Spermatocytic tumor (ST) is a very rare disease, accounting for approximately 1% of testicular cancers. Previously classified as spermatocytic seminoma, it is currently classified within the non-germ neoplasia in-situ-derived tumors and has different clinical-pathologic features when compared with other forms of germ cell tumors (GCTs). A web-based search of MEDLINE/PubMed library data was performed in order to identify pertinent articles. In the vast majority of cases, STs are diagnosed at stage I and carry a very good prognosis. The treatment of choice is orchiectomy alone. Nevertheless, there are two rare variants of STs having very aggressive behavior, namely anaplastic ST and ST with sarcomatous transformation, that are resistant to systemic treatments and their prognosis is very poor.

- spermatocytic tumor

- rare tumors

- germ cell tumors

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology

ST is a rare testis tumor, accounting for about 1% of all testicular tumors [9][6]. Although its incidence has been reported at around 52–56 years of age, it has never been considered as a tumor of the elderly population [6,9,10,11,12][4][6][7][8][9]. Nearly 70% of patients are over 40 years of age, and it is virtually absent in children, adolescents and young adults, although the youngest patient described in the literature was 19 years old [9][6]. In an Australian series among 9658 cases of primary testicular tumors in the period 1982–2002, only 58 cases of STs were reported, and the Australian age-standardized incidence rate for spermatocytic seminoma was 0.4 cases per million. The mean number of cases diagnosed per year was 2.8, ranging from 0 to 7. In particular, the standardized incidence was 0.3 cases per million for men younger than 55 and 0.8 per million for men 55 years or older [9][6]. The mean patient age at diagnosis was 53.5 years, 50% of men were diagnosed at 54 years or younger, and approximately 25% of patients were younger than 40 years [9][6]. This cohort of patients reported not only the youngest patients with ST (19 years old), but also the oldest patient reported in literature, who was 92 years old [9][6]. In addition, the Australian series detected no statistical increase in the incidence of STs in the previous 20 years, but the ability of the authors to identify trends was limited by the small number of cases available [9][6].3. Pathophysiology

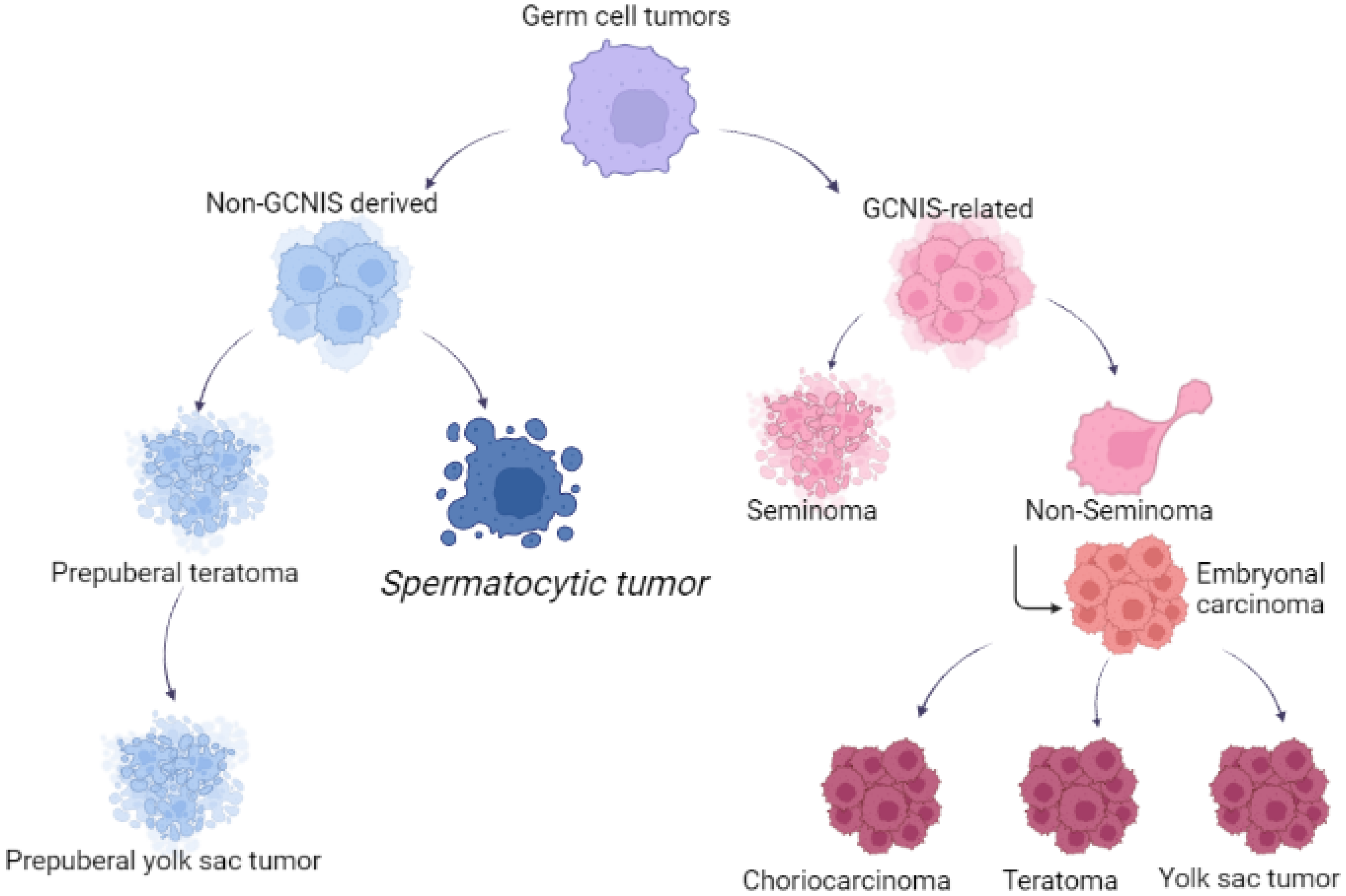

Spermatocytic tumor was considered closely related to seminoma and classified as subtype of this disease from the time of its first description in 1946 by Masson, who named this entity as “le seminome spermatocitaire” [16][10]. The reason for the WHO classification change [4][2] was due to several important differences. First, STs have a different origin compared with other GCTs: they derive from more mature germ cells (likely premeiotic germ cells at a transition stage between spermatogonia and spermatocytes), in contrast to postpubertal-type germ cell tumors such as seminoma, which are thought to originate from primordial germ cells/gonocytes. Increased recognition of this distinction led to a revision in the nomenclature of these tumors from spermatocytic seminoma to ST, particularly to avoid overlapping terminology with GCNIS-derived seminoma. Second, unlike seminoma, STs do not exhibit gains of the short arm of chromosome 12, which is a frequent finding in (GCNIS-derived) postpuberal type germ cell tumors [17,18][11][12]. Third, STs show a unique amplification of chromosome 9, corresponding to the DMRT1 gene, not reported in all GCNIS-related tumors, but also in prepuberal teratoma and prepuberal YST [19][13]. The DMRT1 gene, located at the end of the 9th chromosome, is found in a cluster with two other members of the gene family (DMRT2, DMRT3), having in common a zinc finger-like DNA-binding motif (DM domain). The DMRT1 protein is located in the spermatogonia and in the spermatocytes, specifically in the nucleus, and its role is critical during embryogenesis and male germ cell maturation. Figure 1 reported the different origins of GCTs and STs.

4. Histopathology

4. Histopathology

5. Clinical Features

STs usually present with a unilateral mass. Bilateral involvement has been reported, even though is more often documented in ST compared with other germ cell tumors [11,25,28,29]. One of the large series published showed bilateral STs in 5% of testicular tumor; one patient (1%) had synchronous bilateral mass in undescended testes at age 67, and 2 patients (3%) had metachronous bilateral testicular masses at intervals of 10 and 16 years, respectively [11].6. Treatment

Surgical orchiectomy is the standard treatment for STs, as testis-sparing techniques are limited by the difficulties for the pathologist in differentiating ST from seminoma GCT in a frozen section [29]. As STs rarely metastasize, surgery alone is the standard of care. In the past, adjuvant radiotherapy was performed, but it has gone into disrepute in recent studies [5][30]. The US study also compared survival outcomes for men with ST relative to classic seminoma. After adjusting for differences in baseline demographics, such as age and comorbidity, as well as stage distribution, they observed no differences in overall survival between the two groups [9]. The favorable survival outcomes for ST, despite a reduction in the use of adjuvant therapy after orchiectomy over time, is encouraging. On the other hand, STs with sarcoma transformation or anaplastic subtypes showed metastatic disease in 45% and 29% of cases, respectively; compared to ST, patients having these histological variants were more likely to have metastatic disease. These subtypes are highly resistant to cytotoxic chemotherapy and they represent a very aggressive disease: patients have a poor prognosis, with a median survival of 5 months [26][31]. Despite the high risk of metastases, the guideline of treatment for STs with sarcomatous transformation has yet to be established, albeit adjuvant chemotherapy seems to be a possible choice. In the literature, five of these patients received platinum-based chemotherapy, and all responded poorly and died shortly (within 3–14 months) after diagnosis [9]. However, only one case of metastatic ST responded well to the VIP combination chemotherapy after radical orchiectomy [32].6. Treatment

Surgical orchiectomy is the standard treatment for STs, as testis-sparing techniques are limited by the difficulties for the pathologist in differentiating ST from seminoma GCT in a frozen section [37]. As STs rarely metastasize, surgery alone is the standard of care. In the past, adjuvant radiotherapy was performed, but it has gone into disrepute in recent studies [7,38]. The US study also compared survival outcomes for men with ST relative to classic seminoma. After adjusting for differences in baseline demographics, such as age and comorbidity, as well as stage distribution, they observed no differences in overall survival between the two groups [12]. The favorable survival outcomes for ST, despite a reduction in the use of adjuvant therapy after orchiectomy over time, is encouraging. On the other hand, STs with sarcoma transformation or anaplastic subtypes showed metastatic disease in 45% and 29% of cases, respectively; compared to ST, patients having these histological variants were more likely to have metastatic disease. These subtypes are highly resistant to cytotoxic chemotherapy and they represent a very aggressive disease: patients have a poor prognosis, with a median survival of 5 months [31,41]. Despite the high risk of metastases, the guideline of treatment for STs with sarcomatous transformation has yet to be established, albeit adjuvant chemotherapy seems to be a possible choice. In the literature, five of these patients received platinum-based chemotherapy, and all responded poorly and died shortly (within 3–14 months) after diagnosis [12]. However, only one case of metastatic ST responded well to the VIP combination chemotherapy after radical orchiectomy [42].References

- Moch, H.; Amin, M.B.; Berney, D.M.; Comperat, E.M.; Gill, A.J.; Hartmann, A.; Menon, S.; Raspollini, M.R.; Rubin, M.A.; Srigley, J.R.; et al. The 2022 World Health Organization Classification of the tumors of the urinary system and male genital organs part A: Renal, penile and testicular tumors. Eur. Urol. 2022, 82, 458.

- Moch, H.; Cubilla, A.L.; Humphrey, P.; Reuter, V.E.; Ulbright, T.M. The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary and male genital organs, part A: Renal, penile and testicular tumours. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 93–105.

- Talerman, A. Spermatocytic seminoma: Clinicopathological study of 22 cases. Cancer 1980, 45, 2169–2176.

- Burke, A.; Mostofi, F.K. Spermatocytic seminoma, a clinicopathologic study of 79 cases. J. Urol. Pathol. 1993, 1, 21–32.

- Rabade, K.; Panjwani, P.K.; Menon, S.; Prakash, G.; Pal, M.; Bakshi, G.; Desai, S. Spermatocytic tumor of testis: A case series of 26 cases elucidating unusual patterns with diagnostic and treatment dilemmas. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2022, 18, S449–S454.

- Carrière, P.; Baade, P.; Fritschi, L. Population based incidence and age distribution of spermatocytic seminoma. J. Urol. 2007, 178, 125–128.

- Secondino, S.; Rosti, G.; Tralongo, A.C.; Nolè, F.; Alaimo, D.; Carminati, O.; Naspro, R.L.J.; Pedrazzoli, P. Testicular tumors in the “elderly” population. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 972151.

- Hu, R.; Ulbright, T.M.; Young, R.H. Spermatocytic seminoma: A report of 85 cases emphasizing its morphologic spectrum including some aspects not widely known. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2019, 43, 1–11.

- Patel, P.M.; Patel, H.D.; Koehne, E.L.; Doshi, C.; Belshoff, A.; Seffren, C.M.; Baker, M.; Gorbonos, A.; Gupta, G. Contemporary trends in presentation and management of spermatocytic seminoma. Urology 2020, 146, 177–182.

- Masson, P. A study of seminomas. Rev. Can. Biol. 1946, 5, 361–387.

- Rosenberg, C.; Mostert, M.C.; Schut, T.B.; van de Pol, M.; van Echten, J.; de Jong, B.; Raap, A.K.; Tanke, H.; Oosterhuis, J.W.; Looijenga, L.H. Chromosomal constitution of human spermatocytic seminomas: Comparative genomic hybridization supported by conventional and interphase cytogenetics. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1998, 23, 286–291.

- Freitag, C.E.; Sukov, W.R.; Bryce, A.H.; Berg, J.V.; Vanderbilt, C.M.; Shen, W.; Smadbeck, J.B.; Greipp, P.T.; Ketterling, R.P.; Jenkins, R.B.; et al. Assessment of isochromosome 12p and 12q abnormalities in germ cell tumors using fluorescence in situ hybridization, single-nucleotide polymorphism array, and next-generation sequencing-mate-pair sequencing. Hum. Pathol. 2021, 112, 20–24.

- Looijenga, L.H.; Hersmus, R.; Gillis, A.J.M.; Pfundt, R.; Stoop, H.J.; van Gurp, R.J.H.L.M.; Veltman, J.; Baverloo, H.B.; van Drunen, E.; van Kessel, A.G.; et al. Genomic and expression profiling of human spermatocytic seminomas: Primary spermatocyte as tumorigenic precursor and DMRT1 as candidate chromosome 9 gene. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 290–302.

- Dundr, P.; Pesl, M.; Povýsil, C.; Prokopová, P.; Pavlík, I.; Soukup, V.; Dvoracek, J. Anaplastic variant of spermatocytic seminoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2007, 203, 621–624.

- Chennoufi, M.; Boukhannous, I.; Mokhtari, M.; El Moudane, A.; Barki, A. Spermatocytic seminoma of testis associated with undifferentiated sarcoma revealed in metastatic disease: A review and case report analysis. Urol. Case Rep. 2021, 38, 101732.

- Ulbright, T.M.; Young, R.H. Seminoma with tubular, microcystic, and related patterns: A study of 28 cases of unusual morphologic variants that often cause confusion with yolk sac tumor. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2005, 29, 500–505.

- Kao, C.S.; Ulbright, T.M.; Young, R.H.; Idrees, M.T. Testicular embryonal carcinoma: A morphologic study of 180 cases highlighting unusual and unemphasized aspects. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014, 38, 689–697.

- Ferry, J.A.; Harris, N.L.; Young, R.H.; Coen, J.; Zietman, A.; Scully, R.E. Malignant lymphoma of the testis, epididymis, and spermatic cord. A clinicopathologic study of 69 cases with immunophenotypic analysis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1994, 18, 376–390.

- Cheah, C.Y.; Wirth, A.; Seymours, J.F. Primary testicular lymphoma. Blood 2014, 123, 486–492.

- Al-Obaidy, K.; Idrees, M. Testicular tumors: A contemporary update on morphologic, immunohistochemical and molecular features. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2021, 28, 258–275.

- Narins, H.; Chevli, K.; Gilbert, R.; Duff, M.; Toenniessen, A.; Hu, Y. Bilateral spermatocytic seminoma: A case report. Res. Rep. Urol. 2014, 6, 63–65.

- Bergner, D.M.; Duck, G.B.; Rao, M. Bilateral sequential spermatocytic seminoma. J. Urol. 1980, 124, 565.

- Aggarwal, N.; Parwani, A.V. Spermatocytic seminoma. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2009, 133, 1985–1988.

- Stevens, M.J.; Gildersleve, J.; Jameson, C.F.; Horwich, A. Spermatocytic seminoma in a maldescended testis. Br. J. Urol. 1993, 72, 657–659.

- Swerdlow, A.J.; Higgins, C.D.; Pike, M.C. Risk of testicular cancer in cohort of boys with cryptorchidism. BMJ 1997, 314, 1507–1511.

- Grogg, J.B.; Schneider, K.; Bode, P.K.; Wettstein, M.S.; Kranzbuhler, B.; Eberli, D.; Sulser, T.; Beyer, J.; Hermanns, T.; Fankhauser, C.D. A systematic review of treatment outcomes in localized and metastatic spermatocytic tumors of the testis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 3037–3045.

- Pedrazzoli, P.; Rosti, G.; Soresini, E.; Ciani, S.; Secondino, S. Serum tumour markers in germ cell tumours: From diagnosis to cure. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 159, 103224.

- Gru, A.A.; Williams, E.S.; Cao, D. Mixed gonadal germ cell tumor composed of a spermatocytic tumor-like component and germinoma arising in gonadoblastoma in a phenotypic woman with a 46, XX peripheral karyotype: Report of the first case. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2017, 41, 1290–1297.

- Patrikidou, A.; Cazzaniga, W.; Berney, D.; Boormans, J.; de Angst, I.; Di Nardo, D.; Fankhauser, C.; Fischer, S.; Gravina, C.; Gremmels, H.; et al. Europenan association of urology guidelines on testicular cancer: 2023 update. Eur. Urol. 2023. S0302-2838(23)02732-X.

- Chung, P.; Daugaard, G.; Tyldesley, S.; Atenafu, E.G.; Panzarella, T.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Warde, P. Evaluation of a prognostic model for risk of relapse in stage I seminoma surveillance. Cancer Med. 2015, 4, 155–160.

- Jeong, Y.; Cheon, J.; Kim, T.O. Conventional cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy is effective in the treatment of metastatic spermatocytic seminoma with extensive rhabdomyosarcomatous transformation. Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 47, 931–936.

- Fankhauser, C.D.; Grogg, J.B.; Rothermundt, C.; Clarke, N.W. Treatment and follow up of rare testis tumors. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 148, 667–671.