You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Lindsay Dong and Version 3 by Lindsay Dong.

Low back pain (LBP) is a health problem that affects 70–80% of the population in Western countries. Because of the biomechanical relationship between the lumbar region and the hip, it is thought that strengthening the muscles of this joint could improve the symptoms of people with LBP. Participants who performed hip strengthening exercises had significantly improved in pain and disability.

- low back pain

- hip

- strengthening

- treatment

- pain

1. Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is an increasingly common condition worldwide, but in practical terms it is estimated that 70–80% of the population from countries of the Western world will suffer LBP at some point in their lives, especially affecting women over 40 years old [1][2][1,2]. This makes LBP the second most frequent chronic skeletal muscle pathology after osteoarthritis [1]. The history of LBP is the most consistent with and the main cause of general mobility restriction, long-term disability, and decreased quality of life (QoL); this is because the pain does not specifically limit the movement of a joint, but rather the pain is the cause of limiting general mobility in the daily life of patients [1][3][1,3]. It is noteworthy that the overall healthcare cost analysis of LBP is estimated in the range of USD 100 billion per year in the United States of America, including direct tangible costs, indirect costs of labor, productivity slowdowns, and monetary compensations [4]. Although most episodes of LBP usually resolve spontaneously a few days after their onset, a substantial proportion of patients, approximately 5–10% of the population, will develop chronic (duration > 3 months) or recurrent pain [1][5][1,5]. In 85% of cases, LBP is considered as non-specific pain, which means that no structural change, no inflammation, and no specific disease can be found as its cause [6]. This type of LBP is often associated with psychosocial factors and abnormal pain-coping behaviors [1].

One of the main problems of low back pain is the variety of treatments which occasionally are not harmonized with what has been reported by scientific evidence, worsening the results, chronifying pain, and substantially increasing healthcare costs [7][8][7,8]. During the acute phase (first 2–3 days), low back pain must be treated with rest and drugs (anti-inflammatory and/or analgesics), but if the pain persists, maintaining rest favors chronification [1]. For this reason, therapeutic exercise could currently be established as the most useful intervention in the treatment of LBP [9]. Therapeutic exercise in LBP would relieve pain, improve functionality, and reduce the risk of recurrence [9]. It is necessary to consider the entire spectrum of different exercise therapies, including motor control exercises, balance, aerobic training, stretching, and muscle strengthening [9].

The lumbar spine is biomechanically connected to the pelvic and hip joint, making it difficult to determine the provenance of symptoms in clinical practice [10]. The normal range of movement (ROM) of the hip is often altered in patients with LBP, making it impossible to correctly transmit the load from the lower limb (LL) to the trunk [11][12][11,12]. This is usually due to shortening of the flexor muscles, which limits coxofemoral extension and therefore increases lumbar extension, leading to lordosis [11][12][11,12]. On the other hand, it is common to find strength deficiency of the hip abductor and extensor muscles in patients suffering from LBP [12][13][14][12,13,14]. This shortage is usually compensated by over use of the hamstring muscles, which can lead to their curtailment and increased compensatory movements of the spine [12]. For this reason, studies and guidelines have recently begun to include hip strengthening exercises as part of the treatment of low back pain. [14]. In this sense, de Jesus et al. [14] has described that the inclusion of specific hip strengthening exercises in conventional rehabilitation therapy for low back pain attenuates painful symptoms and disability.

2. Hip Muscle Strengthening Exercises and Low Back Pain

According to the World Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), pain is considered “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” [15][25]. Pain is subjective and should not always be eliminated, as it acts as a defense mechanism, protecting the body from dangerous situations. However, sometimes pain becomes a source of suffering, especially when appearing in the absence of tissue damage, frequently due to psychological disorders [15][16][25,26]. For its part, disability related to LBP makes it difficult to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and work tasks [17][27]. Additionally, LBP can lead the individual to social isolation and to avoid daily activities, reducing their self-efficacy and increasing the chances of developing depressive symptoms and disability [18][28]. In his way, aerobic exercise programs can produce a substantial improvement in mood and reduce depression in chronically ill patients [19][29]. Five of the studies [20][21][22][23][24][18,19,21,23,24] found statistically significant improvements (p < 0.05) in both pain and disability compared to the CG and seven [20][21][22][23][24][25][26][18,19,20,21,22,23,24] in the IG compared to baseline. This incongruity observed in results is likely due to the intensity, frequency, and duration of the interventions. The number of weekly sessions carried out in the study by Fukuda et al. [25][20] was two, and Kendall et al. [26][22] indicate that only one face-to-face session was given weekly, without specifying the number of weekly sessions at home, the duration of the sessions, or details about the volume and intensity (number of exercises, series, repetitions, rest times, etc.) of the same. This differs with the number of weekly sessions carried out in the interventions of the studies that obtained improvements in comparation to the CG, ranging from three to seven [20][21][22][23][24][18,19,21,23,24]. Additionally, the duration of treatment was shorter. Fukuda et al. [22][21] conducted a 5-week intervention and Kendall et al. [26][22] a 6-week intervention, while the duration in the rest of the studies was 6 to 8 weeks [20][21][22][23][24][18,19,21,23,24].

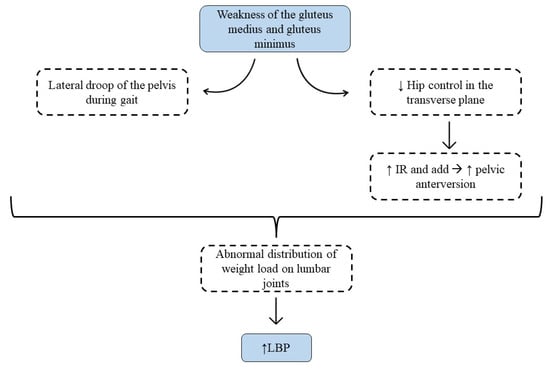

Although the mechanism by which HMS exercises reduce pain and disability levels is not well understood, it may be due to the increase in pelvic stability provided by strengthening of the gluteal muscles [14][27][14,30]. The gluteus medius and minimus are responsible for controlling the position and stability of both the hip and the pelvis, so their weakness can lead to biomechanical changes in the coxolumbopelvic complex, contributing to LBP [27][30]. Mainly it will lead to the lateral descent of the pelvis while walking, which is known as the Trendelenburg sign. This will cause an abnormal distribution of weight load on the intervertebral discs and lumbar joints [27][30]. Additionally, gluteal weakness can lead to less control of the hip in the transverse plane, increasing internal rotation and adduction of the femur, which leads to an increase in pelvic anteversion and again results in abnormal load distribution at the lumbar level [11] (Figure 1). However, for the correct functioning of the coxolumbopelvic complex, not only an adequate level of force is necessary, but it is also important that the hip and lumbar ROM are maintained [11]. Techniques to increase ROM such as manual therapy or stretching could be useful adjuncts to improve pain and disability in patients with LBP [20][23][24][18,23,24]. In this sense, Kim and Yim [23] divided the IG into two: one performed static stretching of the hip muscles and the other HMS, and both found statistically significant improvements (p < 0.05) with respect to the CG and the baseline, with no differences between the two IGs in count pain and disability. However, they found statistically significant increases (p < 0.05) compared to the CG in QoL and lumbar stability in the IG who performed stretching. These increases were not observed in the IG with HMS exercises, demonstrating the importance of preserving the lumbar and pelvic–femoral ROM in the treatment of LBP.

Figure 1. Description of the mechanism for how gluteal weakness increases low back pain.

3. Potential Applications

Considering the different protocols and results, some scholars developed a therapeutic exercise intervention protocol with the aim of guiding clinical practice (Table 1). The training sessions should be structured in three parts, first with a warm-up with joint mobility exercises and muscle activation. The main part is where the HMS exercises are carried out, such as squats, Monster Walk, gluteal kick, lateral clam, gluteal bridge, and finally returning through relaxation exercises towards a calmer state. Importantly, static stretching and manual therapy of the coxofemoral joint are crucial through these sessions. Therefore, it would fulfill the key points of LBP treatment that it has developed throughout the discussion, specifically the HMS of the gluteus and the maintenance of the hip ROM. At the same time, it would also be interesting to include exercises to strengthen lumbar muscles and motor control, in addition to manual therapy techniques specifically targeting the lumbar spine. In relation to the workload, two to three series of 8–12 repetitions per exercise should be performed with a minute of rest between series and an intensity of 75–80% of one maximum repetition (RM). The duration of the sessions is approximately 60 min and may be conducted in 3–4 weekly sessions.

Table 1. Hip muscle strengthening intervention protocol in patients with LBP.

| Warm-Up | Central Part | Return to Calm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exercises | Joint mobility Muscular activation |

HM strengthening: Squat Monster Walk Quadruped hip extension Clam in side lying Bridge |

Relax Static stretch Manual therapy |

| Intensity | Minimum | 75–80% RM | |

| Volume | 2–3 sets/8–12 reps for ex. 1 min rest |

||

| Time | 5–10 min | 45–50 min | 5–10 min |

| Frequency | 3–4 days/week, with 1–2 days of rest between sessions | ||

| Observations | The volume and intensity should be increased as the patient improves, increasing the number of repetitions and/or loads (elastic resistance or weight) | ||

| Abbreviations | RM: maximal repetition; reps: repetitions | ||