Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jason Zhu and Version 1 by Benoît Lenzen.

The interest in life skills development through sport and physical education (PE) has been perceptible for the past. Life skills have been defined by the World Health Organisation as “abilities for adaptative and positive behaviour, that enable individuals to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life”and paired to reveal five main life skills “areas”: decision making—problem solving; creative thinking—critical thinking; communication—interpersonal relationships; self-awareness—empathy; coping with emotions—coping with stress.

- physical education

- life skills

- teaching traditions

1. Introduction

The interest in life skills development through sport and physical education (PE) has been perceptible for the last twenty years [1,2,3][1][2][3]. Life skills have been defined by the World Health Organisation as “abilities for adaptative and positive behaviour, that enable individuals to deal effectively with the demands and challenges of everyday life” [4] (p. 1) and paired to reveal five main life skills “areas”: decision making—problem solving; creative thinking—critical thinking; communication—interpersonal relationships; self-awareness—empathy; coping with emotions—coping with stress. However, other international organisations such as the UNICEF [5] as well as several academics [2,6][2][6] agree on the difficulty of defining them:

While the concept embraces a wide range of skills and has a virtue of linking personal and social skills to the realities of everyday life, it suffers because it is difficult, and potentially contentious, to determine which skills are relevant for life and which are not. This is problematic because if all skills are indeed relevant for life, then the concept has little utility.[5] (p. 8)

Moreover, when referring to personal and social development, different terms are used interchangeably to describe similar concepts [6[6][7],7], e.g., life skills, psychosocial skills, transferable skills, soft skills, socio-emotional skills, and twenty-first century skills. Despite these debates on what life skills are and how they are labelled, educational and governmental organisations have highlighted that these skills are important for adolescents’ health, well-being, and their educational and occupational success [3], encouraging policy makers to integrate life skills education into the school curriculum. Results of a systematic review analysing evaluated school-based life skills programmes regarding age-specific targeted life skills showed that programmes were mostly implemented in adolescence, and that the targeted life skills shifted from a more behavioural-affective focus in childhood to a broader set of life skills targeted in adolescence [7].

Sports and PE are seen as settings that can enhance participants’ life skills [3,8][3][8]. The potential of these settings to teach life skills is grounded on several reasons [6,8,9][6][8][9]: sports and PE are social in nature; there is an apparent similarity between the mental skills needed for successful performance in sports and in non-sports domains; many of the skills learned in sports and PE settings can be transferred to other life domains; sports make up a setting that emphasises training and performance, similar to school and work; sport skills and life skills are learned in the same way, i.e., through demonstration, modelling and practice; sports is a significant factor in the development of adolescents’ self-esteem and perception of competence; there is an apparent conceptual similarity between the philosophy of Olympism and the notion of teaching transferable skills through sports. Different teaching approaches (e.g., sports education, cooperative learning) have been shown to help PE students develop their teamwork, communication, problem solving and decision making, leadership, and social skills [3]. A review of 88 studies using several study designs, methods, and instruments to investigate a variety of concepts related to personal and social development within the context of PE and sports led to the identification of 11 themes by grouping similar concepts [6]: work ethic; control and management; goal-setting; decision-making; problem-solving; responsibility; leadership; cooperation; meeting people and making friends; communication; and prosocial behaviour. Transferability is central to the definition of life skills (WHO, UNICEF). However, the transfer of life skills from the sports or PE environment to other areas of life has yet to be operationally defined and addressed [8,10,11,12,13][8][10][11][12][13]. Evidence from the recent literature in sport pedagogy or psychology shows that:

-

The individual learner is the critical agent in the transfer process, which occurs when they interact with potential transfer environments [11];

Three types of life skills programmes developed for sports and PE have been distinguished [8]: (a) programmes that teach life skills in classroom settings using sport metaphors (which weis referrred to as isolated); (b) programmes teaching life skills in youth sport settings in addition to sport skills (which weis referred to as juxtaposed); and (c) programmes teaching life skills within the practice of PE and sports at the same time with physical skills (which we referis referred to as integrated). Among the programmes described by Goudas to illustrate his categorisation, the GOAL (Going for the Goal) programme [16] fell within the first category. This programme was designed to teach adolescents a sense of personal control and confidence about their future. It consisted of 10 sessions taught by selected and trained high school students to middle school or junior high school students. The SUPER (Sports United to Promote Education and Recreation) [17] programme was classified in the second category. This programme was taught in a manner similar to sports clinics, with participants involved in three sets of activities: learning the physical skills related to a specific sport; learning life skills related to sports in general; and playing the sport. The third category involves modifications of existing programmes so that these are embedded within the sport or PE practice, for instance, an abbreviated version of the SUPER programme [9]. This team-sports-based programme comprised three life skills: goal setting, problem-solving strategies, and positive thinking. The integrated nature of the programme is illustrated by the following situation. In several sessions, students were taught a three-step procedure for problem solving; then, they were presented with modified basketball and volleyball games requiring a novel solution and were asked to use the three-step procedure to find a solution.

From a didactic perspective oriented towards the study of the intertwined teaching and learning processes with a special focus on the knowledge taught [18[18][19],19], considering political and economic demands in learning and teaching PE through these contrasted types of programmes is likely to lead to tensions between the transmission of a core of subject knowledge and the requirement to address these societal issues, particularly in terms of motor skills learning. Depending on the ways in which these new social demands are met, i.e., isolated, juxtaposed, or integrated ways of teaching life skills as well as the didactic processing [20] of social practices taken as reference [21], wresearchers assume that PE will be rooted in different teaching traditions, with this concept initially highlighting what counts as content, goals, and values for science education [22,23][22][23]. Relying on an overview of the sport pedagogy literature to identify the traditions underlying the official discourses in PE, four broad educational directions for PE have been distinguished [24]. In the PE teaching tradition (PETT) “Teaching PE as sport-techniques”, PE content typically includes sports-specific movements or more generic and fundamental skills such as throwing, catching or kicking a ball. A hierarchical order from simple to complex elements is favoured and students have to master the easier skills before being confronted with the most advanced. Emphasis is generally placed on the surface features of motor techniques. The PETT “Teaching PE as health education” is based on the idea that PE should teach students to manage their physical activity and develop healthy lifestyles. PE is seen as a possible solution to the increasingly sedentary lifestyle, obesity, cardiovascular problems, etc., even if the link between PE and lifelong physical activity still needs to be firmly established, and the normativity of such an educational project faces many criticisms. According to the PETT “Teaching PE for values and citizenship”, the main objectives of PE are to teach students values such as self-responsibility, respect for differences, conflict resolution, and participation in the democratic class environment. Pedagogical models such as “Sport for Peace” [25] and “Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility” [26] in the USA, as well as “La République des sports (1964–1973)” [27] in France are emblematic of this tradition, which views PE as a place where political volition and the creation of today’s citizens are at the heart of the teaching. Finally, the PETT “Teaching PE as physical culture education”, which is still in construction and may be seen as an attempt to integrate the three previous perspectives, is not only about learning facts, methods, or how to think as a sportsperson, but it is also about being socialised into a specific view of embodied culture, i.e., “a broader corporeal discourse that is concerned with all aspects of meaning-making centred on the body” [28] (p. 98). “Teaching Games for Understanding” [29] in the UK, “Sport Education” [30] in the USA, and “Sport de l’enfant (1965–1975)” [31] in France are the pioneering pedagogical models of this tradition, all of which are rooted in such an integrative vision of physical culture.

2. Types of Programmes and Teaching Traditions

The life skills programmes wresearchers reviewed are shared between isolated (n = 3), juxtaposed (n = 3), and integrated (n = 7) ways of teaching life skills in PE. The isolated programmes refer to the PETTs “health education” and/or “values and citizenship”. The juxtaposed ones refer to the PETTs “sport-techniques”, “health education” and/or “values and citizenship”. Finally, the integrated ones refer to the PETTs “values and citizenship” or “physical culture education”. Table 1 illustrates this distribution between eight categories and subcategories of life skills programmes in PE.Table 1. Types of programmes and teaching traditions.

| Types of Programmes | Teaching Traditions | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Isolated | Health education | 1 |

| Health education/values and citizenship | 1 | |

| Values and citizenship | 1 | |

| Juxtaposed | Values and citizenship | 1 |

| Sport-techniques/health education | 1 | |

| Sport-techniques/health education/values and citizenship | 1 | |

| Integrated | Values and citizenship | 2 |

| Physical culture education | 5 | |

| Total | 13 |

Each person with a piece of paper and a pen draws a silhouette that represents him/her on a piece of paper. Then, using coloured pencils, they paint in which areas of the body they notice the different emotions and in which colour.A modular training model designed in particular for coaches and PE teachers, within the framework of the “No Violence in Sport” (NOVIS) project in Italy [35][34], illustrates an isolated way of teaching life skills, rooted in the PETT “values and citizenship”. This modular training is supplied in three macro-training units (TU). The first TU covers general topics such as relations between youth, sport clubs, and families, violence in sports, and values through sports. The second TU provides participants with didactic recommendations to create a mastery (task-involving) motivational climate in youth sports and PE and to promote inclusive education. The third TU is devoted to the implementation of multimedia didactic tools (e.g., sports charts, logbooks, videos). WResearchers categorised as juxtaposed and rooted in the PETT “values and citizenship” a brief description of sports-for-development type of programmes delivered as PE content by non-governmental organisations (NGO) in some lower quintile schools in South Africa [36][35]. In this context, the NGO coaches teach the sports-to-life approach and the students apply the values learnt in PE classes to real-life situations. In a paper focused on connections between social relationships and basic motor competences in early childhood in Switzerland [37][36], wresearchers found proposals aiming at preventing the exclusion of children with poor motor competence and, at the same time, creating situations in which those children experience the joy of movement and take the opportunity to improve their motor competence without feeling ashamed. These proposals, which weresearchers categorised as juxtaposed and rooted in both PETTs “sport-techniques” and “health education”, suggest that:In this context, extracurricular measures should also be examined and developed, such as the design of schoolyards that promote physical activity or the organisation of extracurricular sports-oriented activities that can, among other things, provide a meaningful rhythm to everyday school life.An intervention programme designed for students of elementary school (average age 14.6 years old) in Bosnia and Herzegovina [38][37] illustrates a juxtaposed way of teaching life skills in PE, rooted simultaneously in the three PETTs “sport-techniques”, “health education”, and “values and citizenship”. Besides the innovation in lesson organisation, methods of teaching formal skills/knowledge (e.g., basketball, soccer, etc.), and taking care of regular physical activity, the programme focuses on the improvement and application of the growth mindset, critical thinking, and self-cultivation through methods such as constructive feedback, conversations about topics such as success/defeat/win/loss, homework readings, and mindful meditative breathing techniques. A methodological intervention for developing respect, inclusion, and equality in PE [39][38] is a good example of an integrated way of teaching and learning these life skills, rooted in the PETT “values and citizenship”. The intervention is designed for 20 sessions in secondary school, twice per week, with a length of 50 min each. It is divided into six different sports modalities (athletics, volleyball, basketball, football, handball, intercross) as well as a final section of popular and traditional games. The following description of a final activity in athletics entitled “Blindfolded circuit (12 min)” is indicative of a teaching of PE in which life skills are dealt with by applying a didactic processing to social practices taken as reference that enhances their educational potential:There are two circuits formed with diverse materials, and the students will have to complete them blindfolded (one circuit per team). It consists of a zigzag in cones, hurdle crossing (passing underneath), jumping a step with two feet, searching for a cone to place in the hoop and the final sprint along the court. In pairs, the blindfolded one is guided by the partner, and they can touch each other.On the other hand, an integrative methodology for circus training based on the creativity and education of physical expression [40][39] illustrates an integrated way of teaching and learning creativity and risk-taking inherent in circus culture, rooted in the PETT “physical culture education”. For teachers and educators as well as the general population, this training programme consists of cycles of one trimester (12 weeks). The following description of a 20 min skill learning session aimed at mastering basic exercise for safety and autonomy illustrates how life skills are taught at the same time with skills representative of circus culture:This section begins with a sequence of preparatory or pre-acrobatic movements, followed by at least three variations of practice: repetitions of the most effective technical patterns; a directive/guided exercise for exploring different expressive dynamics; and a game of creating a dramatic composition for the movement actions.3. Contextual Variations

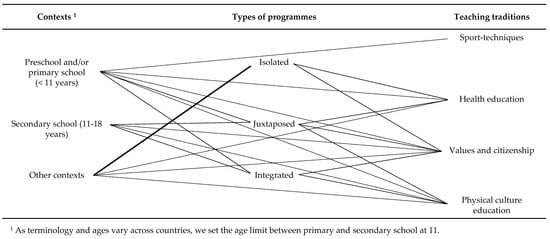

An overview of the connections between contexts (preschool and/or primary school, secondary school, and other contexts), types of programmes, and teaching traditions is presented in Figure 1.This overview shows little variations across contexts, except that: (a) all three programmes categorised as isolated come from studies conducted in a higher or teacher education context (as indicated by the bold connector) and (b) life skills programmes implemented in secondary schools are only rooted in the PETTs “values and citizenship” or “physical culture education”, whereas those implemented in primary schools are rooted in all four PETTs. Regarding the first difference, it might seem normal that future PE teachers are not directly confronted with sports practices during training units dedicated to life skills education. However, the concept of pedagogical isomorphism and other findings of this review ssuggest that this is not necessarily a suitable training strategy:Figure 1. Overview of the connections between contexts, types of programmes, and teaching traditions.Finally, it is important to acknowledge PDFs (professional development facilitators) play a pivotal role in delivering professional development programmes and supporting teachers learning. For example, in some cases, professional development programmes are delivered in a way where PE teachers do not actively engage with course materials, which can create a disconnect between theory and practice.The second difference could be put into perspective with the results of studies showing that the targeted life skills vary depending on the age of the students [7]. However, the numerous and varied (groups of) life skills addressed in the 13 programmes we reviewed (when specified) do not seem to vary between the contexts. They broadly correspond to the WHO’s five main life skills “areas” and to the majority of the concepts related to personal and social development within the context of PE [6]. Table 2 lists the life skills identified in the articles dealing, respectively, with our three categories of context.Table 2. Life skills taught in different contexts.Finally, it may be noted that all five programmes rooted in the PETT “physical culture education” rely on collective activities (team games, relay running, circus). The latter are processed in a didactic way, emphasising life skills inherent in their culture [41][40]: social inclusion, relational and emotional well-being, cooperation and empathy (prosocial) vs. quick-temperedness and disruptiveness (antisocial) in team games; collaboration, problem solving, conflict resolution, and working together in relay running; risk (of daring to act in a dialogue with spectators) and creativity (resulting in circus performances for an audience) in a circus.

Contexts Life Skills Preschool and/or primary school (<11 years) cooperation (prosocial), empathy (prosocial), quick-temperedness (antisocial), disruptiveness (antisocial), collaboration, problem solving, conflict resolution, working together. Secondary school (11–18 years) growth mindset, critical thinking, self-cultivation, various societal issues, prosocial behaviours, social inclusion, respect, equality, relational well-being, emotional well-being. Other contexts knowledge identification, understanding and management of emotions, emotional language, mindfulness of the senses and surroundings, intelligent optimism and positive emotions, critical analysis of negative emotions, resolution of intrapersonal and interpersonal conflicts, development of social skills, personal and social responsibility, conscious attitude towards own lives and health, mastering the basics of a healthy lifestyle, life skills of safe and healthy behaviour, creativity, risk, violence in sport (antisocial).

References

- Danish, S.; Taylor, T.; Hodge, K.; Heke, I. Enhancing youth development through sport. World Leis. J. 2004, 46, 38–49.

- Gould, D.; Carson, S. Life skills development through sport: Current status and future directions. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 1, 58–78.

- Cronin, L.; Marchant, D.; Johnson, L.; Huntley, E.; Kosteli, M.C.; Varga, J.; Ellison, P. Life skills development in physical education: A self-determination theory-based investigation across the school term. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2020, 49, 101711.

- WHO. Life Skills Education for Children and Adolescents in Schools. In Introduction and Guidelines to Facilitate the Development and Implementation of Life Skills Programmes; 1997. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/63552/WHO?sequence=1 (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- UNICE. Global Evaluation of Life Skills Education Programmes. Evaluation Summary. 2012. Available online: https://evaluationreports.unicef.org/GetDocument?fileID=242 (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Opstoel, K.; Chapelle, L.; Prins, F.J.; De Meester, A.; Haerens, L.; van Tartwijk, J.; De Martelaer, K. Personal and social development in physical education and sports: A review study. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2020, 26, 797–813.

- Kirchhoff, E.; Keller, R. Age-specific life skills education in school: A systematic review. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 660878.

- Goudas, M. Prologue: A review of life skills teaching in sport and physical education. Hell. J. Psychol. 2010, 7, 241–258.

- Goudas, M.; Giannoudis, G. A team-sports-based life skills program in a physical education context. Learn. Instr. 2008, 18, 538–546.

- Bean, C.; Kramers, S.; Forneris, T.; Camiré, M. The implicit/explicit continuum of life skills development and transfer. Quest 2018, 70, 456–470.

- Pierce, S.; Gould, D.; Camiré, M. Definition and model of life skills transfer. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 10, 186–211.

- Jacobs, J.M.; Wright, P.M. Thinking about the transfer of life skills: Reflections from youth in a community-based sport programme in an underserved urban setting. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2021, 19, 380–394.

- Ronkainen, N.J.; Aggerholm, K.; Ryba, T.V.; Allen-Collinson, J. Learning in sport: From life skills to existential learning. Sport Educ. Soc. 2021, 26, 214–227.

- Condello, G.; Mazzoli, E.; Masci, I.; De Fano, A.; Ben-Soussan, T.D.; Marchetti, R.; Pesce, C. Fostering holistic development with a designed multisport intervention in physical education: A class-randomized cross-over trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9871.

- Santos, F.; Neves, R.; Parker, M. Connecting TPSR and professional development: Implications for physical education teachers and facilitators. Strategies 2021, 34, 11–17.

- Danish, S.J.; Petitpas, A.J.; Hale, B.D. A developmental-educational intervention model of sport psychology. Sport Psychol. 1992, 6, 403–415.

- Danish, S.J. Sports United to Promote Education and Recreation (SUPER). Leader Manual; Virginia Commonwealth University: Richmond, VA, USA, 2002.

- Vors, O.; Girard, A.; Gal-Petitfaux, N.; Lenzen, B.; Mascret, N.; Mouchet, A.; Turcotte, S.; Potdevin, F. A review of the penetration of Francophone research on intervention in physical education and sport in Anglophone journals since 2010. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 25, 331–345.

- Amade-Escot, C. The contribution of two research programs on teaching content: “Pedagogical Content Knowledge” and “Didactics of Physical Education”. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2000, 20, 78–101.

- Amade-Escot, C. Les savoirs au coeur du didactique. In Le Didactique; Amade-Escot, C., Ed.; Editions Revue EP&S: Paris, France, 2007; pp. 11–30.

- Martinand, J.L. Pratiques de référence, transposition didactique et savoirs professionnels. Sci. L’éducation L’ère Nouv. 1989, 2, 23–29.

- Östman, L. Discourses, discursive meanings and socialization in chemistry education. J. Curric. Stud. 1996, 28, 37–55.

- Roberts, D.A. What counts as science education? In Development and Dilemmas in Science Education; Fensham, P.J., Ed.; Falmer Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 27–54.

- Forest, E.; Lenzen, B.; Öhman, M. Teaching traditions in physical education in France, Switzerland and Sweden: A special focus on official curricula for gymnastics and fitness training. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2018, 17, 71–90.

- Ennis, C.D.; Solmon, M.A.; Satina, B.; Loftus, S.J.; Mensch, J.; McCauley, M.T. Creating a sense of family in urban schools using the “Sport for Peace” curriculum. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 1999, 70, 273–285.

- Hellison, D. Teaching Responsibility through Physical Activity, 3rd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2011.

- Loudcher, J.F.; Vivier, C. Jacques de Rette et les Républiques des sports: Une expérimentation de la citoyenneté en EPS (1964–1973). Staps 2006, 73, 71–92.

- Kirk, D. Physical Education Futures; Routledge: London, UK; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2010.

- Bunker, D.; Thorpe, R. A model for the teaching of games in secondary school. Bull. Phys. Educ. 1982, 10, 9–16.

- Siedentop, D. Sport Education: A retrospective. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2001, 21, 409–418.

- Moustard, R.; Goirand, P.; Jounet, J.; Marsenach, J.; Portes, M. Les Stages Maurice Baquet: 1965–1975—Genèse du Sport de L’enfant; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2005.

- Savchuk, O.; Petukhova, T.; Petukhova, I. Training of future teachers for the formation of the competence of safe life of the younger generation. Rev. Rom. Pentru Educ. Multidimens. 2021, 13, 43–59.

- Fernández-Gavira, J.; Castro-Donado, S.; Medina-Rebello, D.; Bohórquez, M.R. Development of emotional competencies as a teaching innovation for higher education students of physical education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 300.

- Vitali, F.; Conte, S. Preventing violence in youth sport and physical education: The NOVIS proposal. Sport Sci. Health 2021, 18, 387–395.

- Burnett, C. A national study on the state and status of physical education in South African public schools. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2021, 26, 179–196.

- Herrmann, C.; Bretz, K.; Kühnis, J.; Seelig, H.; Keller, R.; Ferrari, I. Connection between social relationships and basic motor competencies in early childhood. Children 2021, 8, 53.

- Brankovic, E.; Badric, M. Preliminary validation of the Holistic Experience of Motivation Scale (HEMS): An empirico-philosophical approach. Croat. J. Educ. 2021, 23, 11–30.

- Muñoz-Llerena, A.; Núñez Pedrero, M.; Flores-Aguilar, G.; López-Meneses, E. Design of a methodological intervention for developing respect, inclusion and equality in physical education. Sustainability 2022, 14, 390.

- Tucunduva, B.B.P. An integrative methodology for circus training based on creativity and education on physical expression. Theatre Danc. Perform. Train. 2021, 12, 499–513.

- Travert, M.; Mascret, N. La Culture Sportive; Editions EP&S: Paris, France, 2011.

More