Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Emily Talen and Version 2 by Sirius Huang.

While scale is an essential factor in discussions about sustainable cities, there is no common understanding of what scale is or how it should be measured. Understanding scale and how it changes may shed light on answering a number of questions, such as how scale impacts livability, pedestrian quality, access, affordability, or crime. In order to delve into these and other scale-related topics, urbanists need an approach to scale measurement and analysis.

- urban scale

- mega-development

1. Introduction

The sustainable city, a concept that started in the 1970s as an “eco-city” movement that sought to build cities in balance with nature [1], is now generally defined as a city that exerts minimal damage on the environment while maintaining a diverse and resilient economy, an equitable distribution of resources, and a means of citizen participation. On all of these fronts—diversity, equity, engagement—small-scale urbanism is thought to have a better alignment with sustainability goals than large-scale urbanism [2]. Following the work of Jane Jacobs [3], urbanists have been promulgating the benefits of small-scale urbanism, denouncing the liabilities of large-scale form and arguing that neighborhoods that develop or redevelop on a small scale are the ones that are the most sustainable and resilient [4]. Large-scale urban developments—“mega-projects” in the form of town centers, university campuses, and other large format urban schemes—are viewed as antithetical to Jane Jacobs’ brand of incremental change, and the very opposite of a resilient and sustainable city [5][6][5,6].

While scale is an essential factor in discussions about sustainable cities, there is no common understanding of what scale is or how it should be measured. Is it about buildings, lots, and block sizes? Is it about single vs. corporate ownership of land? Is it about the geographical distances between points? Cities are aggregations of all of these elements —small lots with single family homes, 200-acre parcels with multi-use buildings with thousands of square feet, and infrastructure and public spaces ranging from intimate to vast. The variation of the scale of urbanism from small to large creates a multitude of effects and experiences.

2. The Scale of Urbanism

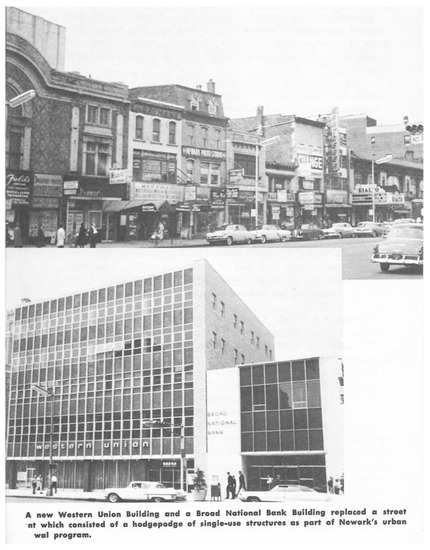

Cities have long developed at multiple scales simultaneously, for different purposes and with different effects. Large-scale development was an expression of political power, of absolutism, or of the centralizing force of an authoritarian regime. Monumental scale is a natural fit for authority and control, presupposing an “unentangled decision-making process” and expressing that the ruling authority has the necessary power to get things done [7] (p. 217). Alongside this larger scale, small-scale urban fabric was created and recreated by individual owners, developers of various sizes, and builders working in a more incremental manner. Urban change was accomplished lot by lot, block by block, through the work of many individual owners rather than despots, governments, or large developers [8]. A few important studies have attempted to document these scale changes. Warner and Whittemore [8] chart the evolution of an imagined U.S. city amalgamized from Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. They describe how, through the mid-18th century, most dwellings were small in part due to the high costs of construction. Even in the early streetcar era of massive rowhouse neighborhood expansion, most were built by craftsman at a rate of three to six per year, yet a homogeneity of style tended to develop outside of legal regulation. Hunter categorizes homes into three types: freestanding, attached, and apartments, and charts their evolution as forms in the American landscape [9]. Scheer expands this typology to include not just non-residential buildings, but also patterns of land subdivision, and emphasizes how historical patterns may constrain redevelopment possibilities [10]. Beyond historical analysis, the literature on scale has focused on debating the pros and cons of different scales. Debates about the effect of scale go back at least to the foundations of the field of planning, particularly in the U.S., when Daniel Burnham’s famously declared “make no little plans, for they fail to stir the hearts of men” [11]. Proponents of large development argue that this is the scale at which jobs are generated, infrastructure is financed, and city revenues are increased. The impulse to “go big” in city planning was further promulgated by modernist concepts of urbanism promoted through planners and architects associated with the Congres Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne, known as CIAM [12]. The large scale of modernist towers and freeway schemes prompted Jane Jacobs, among others, to castigate planners [3]. Mid-twentieth century urban renewal (Figure 1) was done at a large scale around the globe, and resulted in widespread displacement. In the U.S., large-scale urban renewal was often directed at African-Americans, prompting further debate about the issue of scale. Relatedly, Jacobs included the scale of finance in her critique, praising the benefits of “gradual money” over the deleterious effects of the “cataclysmic money” inherent in most large plans [3] (p. 291–317). These debates evolved into the 1970s economics of “Small is Beautiful” [13] and calls for informal incremental development as a solution to housing in the developing world [14].

Figure 1. Scale Change in the Urban Renewal Period. Mid-twentieth century urban renewal programs resulted in significant changes in scale. Above is an example from Newark, NJ, USA, c. 1950 and 1969. The bottom photograph replaced the upper one as part of Newark’s urban renewal program.