There are three application areas that have been accelerating the demand for cargo drones: (1) deliveries to areas with limited accessibility, such as oil rigs, ships, remote communities, islands, mountainous regions, disaster areas, and communities with poor roads; (2) rapid delivery of emergency medical items, such as antidotes, resuscitation equipment, injections, bandages, blood, and human transplant organs; and (3) same-day or same-hour delivery of packages and food in congested urban environments. All three applications can involve both middle-mile (between hubs) and last-mile (hub to home) deliveries. The focus of this research is on opportunities to increase the speed and reduce the risk of middle-mile delivery of pharmaceuticals by using emerging cargo drone technologies.

1. Introduction

The demand for pharmaceutical products will increase with population growth and increases in life expectancy because of the increased likelihood of more chronic diseases, more cases of age-related illnesses, and greater health awareness. In parallel, the increased frequency of weather events and traffic congestion is likely to result in future supply chain disruptions. This points to the need for faster, safer, more secure, and more reliable methods of transporting medical products. Conventional air cargo is faster, safer, and more secure than ground transport modes, but air cargo is much more expensive and difficult to access at busy airports and seaports

[1]. Cargo drone manufacturers believe their emerging products will reduce cost and increase accessibility while retaining all the speed, safety, and security advantages of air cargo

[2]. Consequently, governments and future logistic service providers are collaborating in an initiative called Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) to create a standard for the safe integration of drones into the commercial air space

[3].

Analysts expect that the market for cargo drones will be $58 billion by 2035

[4]. Several factors have motivated the development of cargo drone technology. Cargo drones can increase accessibility to locations that are difficult to reach by roads and offer higher throughput from greater vehicle utilization and swarming capabilities

[5]. The ability to autonomously control a drone swarm, enabled by machine vision, artificial intelligence, and advanced cellular communications, increases capacity and removes the expense of human operators

[6]. Mode shift from trucks to electrified cargo drones can reduce greenhouse gas emissions

[7]. In particular, shifting cargo from trucks to drones can improve the speed and reliability of deliveries by avoiding road traffic disruptions, such as incidents, congestion, construction, and accumulations from inclement weather. Additionally, shifting cargo away from heavy truck traffic will help to extend the life of the surface transportation infrastructure.

Supply chain disruptions as experienced during the 2020 global pandemic spotlighted the risk of delivering medical products that are critical to maintaining human health. Consequently, companies turned to the use of drones for “last-mile” deliveries. However, only a few locations in the world used drones to deliver medical products, such as blood, vaccine, and human organs

[8]. However, whilst such applications discuss last-mile deliveries to end-users, there has been a lack of research to assess the potential benefits of using drones for “middle-mile” deliveries to complete the logistical chain

[9]. Therefore, the goal of this research is to quantify the opportunity for drones to transport pharmaceutical products between hubs (middle mile deliveries) to reduce risks from potential ground traffic disruptions. The objective is to develop a data-driven analytical workflow that can identify the fewest metropolitan areas where initial service deployments can yield the greatest benefits. The rationale of focusing deployments to a few regions is to minimize initial deployment costs while demonstrating large early benefits to encourage policies and standards for sustained adoption.

2. Advanced Air Mobility

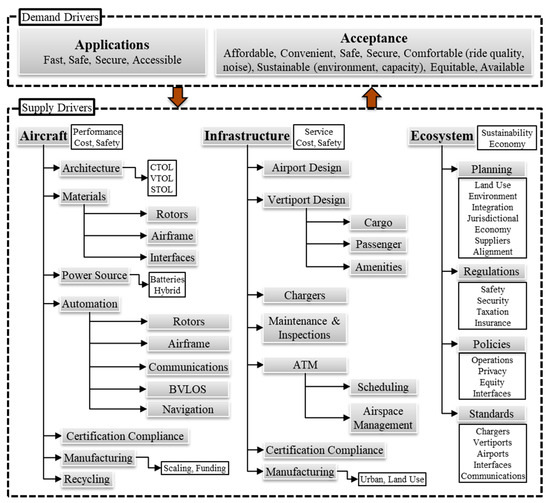

Figure 1 is the author’s empirical classification of supply and demand factors that are crucial for the success of AAM development. The two main demand drivers are applications and community acceptance. Drones are best suited for applications that demand transport that is fast, safe, secure, and accessible

[10]. User acceptance increases as the transport mode becomes more affordable, convenient, safe, secure, comfortable (low noise and good ride quality), non-polluting, equitable, and available

[11].

Figure 1.

Empirical classification of key factors in the adoption of AAM.

Supply drivers are within the three pillars of aircraft, infrastructure, and ecosystem. There is a complex interaction and feedback among the two demand drivers and three supply pillars. The aircraft design must meet the demand for speed, range, capacity, and safety at a cost that allows manufacturing to scale with demand

[12]. Factors that affect aircraft performance and cost are the architecture type, construction material, energy density and capacity of the power source, and technologies that enable safe and automated navigation

[13]. The common architecture types are conventional takeoff and landing (CTOL), vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL), and short takeoff and landing (STOL). Each architecture type trades off some performance or cost to be certifiable, operate in beyond visual line-of-sight (BVLOS) conditions in all types of weather

[14], scale in manufacturing, and be recyclable

[15]. The effectiveness of the terminal design, battery charging infrastructure, advanced traffic management (ATM), and integration in the environment affects safety, security, cost, convenience, accessibility, and the quality of services provided

[1]. The infrastructure should also facilitate coordination with other modes of ground transportation to enable hybrid systems, such a truck-drone operations

[16].

As a disruptive technology

[17], enabling adoption will require the ecosystem to form partnerships with planners, suppliers, regulators, policymakers, investors, funders, and developers of relevant standards to promote interoperability, compatibility, and scalability of the planned operations and services.

3. Medical Drone Deliveries

The healthcare community has been evaluating the use of drones to deliver medical items, such as surgical items, laboratory samples, pharmaceuticals, vaccines, emergency equipment, and blood

[18]. Early deployments narrowly focused on transporting medical products to mass casualty scenes in times of critical demand

[19]. Agencies used drones to deliver rescue medicines, such as epinephrine, antiepileptics, and insulin, to natural disaster areas in Haiti (2010 earthquake), Philippines (2013 earthquake), Taiwan (2016 typhoon), and Nepal (where flooding is frequent)

[20].

Several studies discussed the life-saving benefits of using drones to deliver emergency medical items. Laksham (2019) explored the potential for drones to deliver anti-venom, analgesics, antiretroviral, and malaria drugs to areas where road access is difficult

[21]. Beck et al. (2020) demonstrated the feasibility of using drones to rapidly deliver adrenaline auto-injectors to treat anaphylaxis

[22]. Scalea et al. (2021) demonstrated that they could integrate drones into the current system of organ delivery to save human lives

[23].

Many studies discussed how automated external defibrillator (AED) equipped drones can increase the survival rate of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) by rapidly delivering the equipment to bystanders

[24]. However, Mermiri et al. (2020) highlighted that even though mortality increases by 7% to 10% for every minute of delay in resuscitation, AED use in OHCA is not yet common

[25]. Based on successful experiments in Germany, Baumgarten et al. (2022) concluded that it was safe to transport AEDs by drones

[26]. Experiments by Cheskes et al. (2020) found that AED-equipped drones were 1.8 to 8 min faster than ambulances

[27]. Experiments by Pulver and Wei (2018) in Salt Lake County found that AED-equipped drones can respond within one minute

[28]. Experiments by Claesson et al. (2016) in Stockholm concluded that AED-equipped drones provided mean time savings of 19 min in rural areas

[29]. AED-equipped drones can help save lives, but community acceptance is necessary for adoption

[30]. In related work, Truog et al. (2020) found that the public is mostly supportive of drone use when organizations apply them for social good

[31].

Many studies have discussed how drones can enhance healthcare in areas with limited accessibility

[32]. Drones can access regions blocked by waterways or lakes, or places with poor roads, inhospitable terrain, and dense forests

[10]. O’Keeffe et al. (2020) have described how they used drones to successfully deliver insulin to the Aran Islands off the coast of Ireland

[33]. In a related study, Hii et al. (2019) found that the quality of insulin transported by drones did not degrade

[34]. The United Nations collaborated with the government of Malawi to evaluate how drones can facilitate the testing of babies for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

[35]. Mozambique evaluated the use of drones to transport tuberculosis sputum samples

[31]. Saeed et al. (2021) discussed how healthcare centers can use drones to increase accessibility to COVID-19 testing amid lockdowns by transporting test kits and samples

[36].

Drones can add value to the management of a blood supply chain that seeks to maximize supply and minimize waste

[37]. Zipline has been growing its drone service in Rwanda to deliver blood and blood products to hospitals and clinics in remote communities with difficult terrain

[8]. A positive side effect of regular and direct blood delivery by air was the reduction of spoilage from overstocking at the supply center. Many studies have also showed how blood delivery by drones can help in obstetric emergencies and to treat post-partum hemorrhages

[38]. For example, Tanzania, a country with one of the highest maternal mortality rates, successfully implemented a drone program to transport blood

[39].

Several studies have addressed issues in the logistic design of a medical drone delivery system. Dhote and Limbourg (2020) developed a drone network model, including charging station distribution, to optimize the logistics of transporting biological material in Brussels

[40]. Ghelichi et al. (2021) developed a model to optimize the logistics for a fleet of drones to deliver medical items, such as medicines, test kits, and vaccines, in rural and suburban areas with poor accessibility

[41]. Jackson and Srinivas (2021) evaluated drone-only, drone-truck hybrid, and truck-only modes to confirm the speed advantage of drone-only modes in pharmaceutical delivery services

[42]. Amicone et al. (2021) proposed a drone-optimized smart capsule with integrated real-time quality monitoring and control for perishable and high-value medical products

[43]. Li et al. (2021) proposed an Internet-connected medicine cabinet that drones can restock to reduce the mismanagement of medication dispensing at centers for the elderly

[44]. In related work, Lin et al. (2018) examined the legal landscape concerning the delivery of medications directly to private homes

[45].

As observed in the literature re

svie

arch w above, there is much written about the benefits of using drones to deliver medical items directly to end users. However, there are gaps in research about leveraging drones for “middle-mile” logistics. Firstly, a study noted that poorly executed middle-mile logistics can disrupt the effectiveness of “last-mile” deliveries

[46]. Secondly, only a few studies evaluated methods to inform data-driven decision making in drone logistics

[47]. This research contributes towards filling both gaps.