Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Fanny Huang and Version 1 by Valeria Calcaterra.

The ketogenic diet (KD) has attracted significant interest for the treatment of insulin resistance (IR) and for the control of carbohydrate metabolism, which has proven to be beneficial for several dysmetabolic conditions, including polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). The goal of the KD is to induce a fasting-like metabolism with production of chetonic bodies. Ketosis is a good regulator of calorie intake and mimics the starvation effect in the body, leading to body weight control and consequent metabolism. Additionally, during ketogenesis, insulin receptor sensitivity is also promoted.

- polycystic ovary syndrome

- diet

- ketogenic diet

- low-calorie ketogenic diet

1. Ketogenic Diet

The KD was drafted for the first time in 1920 as a dietary approach to the treatment of patients with drug-resistant epilepsies or with epilepsies secondary to rare metabolic diseases, such as GLUT-1 deficiency [51][1].

Over the years, globalization has led to general economic growth, greater access to food and an increase in physical inactivity; the main consequence of this process is the increased prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including obesity, metabolic and cardiovascular diseases and cancer. In this regard, the ketogenic diet has been used for the treatment of the aforementioned pathologies, showing positive impact [52][2].

The ketogenic dietary approach may be tailored considering different “protocols”, including the classic ketogenic diet (CKD), the low-calorie ketogenic diet (LCKD), the very-low-calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD), the isocaloric ketogenic diet (ICKD) and the modified ketogenic diet (MKD) [51][1].

KD composition is based on a reduced intake of carbohydrates (30–50 g/day), with different ratios between fat and protein intakes [51][1] aiming to induce ketosis, a condition in which the body is compelled to use ketone bodies (synthesized from fat) as an energy substrate instead of glucose [53][3]. When the KD is also low in energy, rapid weight loss and improvement of the metabolic profile have also been identified, mainly due to decreased insulin levels and increased glucagon levels, in addition to ketosis [54][4].

Furthermore, KD modifies the metabolic pathways of the subject, reducing lipogenesis and increasing lipolysis, influencing adipose tissue deposition and lipid plasma levels.

The KD has also been associated with antioxidant effects, generating a reduced amount of ROS (reactive oxygen species) and reshaping gut microbiota [6][5].

Regarding patients affected by obesity, the very-low-calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD) has been associated with a significant reduction in body weight and BMI, waist circumference and fat mass [55][6].

The rapid weight loss could be due to the impact of ketone bodies on appetite with decreased perception of hunger and, consequently, in a higher adherence to smaller food portions and less food consumption overall. In fact, KD acts on the central nervous system, regulating eating behavior [6][5].

Furthermore, the KD has been shown to lead to the reduction of hyperinsulinemia and the improvement of insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes [56][7]; the improvement of patients suffering from non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is instead determined by the reduction of insulin resistance due to the increased use of fatty acids in the ketogenesis process with consequent reduction of the synthesis of intrahepatic triglycerides (IHTG) [57][8].

Since several KDs have been developed over time, it is difficult to provide a standard definition of a “ketogenic protocol”. In this regard, Frigerio F. et al. [51][1] presented different types of KDs and classified them according to their composition, focusing primarily on energy and lipid intake. Others classify KDs according to the desired ketogenic ratio (KR), which is calculated in grams of fat to grams of protein plus carbohydrates, ranging usually from 1:1 to 4:1 [6,51][1][5].

In particular, regarding the VLCKD, it is divided into different phases involving the exclusion of many foods, so following this diet with normal food products could become monotonous and ineffective. In this regard, many companies are specializing in the production of foods modified from a technological point of view which, despite being low in carbohydrates, allow the patient’s choices to be broadened, thus making them more compliant with the proposed scheme. These products include soups, smoothies and bars, but also ready meals with controlled portions; these foods are therefore essential in controlling the daily caloric intake [58][9].

In the first phase, patients follow a VLCKD (around 600 and 800 kcal/day) or a LCKD (>800 kcal/day and <total energy expenditure) (50); the latter is preferred to meet needs and avoid deficiencies in adolescents with PCOS [56,59][7][10].

This phase usually lasts from 8 to 12 weeks, depending on the individual and the agreed weight loss [56][7].

The next phase consists of a gradual reintroduction diet in which previously excluded foods are reintroduced into the patient’s diet, starting with foods with the lowest glycemic index (fruit, dairy products), followed by foods with a moderate glycemic index (legumes) and high-glycemic-index foods (bread, pasta and cereals) [2][11].

Fundamental in this phase is the figure of the professional (doctor, dietician...), who accompanies the patient on a path of nutritional education in order to implement a balanced diet. This has a twofold objective: the continuation of slimming and the maintenance of the weight achieved, and the promotion of a healthy lifestyle to improve the individual’s well-being and prevent the onset of NCDs [55][6].

As already underlined, KD provides for the exclusion of foods, including cereals and derivatives, fruit, various types of vegetables and some dairy products. It follows a reduced intake of some vitamins and minerals, such as calcium, vitamin D, potassium, sodium and magnesium, for which patients could develop deficiency. Because of this, it is essential to be integrated with a specific vitamin/mineral supplementation [52][2].

In order to avoid these consequences, the followed parameters also need to be monitored before, during and at the end of the diet:

- –

-

Physical examination (anthropometric measurements, blood pressure, heart rate, etc.);

- –

Although transient, there are several side effects that can appear in subjects who follow a KD. Indeed, the reduction in energy and carbohydrate intake and the consequent formation of ketone bodies can lead to the onset of fatigue, headache, hypoglycemia and halitosis. The lack of fiber intake can instead lead to constipation and intestinal discomfort. However, these effects usually resolve within a few days to weeks of KD initiation [55,56][6][7].

2. Ketogenic Diet and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Among the interventions for the treatment of PCOS that have been shown to have a positive impact on cardiometabolic health, decrease in androgen levels and menstrual irregularity, the modification of lifestyle is of particular importance, including physical activity, diet, regular sleep and weight loss when needed [4][12].

In patients with excessive weight, achievable goals, such as 5% to 10% weight loss within six months, led to significant clinical improvements [2][11].

For example, Marzouk et al. demonstrated that dietary weight loss in adolescent women with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 kg/m2 led to significant improvement in menstrual regularity, hirsutism score and anthropometric parameters [60][13].

An improvement in the metabolic profile and a decrease in circulating testosterone was observed also by Gower et al. after a modest reduction in dietary carbohydrate intake [61,62][14][15].

In a 2013 study, Mehrabani et al. showed that both a balanced hypocaloric diet and a high-protein, low-glycemic-load, hypocaloric diet led to significant weight loss and reduction in androgen levels, and the second type of diet led also to improvement in insulin sensitivity [62,63][15][16].

In a 2020 meta-analysis evaluating whether low-calorie diets improved insulin sensitivity in women with PCOS, a greater reduction in insulin resistance (IR) was reported when a low-carbohydrate diet was prescribed rather than a high-carbohydrate diet [64][17].

This could be explained by the fact that excessive carbohydrate (CHO) intake leads to constant low-grade inflammation associated with IR and hyperandrogenism, resulting in increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), oxidative stress and inflammation [65][18].

This is also supported by the randomized controlled clinical trial conducted by Mei et al. in 2022 on a sample of 72 overweight women with PCOS (aged between 16 and 45), who followed a MD combined with a low-carbohydrate (LC) dietary model for 12 weeks, observing an improvement in anthropometric and endocrine parameters [65,66][18][19].

Therefore, among various dietetic patterns, ones with low CHO intake such as different KD protocols have been considered by some authors in women affected by overweight or obesity and diagnosed with PCOS.

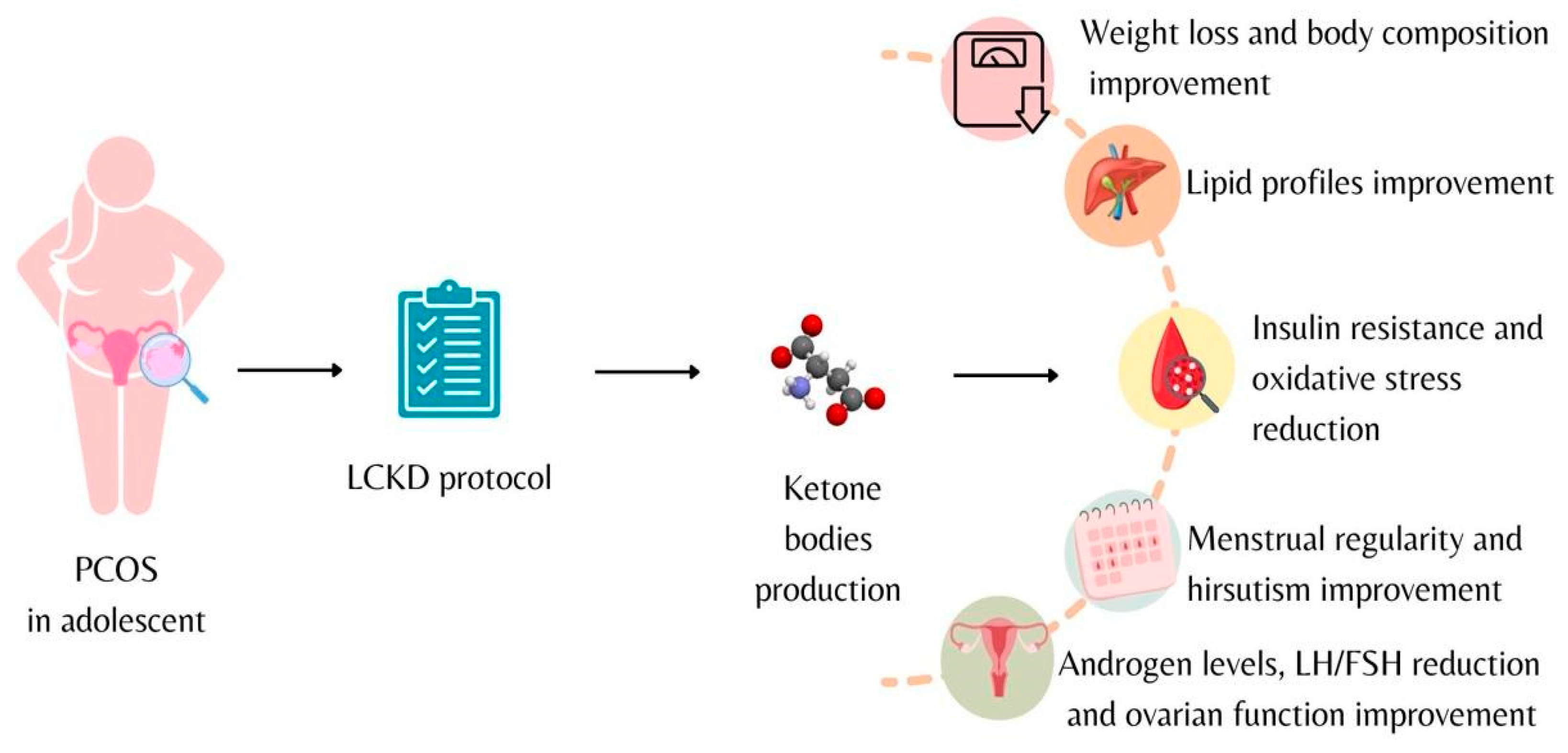

In a 2013 review, Paoli et al. suggested how KD may have therapeutic action in some metabolic and endocrine diseases, including PCOS, by improving hyperinsulinemia and associated consequences, such as hyperandrogenism [6,66,67][5][19][20]. The potential effects of KD are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Low-calorie ketogenic diet effects on adolescents diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome.

One of the first studies regarding this topic is a pilot study conducted in 2005 on a sample of 11 women of childbearing age (18–45 years old), diagnosed with PCOS with mean BMI 38.5 kg/m2. This study evaluated the effects of a LCKD followed for 24 weeks, showing that in the five women who completed the study, there was a significant reduction in body weight, percent free testosterone, LH/FSH ratio, fasting serum insulin and symptoms. Furthermore, improvement of ovulatory function led to pregnancy of two women after 4 weeks [67,68][20][21].

In the last few years, studies conducted in 2020 by Paoli et al. [68][21], in 2021 by Cincione et al. [69][22] and in 2022 by Magagnini et al. [70][23] have shown that the use of different protocols (in terms of duration and composition) of KD in a population aged, respectively, 16–45, >18 and 18–45 of overweight and obese women diagnosed with PCOS led to statistically significant results on endocrine and metabolic parameters.

In particular, in all the considered studies, after treatment with the KD for 12 weeks and 45 days, improvements were demonstrated in anthropometric parameters and body composition [69,70,71][22][23][24].

A significant reduction of the HOMA index was observed as well as in lipid profile (total cholesterol, low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride levels), along with an increase in high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-col).

Interesting results have also been shown in hormonal and ovulatory function, with significant increase in sex-hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and significant reduction of circulating androgens such as free testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEAs).

In all three studies, an increase in estradiol and progesterone, a reduction in the luteal hormone/follicle-stimulating hormone (LH/FSH) ratio and a significant reduction in the anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) were also found [69,70,71][22][23][24].

These outcomes were confirmed by a 2023 randomized controlled trial, lasting 16 weeks, aimed at evaluating the efficacy of a very-low-calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD) compared to a balanced low-calorie diet (LCD) in women of childbearing potential (18–45 years) with PCOS suffering from obesity [72][25].

In conclusion, studies regarding the use of VLCKD in women with PCOS and excessive body weight are still numerically limited, but they are rapidly increasing.

In Table 1, the main studies on effects of KD on PCOS included are resumed.

Table 1. Main studies on effects of ketogenic diet on polycystic ovary syndrome included.

| First Author, Year of Publication | Title | Study Type | Population | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paoli et al., 2020 [61][14] | Effects of a ketogenic diet in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. | Single-arm study (interventional) | 24 overweight women with PCOS Age: 18–45 yo |

Participants followed a ketogenic diet (KD) for 12 weeks | KD as a possible therapeutic aid in PCOS |

| Cincione et al., 2021 [62][15] | Effects of Mixed of a Ketogenic Diet in Overweight and Obese Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. | Interventional study | 17 overweight and obese women with PCOS Age: 18–45 yo |

Participants were treated for 45 days with a modified KD protocol, defined as “mixed ketogenic” | KD improves the anthropometric and many biochemical parameters (LH, FSH, SHBG, insulin sensitivity and HOMA index) and reduces androgenic production |

| Magagnini et al., 2022 [63][16] | Does the Ketogenic Diet Improve the Quality of Ovarian Function in Obese Women? | Retrospective study | 25 women with PCOS and first-degree obesity Age: ≥18 yo |

Participants followed a VLCKD protocol for 12 weeks | Metabolic and ovulatory improvement is achieved in a relatively short time |

| Pandurevic et al., 2023 [64][17] | Efficacy of very-low-calorie ketogenic diet with the Pronokal® method in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a 16-week randomized controlled trial | Randomized controlled trial | 32 childbearing age women with PCOS, BMI 28–40 kg/m2 Age: 18–45 yo |

Experimental group (n = 15): VLCKD for 8 weeks then LCD for 8 weeks, according to the Pronokal® method; Control group (n = 15): Mediterranean LCD for 16 weeks | In obese PCOS patients, 16 weeks of VLCKD protocol with the Pronokal® method was more effective than Mediterranean LCD in reducing total and visceral fat, and in ameliorating hyperandrogenism and ovulatory dysfunction |

The VLCKD in this target population has showed a positive impact on multiple short-term clinical aspects (weight and fat mass loss, IR reduction, improvement in glucose, lipid homeostasis, reduction in androgen levels and LH/FSH ratio and increase of SHBG).

This was also reported in a 2019 systematic review of the “Italian Society of Endocrinology” [52][2], which, however, concludes that the use of the VLCKD in patients with PCOS affected by obesity presents only preliminary evidence, and therefore the degree of recommendation appears to be limited.

Despite this, there are still some concerns about the potential risks of the VLCKD, and the studies conducted so far regarding its use in the treatment of obesity, also in children and adolescent populations, show some limitations, including: protocols studied in the short term and high dropout due to possible side effects; poor compliance due to the strict dietary pattern and its application in daily life (lack of acceptance of certain foods, poor palatability, ...); economic impact and consequences on the social sphere; risk of onset of eating disorders (ED) from the VLCKD (as a very selective dietary pattern).

In this regard, a less drastic dietary model in terms of energy intake, such as a LCKD, may be necessary in order to avoid the possible undesirable effects mentioned above and any nutritional deficiencies, which could affect the correct development of this target population.

Nonetheless, the potential effects that the state of ketosis determines on the decrease in appetite and the increase in the sense of satiety should not be underestimated: this condition could decrease the number of dropouts and determine a positive response to the clinical–nutritional outcomes [52,55][2][6].

References

- Frigerio, F.; Poggiogalle, E.; Donini, L.M. Definizione di dieta chetogena: Creatività o confusione? L’Endocrinologo 2022, 23, 587–591.

- Caprio, M.; Infante, M.; Moriconi, E.; Armani, A.; Fabbri, A.; Mantovani, G.; Mariani, S.; Lubrano, C.; Poggiogalle, E.; Migliaccio, S.; et al. Very-Low-Calorie Ketogenic Diet (VLCKD) in the Management of Metabolic Diseases: Systematic Review and Consensus Statement from the Italian Society of Endocrinology (SIE). J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2019, 42, 1365–1386.

- McGaugh, E.; Barthel, B. A Review of Ketogenic Diet and Lifestyle. Mo. Med. 2022, 119, 84–88.

- Muscogiuri, G.; Barrea, L.; Laudisio, D.; Pugliese, G.; Salzano, C.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A. The Management of Very Low-Calorie Ketogenic Diet in Obesity Outpatient Clinic: A Practical Guide. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 356.

- Calcaterra, V.; Regalbuto, C.; Porri, D.; Pelizzo, G.; Mazzon, E.; Vinci, F.; Zuccotti, G.; Fabiano, V.; Cena, H. Inflammation in Obesity-Related Complications in Children: The Protective Effect of Diet and Its Potential Role as a Therapeutic Agent. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1324.

- Muscogiuri, G.; El Ghoch, M.; Colao, A.; Hassapidou, M.; Yumuk, V.; Busetto, L.; Obesity Management Task Force (OMTF) of the European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). European Guidelines for Obesity Management in Adults with a Very Low-Calorie Ketogenic Diet: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes. Facts 2021, 14, 222–245.

- Batch, J.T.; Lamsal, S.P.; Adkins, M.; Sultan, S.; Ramirez, M.N. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Ketogenic Diet: A Review Article. Cureus 2020, 12, e9639.

- Luukkonen, P.K.; Dufour, S.; Lyu, K.; Zhang, X.-M.; Hakkarainen, A.; Lehtimäki, T.E.; Cline, G.W.; Petersen, K.F.; Shulman, G.I.; Yki-Järvinen, H. Effect of a Ketogenic Diet on Hepatic Steatosis and Hepatic Mitochondrial Metabolism in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 7347–7354.

- Kim, J.Y. Optimal Diet Strategies for Weight Loss and Weight Loss Maintenance. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2021, 30, 20–31.

- Conway, G.; Dewailly, D.; Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Escobar-Morreale, H.F.; Franks, S.; Gambineri, A.; Kelestimur, F.; Macut, D.; Micic, D.; Pasquali, R.; et al. The Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Position Statement from the European Society of Endocrinology. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 171, P1–P29.

- Teede, H.J.; Misso, M.L.; Costello, M.F.; Dokras, A.; Laven, J.; Moran, L.; Piltonen, T.; Norman, R.J.; International PCOS Network. Recommendations from the International Evidence-Based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 364–379.

- Calcaterra, V.; Verduci, E.; Cena, H.; Magenes, V.C.; Todisco, C.F.; Tenuta, E.; Gregorio, C.; De Giuseppe, R.; Bosetti, A.; Di Profio, E.; et al. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Insulin-Resistant Adolescents with Obesity: The Role of Nutrition Therapy and Food Supplements as a Strategy to Protect Fertility. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1848.

- Marzouk, T.M.; Sayed Ahmed, W.A. Effect of Dietary Weight Loss on Menstrual Regularity in Obese Young Adult Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2015, 28, 457–461.

- Gower, B.A.; Chandler-Laney, P.C.; Ovalle, F.; Goree, L.L.; Azziz, R.; Desmond, R.A.; Granger, W.M.; Goss, A.M.; Bates, G.W. Favourable Metabolic Effects of a Eucaloric Lower-Carbohydrate Diet in Women with PCOS. Clin. Endocrinol. 2013, 79, 550–557.

- Mehrabani, H.H.; Salehpour, S.; Amiri, Z.; Farahani, S.J.; Meyer, B.J.; Tahbaz, F. Beneficial Effects of a High-Protein, Low-Glycemic-Load Hypocaloric Diet in Overweight and Obese Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Intervention Study. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2012, 31, 117–125.

- Porchia, L.M.; Hernandez-Garcia, S.C.; Gonzalez-Mejia, M.E.; López-Bayghen, E. Diets with Lower Carbohydrate Concentrations Improve Insulin Sensitivity in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 248, 110–117.

- Barrea, L.; Marzullo, P.; Muscogiuri, G.; Di Somma, C.; Scacchi, M.; Orio, F.; Aimaretti, G.; Colao, A.; Savastano, S. Source and Amount of Carbohydrate in the Diet and Inflammation in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2018, 31, 291–301.

- Mei, S.; Ding, J.; Wang, K.; Ni, Z.; Yu, J. Mediterranean Diet Combined With a Low-Carbohydrate Dietary Pattern in the Treatment of Overweight Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Patients. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 876620.

- Paoli, A.; Rubini, A.; Volek, J.S.; Grimaldi, K.A. Beyond Weight Loss: A Review of the Therapeutic Uses of Very-Low-Carbohydrate (Ketogenic) Diets. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 789–796.

- Mavropoulos, J.C.; Yancy, W.S.; Hepburn, J.; Westman, E.C. The Effects of a Low-Carbohydrate, Ketogenic Diet on the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Pilot Study. Nutr. Metab. 2005, 2, 35.

- Paoli, A.; Mancin, L.; Giacona, M.C.; Bianco, A.; Caprio, M. Effects of a Ketogenic Diet in Overweight Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 104.

- Cincione, R.I.; Losavio, F.; Ciolli, F.; Valenzano, A.; Cibelli, G.; Messina, G.; Polito, R. Effects of Mixed of a Ketogenic Diet in Overweight and Obese Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 12490.

- Magagnini, M.C.; Condorelli, R.A.; Cimino, L.; Cannarella, R.; Aversa, A.; Calogero, A.E.; La Vignera, S. Does the Ketogenic Diet Improve the Quality of Ovarian Function in Obese Women? Nutrients 2022, 14, 4147.

- Pandurevic, S.; Mancini, I.; Mitselman, D.; Magagnoli, M.; Teglia, R.; Fazzeri, R.; Dionese, P.; Cecchetti, C.; Caprio, M.; Moretti, C.; et al. Efficacy of Very Low-Calorie Ketogenic Diet with the Pronokal® Method in Obese Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A 16-Week Randomized Controlled Trial. Endocr. Connect. 2023, 12, e220536.

- Barrea, L.; Verde, L.; Camajani, E.; Cernea, S.; Frias-Toral, E.; Lamabadusuriya, D.; Ceriani, F.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A.; Muscogiuri, G. Ketogenic Diet as Medical Prescription in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 56–64.

More