloxacin into the Human Aqueous Humour after Oral Administration. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 89, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Sakamoto, H.; Sakamoto, M.; Hata, Y.; Kubota, T.; Ishibashi, T. Aqueous and Vitreous Penetration of Levofloxacin after Topical and/or Oral Administration. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 17, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Shirasaki, Y. Molecular Design for Enhancement of Ocular Penetration. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 2462–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Kaur, I.P.; Smitha, R.; Aggarwal, D.; Kapil, M. Acetazolamide: Future Perspective in Topical Glaucoma Therapeutics. Int. J. Pharm. 2002, 248, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Gipson, I.K.; Argüeso, P. Role of Mucins in the Function of the Corneal and Conjunctival Epithelia. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2003, 231, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Geroski, D.H.; Edelhauser, H.F. Transscleral Drug Delivery for Posterior Segment Disease. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 52, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Hosseini, K.; Matsushima, D.; Johnson, J.; Widera, G.; Nyam, K.; Kim, L.; Xu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Cormier, M. Pharmacokinetic Study of Dexamethasone Disodium Phosphate Using Intravitreal, Subconjunctival, and Intravenous Delivery Routes in Rabbits. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 24, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Weijtens, O.; Feron, E.J.; Schoemaker, R.C.; Cohen, A.F.; Lentjes, E.G.; Romijn, F.P.; van Meurs, J.C. High Concentration of Dexamethasone in Aqueous and Vitreous after Subconjunctival Injection. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1999, 128, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Kim, S.H.; Csaky, K.G.; Wang, N.S.; Lutz, R.J. Drug Elimination Kinetics Following Subconjunctival Injection Using Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Prausnitz, M.R.; Noonan, J.S. Permeability of Cornea, Sclera, and Conjunctiva: A Literature Analysis for Drug Delivery to the Eye. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998, 87, 1479–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Modi, Y.S.; Tanchon, C.; Ehlers, J.P. Comparative Safety and Tolerability of Anti-VEGF Therapy in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Drug Saf. 2015, 38, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Massa, H.; Nagar, A.M.; Vergados, A.; Dadoukis, P.; Patra, S.; Panos, G.D. Intravitreal Fluocinolone Acetonide Implant (ILUVIEN®) for Diabetic Macular Oedema: A Literature Review. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Adelman, R.A.; Parnes, A.J.; Bopp, S.; Saad Othman, I.; Ducournau, D. Strategy for the Management of Macular Edema in Retinal Vein Occlusion: The European VitreoRetinal Society Macular Edema Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 870987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Gao, L.; Zhao, X.; Jiao, L.; Tang, L. Intravitreal Corticosteroids for Diabetic Macular Edema: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eye Vis. 2021, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Hussain, R.M.; Hariprasad, S.M.; Ciulla, T.A. Treatment Burden in Neovascular AMD:Visual Acuity Outcomes Are Associated with Anti-VEGF Injection Frequency. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retina 2017, 48, 780–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Ciulla, T.A.; Bracha, P.; Pollack, J.; Williams, D.F. Real-World Outcomes of Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapy in Diabetic Macular Edema in the United States. Ophthalmol. Retina 2018, 2, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Ciulla, T.; Pollack, J.S.; Williams, D.F. Visual Acuity Outcomes and Anti-VEGF Therapy Intensity in Macular Oedema Due to Retinal Vein Occlusion: A Real-World Analysis of 15 613 Patient Eyes. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 105, 1696–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Chin, H.-S.; Park, T.-S.; Moon, Y.-S.; Oh, J.-H. Difference in clearance of intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide between vitrectomized and nonvitrectomized eyes. Retina 2005, 25, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment Trial Research Group. The Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment (MUST) Trial: Rationale, Design and Baseline Characteristics. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 149, 550–561.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Writing Committee for the Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment (MUST) Trial and Follow-up Study Research Group. Association between Long-Lasting Intravitreous Fluocinolone Acetonide Implant vs. Systemic Anti-Inflammatory Therapy and Visual Acuity at 7 Years Among Patients with Intermediate, Posterior, or Panuveitis. JAMA 2017, 317, 1993–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Holekamp, N.M.; Campochiaro, P.A.; Chang, M.A.; Miller, D.; Pieramici, D.; Adamis, A.P.; Brittain, C.; Evans, E.; Kaufman, D.; Maass, K.F.; et al. Archway Randomized Phase 3 Trial of the Port Delivery System with Ranibizumab for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Heier, J.S.; Khanani, A.M.; Quezada Ruiz, C.; Basu, K.; Ferrone, P.J.; Brittain, C.; Figueroa, M.S.; Lin, H.; Holz, F.G.; Patel, V.; et al. Efficacy, Durability, and Safety of Intravitreal Faricimab up to Every 16 Weeks for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (TENAYA and LUCERNE): Two Randomised, Double-Masked, Phase 3, Non-Inferiority Trials. Lancet 2022, 399, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Genentech: Press Releases|Friday, 28 January 2022. Available online: https://www.gene.com/media/press-releases/14943/2022-01-28/fda-approves-genentechs-vabysmo-the-firs (accessed on 6 July 2023).Genentech: Press Releases|Friday, 22 October 2021. Available online: https://www.gene.com/media/press-releases/14935/2021-10-22/fda-approves-genentechs-susvimo-a-first- (accessed on 6 July 2023).Pitkänen, L.; Ruponen, M.; Nieminen, J.; Urtti, A. Vitreous Is a Barrier in Nonviral Gene Transfer by Cationic Lipids and Polymers. Pharm. Res. 2003, 20, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Peeters, L.; Sanders, N.N.; Braeckmans, K.; Boussery, K.; Van de Voorde, J.; De Smedt, S.C.; Demeester, J. Vitreous: A Barrier to Nonviral Ocular Gene Therapy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005, 46, 3553–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Dalkara, D.; Kolstad, K.D.; Caporale, N.; Visel, M.; Klimczak, R.R.; Schaffer, D.V.; Flannery, J.G. Inner Limiting Membrane Barriers to AAV-Mediated Retinal Transduction from the Vitreous. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2009, 17, 2096–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Kansara, V.; Muya, L.; Wan, C.-R.; Ciulla, T.A. Suprachoroidal Delivery of Viral and Nonviral Gene Therapy for Retinal Diseases. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 36, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Russell, S.; Bennett, J.; Wellman, J.A.; Chung, D.C.; Yu, Z.-F.; Tillman, A.; Wittes, J.; Pappas, J.; Elci, O.; McCague, S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Voretigene Neparvovec (AAV2-HRPE65v2) in Patients with RPE65-Mediated Inherited Retinal Dystrophy: A Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Maguire, A.M.; Russell, S.; Chung, D.C.; Yu, Z.-F.; Tillman, A.; Drack, A.V.; Simonelli, F.; Leroy, B.P.; Reape, K.Z.; High, K.A.; et al. Durability of Voretigene Neparvovec for Biallelic RPE65-Mediated Inherited Retinal Disease: Phase 3 Results at 3 and 4 Years. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]REGENXBIO Announces Additional Positive Interim Phase I/IIa and Long-Term Follow-Up Data of RGX-314 for the Treatment of Wet AMD|Regenxbio Inc. Available online: https://ir.regenxbio.com/news-releases/news-release-details/regenxbio-announces-additional-positive-interim-phase-iiia-and/ (accessed on 6 July 2023).Jung, J.H.; Chae, J.J.; Prausnitz, M.R. Targeting Drug Delivery within the Suprachoroidal Space. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 1654–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Hancock, S.E.; Wan, C.-R.; Fisher, N.E.; Andino, R.V.; Ciulla, T.A. Biomechanics of Suprachoroidal Drug Delivery: From Benchtop to Clinical Investigation in Ocular Therapies. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2021, 18, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Peden, M.C.; Min, J.; Meyers, C.; Lukowski, Z.; Li, Q.; Boye, S.L.; Levine, M.; Hauswirth, W.W.; Ratnakaram, R.; Dawson, W.; et al. Ab-Externo AAV-Mediated Gene Delivery to the Suprachoroidal Space Using a 250 Micron Flexible Microcatheter. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Tyagi, P.; Barros, M.; Stansbury, J.W.; Kompella, U.B. Light Activated, In Situ Forming Gel for Sustained Suprachoroidal Delivery of Bevacizumab. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 2858–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Chen, M.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Han, Y.; Cheng, L. Safety and Pharmacodynamics of Suprachoroidal Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide as a Controlled Ocular Drug Release Model. J. Control. Release 2015, 203, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Kansara, V.S.; Hancock, S.E.; Muya, L.W.; Ciulla, T.A. Suprachoroidal Delivery Enables Targeting, Localization and Durability of Small Molecule Suspensions. J. Control. Release 2022, 349, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Yeh, S.; Ciulla, T. Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide Injectable Suspension for Macular Edema Associated with Noninfectious Uveitis: An In-Depth Look at Efficacy and Safety. Am. J. Manag. Care 2023, 29, S19–S28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]Fisher, N.; Yoo, J.; Hancock, S.E.; Andino, R.V. A Novel Technique to Characterize Key Fluid Mechanic Properties of the SC Injection Procedure in an In Vivo Model; Clear Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Annual Meeting: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]Fisher, N.; Wan, C. Suprachoroidal Delivery with the SCS Microinjector™: Characterization of Operational Forces. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 24. [Google Scholar]Moisseiev, E.; Loewenstein, A.; Yiu, G. The Suprachoroidal Space: From Potential Space to a Space with Potential. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2016, 10, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Gu, B.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Ma, Q.; Shen, M.; Cheng, L. Real-Time Monitoring of Suprachoroidal Space (SCS) Following SCS Injection Using Ultra-High Resolution Optical Coherence Tomography in Guinea Pig Eyes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 3623–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Savinainen, A.; Grossniklaus, H.; Kang, S.; Rasmussen, C.; Bentley, E.; Krakova, Y.; Struble, C.B.; Rich, C. Ocular Distribution and Efficacy after Suprachoroidal Injection of AU-011 for Treatment of Ocular Melanoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 3615. [Google Scholar]Chiang, B.; Venugopal, N.; Grossniklaus, H.E.; Jung, J.H.; Edelhauser, H.F.; Prausnitz, M.R. Thickness and Closure Kinetics of the Suprachoroidal Space Following Microneedle Injection of Liquid Formulations. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Jung, J.H.; Park, S.; Chae, J.J.; Prausnitz, M.R. Collagenase Injection into the Suprachoroidal Space of the Eye to Expand Drug Delivery Coverage and Increase Posterior Drug Targeting. Exp. Eye Res. 2019, 189, 107824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Nork, T.M.; Katz, A.W.; Kim, C.B.Y.; Rasmussen, C.A.; Wabers, H.D.; Bentley, E.; Struble, C.B.; Savinainen, A. Distribution of Aqueous Solutions Injected Suprachoroidally (SC) in Rabbits. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 320. [Google Scholar]Oshika, T.; Bissen-Miyajima, H.; Fujita, Y.; Hayashi, K.; Mano, T.; Miyata, K.; Sugita, T.; Taira, Y. Prospective Randomized Comparison of DisCoVisc and Healon5 in Phacoemulsification and Intraocular Lens Implantation. Eye 2010, 24, 1376–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Kim, Y.C.; Oh, K.H.; Edelhauser, H.F.; Prausnitz, M.R. Formulation to Target Delivery to the Ciliary Body and Choroid via the Suprachoroidal Space of the Eye Using Microneedles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 95, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Jung, J.H.; Kim, S.S.; Chung, H.; Hejri, A.; Prausnitz, M.R. Six-Month Sustained Delivery of Anti-VEGF from in-Situ Forming Hydrogel in the Suprachoroidal Space. J. Control. Release 2022, 352, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Chiang, B.; Wang, K.; Ethier, C.R.; Prausnitz, M.R. Clearance Kinetics and Clearance Routes of Molecules From the Suprachoroidal Space After Microneedle Injection. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Mustafa, M.B.; Tipton, D.L.; Barkley, M.D.; Russo, P.S.; Blum, F.D. Dye Diffusion in Isotropic and Liquid-Crystalline Aqueous (Hydroxypropyl)Cellulose. Macromolecules 1993, 26, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]FITC-Dextran Fluorescein Isothiocyanate Dextran. 2011. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/FITC-Dextran-Fluorescein-isothiocyanate-dextran/01c8e9539524bc604f6b45a6bbb06dd03507d82f (accessed on 30 May 2023).Hackett, S.F.; Fu, J.; Kim, Y.C.; Tsujinaka, H.; Shen, J.; Lima E Silva, R.; Khan, M.; Hafiz, Z.; Wang, T.; Shin, M.; et al. Sustained Delivery of Acriflavine from the Suprachoroidal Space Provides Long Term Suppression of Choroidal Neovascularization. Biomaterials 2020, 243, 119935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Edwards, A.; Prausnitz, M.R. Fiber Matrix Model of Sclera and Corneal Stroma for Drug Delivery to the Eye. AIChE J. 1998, 44, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Jung, J.H.; Desit, P.; Prausnitz, M.R. Targeted Drug Delivery in the Suprachoroidal Space by Swollen Hydrogel Pushing. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 2069–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Jung, J.H.; Chiang, B.; Grossniklaus, H.E.; Prausnitz, M.R. Ocular Drug Delivery Targeted by Iontophoresis in the Suprachoroidal Space Using a Microneedle. J. Control. Release 2018, 277, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Touchard, E.; Berdugo, M.; Bigey, P.; El Sanharawi, M.; Savoldelli, M.; Naud, M.-C.; Jeanny, J.-C.; Behar-Cohen, F. Suprachoroidal Electrotransfer: A Nonviral Gene Delivery Method to Transfect the Choroid and the Retina without Detaching the Retina. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2012, 20, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Edelhauser, H.F.; Verhoeven, R.S.; Burke, B.; Struble, C.B.; Patel, S.R. Intraocular Distribution and Targeting of Triamcinolone Acetonide Suspension Administered Into the Suprachoroidal Space. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 5259. [Google Scholar]Muya, L.; Kansara, V.; Cavet, M.E.; Ciulla, T. Suprachoroidal Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide Suspension: Ocular Pharmacokinetics and Distribution in Rabbits Demonstrates High and Durable Levels in the Chorioretina. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 38, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Hancock, S.E.; Phadke, A.; Kansara, V.; Boyer, D.; Rivera, J.; Marlor, C.; Podos, S.; Wiles, J.; McElheny, R.; Ciulla, T.A.; et al. Ocular Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Suprachoroidal A01017, Small Molecule Complement Inhibitor, Injectable Suspension in Rabbits. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 3694. [Google Scholar]Kaiser, P.K.; Ciulla, T.; Kansara, V. Suprachoroidal CLS-AX (Axitinib Injectable Suspension), as a Potential Long-Acting Therapy for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (NAMD). Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 3977. [Google Scholar]Henry, C.R.; Shah, M.; Barakat, M.R.; Dayani, P.; Wang, R.C.; Khurana, R.N.; Rifkin, L.; Yeh, S.; Hall, C.; Ciulla, T. Suprachoroidal CLS-TA for Non-Infectious Uveitis: An Open-Label, Safety Trial (AZALEA). Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Yeh, S.; Khurana, R.N.; Shah, M.; Henry, C.R.; Wang, R.C.; Kissner, J.M.; Ciulla, T.A.; Noronha, G. Efficacy and Safety of Suprachoroidal CLS-TA for Macular Edema Secondary to Noninfectious Uveitis: Phase 3 Randomized Trial. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Henry, C.R.; Kapik, B.; Ciulla, T.A. Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide Injectable Suspension for Macular Edema Associated with Uveitis: Visual and Anatomic Outcomes by Age. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 3206-A0432. [Google Scholar]Merrill, P.T.; Henry, C.R.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Reddy, A.; Kapik, B.; Ciulla, T.A. Suprachoroidal CLS-TA with and without Systemic Corticosteroid and/or Steroid-Sparing Therapy: A Post-Hoc Analysis of the Phase 3 PEACHTREE Clinical Trial. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2021, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Khurana, R.N.; Merrill, P.; Yeh, S.; Suhler, E.; Barakat, M.R.; Uchiyama, E.; Henry, C.R.; Shah, M.; Wang, R.C.; Kapik, B.; et al. Extension Study of the Safety and Efficacy of CLS-TA for Treatment of Macular Oedema Associated with Non-Infectious Uveitis (MAGNOLIA). Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 1139–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Yeh, S.; Kurup, S.K.; Wang, R.C.; Foster, C.S.; Noronha, G.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Do, D.V.; DOGWOOD Study Team. Suprachoroidal injection of triamcinolone acetonide, CLS-TA, for macular edema due to noninfectious uveitis: A Randomized, Phase 2 Study (DOGWOOD). Retina 2019, 39, 1880–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Hanif, J.; Iqbal, K.; Perveen, F.; Arif, A.; Iqbal, R.N.; Jameel, F.; Hanif, K.; Seemab, A.; Khan, A.Y.; Ahmed, M. Safety and Efficacy of Suprachoroidal Injection of Triamcinolone in Treating Macular Edema Secondary to Noninfectious Uveitis. Cureus 2021, 13, e20038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Munir, M.S.; Rehman, R.; Nazir, S.; Sharif, N.; Chaudhari, M.Z.; Saleem, S. Visual Outcome after Suprachoroidal Injection of Triamcinolone Acetate in Cystoid Macular Edema of Different Pathology. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 16, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Qiu, W. Intravitreal Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, Laser Photocoagulation, or Combined Therapy for Diabetic Macular Edema: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1096105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Wykoff, C.C.; Khurana, R.N.; Lampen, S.I.R.; Noronha, G.; Brown, D.M.; Ou, W.C.; Sadda, S.R.; HULK Study Group. Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide for Diabetic Macular Edema: The HULK Trial. Ophthalmol. Retina 2018, 2, 874–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Barakat, M.R.; Wykoff, C.C.; Gonzalez, V.; Hu, A.; Marcus, D.; Zavaleta, E.; Ciulla, T.A. Suprachoroidal CLS-TA plus Intravitreal Aflibercept for Diabetic Macular Edema: A Randomized, Double-Masked, Parallel-Design, Controlled Study. Ophthalmol. Retina 2021, 5, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Fazel, F.; Malekahmadi, M.; Feizi, A.; Oliya, B.; Tavakoli, M.; Fazel, M. Suprachoroidal Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide plus Intravitreal Bevacizumab in Diabetic Macular Edema: A Randomized Pilot Trial. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023, 23, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Shahid, M.H.; Rashid, F.; Tauqeer, S.; Ali, R.; Farooq, M.T.; Aleem, N. Comparison of Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Injection with Intravitreal Bevacizumab Vs Intravitreal Bevacizumab Only in Treatment of Refractory Diabetic Macular Edema. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 16, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Anwar, F.; Khan, A.A.; Majhu, T.M.; Javaid, R.M.M.; Ghaffar, M.T.; Bokhari, M.H. Comparison of Suprachoroidal Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide Versus Intravitreal Bevacizumab in Primary Diabetic Macular Odema. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 16, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Zakaria, Y.G.; Salman, A.G.; Said, A.M.A.; Abdelatif, M.K. Suprachoroidal versus Intravitreal Triamcinolone Acetonide for the Treatment of Diabetic Macular Edema. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 16, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Shaikh, K.; Ahmed, N.; Kazi, U.; Zia, A.; Aziz, M.Z. Comparison between Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone and Intravitreal Triamcinolone Acetonide in Patients of Resistant Diabetic Macular Edema. Pak. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Marashi, A.; Zazo, A. Suprachoroidal Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide Using a Custom-Made Needle to Treat Diabetic Macular Edema Post Pars Plana Vitrectomy: A Case Series. J. Int. Med. Res. 2022, 50, 03000605221089807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Nawar, A.E. Effectiveness of Suprachoroidal Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide in Resistant Diabetic Macular Edema Using a Modified Microneedle. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 16, 3821–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Ateeq, A.; Majid, S.; Memon, N.A.; Hayat, N.; Somroo, A.Q.; Fattah, A. Suprachoroidal Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide for Management of Resistant Diabetic Macular Oedema. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2023, 73, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Chandni, A.; Bhatti, S.R.; Khawer, F.; Ijaz, M.; Rafique, D.; Choudhry, T.A. To Determine the Efficacy of Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Injection for the Treatment of Refractory Diabetic Macular Edema. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 16, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Tayyab, H.; Ahmed, C.N.; Sadiq, M.A.A. Efficacy and Safety of Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide in Cases of Resistant Diabetic Macular Edema. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Ahmad, Y.; Memon, S.U.H.; Bhatti, S.A.; Nawaz, F.; Ahmad, W.; Saleem, M. Efficacy and Safety of Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide in Cases of Resistant Diabetic Macular Edema. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2023, 17, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Butt, S.; Iqbal, R.; Siddiq, S.; Waheed, K.; Javed, T. Efficacy of Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide Injection in the Treatment of Resistant Diabetic Macular Edema. Biol. Clin. Sci. Res. J. 2023, 2023, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Tharwat, E.; Ahmed, R.E.H.; Eltantawy, B.; Ezzeldin, E.R.; Elgazzar, A.F. Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone versus Posterior Subtenon Triamcinolone Either Alone or Formulated in the Management of Diabetic Macular Edema. Int. Ophthalmol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Dhoot, D.S. Suprachoroidal Delivery of RGX-314 for Diabetic Retinopathy: The Phase II ALTITUDE™ Study. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 1152. [Google Scholar]Veiga Reis, F.; Dalgalarrondo, P.; da Silva Tavares Neto, J.E.; Wendeborn Rodrigues, M.; Scott, I.U.; Jorge, R. Combined Intravitreal Dexamethasone and Bevacizumab Injection for the Treatment of Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema (DexaBe Study): A Phase I Clinical Study. Int. J. Retina Vitr. 2023, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Campochiaro, P.A.; Wykoff, C.C.; Brown, D.M.; Boyer, D.S.; Barakat, M.; Taraborelli, D.; Noronha, G.; Tanzanite Study Group. Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide for Retinal Vein Occlusion: Results of the Tanzanite Study. Ophthalmol. Retina 2018, 2, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Clearside Biomedical’s TANZANITE Extension Study in Patients with Macular Edema Associated with Retinal Vein Occlusion Presented at the 40th Annual Macula Society Meeting|Clearside Biomedical, Inc.-IR Site. Available online: https://ir.clearsidebio.com/news-releases/news-release-details/clearside-biomedicals-tanzanite-extension-study-patients-macular (accessed on 15 July 2023).Clearside Biomedical, Inc. SAPPHIRE: A Randomized, Masked, Controlled Trial to Study the Safety and Efficacy of Suprachoroidal CLS-TA in Conjunction with Intravitreal Aflibercept in Subjects with Retinal Vein Occlusion; Clearside Biomedical, Inc.: Alpharetta, GA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]Clearside Biomedical, Inc. A Randomized, Masked, Controlled Trial to Study the Safety and Efficacy of Suprachoroidal CLS-TA in Combination with an Intravitreal Anti-VEGF Agent in Subjects with Retinal Vein Occlusion; Clearside Biomedical, Inc.: Alpharetta, GA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]Nawar, A.E. Modified Microneedle for Suprachoroidal Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide Combined with Intravitreal Injection of Ranibizumab in Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion Patients. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 16, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Ali, B.M.; Azmeh, A.M.; Alhalabi, N.M. Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide for the Treatment of Macular Edema Associated with Retinal Vein Occlusion: A Pilot Study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023, 23, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Muslim, I.; Chaudhry, N.; Javed, R.M.M. Effect of Supra-Choroidal Triamcinolone Injection on Best-Corrected Visual Acuity and Central Retinal Thickness in Patients with Macular Edema Secondary to Retinal Vein Occlusion. Pak. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Rizzo, S.; Ebert, F.G.; Bartolo, E.D.; Barca, F.; Cresti, F.; Augustin, C.; Augustin, A. Suprachoroidal drug Infusion for the Treatment of Severe Subfoveal Hard Exudates. Retina 2012, 32, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Abdelshafy, A. One Year Results for Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide Injection in Various Retinal Diseases; Benha University: Benha, Egypt, 2022. [Google Scholar]Abdelshafy Tabl, A.; Tawfik Soliman, T.; Anany Elsayed, M.; Abdelshafy Tabl, M. A Randomized Trial Comparing Suprachoroidal and Intravitreal Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide in Refractory Diabetic Macular Edema Due to Epiretinal Membrane. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 2022, 7947710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Zhang, D.-D.; Che, D.-Y.; Zhu, D.-Q. A Simple Technique for Suprachoroidal Space Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide in Treatment of Macular Edema. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 15, 2017–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Oli, A.; Waikar, S. Modified Inexpensive Needle for Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide Injections in Pseudophakic Cystoid Macular Edema. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 69, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Marashi, A.; Zazo, A. A Manually Made Needle for Treating Pseudophakic Cystoid Macular Edema by Injecting Triamcinolone Acetonide in the Suprachoroidal Space: A Case Report. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2022, 25, 101254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Abdelshafy, A. Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide Injection in Two Chorioretinal Diseases: One Year Results; Benha University: Benha, Egypt, 2022. [Google Scholar]Martorana, G.; Levine, M.; Peden, M.; Boye, S.; Lukowski, Z.; Min, J.; Meyers, C.; Boye, S.; Sherwood, M. Comparison of Suprachoroidal Delivery via an Ab-Externo Approach with the ITrack Microcatheter versus Vitrectomy and Subretinal Delivery for 3 Different AAV Serotypes for Gene Transfer to the Retina. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 1931. [Google Scholar]Woodard, K.T.; Vance, M.; Gilger, B.; Samulski, R.J.; Hirsch, M. 544. Comparison of AAV Serotype2 Transduction by Various Delivery Routes to the Mouse Eye. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, S217–S218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Ding, K.; Shen, J.; Hafiz, Z.; Hackett, S.F.; Silva, R.L.E.; Khan, M.; Lorenc, V.E.; Chen, D.; Chadha, R.; Zhang, M.; et al. AAV8-Vectored Suprachoroidal Gene Transfer Produces Widespread Ocular Transgene Expression. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 4901–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Ding, K.; Shen, J.; Hackett, S.; Campochiaro, P.A. Transgene Expression in RPE and Retina after Suprachoroidal Delivery of AAV Vectors. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 4490. [Google Scholar]Kansara, V.; Yoo, J.; Cooper, M.J.; Laird, O.S.; Taraborelli, D.; Moen, R.; Noronha, G. Suprachoroidally Delivered Non-Viral DNA Nanoparticles Transfect Chorioretinal Cells in Non-Human Primates and Rabbits. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 2909. [Google Scholar]Chung, S.H.; Mollhoff, I.N.; Mishra, A.; Sin, T.-N.; Ngo, T.; Ciulla, T.; Sieving, P.; Thomasy, S.M.; Yiu, G. Host Immune Responses after Suprachoroidal Delivery of AAV8 in Nonhuman Primate Eyes. Hum. Gene Ther. 2021, 32, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Kansara, V.S.; Cooper, M.; Sesenoglu-Laird, O.; Muya, L.; Moen, R.; Ciulla, T.A. Suprachoroidally Delivered DNA Nanoparticles Transfect Retina and Retinal Pigment Epithelium/Choroid in Rabbits. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Shen, J.; Kim, J.; Tzeng, S.Y.; Ding, K.; Hafiz, Z.; Long, D.; Wang, J.; Green, J.J.; Campochiaro, P.A. Suprachoroidal Gene Transfer with Nonviral Nanoparticles. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Lin, Y.; Ren, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, D. Interaction Between Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Retinal Degenerative Microenvironment. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 617377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Habot-Wilner, Z.; Noronha, G.; Wykoff, C.C. Suprachoroidally Injected Pharmacological Agents for the Treatment of Chorio-Retinal Diseases: A Targeted Approach. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019, 97, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Öner, A.; Kahraman, N.S. Does Stem Cell Implantation Have an Effect on Severity of Retinitis Pigmentosa: Evaluation with a Classification System? Open J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 11, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Oner, A.; Kahraman, N.S. Suprachoroidal Umbilical Cord Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Implantation for the Treatment of Retinitis Pigmentosa in Pediatric Patients. Am. J. Stem Cell Res. 2023, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar]Özkan, B. Suprachoroidal Spheroidal Mesenchymal Stem Cell Implantation in Retinitis Pigmentosa: Clinical Results of 6 Months Follow-Up. 2023. Available online: clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 6 July 2023).Marashi, A.; Baba, M.; Zazo, A. Managing Solar Retinopathy with Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide Injection in a Young Girl: A Case Report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2021, 15, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Gohil, R.; Crosby-Nwaobi, R.; Forbes, A.; Burton, B.; Hykin, P.; Sivaprasad, S. Caregiver Burden in Patients Receiving Ranibizumab Therapy for Neovascular Age Related Macular Degeneration. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Saxena, N.; George, P.P.; Hoon, H.B.; Han, L.T.; Onn, Y.S. Burden of Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Its Economic Implications in Singapore in the Year 2030. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016, 23, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Sampat, K.M.; Garg, S.J. Complications of Intravitreal Injections. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2010, 21, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Fallico, M.; Maugeri, A.; Lotery, A.; Longo, A.; Bonfiglio, V.; Russo, A.; Avitabile, T.; Pulvirenti, A.; Furino, C.; Cennamo, G.; et al. Intravitreal Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors, Panretinal Photocoagulation and Combined Treatment for Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021, 99, e795–e805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Tran, J.; Craven, C.; Wabner, K.; Schmit, J.; Matter, B.; Kompella, U.; Grossniklaus, H.E.; Olsen, T.W. A Pharmacodynamic Analysis of Choroidal Neovascularization in a Porcine Model Using Three Targeted Drugs. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 3732–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Mansoor, S.; Patel, S.R.; Tas, C.; Pacha-Ravi, R.; Kompella, U.B.; Edelhauser, H.F.; Prausnitz, M.R. Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution of Bevacizumab Following Suprachoroidal Injection into the Rabbit Eye Using a Microneedle. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 498. [Google Scholar]Olsen, T.W.; Feng, X.; Wabner, K.; Csaky, K.; Pambuccian, S.; Cameron, J.D. Pharmacokinetics of Pars Plana Intravitreal Injections versus Microcannula Suprachoroidal Injections of Bevacizumab in a Porcine Model. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 4749–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Zeng, M.; Shen, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, L.Y.; Ding, K.; Fortmann, S.D.; Khan, M.; Wang, J.; Hackett, S.F.; Semenza, G.L.; et al. The HIF-1 Antagonist Acriflavine: Visualization in Retina and Suppression of Ocular Neovascularization. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 95, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Olsen, T.W.; Sanderson, S.; Feng, X.; Hubbard, W.C. Porcine Sclera: Thickness and Surface Area. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 2529–2532. [Google Scholar]AbbVie. A Phase 2, Randomized, Dose-Escalation, Ranibizumab-Controlled Study to Evaluate the Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of RGX-314 Gene Therapy Delivered Via One or Two Suprachoroidal Space (SCS) Injections in Participants with Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (NAMD) (AAVIATE); AbbVie: Wellington, New Zealand, 2023. [Google Scholar]Khanani, A.M. Suprachoroidal Delivery of RGX-314 Gene Therapy for Neovascular AMD: The Phase II AAVIATE™ Study. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 1497. [Google Scholar]Tetz, M.; Rizzo, S.; Augustin, A.J. Safety of Submacular Suprachoroidal Drug Administration via a Microcatheter: Retrospective Analysis of European Treatment Results. Ophthalmologica 2012, 227, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Morales-Canton, V.; Fromow-Guerra, J.; Salinas Longoria, S.; Romero Vera, R.; Widmann, M.; Patel, S.; Yerxa, B. Suprachoroidal Microinjection of Bevacizumab Is Well Tolerated in Human Patients. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 3299. [Google Scholar]Patel, S.R.; Kissner, J.; Farjo, R.; Zarnitsyn, V.; Noronha, G. Efficacy of Suprachoroidal Aflibercept in a Laser Induced Choroidal Neovascularization Model. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 286. [Google Scholar]Kissner, J.; Patel, S.R.; Prusakiewicz, J.J.; Alton, D.; Bikzhanova, G.; Geisler, L.; Burke, B.; Noronha, G. Pharmacokinetics including Ocular Distribution Characteristics of Suprachoroidally Administered CLS011A in Rabbits Could Be Beneficial for a Wet AMD Therapeutic Candidate; ASSOC Research Vision Ophthalmology Inc.: Seattle, WA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]Clearside Biomedical, Inc. OASIS: Open-Label, Dose-Escalation, Phase 1/2a Study of the Safety and Tolerability of Suprachoroidally Administered CLS-AX Following Intravitreal Anti-VEGF Therapy in Subjects with Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration; Clearside Biomedical, Inc.: Alpharetta, GA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]Clearside Biomedical, Inc. Extension Study to Evaluate the Long-Term Outcomes of Subjects Following CLS-AX Administration for Age-Related Macular Degeneration in the CLS-AX CLS1002-101 Study; Clearside Biomedical, Inc.: Alpharetta, GA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]Shanghai BDgene Co., Ltd. A Safety and Efficacy Study of VEGFA-Targeting Gene Therapy to Treat Refractory Retinal and Choroidal Neovascularization Diseases; Shanghai BDgene Co., Ltd.: Shanghai, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]Datta, D.; Khan, P.; Khan, L.; Singh, A. Role of Suprachoroidal Anti-VEGF Injections in Recalcitrant Serous Pigment Epithelium Detachment. Ophthalmol. Res. Int. J. 2023, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Kohli, G.M.; Shenoy, P.; Halim, D.; Nigam, S.; Shetty, S.; Talwar, D.; Sen, A. Safety and Efficacy of Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide for the Management of Serous Choroidal Detachment Prior to Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment Surgery: A Pilot Study. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 70, 1302–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Tabl, A.A.; Elsayed, M.A.; Tabl, M.A. Suprachoroidal Triamcinolone Acetonide Injection: A Novel Therapy for Serous Retinal Detachment Due to Vogt-Koyanagi Harada Disease. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 32, 3482–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Gao, Y.; An, J.; Zeng, Z.; Lou, H.; Wu, G.; Lu, F. Suprachoroidal injection of sodium hyaluronate in the treatment of 12 patients with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Chin. J. Ocul. Fundus Dis. 2019, 6, 274–278. [Google Scholar]Mittl, R.N.; Tiwari, R. Suprachoroidal Injection of Sodium Hyaluronate as an “internal” Buckling Procedure. Ophthalmic Res. 1987, 19, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Smith, R. Suprachoroidal Air Injection for Detached Retina. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1952, 36, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Goldstein, D.A.; Do, D.; Noronha, G.; Kissner, J.M.; Srivastava, S.K.; Nguyen, Q.D. Suprachoroidal Corticosteroid Administration: A Novel Route for Local Treatment of Noninfectious Uveitis. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2016, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Noronha, G.; Blackwell, K.; Gilger, B.C.; Kissner, J.; Patel, S.R.; Walsh, K.T. Evaluation of Suprachoroidal CLS-TA and Oral Prednisone in a Porcine Model of Uveitis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 3110. [Google Scholar]Gilger, B.C.; Abarca, E.M.; Salmon, J.H.; Patel, S. Treatment of Acute Posterior Uveitis in a Porcine Model by Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide into the Suprachoroidal Space Using Microneedles. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 2483–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Patel, S.; Carvalho, R.; Mundwiler, K.; Meschter, C.; Verhoeven, R. Evaluation of Suprachoroidal Microinjection of Triamcinolone Acetonide in a Model of Panuveitis in Albino Rabbits. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 2927. [Google Scholar]Ghate, D.; Edelhauser, H.F. Barriers to Glaucoma Drug Delivery. J. Glaucoma 2008, 17, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Konstas, A.G.; Stewart, W.C.; Topouzis, F.; Tersis, I.; Holmes, K.T.; Stangos, N.T. Brimonidine 0.2% given Two or Three Times Daily versus Timolol Maleate 0.5% in Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2001, 131, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Robin, A.L.; Novack, G.D.; Covert, D.W.; Crockett, R.S.; Marcic, T.S. Adherence in Glaucoma: Objective Measurements of Once-Daily and Adjunctive Medication Use. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 144, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Gurwitz, J.H.; Glynn, R.J.; Monane, M.; Everitt, D.E.; Gilden, D.; Smith, N.; Avorn, J. Treatment for Glaucoma: Adherence by the Elderly. Am. J. Public Health 1993, 83, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Kim, Y.C.; Edelhauser, H.F.; Prausnitz, M.R. Targeted Delivery of Antiglaucoma Drugs to the Supraciliary Space Using Microneedles. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 7387–7397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Chiang, B.; Kim, Y.C.; Doty, A.C.; Grossniklaus, H.E.; Schwendeman, S.P.; Prausnitz, M.R. Sustained Reduction of Intraocular Pressure by Supraciliary Delivery of Brimonidine-Loaded Poly(Lactic Acid) Microspheres for the Treatment of Glaucoma. J. Control. Release 2016, 228, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Einmahl, S.; Savoldelli, M.; D’Hermies, F.; Tabatabay, C.; Gurny, R.; Behar-Cohen, F. Evaluation of a Novel Biomaterial in the Suprachoroidal Space of the Rabbit Eye. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 1533–1539. [Google Scholar]Chae, J.J.; Jung, J.H.; Zhu, W.; Gerberich, B.G.; Bahrani Fard, M.R.; Grossniklaus, H.E.; Ethier, C.R.; Prausnitz, M.R. Drug-Free, Nonsurgical Reduction of Intraocular Pressure for Four Months after Suprachoroidal Injection of Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2001908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Hao, H.; He, B.; Yu, B.; Yang, J.; Xing, X.; Liu, W. Suprachoroidal Injection of Polyzwitterion Hydrogel for Treating Glaucoma. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 142, 213162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Savinainen, A.; Grossniklaus, H.E.; King, S.; Wicks, J.; Rich, C.C. Ocular Distribution and Exposure of AU-011 after Suprachoroidal or Intravitreal Administration in an Orthotopic Rabbit Model of Human Uveal Melanoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 2861. [Google Scholar]Kang, S.J.; Patel, S.R.; Berezovsky, D.E.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.; Grossniklaus, H.E. Suprachoroidal Injection of Microspheres with Microcatheter in a Rabbit Model of Uveal Melanoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 1459. [Google Scholar]Mruthyunjaya, P.; Schefler, A.C.; Kim, I.K.; Bergstrom, C.; Demirci, H.; Tsai, T.; Bhavsar, A.R.; Capone, A.; Marr, B.; McCannel, T.A.; et al. A Phase 1b/2 Open-Label Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of AU-011 for the Treatment of Choroidal Melanoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 4025. [Google Scholar]Demirci, H.; Narvekar, A.; Murray, C.; Rich, C. 842P A Phase II Trial of AU-011, an Investigational, Virus-like Drug Conjugate (VDC) for the Treatment of Primary Indeterminate Lesions and Small Choroidal Melanoma (IL/CM) Using Suprachoroidal Administration. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, S934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Peddada, K.V.; Sangani, R.; Menon, H.; Verma, V. Complications and Adverse Events of Plaque Brachytherapy for Ocular Melanoma. J. Contemp. Brachyther. 2019, 11, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Aura Biosciences. A Phase 2 Open-Label, Ascending Single and Repeat Dose Escalation Trial of Belzupacap Sarotalocan (AU-011) via Suprachoroidal Administration in Subjects with Primary Indeterminate Lesions and Small Choroidal Melanoma; Aura Biosciences: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]Venkatesh, P.; Takkar, B. Suprachoroidal Injection of Biological Agents May Have a Potential Role in the Prevention of Progression and Complications in High Myopia. Med. Hypotheses 2017, 107, 90–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Morgan, I.G.; Ohno-Matsui, K.; Saw, S.-M. Myopia. Lancet 2012, 379, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Gaynes, B.I.; Fiscella, R. Topical Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs for Ophthalmic Use: A Safety Review. Drug Saf. 2002, 25, 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Kompella, U.B.; Kadam, R.S.; Lee, V.H.L. Recent Advances in Ophthalmic Drug Delivery. Ther. Deliv. 2010, 1, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Wang, M.; Liu, W.; Lu, Q.; Zeng, H.; Liu, S.; Yue, Y.; Cheng, H.; Liu, Y.; Xue, M. Pharmacokinetic Comparison of Ketorolac after Intracameral, Intravitreal, and Suprachoroidal Administration in Rabbits. Retina 2012, 32, 2158–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Liu, S.; Liu, W.; Ma, Y.; Liu, K.; Wang, M. Suprachoroidal Injection of Ketorolac Tromethamine Does Not Cause Retinal Damage. Neural Regen. Res. 2012, 7, 2770–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Maldonado, R.M.; Vianna, R.N.G.; Cardoso, G.P.; de Magalhães, A.V.; Burnier, M.N. Intravitreal Injection of Commercially Available Ketorolac Tromethamine in Eyes with Diabetic Macular Edema Refractory to Laser Photocoagulation. Curr. Eye Res. 2011, 36, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Giannantonio, C.; Papacci, P.; Purcaro, V.; Cota, F.; Tesfagabir, M.G.; Molle, F.; Lepore, D.; Baldascino, A.; Romagnoli, C. Effectiveness of Ketorolac Tromethamine in Prevention of Severe Retinopathy of Prematurity. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 2011, 48, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Margalit, E.; Boysen, J.L.; Zastrocky, J.P.; Katz, A. Use of Intraocular Ketorolac Tromethamine for the Treatment of Chronic Cystoid Macular Edema. Can. J. Ophthalmol. J. Can. Ophtalmol. 2010, 45, 409–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Kim, S.J.; Toma, H.S. Inhibition of Choroidal Neovascularization by Intravitreal Ketorolac. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2010, 128, 596–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Willoughby, A.S.; Vuong, V.S.; Cunefare, D.; Farsiu, S.; Noronha, G.; Danis, R.P.; Yiu, G. Choroidal Changes after Suprachoroidal Injection of Triamcinolone in Eyes with Macular Edema Secondary to Retinal Vein Occlusion. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 186, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]Tian, B.; Xie, J.; Su, W.; Sun, S.; Su, Q.; Gao, G.; Lin, H. Suprachoroidal Injections of AAV for Retinal Gene Delivery in Mouse. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 1177. [Google Scholar]Wiley, L.A.; Boyce, T.M.; Meyering, E.E.; Ochoa, D.; Sheehan, K.M.; Stone, E.M.; Mullins, R.F.; Tucker, B.A.; Han, I.C. The Degree of Adeno-Associated Virus-Induced Retinal Inflammation Varies Based on Serotype and Route of Delivery: Intravitreal, Subretinal, or Suprachoroidal. Hum. Gene Ther. 2023, 34, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Han, I.C.; Cheng, J.L.; Burnight, E.R.; Ralston, C.L.; Fick, J.L.; Thomsen, G.J.; Tovar, E.F.; Russell, S.R.; Sohn, E.H.; Mullins, R.F.; et al. Retinal Tropism and Transduction of Adeno-Associated Virus Varies by Serotype and Route of Delivery (Intravitreal, Subretinal, or Suprachoroidal) in Rats. Hum. Gene Ther. 2020, 31, 1288–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Kahraman, N.S.; Gonen, Z.B.; Sevim, D.G.; Oner, A. First Year Results of Suprachoroidal Adipose Tissue Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Implantation in Degenerative Macular Diseases. Int. J. Stem Cells 2021, 14, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]Muya, L.; Kansara, V.; Ciulla, T. Pharmacokinetics and Ocular Tolerability of Suprachoroidal CLS-AX (Axitinib Injectable Suspension) in Rabbits. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 4925. [Google Scholar]Ghate, D.; Edelhauser, H.F. Ocular Drug Delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2006, 3, 275–287.

- Wu, K.Y.; Ashkar, S.; Jain, S.; Marchand, M.; Tran, S.D. Breaking Barriers in Eye Treatment: Polymeric Nano-Based Drug-Delivery System for Anterior Segment Diseases and Glaucoma. Polymers 2023, 15, 1373.

- Carnahan, M.C.; Goldstein, D.A. Ocular Complications of Topical, Peri-Ocular, and Systemic Corticosteroids. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2000, 11, 478–483.

- Tyagi, P.; Kadam, R.S.; Kompella, U.B. Comparison of Suprachoroidal Drug Delivery with Subconjunctival and Intravitreal Routes Using Noninvasive Fluorophotometry. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48188.

- Yiu, G.; Chung, S.H.; Mollhoff, I.N.; Nguyen, U.T.; Thomasy, S.M.; Yoo, J.; Taraborelli, D.; Noronha, G. Suprachoroidal and Subretinal Injections of AAV Using Transscleral Microneedles for Retinal Gene Delivery in Nonhuman Primates. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 16, 179–191.

- Agrahari, V.; Mandal, A.; Agrahari, V.; Trinh, H.M.; Joseph, M.; Ray, A.; Hadji, H.; Mitra, R.; Pal, D.; Mitra, A.K. A Comprehensive insight on ocular pharmacokinetics. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2016, 6, 735–754.

- Loftsson, T.; Stefánsson, E. Aqueous Eye Drops Containing Drug/Cyclodextrin Nanoparticles Deliver Therapeutic Drug Concentrations to Both Anterior and Posterior Segment. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022, 100, 7–25.

- Uchino, M.; Yokoi, N.; Shimazaki, J.; Hori, Y.; Tsubota, K.; on behalf of the Japan Dry Eye Society. Adherence to Eye Drops Usage in Dry Eye Patients and Reasons for Non-Compliance: A Web-Based Survey. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 367.

- Foley, L.; Larkin, J.; Lombard-Vance, R.; Murphy, A.W.; Hynes, L.; Galvin, E.; Molloy, G.J. Prevalence and Predictors of Medication Non-Adherence among People Living with Multimorbidity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044987.

- Holló, G. The Side Effects of the Prostaglandin Analogues. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2007, 6, 45–52.

- Santulli, R.J.; Kinney, W.A.; Ghosh, S.; Decorte, B.L.; Liu, L.; Tuman, R.W.A.; Zhou, Z.; Huebert, N.; Bursell, S.E.; Clermont, A.C.; et al. Studies with an Orally Bioavailable Alpha V Integrin Antagonist in Animal Models of Ocular Vasculopathy: Retinal Neovascularization in Mice and Retinal Vascular Permeability in Diabetic Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 324, 894–901.

- Shirasaki, Y.; Miyashita, H.; Yamaguchi, M. Exploration of Orally Available Calpain Inhibitors. Part 3: Dipeptidyl Alpha-Ketoamide Derivatives Containing Pyridine Moiety. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 5691–5698.

- Kampougeris, G.; Antoniadou, A.; Kavouklis, E.; Chryssouli, Z.; Giamarellou, H. Penetration of Moxifloxacin into the Human Aqueous Humour after Oral Administration. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 89, 628–631.

- Sakamoto, H.; Sakamoto, M.; Hata, Y.; Kubota, T.; Ishibashi, T. Aqueous and Vitreous Penetration of Levofloxacin after Topical and/or Oral Administration. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 17, 372–376.

- hirasaki, Y. Molecular Design for Enhancement of Ocular Penetration. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 2462–2496.

- Kaur, I.P.; Smitha, R.; Aggarwal, D.; Kapil, M. Acetazolamide: Future Perspective in Topical Glaucoma Therapeutics. Int. J. Pharm. 2002, 248, 1–14.

- Gipson, I.K.; Argüeso, P. Role of Mucins in the Function of the Corneal and Conjunctival Epithelia. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2003, 231, 1–49.

- Geroski, D.H.; Edelhauser, H.F. Transscleral Drug Delivery for Posterior Segment Disease. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 52, 37–48.

- Hosseini, K.; Matsushima, D.; Johnson, J.; Widera, G.; Nyam, K.; Kim, L.; Xu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Cormier, M. Pharmacokinetic Study of Dexamethasone Disodium Phosphate Using Intravitreal, Subconjunctival, and Intravenous Delivery Routes in Rabbits. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 24, 301–308.

- Weijtens, O.; Feron, E.J.; Schoemaker, R.C.; Cohen, A.F.; Lentjes, E.G.; Romijn, F.P.; van Meurs, J.C. High Concentration of Dexamethasone in Aqueous and Vitreous after Subconjunctival Injection. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1999, 128, 192–197.

- Kim, S.H.; Csaky, K.G.; Wang, N.S.; Lutz, R.J. Drug Elimination Kinetics Following Subconjunctival Injection Using Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 512–520.

- Prausnitz, M.R.; Noonan, J.S. Permeability of Cornea, Sclera, and Conjunctiva: A Literature Analysis for Drug Delivery to the Eye. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998, 87, 1479–1488.

- Modi, Y.S.; Tanchon, C.; Ehlers, J.P. Comparative Safety and Tolerability of Anti-VEGF Therapy in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Drug Saf. 2015, 38, 279–293.

- Massa, H.; Nagar, A.M.; Vergados, A.; Dadoukis, P.; Patra, S.; Panos, G.D. Intravitreal Fluocinolone Acetonide Implant (ILUVIEN®) for Diabetic Macular Oedema: A Literature Review. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 31–43.

- Adelman, R.A.; Parnes, A.J.; Bopp, S.; Saad Othman, I.; Ducournau, D. Strategy for the Management of Macular Edema in Retinal Vein Occlusion: The European VitreoRetinal Society Macular Edema Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 870987.

- Gao, L.; Zhao, X.; Jiao, L.; Tang, L. Intravitreal Corticosteroids for Diabetic Macular Edema: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eye Vis. 2021, 8, 35.

- Hussain, R.M.; Hariprasad, S.M.; Ciulla, T.A. Treatment Burden in Neovascular AMD:Visual Acuity Outcomes Are Associated with Anti-VEGF Injection Frequency. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retina 2017, 48, 780–784.

- Ciulla, T.A.; Bracha, P.; Pollack, J.; Williams, D.F. Real-World Outcomes of Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapy in Diabetic Macular Edema in the United States. Ophthalmol. Retina 2018, 2, 1179–1187.

- Ciulla, T.; Pollack, J.S.; Williams, D.F. Visual Acuity Outcomes and Anti-VEGF Therapy Intensity in Macular Oedema Due to Retinal Vein Occlusion: A Real-World Analysis of 15 613 Patient Eyes. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 105, 1696–1704.

- Chin, H.-S.; Park, T.-S.; Moon, Y.-S.; Oh, J.-H. Difference in clearance of intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide between vitrectomized and nonvitrectomized eyes. Retina 2005, 25, 556–560.

- Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment Trial Research Group. The Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment (MUST) Trial: Rationale, Design and Baseline Characteristics. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 149, 550–561.e10.

- Writing Committee for the Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment (MUST) Trial and Follow-up Study Research Group. Association between Long-Lasting Intravitreous Fluocinolone Acetonide Implant vs. Systemic Anti-Inflammatory Therapy and Visual Acuity at 7 Years Among Patients with Intermediate, Posterior, or Panuveitis. JAMA 2017, 317, 1993–2005.

- Holekamp, N.M.; Campochiaro, P.A.; Chang, M.A.; Miller, D.; Pieramici, D.; Adamis, A.P.; Brittain, C.; Evans, E.; Kaufman, D.; Maass, K.F.; et al. Archway Randomized Phase 3 Trial of the Port Delivery System with Ranibizumab for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, 295–307.

- Heier, J.S.; Khanani, A.M.; Quezada Ruiz, C.; Basu, K.; Ferrone, P.J.; Brittain, C.; Figueroa, M.S.; Lin, H.; Holz, F.G.; Patel, V.; et al. Efficacy, Durability, and Safety of Intravitreal Faricimab up to Every 16 Weeks for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (TENAYA and LUCERNE): Two Randomised, Double-Masked, Phase 3, Non-Inferiority Trials. Lancet 2022, 399, 729–740.

- Genentech: Press Releases|Friday, 28 January 2022. Available online: https://www.gene.com/media/press-releases/14943/2022-01-28/fda-approves-genentechs-vabysmo-the-firs (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Genentech: Press Releases|Friday, 22 October 2021. Available online: https://www.gene.com/media/press-releases/14935/2021-10-22/fda-approves-genentechs-susvimo-a-first- (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Pitkänen, L.; Ruponen, M.; Nieminen, J.; Urtti, A. Vitreous Is a Barrier in Nonviral Gene Transfer by Cationic Lipids and Polymers. Pharm. Res. 2003, 20, 576–583.

- Peeters, L.; Sanders, N.N.; Braeckmans, K.; Boussery, K.; Van de Voorde, J.; De Smedt, S.C.; Demeester, J. Vitreous: A Barrier to Nonviral Ocular Gene Therapy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005, 46, 3553–3561.

- Dalkara, D.; Kolstad, K.D.; Caporale, N.; Visel, M.; Klimczak, R.R.; Schaffer, D.V.; Flannery, J.G. Inner Limiting Membrane Barriers to AAV-Mediated Retinal Transduction from the Vitreous. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2009, 17, 2096–2102.

- Kansara, V.; Muya, L.; Wan, C.-R.; Ciulla, T.A. Suprachoroidal Delivery of Viral and Nonviral Gene Therapy for Retinal Diseases. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 36, 384–392.

- Mahabadi, N.; Al Khalili, Y. Neuroanatomy, Retina. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023.

- Russell, S.; Bennett, J.; Wellman, J.A.; Chung, D.C.; Yu, Z.-F.; Tillman, A.; Wittes, J.; Pappas, J.; Elci, O.; McCague, S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Voretigene Neparvovec (AAV2-HRPE65v2) in Patients with RPE65-Mediated Inherited Retinal Dystrophy: A Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 849–860.

- Maguire, A.M.; Russell, S.; Chung, D.C.; Yu, Z.-F.; Tillman, A.; Drack, A.V.; Simonelli, F.; Leroy, B.P.; Reape, K.Z.; High, K.A.; et al. Durability of Voretigene Neparvovec for Biallelic RPE65-Mediated Inherited Retinal Disease: Phase 3 Results at 3 and 4 Years. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 1460–1468.

- REGENXBIO Announces Additional Positive Interim Phase I/IIa and Long-Term Follow-Up Data of RGX-314 for the Treatment of Wet AMD|Regenxbio Inc. Available online: https://ir.regenxbio.com/news-releases/news-release-details/regenxbio-announces-additional-positive-interim-phase-iiia-and/ (accessed on 6 July 2023).