You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 1 by Malgorzata Mrugacz.

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) is the second most common retinal disorder. In comparison to diabetic retinopathy or age-related macular degeneration, RVO is usually an unexpected event that carries a greater psychological impact.

- eye

- retinal vein occlusion

- diet

- lifestyle

1. Introduction

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) ranks as the second most prevalent retinal disorder, second to diabetic retinopathy, with an estimated incidence of 0.3% to 2.3% depending on ethnicity, and can lead to blindness of a vascular origin [1]. The retinal vasculature gives a non-invasive in vivo insight into the state of the human microcirculation [2]. It is believed that the pathogenesis of retinal vein occlusion is caused by mechanical compression by atherosclerosis of the retinal artery. The central retinal artery and vein share a common adventitious sheath. Changes in the arterial wall associated with atherosclerosis or hypertension increase its stiffness which translates into increased impact on the central retinal vein, leading to turbulent blood flow in its lumen. This cascade of events leads to endothelial damage and ultimately leads to hypercoagulability and occlusion of the vessel [3]. Depending on the anatomical location of the thrombus, the following types are distinguished: central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), superior or inferior retinal vein occlusion (hemi-CRVO), and branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO). Typical risk factors for RVO include advanced age, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and glaucoma [4]. In the younger population, special attention is paid to lipid disorders of the blood as the main risk factor [5].

There is ample evidence that cytokines and chemokines contained in the vitreous body are correlated with the occurrence of RVO, especially the interleukin family, VEGF, MMP, LPA-ATX and PDGF [4]. The interleukin family is pro-inflammatory, causing ischemia and macular edema secondary to RVO, and the most important in this disease include IL-6, IL-8, IL-17 and IL-18, which trigger STAT3, MAPK, NF-κB, VEGF pathways and provoke ROS. VEGF inhibits occludin by damaging the basement membrane of endothelial cells and activates MMP-9 to destroy blood–retinal barriers (BRB) and induces ICAM-1 causing leukocyte stasis. VEGF also works by activating the NOX1 and NOX4 proteins, which are dominant in ROS production in RVO. MMP-2 and MMP-7 are involved in the migration of vascular endothelial cells. The LPA-ATX signaling pathway may mediate inflammation in RVO as it activates IL-6, IL-8, VEGF and MMP-9. PDGF-A potentiates VEGF to induce neovascularization. An interesting study was presented by Takuma Neo et al., who used the rabbit retinal vein occlusion model in order to analyze ischemia-induced changes in gene expression profiles [6]. The study revealed that angiogenic regulators Dcn and Mmp1 and the pro-inflammatory factors Mmp12 and Cxcl13 were significantly elevated in RVO retinas. In total, they analyzed 387 genes with more than a 2-fold difference between RVO and controls (upregulated: 333 genes, downregulated: 54 genes). What is more, they confirmed that JAK-STAT, TNFα and NF-κB pathways likely contribute to rabbit RVO pathology and potentially human retinal ischemic disease.

Given the intricate nature of risk factors and their interplay in RVO, it is crucial to identify the most important predictors of the disease early, as well as to introduce appropriate prophylaxis. A well-known part of the Hippocratic oath states–prevention is better than cure. This holds particular significance in thrombotic disorders affecting the venous vascular system of the eye, as they can result in abrupt and painless vision deterioration or visual field abnormalities, potentially leading to complete blindness in severe cases [7]. The main complications of RVO are macular edema, neovascular glaucoma, and hemorrhage into the vitreous chamber [7]. The treatment of complications associated with RVO consists primarily of the intravitreal administration of anti-VEGF preparations in the event of macular edema and photocoagulation of the entire retina in cases of iris neovascularization [8,9][8][9]. It has been proven that during RVO, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is the main cytokine inducing ischemia and neovascularization; therefore, intravitreal anti-VEGF in the event of macular edema following retinal vein occlusion is the first line of treatment [1]. Aflibercept (EYLEA) is a fusion protein that binds VEGF-A, VEGF-B and placental growth factor (PIGF) with a greater affinity than the body’s native receptors. Ranibizumab (Lucentis) is a recombinant humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody fragment that binds to and inhibits only VEGF-A. Bevacizumab (Avastin) is a humanized antibody that binds all subtypes of VEGF-A. The recommended dose for aflibercept is 2 mg (0.05 mL), for bevacizumab it is 1.25 mg (0.05 mL) and for ranibizumab it is 0.5 mg (0.05 mL) administered by intravitreal injection once every 4 weeks. After the first several injections, some patients continue monthly treatment, some patient are treated at increasing intervals and some patients are checked monthly and treated as needed. Faricimab (Vabysmo) is a promising bispecific drug targeting VEGF-A and the Ang-Tie/pathway [10]. It is a combined-mechanism medication with simultaneous and independent binding on both VEGF-A and angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2). It is believed to have a more lasting effect than previous anti-VEGF drugs in clinical trials. The FDA approved Vabysmo for the treatment of diabetic macular edema and neovascular age-related macular degeneration on January 2022. Another option to deliver effective anti-VEGF doses over a longer period of time is to use a slow-release intraocular device, such as a PDS device [10]. Patients who do not respond to anti-VEGF preparations are recommended to implement intravitreal steroid injection–triamcinolone or dexamethasone implant (DEX, Ozurdex) which reduce pathologically increased capillary permeability and inhibit the expression of cytokines and chemokines. Another method of treating macular edema is focal laser or grid laser which has now lost its importance because of intravitreal drug injections. In patients with ischemic RVO, panretinal laser photocoagulation (PRP) is recommended for treatment of secondary neovascular complications. The use of systemic recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA), radial optic neurotomy, chorioretinal anastomosis and arteriovenous sheathotomy are extremely rarely used methods due to possible complications such as sudden hemorrhage, visual-field defects or retinal detachment [1]. Pars plana vitrectomy is considered in the presence of attached posterior hyaloids accompanied by persistent macular edema in CRVO. The recommended treatment methods are, unfortunately, associated with regular, lengthy visits to ophthalmological treatment facilities, which for people who are professionally active means exclusion from the labor market, and for the elderly and dependent people, family involvement in the treatment process. These and other disturbances of the quality of life of patients with RVO, such as fear of the second eye being affected by the disease process, fear of not improving after injections, and fear of the future, were demonstrated in the work of Prem Senthil et al. [11].

2. Plant-Based Diets Reducing the Main RVO Risk Factors: Hypertension, Hyperlipidemia, and Diabetes

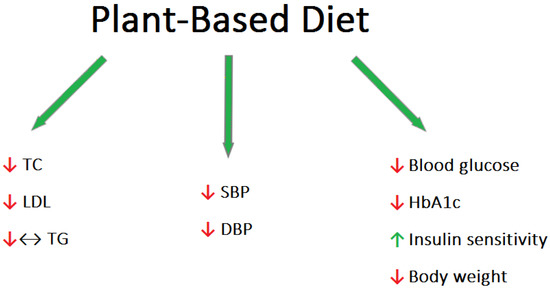

The essential role of food ingredients in human physiology has been widely recognized for a considerable period of time. However, it has only recently been recognized that many micronutrients have a profound influence on human health and disease risk. Several dietary factors possess the remarkable capability of modifying the expression of regulatory genes involved in human metabolism [12]. These genes govern crucial processes like cell growth, programmed cell death, and immune system response. Effective control of these processes is critical for preventing various human ailments, including cancer, autoimmune disorders, and inflammatory conditions [13]. The most widely accepted dietary patterns in Western countries include the plant-based diet (PBD), the Mediterranean diet (MD), the Paleolithic diet, low-carbohydrate diets, and low-fat diets. In particular, the plant-based diet is growing in popularity as the healthiest diet. The most important concern with this nutritional approach is the risk of developing nutritional deficiencies in protein, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin B12, iron, zinc, iodine, vitamin D, and calcium. However, as a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, the PBD is high in fiber, omega-6 fatty acids, antioxidants, and phytochemicals [14]. Various types of diets can be distinguished among the PBD. Vegetarians can be categorized into different groups based on their dietary preferences. Lacto-ovo vegetarians abstain from consuming meat but include dairy products, eggs, and other animal-derived foods in their diet. Lacto-vegetarians, on the other hand, exclude eggs while still consuming dairy products. Ovo-vegetarians exclude dairy products but include eggs as part of their dietary choices. The vegan model excludes all foods of animal origin. Patients following a plant-based diet tended to have lower blood pressure (BP), body mass index (BMI), and lower total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglycerides (TG), and blood glucose levels compared to omnivorous people [15] (Figure 1). High blood pressure (BP) is recognized as a significant modifiable cardiovascular risk factor [16]. Dietary patterns play a crucial role in both preventing and managing this condition. By adopting appropriate dietary choices, it is possible to delay the onset of high blood pressure and mitigate its effects. It should be characterized by a low intake of saturated fatty acids, a high intake of fruits and vegetables, limiting the amount of foods with high salt content, and limiting the consumption of alcohol. A meta-analysis of 32 observational studies with 604 participants found an association between vegetarian diets and average reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure of 6.9 mmHg and 4.7 mmHg, respectively [17]. Epidemiological research conducted in Western countries has revealed a notable occurrence of hypercholesterolemia, accompanied by a high frequency of cardiovascular disease and associated mortality [18]. Clinical trials have further demonstrated that even a modest reduction of 1% in LDL cholesterol levels can lead to a corresponding decrease of approximately 1% in the risk of major cardiac events, such as heart attacks and strokes [19]. Lifestyle changes, particularly diet and exercise, have been shown to lower LDL levels by up to 30–40% in people at risk for cardiovascular disease, which may play a significant role in preventing and possibly treating this group of diseases [20]. Animal fats such as meat, butter, whole dairy products, as well as tropical coconut and palm oils are typically high in saturated fatty acids (SFAs). In contrast, vegetable fats, consisting mainly of vegetable oils, are generally rich in unsaturated fatty acids. The latter can be monounsaturated (MUFA) or polyunsaturated (PUFA). Replacing SFA with unsaturated fatty acids (especially PUFA) reduces LDL-C without affecting HDL-C and TG [21]. Additionally, the PBD is characterized by the presence of phytosterols (found in all products of plant origin), which reduce the absorption of cholesterol [22]. Wang et al. conducted a meta-analysis showing that PBD significantly lowered total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol; however, no effect on triglyceride levels was observed [23]. Identical results were obtained in a meta-analysis evaluating 39 studies [24]. However, there are studies suggesting that TG concentrations are significantly lower in vegetarians than in omnivores [25]. Interestingly, dietary fiber is inversely related to TG concentrations, as demonstrated by Hannon et al. in a crossover study of 117 participants who experienced a reduction in TG levels after 7 days of treatment by means of a controlled diet [26]. There is strong evidence suggesting that vegetarian and particularly vegan dietary patterns have a positive impact on fasting and postprandial blood lipid levels, comparable to the effects achieved through conventional therapeutic diets and statin treatment [23]. Diabetes is a disease that is increasing in prevalence, carrying a significant health and economic burden [27]. Therefore, preventive measures aimed at stopping the “diabetes epidemic” are desirable in public healthcare. The incidence of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) appears to be relatively low among those following a PBD [28]. Vegetarian diets have been shown in several clinical studies to be helpful in the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes [29]. Scientific studies have demonstrated a decrease in plasma glucose levels, and, thus, a dramatic reduction in the use of antidiabetic drugs in response to the adaptation of a plant-based diet [30]. A 2014 meta-analysis found that a plant-based diet significantly improved blood sugar control. This conclusion was inferred from lowering the plasma glycated hemoglobin in T2DM patients [31]. One of the mechanisms possibly responsible for the improvement in glycemic control is the increased insulin sensitivity that is achieved by the consumption of soybeans (a common protein replacement in a plant-based diet that contains high amounts of lysine, leucine, phenylalanine, phosphate, and calcium) [32]. Cereals reduce the risk of diabetes because they are rich in magnesium, a deficiency of which impairs the signaling of the insulin pathway [33]. The protective antidiabetic effect of PBD also originates from the lack of fats of animal origin and the increased consumption of foods with a low glycemic index [34]. It is important to remember that the reduction in calorie intake associated with meat-free diets can result in weight loss, which is a widely recognized factor that significantly affects the control of blood sugar levels [31].References

- Ho, M.; Liu, D.T.L.; Lam, D.S.C.; Jonas, J.B. Retinal Vein Occlusions, from Basics to the Latest Treatment. Retina 2016, 36, 432–448.

- Sun, C.; Wang, J.J.; Mackey, D.A.; Wong, T.Y. Retinal Vascular Caliber: Systemic, Environmental, and Genetic Associations. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2009, 54, 74–95.

- Green, W.R.; Chan, C.C.; Hutchins, G.M.; Terry, J.M. Central Retinal Vein Occlusion: A Prospective Histopathologic Study of 29 Eyes in 28 Cases. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 1981, 79, 371–422.

- Tang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Wu, H. Review: The Development of Risk Factors and Cytokines in Retinal Vein Occlusion. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 910600.

- Chen, T.Y.; Uppuluri, A.; Zarbin, M.A.; Bhagat, N. Risk Factors for Central Retinal Vein Occlusion in Young Adults. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 31, 2546–2555.

- Neo, T.; Gozawa, M.; Takamura, Y.; Inatani, M.; Oki, M. Gene Expression Profile Analysis of the Rabbit Retinal Vein Occlusion Model. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236928.

- McIntosh, R.L.; Rogers, S.L.; Lim, L.; Cheung, N.; Wang, J.J.; Mitchell, P.; Kowalski, J.W.; Nguyen, H.P.; Wong, T.Y. Natural History of Central Retinal Vein Occlusion: An Evidence-Based Systematic Review. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 1113–1123.e15.

- Braithwaite, T.; Nanji, A.A.; Lindsley, K.; Greenberg, P.B. Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor for Macular Oedema Secondary to Central Retinal Vein Occlusion. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 5, CD007325.

- Hayreh, S.S. Photocoagulation for Retinal Vein Occlusion. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2021, 85, 100964.

- Ghanchi, F.; Bourne, R.; Downes, S.M.; Gale, R.; Rennie, C.; Tapply, I.; Sivaprasad, S. An Update on Long-Acting Therapies in Chronic Sight-Threatening Eye Diseases of the Posterior Segment: AMD, DMO, RVO, Uveitis and Glaucoma. Eye 2022, 36, 1154–1167.

- Senthil, M.P.; Khadka, J.; Gilhotra, J.S.; Simon, S.; Fenwick, E.K.; Lamoureux, E.; Pesudovs, K. Understanding Quality of Life Impact in People with Retinal Vein Occlusion: A Qualitative Inquiry. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2019, 102, 406–411.

- Demmig-Adams, B.; Adams, R.B. Eye Nutrition in Context: Mechanisms, Implementation, and Future Directions. Nutrients 2013, 5, 2483–2501.

- Lavrovsky, Y.; Chatterjee, B.; Clark, R.A.; Roy, A.K. Role of Redox-Regulated Transcription Factors in Inflammation, Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Exp. Gerontol. 2000, 35, 521–532.

- Bakaloudi, D.R.; Halloran, A.; Rippin, H.L.; Oikonomidou, A.C.; Dardavesis, T.I.; Williams, J.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Breda, J.; Chourdakis, M. Intake and Adequacy of the Vegan Diet. A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3503–3521.

- Kahleova, H.; Levin, S.; Barnard, N. Cardio-Metabolic Benefits of Plant-Based Diets. Nutrients 2017, 9, 848.

- GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1659–1724.

- Yokoyama, Y.; Nishimura, K.; Barnard, N.D.; Takegami, M.; Watanabe, M.; Sekikawa, A.; Okamura, T.; Miyamoto, Y. Vegetarian Diets and Blood Pressure. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 577–587.

- Carroll, M.D.; Lacher, D.A.; Sorlie, P.D.; Cleeman, J.I.; Gordon, D.J.; Wolz, M.; Grundy, S.M.; Johnson, C.L. Trends in Serum Lipids and Lipoproteins of Adults, 1960–2002. JAMA 2005, 294, 1773–1781.

- Grundy, S.M.; Cleeman, J.I.; Merz, C.N.B.; Brewer, H.B.; Clark, L.T.; Hunninghake, D.B.; Pasternak, R.C.; Smith, S.C.; Stone, N.J. Implications of Recent Clinical Trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 44, 720–732.

- Howard, B.V.; Roman, M.J.; Devereux, R.B.; Fleg, J.L.; Galloway, J.M.; Henderson, J.A.; Howard, W.J.; Lee, E.T.; Mete, M.; Poolaw, B.; et al. Effect of Lower Targets for Blood Pressure and LDL Cholesterol on Atherosclerosis in Diabetes. JAMA 2008, 299, 1678–1689.

- Mensink, R.P.; Katan, M.B. Effect of dietary fatty acids on serum lipids and lipoproteins. A meta-analysis of 27 trials. Arterioscler. Thromb. 1992, 12, 911–919.

- Gylling, H.; Plat, J.; Turley, S.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Ellegård, L.; Jessup, W.; Jones, P.J.H.; Lütjohann, D.; Mӓrz, W.; Masana, L.; et al. Plant sterols and plant stanols in the management of dyslipidaemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2014, 232, 346–360.

- Wang, F.; Zheng, J.; Yang, B.; Jiang, J.; Fu, Y.; Li, D. Effects of Vegetarian Diets on Blood Lipids: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, e002408.

- Yokoyama, Y.; Levin, S.M.; Barnard, N.D. Association between plant-based diets and plasma lipids: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 683–698.

- De Biase, S.G.; Fernandes, S.F.C.; Gianini, R.J.; Duarte, J.L.G. Vegetarian diet and cholesterol and triglycerides levels. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2007, 88, 35–39.

- Hannon, B.A.; Thompson, S.V.; Edwards, C.G.; Skinner, S.K.; Niemiro, G.M.; Burd, N.A.; Holscher, H.D.; Teran-Garcia, M.; Khan, N.A. Dietary Fiber Is Independently Related to Blood Triglycerides Among Adults with Overweight and Obesity. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2018, 3, nzy094.

- Dall, T.M.; Yang, W.; Gillespie, K.; Mocarski, M.; Byrne, E.; Cintina, I.; Beronja, K.; Semilla, A.P.; Iacobucci, W.; Hogan, P.F. The Economic Burden of Elevated Blood Glucose Levels in 2017: Diagnosed and Undiagnosed Diabetes, Gestational Diabetes Mellitus, and Prediabetes. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1661–1668.

- McMacken, M.; Shah, S. A plant-based diet for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 342–354.

- Marrone, G.; Guerriero, C.; Palazzetti, D.; Lido, P.; Marolla, A.; Di Daniele, F.; Noce, A. Vegan Diet Health Benefits in Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients 2021, 13, 817.

- Toumpanakis, A.; Turnbull, T.; Alba-Barba, I. Effectiveness of plant-based diets in promoting well-being in the management of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2018, 6, e000534.

- Yokoyama, Y.; Barnard, N.D.; Levin, S.M.; Watanabe, M. Vegetarian diets and glycemic control in diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2014, 4, 373–382.

- van Nielen, M.; Feskens, J.E.; Rietman, A.; Siebelink, E.; Mensink, M. Partly Replacing Meat Protein with Soy Protein Alters Insulin Resistance and Blood Lipids in Postmenopausal Women with Abdominal Obesity. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 1423–1429.

- Suárez, A.; Pulido, N.; Casla, A.; Casanova, B.; Arrieta, F.J.; Rovira, A. Impaired tyrosine-kinase activity of muscle insulin receptors from hypomagnesaemic rats. Diabetologia 1995, 38, 1262–1270.

- Sahyoun, N.R.; Anderson, A.L.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Lee, J.S.; Sellmeyer, D.E.; Harris, T.B. Dietary glycemic index and glycemic load and the risk of type 2 diabetes in older adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 126–131.

More