Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Peter Tang and Version 1 by Yensen Ni.

Customer mistreatment is a reflection of poor customer behaviors, which include speaking loudly, verbal abuse, making unfair demands, skipping a queue, and other disrespectful behaviors. Customer mistreatment may be an unavoidable issue for the hospitality industry.

- customer mistreatment

- emotional exhaustion

- turnover intention

- mindfulness

- hospitality employees

1. Introduction

Customer mistreatment is a reflection of poor customer behaviors [1], which include speaking loudly, verbal abuse, making unfair demands, skipping a queue, and other disrespectful behaviors [2]. Employees who experience customer mistreatment may experience emotional distress [3], emotional exhaustion [4], poor physical health [5], poor job performance [6], and absenteeism [7]. Since employee turnover has received increased attention in the hotel industry [8], wthe researchers propose that if employees are frequently mistreated by customers, turnover intention and work withdrawal may eventually increase [9]. For example, a customer at a busy hotel restaurant becomes irate due to a delayed order. They raise their voice and make unreasonable demands, causing distress to the server (hospitality employee). This public conflict not only disrupts the dining experience but also affects the server’s emotional well-being and overall job performance, potentially contributing to high turnover rates in the hospitality industry. As a result, the study of negative customer–employee interactions is crucial for the hospitality industry due to their increasing prevalence and negative impacts on employees, as described above, highlighting the need to investigate this issue and even provide solutions for hospitality businesses.

Previous research has found that several internal factors, including organizational factors [8[8][10],10], managerial factors [11], and individual personal factors [12], influence employee turnover intention. WThe researchers argue that external factors play an important role in influencing employee turnover [9]. However, the effects of external factors (e.g., customer mistreatment) on employee turnover intention appear to be understudied.

Customer mistreatment, a type of poor treatment from customers, is regarded as an external source that influences employee emotion, potentially leading to work withdrawal behavior and a greater turnover of employees [9]. Thus, wthe researchers argue that looking for ways to mitigate the adverse effects of customer mistreatment is worthwhile because customer mistreatment interfering with employee performance is a critical issue for the hotel industry. Mindfulness meditation practices are deliberate acts of attention regulation through the observation of thoughts, emotions, and body states that can be used as adjunctive treatments for anxiety disorders [13]. Previous research has shown that mindfulness can help individuals reduce emotional exhaustion [14[14][15],15], improve their quality of life [16], and maintain good habits [17]. Furthermore, mindfulness is gaining traction in the hospitality industry; for example, some hotels provide mindfulness training/advice to both employees and customers [18,19][18][19].

2. Customer Mistreatment

Customers and employees frequently interact with one another. However, in the service industry, the frequent occurrence of customer maltreatment towards employees (e.g., speaking loudly, verbal abuse, unfair demands, jumping a queue, and ill-mannered behaviors) remains a source of concern. Furthermore, as one of the key factors influencing employee emotions, customer mistreatment has numerous side effects on employees [4], frequently resulting in strong emotional reactions among employees [25][20]. Moreover, previous research has shown that customer mistreatment hurts employees’ health [26][21] and increases their emotional exhaustion [1]. Previous studies have aimed to address the behavioral impact of employees’ unpleasant feelings produced by customer mistreatment. According to Huang et al. (2019) [27][22], employee sabotage may be a response to customer maltreatment, although Baranik et al. (2017) [1] argue that cognitive rumination may attenuate customer mistreatment and reduce employee sabotage. Social sharing, such as talking to coworkers, is also a popular response to customer mistreatment [4]. Customer mistreatment’s consequences on employees’ jobs and careers have also been studied since customer mistreatment can change employees’ feelings and behavior. For example, relevant research has shown that when customers mistreat hospitality employees, their service performance suffers [28][23]; prior research has also shown that customer mistreatment negatively impacts restaurant personnel’s service performance [22][24], lowers service performance among hospitality employees such as tour guides and frontline staff [29][25], and, even worse, increases employee absenteeism [30][26]. Employees are not only harmed when customers are mistreating them, but the consequences are likely to last a long time. According to Shi and Wang (2022) [4], negative emotions caused by customer mistreatment may linger even longer the next day. Many moderating and intervention factors have been proposed gradually because employees’ persistent negative emotions are likely to be detrimental to business. Relevant research suggests that both self-esteem and age [6] alleviate the influence of customer mistreatment on self-confidence threat. Overall, wthe researchers believe that more research into how to effectively lessen the negative influence of consumer mistreatment is required. Frequent interactions between customers and service employees in the service industry have given rise to an ongoing issue of unfavorable interactions, including behaviors such as speaking loudly, verbal abuse, making unreasonable demands, queue jumping, and ill-mannered conduct. This persistent problem of customer mistreatment has raised significant concerns within the field [4]. It is worth noting that customer mistreatment not only impacts employees’ emotions but also leads to a multitude of adverse consequences for them [4]. As a critical factor influencing employee emotions, it frequently triggers intense emotional responses among them [25][20]. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that customer mistreatment can have detrimental effects on employees’ health [26][21] and contribute to heightened emotional exhaustion [1]. Previous research has predominantly concentrated on the behavioral repercussions stemming from employees’ unpleasant emotions derived from customer mistreatment [31,32][27][28]. While Huang et al. (2019) [27][22] argue that employee sabotage can be a response to customer maltreatment, Baranik et al. (2017) [1] suggest that cognitive rumination might mitigate the effects of customer mistreatment and reduce employee sabotage. Social sharing, such as discussing their experiences with coworkers, is another common response to customer mistreatment [4]. Moreover, the consequences of customer mistreatment on employees’ job performance and career prospects have garnered significant research attention, as it fundamentally alters employees’ emotions and behaviors. For instance, pertinent research has demonstrated that when customers mistreat hospitality employees, it negatively affects their service performance [28][23]. Similarly, customer mistreatment diminishes the service performance of restaurant staff [22][24] and leads to decreased service quality in hospitality employees such as tour guides and frontline staff [29][25]. In more severe cases, consumer incivility has been linked to increased employee absenteeism [30][26]. Importantly, the repercussions of customer mistreatment on employees are not short-lived; they can persist over an extended period. According to Shi and Wang (2022) [4], negative emotions triggered by customer mistreatment may carry over to the following day [33][29]. Given the potential harm to businesses, numerous moderating and intervention factors have been proposed. Relevant research suggests that both self-esteem and age may alleviate the effect of customer mistreatment on self-confidence threats [6]. As such, it is essential to conduct additional research to mitigate the negative impact of consumer mistreatment on either employees or businesses.3. Pressure–State–Response (PSR) Framework

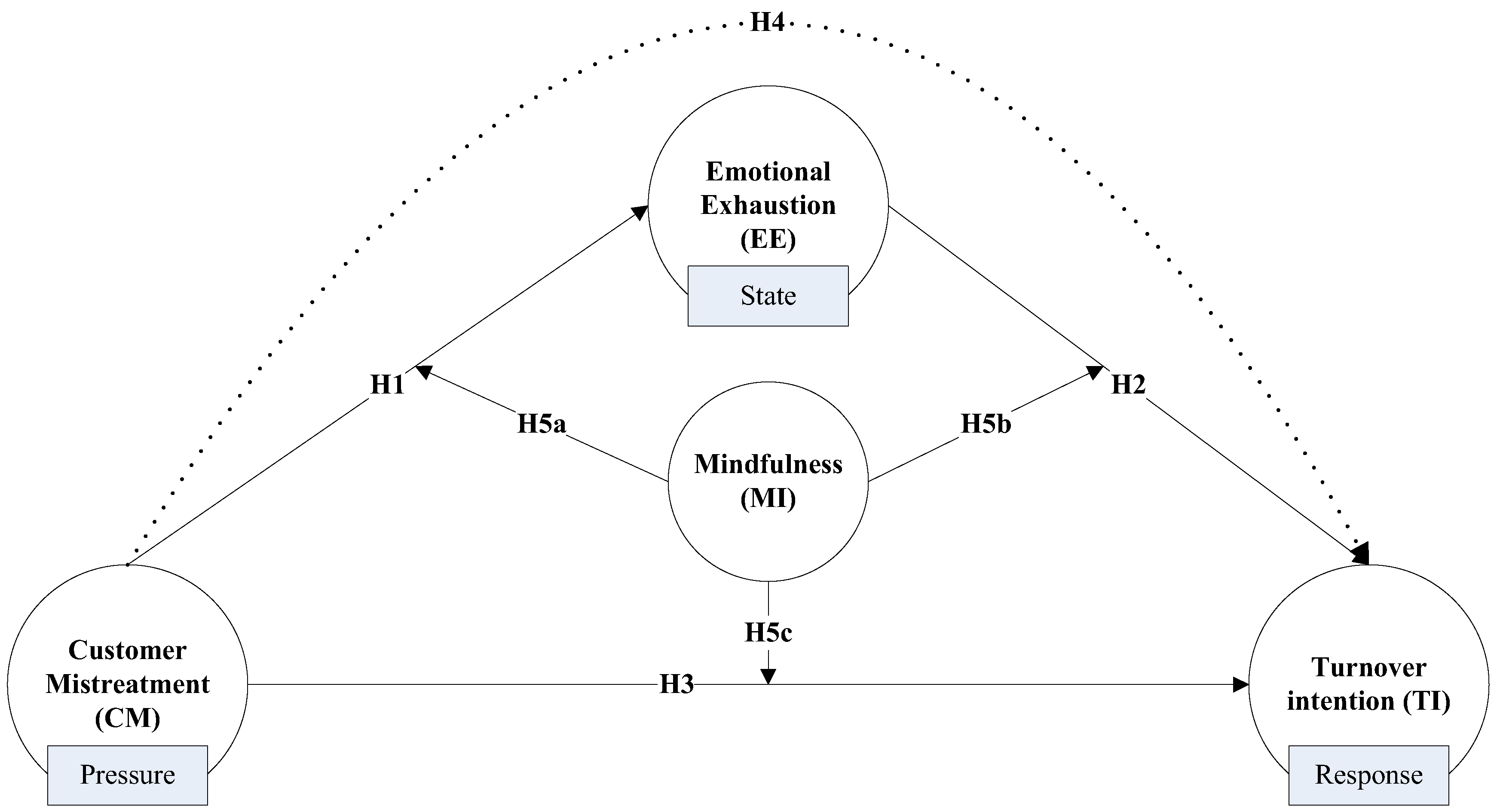

The Pressure–State–Response (PSR) framework is widely employed in the field of ecology [34][30]. This framework includes three main components: pressure, state, and response [35][31]. The PSR framework is also a useful tool for explaining a system’s interaction with external influencing factors by way of capturing the dynamic changes and primary reasoning of events. For example, when people feel pressure from outside factors (P), it may lead to changes in their state (S) that, in turn, lead to a reaction (R) that attempts to relieve the pressure. Customer mistreatment, as elucidated by Shin et al. (2021) [36][32], places considerable stress on employees and depletes their resources, thereby subjecting service workers to significant strain [7]. According to the PSR framework, customer mistreatment can be regarded as an external force exerting pressure on employees. Emotional exhaustion, which is characterized as stress-induced depletion [37][33], represents a state of both physical and mental fatigue resulting from a deficiency in energy and resources. Within the PSR framework, emotional exhaustion is treated as a state component for employees subjected to the pressure of customer mistreatment. Previous research has explored various response factors, including behavioral and revisit intentions [38,39][34][35]. In outhe r study, weesearch, researchers have chosen employee turnover intention as the response factor. In Figure 1, wthe researchers present the conceptual framework that weas used to elucidate the connections among these factors. In the framework, customer mistreatment is the pressure factor, emotional exhaustion is the state factor, turnover intention is the response factor, and mindfulness is the moderating factor. After deciding to use this framework for the present study, weresearch, researchers proposed several pivotal hypotheses for further investigation.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework.

4. The Mediation of Emotional Exhaustion

According to the PSR framework, the state factor (emotional exhaustion) can serve as a link between the pressure factor (customer mistreatment) and the response factor (turnover intention). In addition, emotional exhaustion may mediate the links between customer mistreatment and job satisfaction [48][46], job demands and instigated workplace incivility [51][49], and workplace ostracism and interpersonal deviance [52][50]. Furthermore, employees’ emotional exhaustion may serve as a crucial mediator in the relationship between customer mistreatment and turnover intention. When mistreated by customers, employees often experience heightened emotional exhaustion [53][51], prompting them to consider leaving their jobs in search of relief from these emotionally draining interactions [54][52].5. The Moderation of Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a deliberate and nonjudgmental focus on the present moment [55][53]. To regulate attention, mindfulness meditation involves observing thoughts, emotions, and body states [56][54]. Mindfulness may provide people with a sense of control and a pleasant affective consequence because it involves conscious awareness, non-subjective judgment, and present moment focus [56][54]. Individuals with high-level mindfulness might recover from negative emotions more quickly due to their ability to recognize reality without becoming confused [57][55]. Furthermore, relevant research has shown that mindfulness positively affects psychological distress [58][56], experience [59][57], and long-term sustainable behavior [57][55]. Previous research has shown that employee emotional exhaustion may be mitigated by mindfulness [14,42][14][38]. People who practice mindfulness may analyze the current situation before making decisions rather than relying on experience [17], and mindfulness may help to moderate the link between environmental influences and one’s emotional state [60][58]. Additionally, by utilizing mindfulness, employees may develop better emotional regulation skills [17], helping them cope with mistreatment more effectively and reducing the impact of such experiences on their emotional exhaustion [61][59]. According to previous studies, tourists who practice mindfulness are more likely to modify their behavior because they may be aware of how their actions affect others [17]; mindfulness can stimulate an individual’s self-regulating activities by reducing stress, likely resulting in fewer defensive responses [62][60], and mindfulness has been shown to be associated with self-control but not impulsive actions such as physical and verbal aggression [63][61]. Additionally, practicing mindfulness can enhance employees’ resilience and coping mechanisms, making them less likely to consider leaving their jobs when experiencing emotional exhaustion [64][62]. Additionally, employees who practice mindfulness can better handle the emotional impact of mistreatment, lowering their intention to leave as they become more resilient and adaptable in facing customer mistreatment [65][63].References

- Baranik, L.E.; Wang, M.; Gong, Y.; Shi, J. Customer Mistreatment, Employee Health, and Job Performance: Cognitive Rumination and Social Sharing as Mediating Mechanisms. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1261–1282.

- Shaheer, I.; Carr, N. Social representations of tourists’ deviant behaviours: An analysis of Reddit comments. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 24, 689–700.

- Hwang, K.; Lee, B. Pride, mindfulness, public self-awareness, affective satisfaction, and customer citizenship behaviour among green restaurant customers. Int. J. Hosp. Mgmt. 2019, 83, 169–179.

- Shi, X.; Wang, X. Daily spillover from home to work: The role of workplace mindfulness and daily customer mistreatment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Mgmt. 2022, 34, 3008–3028.

- Lu, W.; Liu, S.; Wu, H.; Wu, K.; Pei, J. To avoidance or approach: Unraveling hospitality employees’ job crafting behavior response to daily customer mistreatment. J. Hosp. Tour. Mgmt. 2022, 53, 123–132.

- Amarnani, R.K.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Bordia, P.; Abbasi, A.A. Age as double-edged sword among victims of customer mistreatment: A self-esteem threat perspective. Hum. Resour. Mgmt. 2019, 58, 285–299.

- Miraglia, M.; Johns, G. The Social and Relational Dynamics of Absenteeism From Work: A Multilevel Review and Integration. Acad. Mgmt. Ann. 2021, 15, 37–67.

- Hsiao, A.; Ma, E.; Lloyd, K.; Reid, S. Organizational ethnic diversity’s influence on hotel employees’ satisfaction, commitment, and turnover intention Gender’s moderating role. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 76–108.

- Bani-Melhem, S.; Quratulain, S.; Al-Hawari, M.A. Customer incivility and frontline employees’ revenge intentions: Interaction effects of employee empowerment and turnover intentions. J. Hosp. Mktg. Mgmt. 2019, 29, 450–470.

- Wu, X.; Wang, J.; Ling, Q. Managing internal service quality in hotels: Determinants and implications. Tour. Mgmt. 2021, 86, 104329.

- Yin, J.; Ji, Y.; Ni, Y. Does “Nei Juan” affect “Tang Ping” for hotel employees? The moderating effect of effort-reward imbalance. Int. J. Hosp. Mgmt. 2023, 109, 103421.

- Guan, X.; Ahmad, N.; Sial, M.S.; Cherian, J.; Han, H. CSR and organizational performance: The role of pro-environmental behavior and personal values. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Mgmt. 2022, 30, 677–694.

- Malik, P.; Lenka, U. Exploring interventions to curb workplace deviance lessons from Air India. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 563–585.

- Li, J.; Wong, I.A.; Kim, W.G. Does mindfulness reduce emotional exhaustion? A multilevel analysis of emotional labor among casino employees. Int. J. Hosp. Mgmt. 2017, 64, 21–30.

- Panditharathne, P.N.K.W.; Chen, Z. An Integrative Review on the Research Progress of Mindfulness and Its Implications at the Workplace. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13852.

- Chen, H.; Eyoun, K. Do mindfulness and perceived organizational support work? Fear of COVID-19 on restaurant frontline employees’ job insecurity and emotional exhaustion. Int. J. Hosp. Mgmt. 2021, 94, 102850.

- Toniolo-Barrios, M.; Pitt, L. Mindfulness and the challenges of working from home in times of crisis. Bus. Horiz. 2021, 64, 189–197.

- Ben Haobin, Y.; Huiyue, Y.; Peng, L.; Fong, L.H.N. The impact of hotel servicescape on customer mindfulness and brand experience: The moderating role of length of stay. J. Hosp. Mktg. Mgmt. 2021, 30, 592–610.

- Yu, Y.; Xu, S.T.; Li, G. Abusive supervision and emotional labour on a daily basis: The role of employee mindfulness. Tour. Mgmt. 2023, 96, 104719.

- McCance, A.S.; Nye, C.D.; Wang, L.; Jones, K.S.; Chiu, C.-y. Alleviating the Burden of Emotional Labor. J. Manag. 2010, 39, 392–415.

- Yang, F.; Lu, M.; Huang, X. Customer mistreatment and employee well-being: A daily diary study of recovery mechanisms for frontline restaurant employees in a hotel. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102665.

- Huang, Y.-S.; Greenbaum, R.L.; Bonner, J.M.; Wang, C.S. Why sabotage customers who mistreat you? Activated hostility and subsequent devaluation of targets as a moral disengagement mechanism. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 495–510.

- Park, I.-J.; Kim, P.B.; Hai, S.; Dong, L. Relax from job, Don’t feel stress! The detrimental effects of job stress and buffering effects of coworker trust on burnout and turnover intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 559–568.

- Garcia, P.R.J.M.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Lu, V.N.; Amarnani, R.K.; Wang, L.; Capezio, A. Attributions of blame for customer mistreatment: Implications for employees’ service performance and customers’ negative word of mouth. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 203–213.

- Choi, C.H.; Kim, T.; Lee, G.; Lee, S.K. Testing the stressor–strain–outcome model of customer-related social stressors in predicting emotional exhaustion, customer orientation and service recovery performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 272–285.

- Torres, E.N.; van Niekerk, M.; Orlowski, M. Customer and employee incivility and its causal effects in the hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 48–66.

- Yu, H.; Lee, L.; Popa, I.; Madera, J.M. Should I leave this industry The role of stress and negative emotions in response to an industry negative work event. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102843.

- Simillidou, A.; Christofi, M.; Glyptis, L.; Papatheodorou, A.; Vrontis, D. Engaging in emotional labour when facing customer mistreatment in hospitality. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 429–443.

- Frey-Cordes, R.; Eilert, M.; Büttgen, M. Eye for an eye? Frontline service employee reactions to customer incivility. J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 34, 939–953.

- Neri, A.C.; Dupin, P.; Sanchez, L.E. A pressure–state–response approach to cumulative impact assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 288–298.

- Salemi, M.; Jozi, S.A.; Malmasi, S.; Rezaian, S. Conceptual framework for evaluation of ecotourism carrying capacity for sustainable development of Karkheh protected area, Iran. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 354–366.

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.-M.; Hwang, H. Impacts of customer incivility and abusive supervision on employee performance: A comparative study of the pre- and post-COVID-19 periods. Serv. Bus. 2021, 16, 309–330.

- Ersoy, A.; Mahmood, Z.; Sharif, S.; Ersoy, N.; Ehtiyar, R. Exploring the Associations between Social Support, Perceived Uncertainty, Job Stress, and Emotional Exhaustion during the COVID-19 Crisis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2150.

- Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S.; Orús, C. Integrating virtual reality devices into the body: Effects of technological embodiment on customer engagement and behavioral intentions toward the destination. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 847–863.

- Yin, J.; Cheng, Y.; Bi, Y.; Ni, Y. Tourists perceived crowding and destination attractiveness: The moderating effects of perceived risk and experience quality. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100489.

- Jung, H.-S.; Yoon, H.-H. The Effect of Social Undermining on Employees’ Emotional Exhaustion and Procrastination Behavior in Deluxe Hotels: Moderating Role of Positive Psychological Capital. Sustainability 2022, 14, 931.

- Hur, W.-M.; Moon, T.W.; Han, S.-J. The effect of customer incivility on service employees’ customer orientation through double-mediation of surface acting and emotional exhaustion. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2015, 25, 394–413.

- Lee, R.; Mai, K.M.; Qiu, F.; Ilies, R.; Tang, P.M. Are you too happy to serve others? When and why positive affect makes customer mistreatment experience feel worse. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2022, 172, 104188.

- Trepanier, S.; Henderson, R.; Waghray, A. A Health Care System’s Approach to Support Nursing Leaders in Mitigating Burnout Amid a COVID-19 World Pandemic. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2022, 46, 52–59.

- Cho, J.-E.; Choi, H.S.C.; Lee, W.J. An Empirical Investigation of the Relationship Between Role Stressors, Emotional Exhaustion and Turnover Intention in the Airline Industry. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 1023–1043.

- McKenna, J.; Jeske, D. Ethical leadership and decision authority effects on nurses’ engagement, exhaustion, and turnover intention. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 77, 198–206.

- Alola, U.V.; Olugbade, O.A.; Avci, T.; Öztüren, A. Customer incivility and employees’ outcomes in the hotel: Testing the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Tour. Mgmt. Perspect. 2019, 29, 9–17.

- Bentein, K.; Guerrero, S.; Jourdain, G.; Chênevert, D. Investigating occupational disidentification: A resource loss perspective. J. Manag. Psychol. 2017, 32, 530–546.

- Peltokorpi, V.; Allen, D.G. Job embeddedness and voluntary turnover in the face of job insecurity. J. Organ. Behav. 2023.

- Lea, J.; Doherty, I.; Reede, L.; Mahoney, C.B. Predictors of burnout, job satisfaction, and turnover among CRNAs during COVID-19 surging. AANA J. 2022, 90, 141–147.

- Diefendorff, J.M.; Gabriel, A.S.; Nolan, M.T.; Yang, J. Emotion regulation in the context of customer mistreatment and felt affect: An event-based profile approach. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 104, 965–983.

- Raza, B.; St-Onge, S.; Ali, M. Consumer aggression and frontline employees’ turnover intention: The role of job anxiety, organizational support, and obligation feeling. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 97, 103015.

- Peng, J.; Yang, X.; Guan, X.; Zhou, L.; Huan, T.-C. Will catering employees’ job dissatisfaction lead to brand sabotage behavior? A study based on conservation of resources and complexity theories. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 1882–1905.

- Koon, V.-Y.; Pun, P.-Y. The Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion and Job Satisfaction on the Relationship Between Job Demands and Instigated Workplace Incivility. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2017, 54, 187–207.

- Jahanzeb, S.; Fatima, T. How Workplace Ostracism Influences Interpersonal Deviance: The Mediating Role of Defensive Silence and Emotional Exhaustion. J. Bus. Psychol. 2017, 33, 779–791.

- Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Xie, J. Does customer mistreatment hinder employees from going the extra mile? The mixed blessing of being conscientious. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103155.

- Abdalla, M.d.J.; Said, H.; Ali, L.; Ali, F.; Chen, X. COVID-19 and unpaid leave: Impacts of psychological contract breach on organizational distrust and turnover intention: Mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100854.

- Lee, Y.; Kim, I. Investigating key innovation capabilities fostering visitors’ mindfulness and its consequences in the food exposition environment. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 803–818.

- Moscardo, G. Exploring mindfulness and stories in tourist experiences. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 11, 111–124.

- Chan, E.Y. Mindfulness promotes sustainable tourism: The case of Uluru. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 22, 1526–1530.

- Hyland, P.K.; Lee, R.A.; Mills, M.J. Mindfulness at Work: A New Approach to Improving Individual and Organizational Performance. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 576–602.

- Walsh, M.M.; Arnold, K.A. The bright and dark sides of employee mindfulness: Leadership style and employee well-being. Stress Health 2020, 36, 287–298.

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Breazeale, M.; Radic, A. Happiness with rural experience: Exploring the role of tourist mindfulness as a moderator. J. Vacat. Mark. 2019, 25, 279–300.

- Fan, L.; Zhou, X.; Ren, J.; Ma, J.; Yang, Y.; Shao, W. A self-regulatory perspective on the link between customer mistreatment and employees’ displaced workplace deviance: The buffering role of mindfulness. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2704–2725.

- Op den Kamp, E.M.; Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Creating a creative state of mind: Promoting creativity through proactive vitality management and mindfulness. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 72, 743–768.

- Hahn, A.M.; Simons, R.M.; Simons, J.S.; Welker, L.E. Prediction of verbal and physical aggression among young adults: A path analysis of alexithymia, impulsivity, and aggression. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 273, 653–656.

- Anasori, E.; Bayighomog, S.W.; Tanova, C. Workplace bullying, psychological distress, resilience, mindfulness, and emotional exhaustion. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 40, 65–89.

- Jang, J.; Jo, W.; Kim, J.S. Can employee workplace mindfulness counteract the indirect effects of customer incivility on proactive service performance through work engagement? A moderated mediation model. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 812–829.

More