Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Bruna Scaggiante, and Version 2 by Jessie Wu.

Urothelial carcinoma (UC), the sixth most common cancer in Western countries, includes upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) and bladder carcinoma (BC) as the most common cancers among UCs (90–95%). BC is the most common cancer and can be a highly heterogeneous disease, including both non-muscle-invasive (NMIBC) and muscle-invasive (MIBC) forms with different oncologic outcomes. Approximately 80% of new BC diagnoses are classified as NMIBC after the initial transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBt).

- non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer

- bladder sparing treatment

- chemo-hyperthermia

- immunotherapy

- gene

1. Introduction

Urothelial carcinoma (UC), which includes bladder carcinoma (BC) and upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC), is the sixth most common cancer in Western countries [1]. BC, as the most common cancer, is a highly heterogeneous disease that includes both non-muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma (NMIBC) and muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma (MIBC) with different oncologic outcomes [2][3][4][2,3,4]. Approximately 80% of newly diagnosed bladder carcinomas are classified as NMIBC after the initial transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBt), representing a broad spectrum of disease [5]. While low-risk NMIBC patients are mainly treated with TURBt alone, intermediate- and high-risk patients often receive adjuvant treatments to reduce disease recurrence and progression [5][6][7][5,6,7]. In this context, intravesical administration of Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) is the current standard treatment [8]. Despite adequate BCG treatment, recurrence occurs in approximately 40% of patients and MIBC in 15% [9]. In particular, highly recurrent BCs represent the highest risk of disease [8]. The European Association of Urology guidelines (EAU) currently define “BCG-unresponsive” as all BCG-refractory tumors and those that develop T1/Ta HG recurrence within six months of completion of adequate BCG exposure or develop carcinoma in situ (CIS) within twelve months of completion of adequate BCG exposure. “Adequate BCG exposure” is defined as the completion of at least five of six doses of a first induction course plus at least two of six doses of a second induction course or two of three doses of a maintenance regimen. Patients with NMIBC who do not respond to BCG are extremely unlikely to benefit from further BCG administration and represent a patient cohort for whom new treatment options are urgently needed [10]. High-risk NMIBCs who do not respond to BCG, therefore, present a therapeutic challenge.

In this specific scenario, non-surgical options are limited, and according to the EAU guidelines [5][11][5,11], the recommended treatment for BCG-unresponsive disease remains radical cystectomy (RC) and urinary diversion (UD). RC and UD remain complex major urological procedures with a recognized high perioperative morbidity due to patient, disease, and surgical factors [12][13][12,13]. Numerous improvements have been made in surgical technique and perioperative management [14]. However, the morbidity profile and survival after RC have remained largely unchanged [15][16][17][15,16,17]. As this is a predominantly elderly disease, a non-negligible number of patients are considered unsuitable for such surgery [16].

Despite the unsatisfactory efficacy profile, with a complete response rate (CR) of about 18%, by 2020 the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved conservative treatment for CIS patients who did not respond to BCG was intravesical valrubicin [18]. Nowadays, new therapeutic options, potentially ready for the first time, could lead to a turning point in the treatment of patients who do not respond to BCG. In such a scenario, two unmet clinical needs could emerge. First, reliable biomarkers could identify early those patients who do not respond to BCG immunotherapy. Second, the current arsenal of new intravesical and systemic treatment candidate agents could be expanded for bladder-sparing strategies. If the identification of new molecular biomarkers is of interest for all disease stages of BC [19][20][21][19,20,21], the choice of new treatment candidates for NMIBC is wide, leading the FDA to accept single-arm clinical trials as adequate clinical evidence for evaluating therapeutics [22][23][24][22,23,24]. The choice of new treatment candidates for NMIBC is wide, leading the FDA to accept single-arm clinical trials as adequate clinical evidence for evaluating therapeutics.

2. Intravesical Chemotherapy

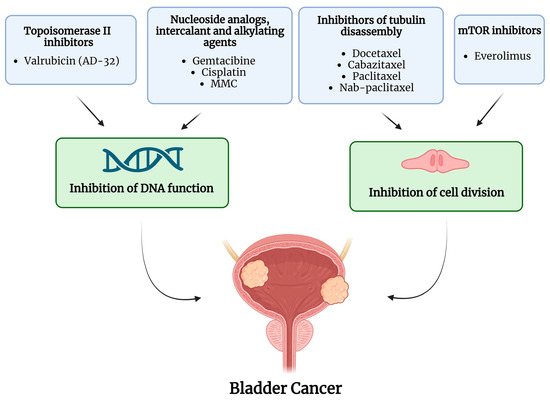

Over the years, intravesical administration of various chemotherapeutic agents has been investigated in BCG-unresponsive NMIBC. Figure 1 summarizes the drugs and mechanisms of action of intravesical chemotherapies; Table 1 summarizes the studies on intravesical treatments and the main findings over the last twenty years.

Figure 1.

Active molecules and mechanism of action of intravesical chemotherapy. The image was created with

.

Table 1.

Studies on intravesical administration of chemotherapy in NMIBC patients after BCG.

| Author, Year | Patients Number | Study Design | Treatment | Regimen | Effects of Treatment | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chevuru et al., 2023 [25] | 97 | Retrospective | Gemcitabine Docetaxel |

Induction +/− maintenance | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis Docetaxel: inhibition of cell division |

12, 24, and 60 months RFS 57%, 44%, and 24% (12, 24, and 60 months HG-RFS 60%, 50%, and 30%, respectively); BCG unresponsive: 12, 24, and 60 months RFS 67%, 50%, and 28%; CIS-only: 1-, 2-, and 5-year RFS 48%, 38%, and 22%, papillary only: 1-, 2-, and 5-year RFS 64%, 49%, and 25% (p = 0.3); 12, 24, and 60 months RC-free survival 89%, 86%, and 75% |

| Hurle et al., 2020 [26] |

36 | Open-label, single-arm | Gemcitabine | Induction +/− maintenance | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis | 12 and 24 months DFS 44.44% (95% CI 28.02–59.64%) and 31.66% (95% CI 16.97–47.43%); 12 and 24 months PFS 80.13% (95% CI: 62.78–90.00%) and 69.55% (95% CI: 50.33% 82.52%), 24 months CSS 80.68% (95% CI 61.49–90.96%), 24 months OS 77.9% (95% CI 58.78–88.92%) |

| Steinberg et al., 2020 [27] | 276 | Retrospective | Gemcitabine Docetaxel |

Induction +/− maintenance | Gemcitabine: inhibition DNA synthesis Docetaxel: inhibition of cell division |

1 and 2 years RFS 60% and 46% (43% if CIS present); HG 1 and 2 years RFS 65% and 52% (50% if CIS present) |

| DeCastro et al., 2020 [28] | 18 | Phase I trial | Cabazitaxel Gemcitabin Cisplatin |

Induction +/− maintenance (cabazitaxel + gemcitabine) | Cabazitaxel: inhibition of cell division Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis Cisplatin: inhibition of DNA replication and transcription |

CR rate: 89%; PR: 94% (negative biopsy but positive cytology). One and two years RFS 0.83 (range 0.57 to 0.94) and 0.64 (0.32 to 0.84), median 27 months. One- and two-years RC-free survival 0.94 (0.67 to 0.99) and 0.81 (0.52 to 0.94) |

| Milbar et al., 2017 [29] | 33 (22 BCG unresponsive/relapsing) | Retrospective | Gemcitabine Docetaxel |

Induction +/− maintenance | Gemcitabine: inhibition DNA synthesis Docetaxel: inhibition of cell division |

1 and 2 years DFS38% and 24%. One and two years HG-RFS 49% and 34%. |

| Dalbagni et al., 2017 [30] | 19 | Single-arm, phase I/II trial | Gemcitabine Everolimus (oral) |

Gemcitabine induction + everolimus maintenance | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis Everolimus: mTOR inhibition |

3, 6, and 9, 12 months RFS 58% (95% CI 33–76%), 27% (95% CI 9–49%) and 20% (95% CI 5–42%) |

| Robins et al., 2017 [31] | 22 | Single-arm, open-label, phase II trial | Nab-paclitaxel | Induction +/− maintenance | Nab-paclitaxel: inhibition of cell division | Overall CR 36%, non-CIS CR 63, CIS CR 25%. One and three-year RFS 32% and 18% (no CIS CR 40%, CIS CR 10%), |

| Cockerill et al., 2016 [32] | 27 | Retrospective | Gemcitabine MMC |

Induction, no standardized maintenance | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis MMC: inhibition of DNA functions. |

63% recurrence rate, median RFS 15.2 months (range 1.7–32). RFS 37% (median follow-up 22 months) |

| Steinberg et al., 2015 [33] | 45 | Retrospective | Gemcitabine Docetaxel |

Induction +/− maintenance | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis Docetaxel: inhibition of cell division |

Treatment success (no recurrence + no cystectomy) 66% at 12 weeks, 54% at 1 year, 34% at 2 years; median time to failure 3.1 months (range 2.2–25.9) |

| Lightfoot et al., 2014 [34] | 52 (10 BCG naive) | Retrospective | Gemcitabine MMC |

Induction +/− maintenance | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis MMC: inhibition of DNA functions. |

CR 68%, 1- and 2-year RFS, 48%, and 38% |

| McKiernan et al., 2014 [35] | 28 | Single-arm, phase II trial |

Nab-paclitaxel | Induction +/− maintenance | Nab-paclitaxel: inhibition of cell division | 35.7% CR, 1 and 2-year RFS 35.7% and RFS 30.6%. 12, 24, and 36 months CFS 74%, 74%, and 55% |

| Barlow et al., 2013 [36] | 54 | Retrospective | Docetaxel | Induction +/− maintenance | Docetaxel: inhibition of cell division | 59% CR (cystoscopy with biopsy + cytology); 1- and 3-year RFS 40% and 25%; 31% RC rate |

| Skinner et al., 2013 [37] | 58 | Single-arm, open-label, phase II trial | Gemcitabine | Induction +/− maintenance | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis | 3 months CR (negative cystoscopy, urinary cytology +/− biopsy) 47%. Median RFS 6.1 months (95% CI 16–43), 21% at 24 months. Progression/RC rate 36%. |

| Sternberg et al., 2013 [38] | 69 | Retrospective | Gemcitabine | Induction | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis | 5 years progression rate 19% for BCG-refractory pts, 22% for pts with other types of BCG failure (HR 1.09, 95% CI 0.34–3.50). CR (negative cystoscopy and cytology) in 27 pts, PR (negative cystoscopy and positive cytology in 19 with), NR (positive cystoscopy) 20 pts. Subsequent RC in 20 pts |

| Steinberg et al., 2011 [39] | 90 | Single-arm, pivotal phase III open-label study | Valrubicin | Induction | Valrubicin: inhibition of DNA and RNA synthesis | CR in 18 pts at 3 and 6 months (negative cytology, cystoscopy, and biopsy), NR 64 pts |

| McKiernan et al., 2011 [40] | 18 | Phase I trial | Nab-paclitaxel | Induction | Nab-paclitaxel: inhibition of cell division | CR in 5 patients (28%), 13 NR (stage progression in 1) |

| Bassi et al., 2011 [41] | 16 | Single-arm, open-label, phase I trial | Paclitaxel-hyaluronic acid | Induction | Paclitaxel: inhibition of cell division | 6 NR (40%), 9 disease-free pts (60%) |

| Di Lorenzo et al., 2010 [42] | 80 | Multicentric, phase II trial, randomized | Gemcitabine vs. BCG | Induction + maintenance for both arms | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis BCG: stimulating cellular and humoral immune response |

2-year RFS 19% for Gem (95% CI, 5–39), 3% for BCG (95% CI, 0–21; HR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.1–0.3.008). Progression rate 33% for Gem, 37.5% for BCG |

| Perdonà et al., 2010 [43] | 20 | Single-arm, phase II trial | Gemcitabine | Induction + maintenance | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis | 3 months CR at the first 75%; 55% recurrence rate (11 of 20 pts); 45% progression rate (5 of 11 pts) |

| Laudano et al., 2010 [44] | 18 | Single-arm, phase I trial | Docetaxel | Induction | Docetaxel: inhibition of cell division | 22% CR, 17% PR (NMIBC recurrence requiring TURBT with no further treatment), 61% NR (RC or further pharmacologic therapy). PFS 89%. |

| Addeo et al., 2010 [45] | 109 | Phase III trial randomized | Gemcitabine vs. MMC | Induction +/− maintenance for both arms | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis MMC: inhibition of DNA functions. |

RFS in gemcitabine arm, 72% (39 of 54 pts), in MMC arm 61% (33 of 55 pts). Stage progression in 10 pts in the MMC arm and 6 in the gem arm |

| Ignatoff et al., 2009 [46] | 38 | Multicentric, single-arm, phase II trial | AD32 (doxorubicin analog with limited systemic exposure) |

Induction | AD32: inhibition of DNA functions and induction of apoptosis | CR 42.9% (90% CI: 24.5%, 62.8%), CIS CR 23.8% (90% CI: 9.9%, 43.7%). 12 and 24 RFS months 20% (90% CI: 7.8–36.1%) and 15% (CI, 4.9%, 30.2%),12 and 24 CIS RFS 80% (90% CI, 31.4%, 95.8%) if previous CR. PFS 22.4 months, CIS PFS 8.7 months |

| Mohanty et al., 2008 [47] | 35 | Single-arm, non-randomized, phase I trial |

Gemcitabine | Induction | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis | At 18 months follow-up 21 disease free pts (60%), 11 pts (31.4%) with superficial recurrences, 3 (8.75%) with MIBC. Average RFS 12 months, average time to progression 16 months. |

| Gunelli et al., 2007 [48] | 40 | Single-arm, phase II trial |

Gemcitabine | Induction | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis | 95% (38 of 40 pts) CR at 6 months (cystoscopy + cytology); overall event-free survival rate 80% at 1 year and 66% at 2.5 years. At a median follow-up of 28 months, 35% relapse rate (NMIBC). RC in 2 pts |

| Dalbagni et al., 2006 [49] | 30 | Single-arm, phase II trial | Gemcitabine | Induction | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis | 50% CR; median RFS 3.6 months (95% CI, 2.9 to 11.0 months); 21% 1-year RFS in pevious CR (95% CI, 0% to 43%). RC rate 37% |

| McKiernan et al., 2006 [50] | 18 | Single-arm, phase I trial | Docetaxel | Induction | Docetaxel: inhibition of cell division | CR in 56% (10 pts) |

| Bartoletti et al., 2005 [51] | 40 BCG refractory (total population 116) | Multicentric, single-arm, phase II trial | Gemcitabine | Induction | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis | Recurrence rate 32.5%, relapse in 6 (25%) of 24 intermediate-risk BCG refractory pts and 7 (43.7%) of 16 BCG refractory high-risk pts |

| Bassi et al., 2005 [52] | 9 | Single-arm, phase I trial | Gemcitabine | Induction +/− maintenance | Gemcitabine: inhibition of DNA synthesis | CR in 4/9 pts |

| Dalbagni et al., 2002 [53] | 14 | Single-arm, phase I trial | Gemcitabine | Induction (dose levels 500 mg, 1.000 mg, 1.500 mg, and 2.000 mg. | Gemcitabine: inhibition DNA synthesis | CR (defined as a negative posttreatment cystoscopy with biopsy of the urothelium + negative cytology) in 7, failure in 11 (negative bladder biopsy + persistent positive cytology), RC rate 1/11 pts |

Abbreviations are as follows: BCG: Bacillus Calmette–Guerin; CFS: cystectomy-free survival CIS: carcinoma in situ; CR: complete response; CRR: complete response rate; CSM: cancer-specific mortality; CSS: cancer-specific survival; Gem/Doce: gemcitabine/docetaxel; HG: high grade; IFN: interferon; MIBC: muscle-invasive bladder cancer; MMC: mitomycin C; Nab: nanoparticle albumin-bound; NMIBC: non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer; NR: non-responders; OS: overall survival; PFS: progression-free survival; PR: partial response; Pts: patients; RC: radical cystectomy; RFS: recurrence-free survival; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; TRAIL: tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand.

In this scenario, among the chemotherapeutic agents studied, gemcitabine, a deoxycytidine nucleoside analog that can inhibit DNA synthesis and is a cornerstone in the systemic treatment of MIBC in both neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings, may be the one that receives more attention [24]. Gemcitabine has been administered as a single agent by some authors [25][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][51][52][53][25,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,51,52,53], while other series have tested combinations with various other drugs such as docetaxel [25][27][29][33][25,27,29,33], cabazitaxel and cisplatin [28], oral everolimus [30], and mitomycin C (MMC) [32][34][32,34]. Gemcitabine administration regimens are quite heterogeneous in the published literature, with some studies suggesting an induction regimen only [38][47][48][51][53][38,47,48,51,53] and others recommending a maintenance regimen in responders [26][37][42][43][45][52][26,37,42,43,45,52]: no clear and standardized regimen can be found in either single-agent or drug combination studies.

Regarding the oncologic outcomes of intravesical gemcitabine, there is considerable heterogeneity in the assessment of its efficacy and results. In addition, there is a non-negligible discrepancy in study designs, some of which are retrospective. For example, in 2020, Hurle et al. found disease-free survival (DFS) at 12 and 24 months of 44.44% and 31.66%, respectively, in their open-label, single-arm study in which gemcitabine alone was administered to 36 patients in an induction regimen followed by maintenance therapy in responders. In this researchtudy, progression-free survival (PFS) at 12 and 24 months was 80.13% and 69.55%, respectively, while cancer-specific survival (CSS) and overall survival (OS) evaluated at 24 months were 80.68% and 77.9%, respectively [26]. Skinner et al. tested gemcitabine alone in a phase II trial enrolling 58 patients and achieved a CR, i.e., negative cystoscopy, negative urine cytology, and negative biopsy, in 47% of patients at 3 months. The median recurrence-free survival (RFS) was 6.1 months and was still 21% at 24 months, with a progression rate of 36% to RC. In this researchtudy, an induction regimen was used, followed by maintenance therapy in responders [38]. According to the retrospective data of Sternberg et al. on 69 patients treated with gemcitabine induction alone, the 5-year progression to MIBC rate was 19% in BCG-unresponsive patients and 22% in patients with other types of BCG failure. In this series, 27 patients achieved a CR (negative cystoscopy and urinary cytology), 19 achieved a partial response (negative cystoscopy and positive cytology), and 20 patients experienced failure (positive cystoscopy). The cancer-specific death rate was 12% in the complete responders and 18% in the remainder. Subsequent RC had to be performed on 20 patients [38]. Combinations of gemcitabine with other drugs produced different outcomes. According to Chevuru and colleagues, gemcitabine plus docetaxel resulted in an RFS at 12, 24, and 60 months of 57%, 44%, and 24%, respectively, and an HG-RFS at 12, 24, and 60 months of 60%; remarkably, outcomes were slightly worse only in CIS patients compared to papillary disease-only ones [25]. Similar results were found in the retrospective study by Steinberg et al. published in 2020 [27], while the same drug combination performed worse in the study by Milbar [29]. De Castro reported encouraging results by combining gemcitabine with cabazitaxel and cisplatin: The triplet achieved a CR in 89% of cases with a median RFS of 27 months. RC-free survival was 94% at 1 year and 81% at 2 years [28]. The combination with oral Everolimus proposed by Dalbagni resulted in an RFS of 58% at 3 months, 27% at 6 and 9 months, and 20% at 12 months [30]. The association with MMC was tested by Cockerill and Lightfoot. Cockerill determined a recurrence rate of 63% with a median RFS of 15.2 months and a recurrence-free rate of 37% with a final median of 22 months after treatment [32]. Lightfoot found a CR rate and 1-year and 2-year RFS of 68%, 48%, and 38%, respectively [34].

Other drugs such as paclitaxel, nab-paclitaxel [31][40][41][31,40,41], valrubicin, and doxorubicin [33][46][33,46] have been studied with conflicting results. Docetaxel alone resulted in a CR in 56% to 59% of patients [36][40][36,40]. In summary, despite some promising results or at least some effect in certain cases, no definitive conclusion can be drawn regarding intravesical chemotherapy after BCG administration because of the heterogeneity of the studies and protocols and the limited number of patients enrolled in most of these studies.

Intravesical recombinant IFNα-2b protein has been shown to be a well-tolerated molecule in BCG-unresponsive patients [61][101]. Here, intravesical IFNα gene delivery offers a new option for the local treatment of NMIBC by significantly prolonging the duration of exposure to IFNα-2b. Nadofaragene firadenovec (rAd-IFNα/Syn3) consists of rAdIFNα, a non-replicating recombinant adenovirus vector-based gene therapy agent that delivers a copy of the human IFNα-2b gene into the urothelial cell wall [62][63][102,103], while Syn3 is a polyamide surfactant that enhances viral transduction of the urothelium [64][104]. The in vitro reports showed that recombinant IFNα gene therapy led to local IFNα-2b production and was able to induce tumor regression [62][63][102,103]. In a phase II trial, in 40 HG NMIBC patients with BCG-refractory and/or relapsing disease, 35% of the included sample were free of HG recurrence after 12 months [65][95]. Following these encouraging results, Boorjian et al. evaluated 151 BCG-unresponsive patients within a phase III multicenter (33 US Institutions), single-arm, open-label, repeat-dose clinical study. The primary endpoint was any time CR in patients with CIS with or without an HG Ta/T1 NMIBC [66][94]. Overall, 55/103 (53.4%) CIS patients had a CR response within 3 months of the first dose, and this response was maintained in 25/55 (45.5%) of them at 12 months [66][94]. Nadofaragene firadenovec was well tolerated, with no dose-limiting toxicity or clinically significant treatment-related side effects, and a single dose was sufficient to achieve measurable urine IFNα [67][97]. Overall, rAd-IFNα/Syn3 has been evaluated in four single-armed cohort trials [65][66][67][68][94,95,97,98], which found CR rates ranging from 29% to 60% (3 months) and from 29% to 35% (12 months), respectively [6].

It is worth mentioning that in 2018, the FDA granted Fast Track and Breakthrough Therapy status to rAd-IFN/Syn3, and in 2022, this therapy called ALDASTRIN received Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Accelerated Approval, and Priority Review status. Therefore, it is expected to be on the market soon.

CG0070 is a replication-competent oncolytic adenovirus that targets BC cells through their defective retinoblastoma (Rb) signaling pathway, expanding the field of emerging targeted agents. Packiam et al. studied 45 BCG-responsive patients who refused RC and received intravesical CG0070 in the context of a phase II single-arm multicenter trial (NCT02365818). Overall, administration of CG0070 resulted in a CR rate of 47% at 6 months for all patients and 50% for patients with pure CIS [69][96].

Another potential therapeutic option for BCG-unresponsive bladder cancers is BC-819, a double-stranded plasmid with an H19 promoter and a gene encoding for diphtheria toxin-A (dtA). This plasmid is conjugated with polyethyleneimine (in vivo-jetPEI™) to enhance cell transfection. The dtA synthesis is triggered by the transcription factors of H19, an oncofetal riboregulator RNA, which is overexpressed in embryonic tissues and various human tumors. Accordingly, the diphtheria toxin is selectively expressed in cancer cells, leading to blockage of protein synthesis and cell death. Sidi et al. tested the preliminary efficacy and safety of BC-189 in 18 BCG-unresponsive patients with confirmed expression of H19. In 22% (4 out of 18) of patients, tumor markers disappeared completely without the appearance of a new tumor. Monthly maintenance therapy was given to 9 patients, 5 of whom had a disease-free survival (DFS) greater than 35 weeks [70][100].

Intravesical recombinant IFNα-2b protein has been shown to be a well-tolerated molecule in BCG-unresponsive patients [61][101]. Here, intravesical IFNα gene delivery offers a new option for the local treatment of NMIBC by significantly prolonging the duration of exposure to IFNα-2b. Nadofaragene firadenovec (rAd-IFNα/Syn3) consists of rAdIFNα, a non-replicating recombinant adenovirus vector-based gene therapy agent that delivers a copy of the human IFNα-2b gene into the urothelial cell wall [62][63][102,103], while Syn3 is a polyamide surfactant that enhances viral transduction of the urothelium [64][104]. The in vitro reports showed that recombinant IFNα gene therapy led to local IFNα-2b production and was able to induce tumor regression [62][63][102,103]. In a phase II trial, in 40 HG NMIBC patients with BCG-refractory and/or relapsing disease, 35% of the included sample were free of HG recurrence after 12 months [65][95]. Following these encouraging results, Boorjian et al. evaluated 151 BCG-unresponsive patients within a phase III multicenter (33 US Institutions), single-arm, open-label, repeat-dose clinical study. The primary endpoint was any time CR in patients with CIS with or without an HG Ta/T1 NMIBC [66][94]. Overall, 55/103 (53.4%) CIS patients had a CR response within 3 months of the first dose, and this response was maintained in 25/55 (45.5%) of them at 12 months [66][94]. Nadofaragene firadenovec was well tolerated, with no dose-limiting toxicity or clinically significant treatment-related side effects, and a single dose was sufficient to achieve measurable urine IFNα [67][97]. Overall, rAd-IFNα/Syn3 has been evaluated in four single-armed cohort trials [65][66][67][68][94,95,97,98], which found CR rates ranging from 29% to 60% (3 months) and from 29% to 35% (12 months), respectively [6].

It is worth mentioning that in 2018, the FDA granted Fast Track and Breakthrough Therapy status to rAd-IFN/Syn3, and in 2022, this therapy called ALDASTRIN received Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Accelerated Approval, and Priority Review status. Therefore, it is expected to be on the market soon.

CG0070 is a replication-competent oncolytic adenovirus that targets BC cells through their defective retinoblastoma (Rb) signaling pathway, expanding the field of emerging targeted agents. Packiam et al. studied 45 BCG-responsive patients who refused RC and received intravesical CG0070 in the context of a phase II single-arm multicenter trial (NCT02365818). Overall, administration of CG0070 resulted in a CR rate of 47% at 6 months for all patients and 50% for patients with pure CIS [69][96].

Another potential therapeutic option for BCG-unresponsive bladder cancers is BC-819, a double-stranded plasmid with an H19 promoter and a gene encoding for diphtheria toxin-A (dtA). This plasmid is conjugated with polyethyleneimine (in vivo-jetPEI™) to enhance cell transfection. The dtA synthesis is triggered by the transcription factors of H19, an oncofetal riboregulator RNA, which is overexpressed in embryonic tissues and various human tumors. Accordingly, the diphtheria toxin is selectively expressed in cancer cells, leading to blockage of protein synthesis and cell death. Sidi et al. tested the preliminary efficacy and safety of BC-189 in 18 BCG-unresponsive patients with confirmed expression of H19. In 22% (4 out of 18) of patients, tumor markers disappeared completely without the appearance of a new tumor. Monthly maintenance therapy was given to 9 patients, 5 of whom had a disease-free survival (DFS) greater than 35 weeks [70][100].

3. Chemo-Hyperthermia

The effect of hyperthermia on tumor cells has been known for decades, and several effects of hyperthermia have been described to date. First, at temperatures above 40.5 °C and above, ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) synthesis is reduced, and DNA repair itself is impaired [54]. In addition, hyperthermia can alter tumor blood flow in several ways. Up to a temperature of 43 °C, vasodilatation is observed, which allows better delivery of chemotherapeutic agents. Moreover, direct damage such as occlusion and destruction of the endothelial cells lining the tumor vessels, which have a reduced ability to dissipate heat compared to normal tissue, has been described, resulting in decreased blood flow to the cancer cells [55]. In turn, the cancer microenvironment becomes increasingly hypoxic, and cancer cells become more sensitive to both heat and chemotherapy, while angiogenesis is inhibited via the upregulation of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 pathway in endothelial cells of the tumor vasculature [55]. In addition, hyperthermia mimics the physiological mechanisms occurring in the immune system during fever, such as the activation of CD8 and CD4 immune cells, the infiltration of NK cells, and the production of heat shock proteins and cytokines, thus facilitating the activation of many molecular effectors of the immune system [56].4. Immunotherapy and Inflammation-Targeted Agents

In the field of immunotherapy for both MIBC and UTUC, pembrolizumab has played an increasingly important role in recent years [11][57][11,66]. Pembrolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody against programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), a so-called immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI). PD-1 is a transmembrane receptor that binds to two different ligands: Programmed cell death protein 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) and ligand 2 (PD-L2). PD-1 is expressed by activated CD4C and CD8C T cells, B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells, whereas PD-L1 is constitutively expressed on T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, regulatory T cells (Treg), monocytes, and macrophages. Binding of PD-1 to its ligands PD-L1 and 2 results in an inhibitory transduction signal for T cells. Taking advantage of this mechanism, tumor cells express PD-L1 and thus evade the immune response. By binding PD-1 and preventing interaction with its ligands, pembrolizumab may enhance the anti-tumor immune response [58][67]. In light of this, some studies have attempted to evaluate the efficacy of pembrolizumab in BCG-refractory NMIBC. In such reports, pembrolizumab has been administered in combination with BCG by both intravesical [59][68] and intravenous routes and as a single agent [58][67].5. Gene Therapy

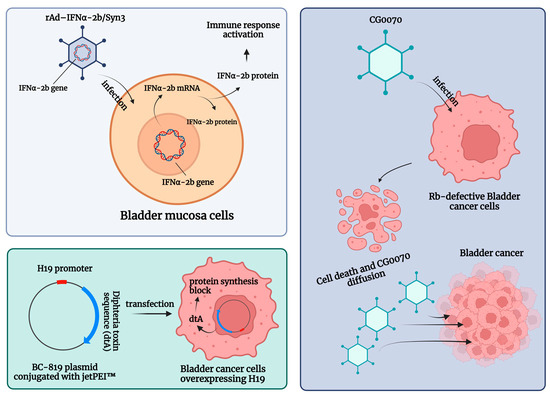

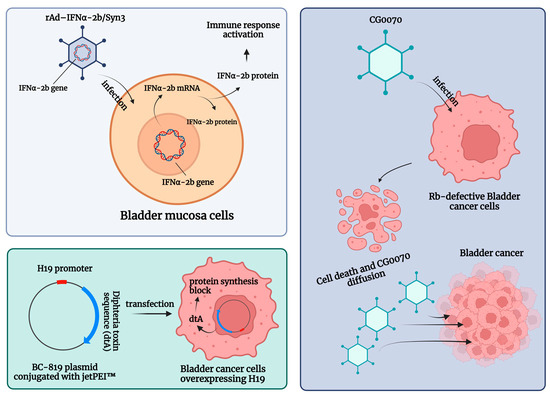

Genetic instability is an essential early step in the development of BC [60][93]. Such instability is easily detected at both the chromosomal and nucleotide levels. Consequently, microsatellite and chromosomal instability can be used as prognostic markers for BC, and previous experiences have shown that specific mutations are associated with a higher probability of progression and poorer survival after RC. In such a rapidly evolving tumor microenvironment (TME), genotypic and phenotypic alternations that can modulate gene and protein expression are critical for tumor invasion and the development of tumor escape mechanisms. A schematic summary of the gene therapies described is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Schematic summary of the gene therapies for patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma (NMIBC) unresponsive to Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) treatment. Abbreviations are as follows: dtA: diphtheria toxin; IFN: interferon; jetPEI™: polyethyleneimine; rAd-IFNα/Syn3: Nadofaragene firadenovec. The image was created with BioRender.com.