Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Fanny Huang and Version 1 by Pinqiu Chen.

Various factors contribute to sleep deprivation (SD) in the modern world, and these include alcohol consumption, shifting work, exposure to excessive light and noise, stress, anxiety, and certain medical conditions. Insomnia, narcolepsy, restless leg syndrome, and obstructive sleep apnea are some of the manifestations of SD. Numerous studies have examined the effects of SD on memory, with the majority showing that sleep disorders negatively affect memory.

- sleep deprivation

- memory impairment

- hippocampus

- brain

- insonmia

1. Introduction

Various factors contribute to SD in the modern world, and these include alcohol consumption, shifting work, exposure to excessive light and noise, stress, anxiety, and certain medical conditions. Insomnia, narcolepsy, restless leg syndrome, and obstructive sleep apnea are some of the manifestations of SD. It is experienced by many people to varying degrees. More than one-third of the global population suffers from insomnia, with prevalence rates ranging from 23.2% to 27.1% [1]. Additionally, the insomnia rate has increased to 29.7–58.4% during the epidemic [2]. Overall, the prevalence is higher in Asian and European regions, especially in East Asia, where it is about 27% [1,3][1][3]. In China, about 38% of the population suffers from various types of SD, and this rate is higher than the world average of 27%. Nearly half of older adults aged more than 60 years have experienced SD. More than a third of American adults have less than 6 h (h) of sleep per night. People with SD are more likely to develop diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, chronic kidney disease, and Alzheimer’s disease by up to two to three times more than those without SD [4]. Encoding, consolidation, and retrieval are the three stages of memory formation [5,6][5][6]. During sleep, memory functions, including spatial memory, memory recognition, long-term memory, short-term memory, and prospective memory, are maintained and strengthened. Several studies suggest that SD can decrease hippocampal activation during the encoding phase while in the awake period, resulting in impaired memory retrieval even after one night of recovery sleep [7]. Total SD negatively affects their ability to form trace-conditioned memories [8]. Memory has been shown to be highly affected by SD. As a result of SD, patients have varying degrees of impairment in their prospective and spatial memory [9,10,11,12,13][9][10][11][12][13]. Memory impairment due to SD is a hot and difficult issue in current research. SD can result in memory impairment through a variety of mechanisms, but few studies have attempted to systematically and purposefully summarize the underlying mechanisms. Therefore, clarifying the substantive effect of SD on memory is extremely critical. A few studies reported that SD may improve memory, but others stated that SD increases the risk of various diseases and negatively affects learning and memory [14,15,16,17][14][15][16][17].

2. Impaired Memory Function

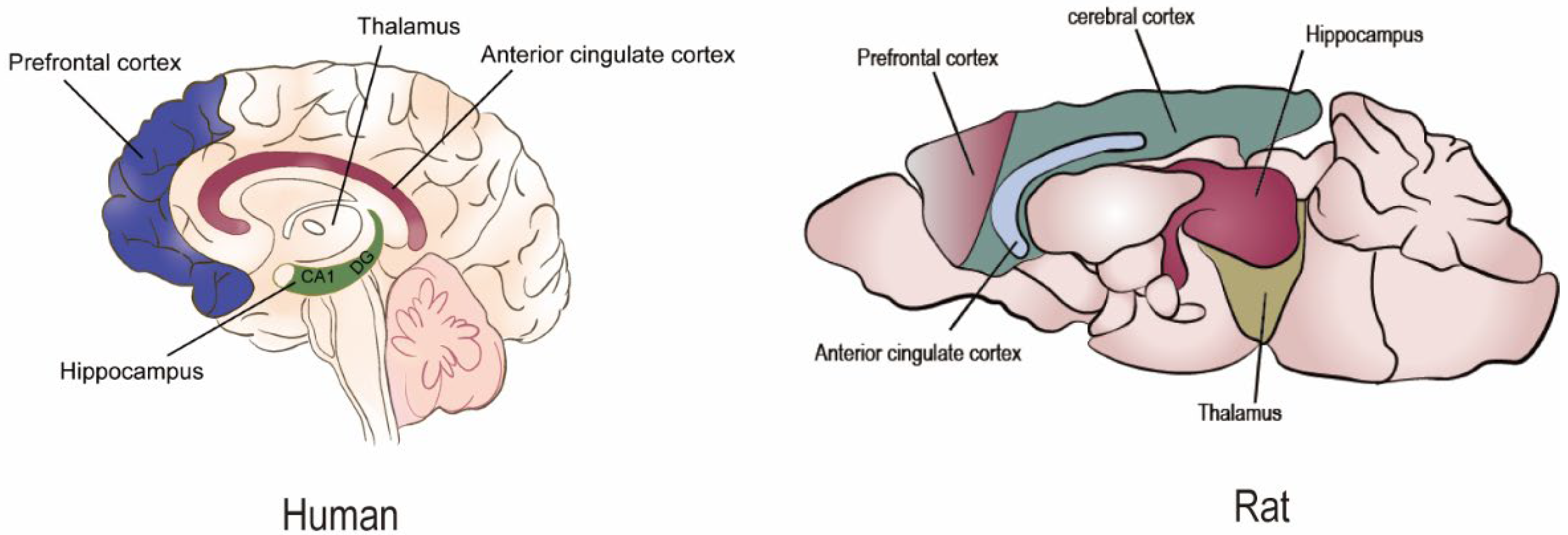

Insomnia is the most prevalent type of sleep disorder and is characterized by a high rate of morbidity and mortality, as well as high social costs. A growing body of evidence suggests that sleep plays a critical role in memory because it is a normal physiological process and a crucial brain function [18]. Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and dementia are all associated with SD. Several areas of the brain damaged by SD include the hippocampus, thalamus, prefrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex (Figure 1). The hippocampus is responsible for the processing, consolidation, and retrieval of short- and long-term memory and for spatial navigation and orientation [6,19][6][19]. Proteins that are linked to the hippocampus are crucially involved in memory formation [20]. SD could induce damages to hippocampal neurons and reduce the size and volume of the hippocampus, impairing hippocampal-dependent memory functions and resulting in difficulties in recalling past events and forming new memories [21]. SD can affect hippocampal function at the molecular level by decreasing encoding-related activity within the hippocampus [22]. The thalamus is involved in regulating sleep–wake cycles during SD and emotional processing [23]. Similarly, SD can lead to decreased activity in the thalamus, resulting in impaired sensory perception and processing [24]. The encoding of working memory relies on the prefrontal cortex, which plays a crucial role in attention and memory [25,26][25][26]. Reduced prefrontal cortex activity caused by SD can impair cognitive function, including attention, working memory, and fear memory consolidation [27,28][27][28]. The anterior cingulate cortex modulates the frontoparietal functional connectivity between resting-state and working memory tasks [29]. Additionally, SD can cause decreased anterior cingulate cortex activity, leading to impaired emotional regulation and decision-making abilities [30,31][30][31]. Insomnia is often associated with a decline in memory function, indicating a strong connection between insomnia and memory loss.

Figure 1. The main brain areas affected by sleep deprivation in humans and rodents.

SD has been reported to negatively affect memory in animal models and humans [32,33][32][33]. It can impair spatial working memory in humans [34], as well as in young rats after 24 h of SD [35]. SD with 4–6 weeks of chronic rapid eye movement sleep (REM) can affect hippocampal spatial memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory in Wister rats [36,37,38][36][37][38]. The induction of short- and long-term memory in Aplysia was inhibited by 9 h/12 h SD [39]. The short- and long-term memory was significantly impaired by SD in rats and sea rabbits [40,41][40][41]. Additionally, prospective memory and declarative memory are also affected by SD [13[13][42],42], resulting in attenuation of weakly encoded memories in humans [43] and impaired encoding of trace memory in rats [8]. Although SD has a great effect on the memory function of older individuals [44], healthy young men experienced impaired working memory after 16 h of total SD [45]. After total SD with multiplatform and mild stimulation, EPM-M1 male mice developed memory deficits in the plus-maze discriminative avoidance task and passive avoidance dance task. REM SD for 72 h impaired novelty-related object site memory in mice [46]. In a study using C57BL/6J mice, a mild stimulus method of SD was used to train them for 1 h on a location recognition task, which significantly impaired memory function after only 3 h [47]. When flies were exposed to 4 h of SD during the consolidation phase, their memory was disrupted [48]. Memory function is also impaired in Octodon degus [49] and zebrafish [50]. Multiple animal models demonstrated the effects of SD on memory. Memory processing is severely affected by acute or chronic SD (Table 1).

Table 1. Memory function and SD: harmful effects.

| Subject | Methods | SD Duration |

Behavioral Tests | Impaired Memory | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humanity | Staying awake | 25 h | Recognition test | Prospective memory Recognition memory |

[13] |

| ICR mice | SIA | 25 d | OLR, NOR, MWM | Short-term spatial and short-term nonspatial recognition memory; long-term spatial memory | [9] |

| C57BL/6 mice | Treadmill | 3 d | MWM | Spatial memory | [51] |

| C57BL/6 mice | MMPM | 72 h | OLR, NOR | Object position memory Object recognition memory |

[52] |

| C57BL/6 mice | Gentle stimulation method | 3 h | OPR | Long-term memory | [47] |

| 3xTg-AD mice | MMPM | 21 d | Y-maze Object identification |

Recognition of memories Working memory Conditioned Fear Memory Y-maze memory |

[32] |

| Mice | MMPM | 72 h | Barnes maze task | Spatial learning and memory | [40] |

| SD rat | MMWP | 7 d | Hexagonal Labyrinth Box | Recognition of memory | [53] |

| SD rat | Small platform–water environment |

9 d | Small platform–water environment |

Memory | [54] |

| SD rat | MMPM | 7 d | MWM | Spatial memory | [55] |

| SD rat | Chronic and mild unpredictable stimulation | 21 d | RAWM | Target quadrant memory | [56] |

| SD rat | MMPM | 30 d | MWM | Memories of learning | [57] |

| SD rat | Automated cage-shaking apparatus | 48 h | MWM | Spatial memory | [57] |

| SD rat | Gentle stimulation method | 72 h | MWM | Spatial memory | [57] |

| SD rat | MMPM | 72 h | Y-maze MWM |

Spatial memory Recognition of memories Recognition of memories |

[34] |

| SD rat | Gentle stimulation method | 12 h | NOR, RAM | Spatial learning and memory | [35] |

| SD rat | Automatic TSD water box | 24 h | The three-chamber paradigm test | Social interaction memory | [58] |

| Octodon degus | Automated device | 24 h | MWM, NOR | Spatial learning and memory | [49] |

| Wistar rats | MMW | 21 d | RAWM | Short- and long-term spatial memory | [37] |

| Wistar rats | MMPM | 28 d | RAWM | Short- and long-term memory | [59] |

| Wistar rats | “Flower pot” | 96 h | MWM | Memories of learning | [60] |

OLR = object location recognition; NOR = novel object recognition; MWM = Morris water maze; SIA = automated sleep interruption apparatus; MMW = modified multi-platform–water environment; OPR = object place recognition.

References

- Ding, C.; Wu, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lin, Z.; Kang, D.; Fang, W.; Chen, F. Global, regional, and national burden and attributable risk factors of neurological disorders: The Global Burden of Disease study 1990–2019. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 952161.

- Yuan, K.; Zheng, Y.B.; Wang, Y.J.; Sun, Y.K.; Gong, Y.M.; Huang, Y.T.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.X.; Zhong, Y.; Su, S.Z.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on prevalence of and risk factors associated with depression, anxiety and insomnia in infectious diseases, including COVID-19: A call to action. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 3214–3222.

- Chowdhury, A.I.; Ghosh, S.; Hasan, M.F.; Khandakar, K.A.S.; Azad, F. Prevalence of insomnia among university students in South Asian Region: A systematic review of studies. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2020, 61, e525–e529.

- Hung, C.M.; Li, Y.C.; Chen, H.J.; Lu, K.; Liang, C.L.; Liliang, P.C.; Tsai, Y.D.; Wang, K.W. Risk of dementia in patients with primary insomnia: A nationwide population-based case-control study. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 38.

- Creery, J.D.; Brang, D.J.; Arndt, J.D.; Bassard, A.; Towle, V.L.; Tao, J.X.; Wu, S.; Rose, S.; Warnke, P.C.; Issa, N.P.; et al. Electrophysiological markers of memory consolidation in the human brain when memories are reactivated during sleep. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2123430119.

- Crowley, R.; Bendor, D.; Javadi, A.H. A review of neurobiological factors underlying the selective enhancement of memory at encoding, consolidation, and retrieval. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019, 179, 101615.

- Yoo, S.S.; Hu, P.T.; Gujar, N.; Jolesz, F.A.; Walker, M.P. A deficit in the ability to form new human memories without sleep. Nat. Neurosci. 2007, 10, 385–392.

- Chowdhury, A.; Chandra, R.; Jha, S.K. Total sleep deprivation impairs the encoding of trace-conditioned memory in the rat. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2011, 95, 355–360.

- Lu, C.; Lv, J.; Jiang, N.; Wang, H.; Huang, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Zhang, N.; Fan, B.; Liu, X.; et al. Protective effects of Genistein on the cognitive deficits induced by chronic sleep deprivation. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 846–858.

- Esposito, M.J.; Occhionero, M.; Cicogna, P. Sleep Deprivation and Time-Based Prospective Memory. Sleep 2015, 38, 1823–1826.

- Menz, M.M.; Rihm, J.S.; Salari, N.; Born, J.; Kalisch, R.; Pape, H.C.; Marshall, L.; Büchel, C. The role of sleep and sleep deprivation in consolidating fear memories. Neuroimage 2013, 75, 87–96.

- Cipolli, C.; Mazzetti, M.; Plazzi, G. Sleep-dependent memory consolidation in patients with sleep disorders. Sleep Med. Rev. 2013, 17, 91–103.

- Grundgeiger, T.; Bayen, U.J.; Horn, S.S. Effects of sleep deprivation on prospective memory. Memory 2014, 22, 679–686.

- Cho, J.W.; Duffy, J.F. Sleep, Sleep Disorders, and Sexual Dysfunction. World J. Men’s Health 2019, 37, 261–275.

- Clark, A.J.; Salo, P.; Lange, T.; Jennum, P.; Virtanen, M.; Pentti, J.; Kivimäki, M.; Rod, N.H.; Vahtera, J. Onset of Impaired Sleep and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: A Longitudinal Study. Sleep 2016, 39, 1709–1718.

- Sumowski, J.F.; Horng, S.; Brandstadter, R.; Krieger, S.; Leavitt, V.M.; Katz Sand, I.; Fabian, M.; Klineova, S.; Graney, R.; Riley, C.S.; et al. Sleep disturbance and memory dysfunction in early multiple sclerosis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2021, 8, 1172–1182.

- Zhu, B.; Dong, Y.; Xu, Z.; Gompf, H.S.; Ward, S.A.; Xue, Z.; Miao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chamberlin, N.L.; Xie, Z. Sleep disturbance induces neuroinflammation and impairment of learning and memory. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012, 48, 348–355.

- Newbury, C.R.; Crowley, R.; Rastle, K.; Tamminen, J. Sleep deprivation and memory: Meta-analytic reviews of studies on sleep deprivation before and after learning. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 147, 1215–1240.

- Xu, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Jia, C. Phosphoproteomic analysis reveals the effects of sleep deprivation on the hippocampus in mice. Mol. Omics 2022, 18, 677–685.

- Aijuan, T.; Anding, D.; Mengmeng, Z.; Shiming, L.; Guili, Y. The role of c-fos gene in the enhancement of memory in the hippocampus of mouse. J. Yangzhou Univ. 2022, 43, 67–72.

- Zhou, H.; Wu, J.; Gong, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J. Isoquercetin alleviates sleep deprivation dependent hippocampal neurons damage by suppressing NLRP3-induced pyroptosis. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2022, 44, 766–772.

- Krause, A.J.; Simon, E.B.; Mander, B.A.; Greer, S.M.; Saletin, J.M.; Goldstein-Piekarski, A.N.; Walker, M.P. The sleep-deprived human brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 404–418.

- Li, B.Z.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Y.H.; Peng, J.X.; Shao, Y.C.; Zhang, X. Relation of Decreased Functional Connectivity Between Left Thalamus and Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus to Emotion Changes Following Acute Sleep Deprivation. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 642411.

- Chen, Y.; Pan, L.; Ma, N. Altered effective connectivity of thalamus with vigilance impairments after sleep deprivation. J. Sleep Res. 2022, 31, e13693.

- Bahmani, Z.; Clark, K.; Merrikhi, Y.; Mueller, A.; Pettine, W.; Isabel Vanegas, M.; Moore, T.; Noudoost, B. Prefrontal Contributions to Attention and Working Memory. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 41, 129–153.

- Dixsaut, L.; Gräff, J. The Medial Prefrontal Cortex and Fear Memory: Dynamics, Connectivity, and Engrams. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12113.

- Feng, P.; Becker, B.; Zheng, Y.; Feng, T. Sleep deprivation affects fear memory consolidation: Bi-stable amygdala connectivity with insula and ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2018, 13, 145–155.

- Chauveau, F.; Laudereau, K.; Libourel, P.A.; Gervasoni, D.; Thomasson, J.; Poly, B.; Pierard, C.; Beracochea, D. Ciproxifan improves working memory through increased prefrontal cortex neural activity in sleep-restricted mice. Neuropharmacology 2014, 85, 349–356.

- Di, X.; Zhang, H.; Biswal, B.B. Anterior cingulate cortex differently modulates frontoparietal functional connectivity between resting-state and working memory tasks. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020, 41, 1797–1805.

- Zhang, L.; Shao, Y.; Jin, X.; Cai, X.; Du, F. Decreased effective connectivity between insula and anterior cingulate cortex during a working memory task after prolonged sleep deprivation. Behav. Brain Res. 2021, 409, 113263.

- Noorafshan, A.; Karimi, F.; Karbalay-Doust, S.; Kamali, A.M. Using curcumin to prevent structural and behavioral changes of medial prefrontal cortex induced by sleep deprivation in rats. EXCLI J. 2017, 16, 510–520.

- Chun, W.; Xu, C.; Jing, Y.; Wen-Rui, G.; Wei-Ran, L.; Jin-Shun, Q.; Mei-Na, W. Chronic sleep deprivation exacerbates cognitive and pathological impairments inAPP/PS1/tau triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease model mice. Acta Physiol. Sin. 2021, 73, 471–481.

- Zare Khormizi, H.; Salehinejad, M.A.; Nitsche, M.A.; Nejati, V. Sleep-deprivation and autobiographical memory: Evidence from sleep-deprived nurses. J. Sleep Res. 2019, 28, e12683.

- Hennecke, E.; Lange, D.; Steenbergen, F.; Fronczek-Poncelet, J.; Elmenhorst, D.; Bauer, A.; Aeschbach, D.; Elmenhorst, E.M. Adverse interaction effects of chronic and acute sleep deficits on spatial working memory but not on verbal working memory or declarative memory. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13225.

- Ward, C.P.; Wooden, J.I.; Kieltyka, R. Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Spatial Learning and Memory in Juvenile and Young Adult Rats. Psychol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 109–116.

- Mhaidat, N.M.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Khabour, O.F.; Tashtoush, N.H.; Banihani, S.A.; Abdul-razzak, K.K. Exploring the effect of vitamin C on sleep deprivation induced memory impairment. Brain Res. Bull. 2015, 113, 41–47.

- Massadeh, A.M.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Milhem, A.M.; Rababa’h, A.M.; Khabour, O.F. Evaluating the effect of selenium on spatial memory impairment induced by sleep deprivation. Physiol. Behav. 2022, 244, 113669.

- Alzoubi, K.H.; Al Mosabih, H.S.; Mahasneh, A.F. The protective effect of edaravone on memory impairment induced by chronic sleep deprivation. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 281, 112577.

- Krishnan, H.C.; Noakes, E.J.; Lyons, L.C. Chronic sleep deprivation differentially affects short and long-term operant memory in Aplysia. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2016, 134 Pt B, 349–359.

- Salehpour, F.; Farajdokht, F.; Erfani, M.; Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Shotorbani, S.S.; Hamblin, M.R.; Karimi, P.; Rasta, S.H.; Mahmoudi, J. Transcranial near-infrared photobiomodulation attenuates memory impairment and hippocampal oxidative stress in sleep-deprived mice. Brain Res. 2018, 1682, 36–43.

- Krishnan, H.C.; Gandour, C.E.; Ramos, J.L.; Wrinkle, M.C.; Sanchez-Pacheco, J.J.; Lyons, L.C. Acute Sleep Deprivation Blocks Short- and Long-Term Operant Memory in Aplysia. Sleep 2016, 39, 2161–2171.

- Cousins, J.N.; Fernández, G. The impact of sleep deprivation on declarative memory. Prog. Brain Res. 2019, 246, 27–53.

- Baena, D.; Cantero, J.L.; Fuentemilla, L.; Atienza, M. Weakly encoded memories due to acute sleep restriction can be rescued after one night of recovery sleep. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1449.

- Liu, X.; Peng, X.; Peng, P.; Li, L.; Lei, X.; Yu, J. The age differences of sleep disruption on mood states and memory performance. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1444–1451.

- Sauvet, F.; Arnal, P.J.; Tardo-Dino, P.E.; Drogou, C.; Van Beers, P.; Erblang, M.; Guillard, M.; Rabat, A.; Malgoyre, A.; Bourrilhon, C.; et al. Beneficial effects of exercise training on cognitive performances during total sleep deprivation in healthy subjects. Sleep Med. 2020, 65, 26–35.

- Patti, C.L.; Zanin, K.A.; Sanday, L.; Kameda, S.R.; Fernandes-Santos, L.; Fernandes, H.A.; Andersen, M.L.; Tufik, S.; Frussa-Filho, R. Effects of sleep deprivation on memory in mice: Role of state-dependent learning. Sleep 2010, 33, 1669–1679.

- Prince, T.M.; Wimmer, M.; Choi, J.; Havekes, R.; Aton, S.; Abel, T. Sleep deprivation during a specific 3-hour time window post-training impairs hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2014, 109, 122–130.

- Le Glou, E.; Seugnet, L.; Shaw, P.J.; Preat, T.; Goguel, V. Circadian modulation of consolidated memory retrieval following sleep deprivation in Drosophila. Sleep 2012, 35, 1377–1384.

- Estrada, C.; Fernández-Gómez, F.J.; López, D.; Gonzalez-Cuello, A.; Tunez, I.; Toledo, F.; Blin, O.; Bordet, R.; Richardson, J.C.; Fernandez-Villalba, E.; et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and aging: Effects on spatial learning and memory after sleep deprivation in Octodon degus. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2015, 125, 274–281.

- Lv, D.J.; Li, L.X.; Chen, J.; Wei, S.Z.; Wang, F.; Hu, H.; Xie, A.M.; Liu, C.F. Sleep deprivation caused a memory defects and emotional changes in a rotenone-based zebrafish model of Parkinson’s disease. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 372, 112031.

- Xiong, X.; Zuo, Y.; Cheng, L.; Yin, Z.; Hu, T.; Guo, M.; Han, Z.; Ge, X.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; et al. Modafinil Reduces Neuronal Pyroptosis and Cognitive Decline After Sleep Deprivation. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 816752.

- Jiao, Q.; Dong, X.; Guo, C.; Wu, T.; Chen, F.; Zhang, K.; Ma, Z.; Sun, Y.; Cao, H.; Tian, C.; et al. Effects of sleep deprivation of various durations on novelty-related object recognition memory and object location memory in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 418, 113621.

- Yan-yan, W.; Hong-sheng, B.; Hai-ni, L.; Yu-fei, C.; Wen-wen, L.; Ting-li, L.; Li-li, H. Effects of L-tetrahydropalmatine on learning and memory, and sleep rhythm in rats with rapid eye movement sleep deprivation. Chin. Tradit. Pat. Med. 2022, 44, 2812–2817.

- Qianwei, Y.; Xingping, Z.; Deqi, Y.; Kaikai, W.; Zhenpeng, T.; Ning, D. Expression differences of orexin receptors in related organs of insomnia rats with lung storing no inferior spirit. Shanghai J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2022, 56, 75–80.

- Hu, Y.; Yin, J.; Yang, G. Melatonin upregulates BMAL1 to attenuate chronic sleep deprivation-related cognitive impairment by alleviating oxidative stress. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e2836.

- Tianshan, B.; Zhirong, L.; Ping, H.; Ye, X.; Wenhua, L. The Ameliorating Effect of Venlafaxine on the Depressive Symptoms of Depression Model Rats and Its Effect on Pl3K/Akt/mTORC1 Signaling Pathway in Hippocampus. Chin. J. Integr. Med. Cardio-Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 19, 2348–2352.

- Wadhwa, M.; Kumari, P.; Chauhan, G.; Roy, K.; Alam, S.; Kishore, K.; Ray, K.; Panjwani, U. Sleep deprivation induces spatial memory impairment by altered hippocampus neuroinflammatory responses and glial cells activation in rats. J. Neuroimmunol. 2017, 312, 38–48.

- Almaspour, M.B.; Nasehi, M.; Khalifeh, S.; Zarrindast, M.R. The effect of fish oil on social interaction memory in total sleep-deprived rats with respect to the hippocampal level of stathmin, TFEB, synaptophysin and LAMP-1 proteins. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fat. Acids 2020, 157, 102097.

- Alzoubi, K.H.; Mayyas, F.A.; Khabour, O.F.; Bani Salama, F.M.; Alhashimi, F.H.; Mhaidat, N.M. Chronic Melatonin Treatment Prevents Memory Impairment Induced by Chronic Sleep Deprivation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 3439–3447.

- Ocalan, B.; Cakir, A.; Koc, C.; Suyen, G.G.; Kahveci, N. Uridine treatment prevents REM sleep deprivation-induced learning and memory impairment. Neurosci. Res. 2019, 148, 42–48.

More