Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Stephen Emencheta.

Due to the increasing limitations and negative impacts of the current options for preventing and managing diseases, including chemotherapeutic drugs and radiation, alternative therapies are needed, especially ones utilizing and maximizing natural products (NPs). NPs abound with diverse bioactive primary and secondary metabolites and compounds with therapeutic properties.

- marine probiotics

- Pseudoalteromonas spp.

- therapeutic effects

1. Introduction

Natural products (NPs) are highly structurally diversified, ubiquitous life forms and derivatives of living organisms and minerals. They have been used extensively, especially in traditional medicine, to manage diverse diseases [1]. They have also contributed immensely to drug discovery in making current conventional drugs, serving as a direct source of medicinal substances, raw materials in drug production, lead compound design prototypes, and taxonomic biomarkers for new drug search and discovery [2]. NPs are associated with prominent, apparent beneficial properties [3] (as shown in Table 1) against conventional drugs or radiotherapy (as implicated in cancer management), including minimal side effects, toxicity, allergenicity, and low-cost isolation, identification, characterization, and production.

Synthetic drugs, including antibiotics used in aquaculture, primarily aim to prevent infection, leading to fatalities of “aquatic products” with correspondingly low productivity. However, their irrational use undermines the purpose. Although used optimally, it does not guarantee a clean bill of zero health risks to humans [4]. These drugs, including chloramphenicol, sulfamethazine, oxytetracycline, and furazolidone, remain residues in aquatic animals, with their bioaccumulation and biomagnification linked to human carcinogenicity [5,6,7][5][6][7]. Cancer is a leading cause of death globally, with yearly increasing cases [8] and an estimated 19 and 10 million new occurrences and deaths, respectively, in 2020 [9]. The risk/predisposing factors impact the DNA repair system following mutation in a single cell [10]. The pioneer single precancer cell produces many neoplastic cells and tissues via specific mechanisms, leading to undesirable physiological states of the cell, the surrounding cells, tissues, and the entire system. Clinically managing or controlling cancer cells often involves using single and multiple chemotherapeutic drugs to kill or destroy benign or malignant tumor cells and applying radiation to target sites [11,12][11][12]. Chemotherapy usually consists of administering high doses of synthetic chemicals for extended durations. Thus, the chemotherapeutic management of cancer has obvious negative implications. Most notable are the drop in the quality/standard of living of most recipient patients due to the extensive side effects of chemotherapeutic drugs on the surrounding cells and systems, the cost of acquiring and maintaining the therapy, and the contribution of chemicals to increasing drug resistance [10]. Radiation therapy has negative implications, including bioaccumulation of radiation, inadequate replacement of damaged stem cells, and injury [13].

NPs are also being exploited to produce anti-infective agents, especially with emerging infectious diseases, antibiotic resistance, and the dearth of new chemotherapeutic agents. Furthermore, the importance of NPs with immunomodulatory and antioxidant properties in combating bioterrorism cannot be overemphasized. The inadequacies in current therapeutic options highlight the need for safer, cheaper, and cost-effective alternative therapies, mainly from various natural products (NPs) that are abundant in the environment. One awakening mindset involves using marine probiotics for their inherent enormous potential [3]. Marine probiotics are a group of natural microbial dwellers of the marine ecosystem that, through their biological activities, apparently contribute to improving aquatic life forms through disease resistance, growth, stress tolerance, reproduction, and water quality [14,15][14][15]. They are being exploited for possible utilization in disease prevention and management and have many genera and species belonging to different phyla, including Pseudoalteromonas spp. The cold-adapted Pseudoalteromonas spp. are diverse understudied marine probiotics usually resident in the extreme marine environment and has shown great potential for therapeutic and biotechnological applications [16].

Table 1. Comparison of side effects of chemotherapeutic drugs, radiation (as applied in cancer management), and natural products.

| S/N | Therapy | Side Effects | Therapy Cost | Production Cost | Drug Resistance | Bioaccumulation | Mutation | Injury | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chemotherapeutic drugs | Extensive side effects | High cost of acquiring and maintaining therapy | High cost of development and production of candidate drugs | Contribution of chemicals to increasing drug resistance | Bioaccumulation of chemicals | Not applicable | Not applicable | [19][17] |

| 2 | Radiation | Extensive side effects | High cost of acquiring and maintaining therapy | Not applicable | Not Applicable | Bioaccumulation of radiation | Induction of mutation | Inadequate replacement of damaged stem cells | [13] |

| 3 | Natural products | Minimal side effects | Relatively low cost of acquiring and maintaining therapy | Relatively low cost of isolation, identification, characterization, and production | Little or no contribution to resistance | Little or no accumulation | No induction of mutation | No injuries | [20][18] |

2. Probiotics, Sources, and Classifications

Probiotics resulting from the Greek words “Pro bios,” which translates to “for life” [21][19], are a class of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses (such as bacteriophages), and fungi (yeast and mold) that can be ingested or topically applied for dietary and numerous medicinal (physiological and immunological) purposes [8,22,23][8][20][21]. Examples include Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus, Bacillus, Escherichia coli, Lactobacillus, Saccharomyces, Coccobacilli, and Propionibacterium and are in varying classifications, mechanisms of action, and corresponding functions. They preserve specific qualities, including, but not limited to, the ability to inhibit pathogens in the gut, navigate and survive via intestinal transit and gastric/bile secretions, adhere to the mucosa of the intestine, have immunomodulating and other biological effects [10,24][10][22]. Probiotic strains should be thoroughly characterized, safe for the intended application, backed by at least one successful human clinical trial per generally accepted scientific criteria, and alive in adequate numbers in the product at the time of usage [25][23]. Other considerations in choosing for medicinal purposes include non-toxicity, non-pathogenicity, beneficial effects, and appreciable shelf life. Probiotics have been applied in managing diverse medical conditions [10]. Also, several preclinical and clinical trials have suggested potent therapeutic applications. Probiotics are traditionally used and present in fermented food products (e.g., milk, yogurt, cheese, buttermilk, kombucha, sauerkraut, and tempeh) and supplements [10]. The major classifications of probiotics include lactic acid (e.g., Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, and Bifidobacterium) and non-lactic acid strains (e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium, and Propionibacterium), yeasts (e.g., Saccharomyces, Candida, and Debaryomyces) and viruses, with each group exhibiting different mode of operation [26][24]. Based on ecosystems, terrestrial and aquatic or marine-based probiotics are the classifications [27][25]. Probiotics are involved in the production of inhibitory substances which prevent the adhesion of pathogens to the intestinal epithelium, direct inhibition of gram-negative bacteria, regulation of short-chain fatty acids, downregulation of proinflammatory cytokines, colonization of intestinal permeability, regulation of electrolyte adsorption, maintenance of the immune response of the intestine, and maintenance of lipid metabolism [26][24].3. Marine Probiotics and General Therapeutic Potentials

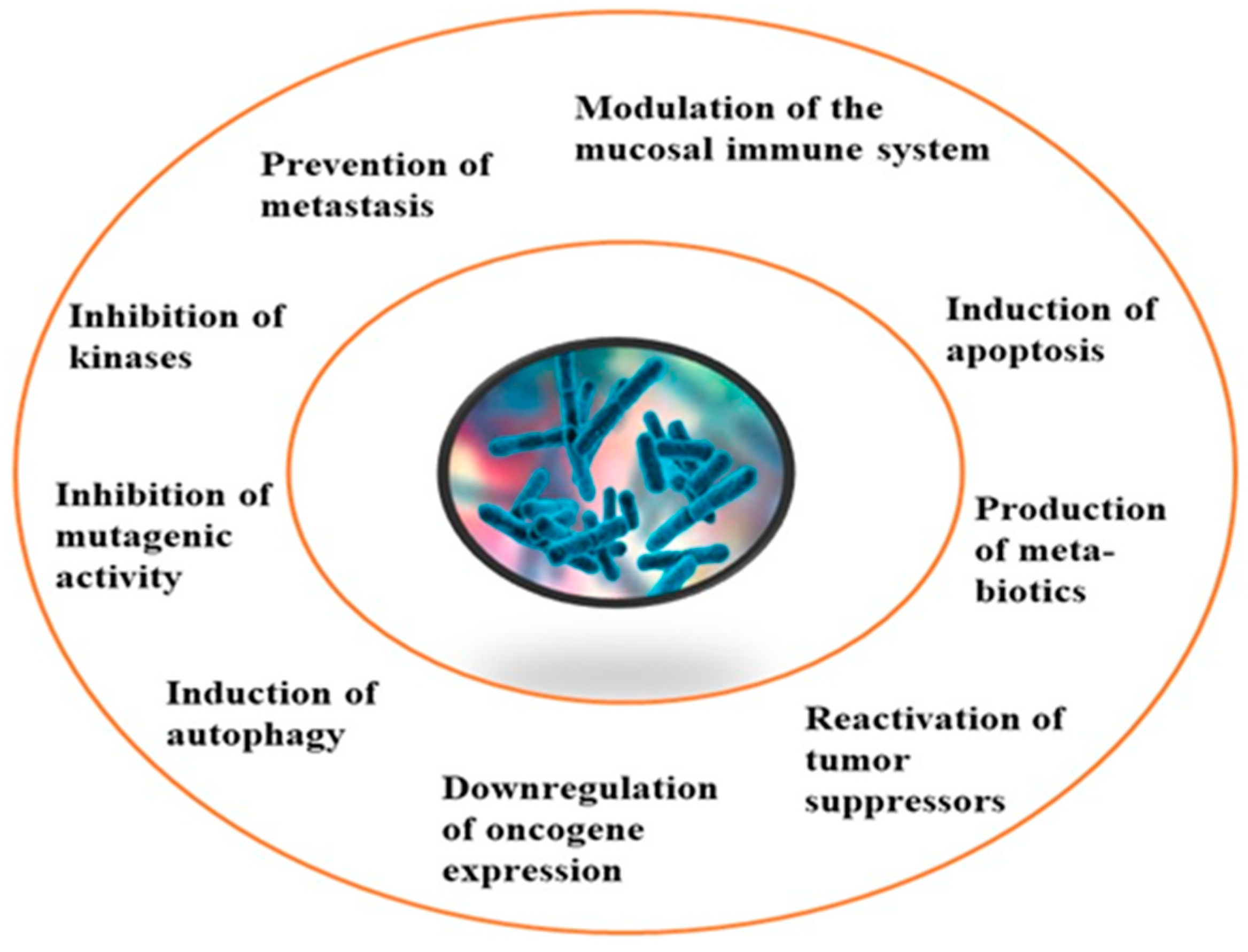

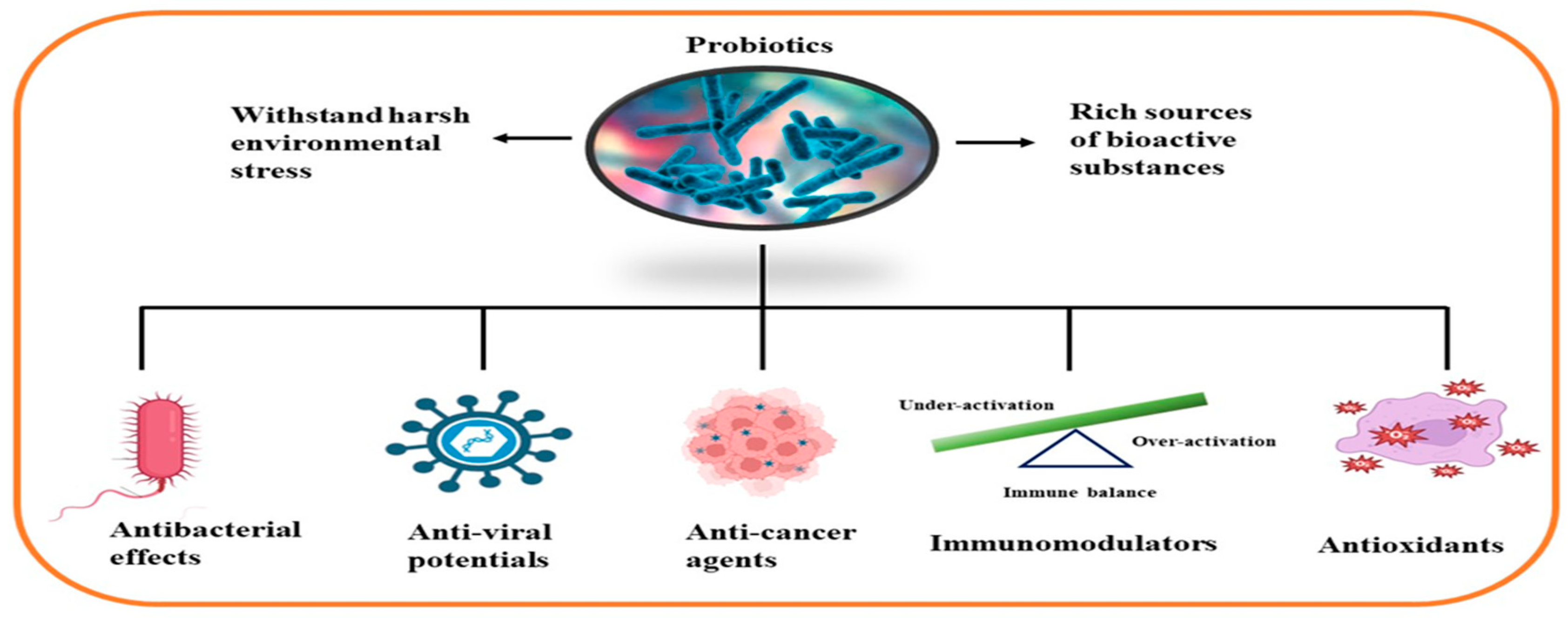

Marine probiotics abound in the aquatic ecosystems. Indigenous and exogenous microbiota from aquatic animals is the primary source for isolating probiotic strains, with the Lactobacilli, Pseudomonas, Shewanella, Fluorescens, Phaeobacter, and Bifidobacteria being the most common genera [28,29][26][27]. They have many beneficial roles, including the protection of aquatic life forms. They naturally act as disease control agents in aquatic plants and fishes, promote growth, improve digestion and immune systems, provide sources of nutrients, improve water quality, encourage reproduction, form beneficial relationships with the host and the environment, enhance gut health and immune response in higher animals, and improve human health by preventing and treating various diseases such as cancer, gastrointestinal disorders, respiratory infections, and skin diseases [21,30,31][19][28][29]. They also engage in the blockage of the pathogen’s ability to utilize certain nutrients, prevention of their attachment to the host environment, distortion of the enzymatic activities of the pathogens, enhancement of the quality of water, stimulation of the immune system, and improvement of host nutrition. Marine probiotics are a promising source of novel bioactive compounds with anticancer, antibacterial, immunomodulatory, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral properties, as have been implicated in several studies [27,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39][25][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37]. Studies have detailed the potential of yeast as a probiotic for cancer management [40][38], especially the isolates from marine ecosystems [41,42,43,44,45][39][40][41][42][43] and floras of the gut system [42][40]. Various marine yeast microbiota genera with potential anticancer effects have been identified, including Saccharomyces, the most studied genera, particularly in colorectal cancer, as discussed by Sambrani et al. [40][38]. Others are Candida, Debaryomyces, Kluyveromyces, Pichia, Saccharomyces, Cryptococcus, Rhodosporidium, Rhodotorula, Sporobolomyces, Mrakiafrigida, Guehomyces pullulans, Rhodotorula, Rhodosporidium, Yarrowialipolytica, Aureobasidium, Metschnikowia spp., Torulopsis spp., Pichia, Kluyveromyces, Williopsis, Pseudozyma spp., Hansenula, Trichosporon, Filobasidium, Leucosporidium, Mrakiafrigida, Guehomyces pullulans, Metschnikowia, Rhodotorula, Cystobasidium, and Yamadazyma [45,46][43][44]. The lactic acid bacteria (LAB) genera and species, including Lactobacillus (L. casei, L. acidophilus, L. fermentum, L. delbrueckii, L. helveticus, L. paracasei, L. pentosus, L. plantarum, L. salivarius, L. rhamnosus GG, L. johnsonii), Bifidobacterium (B. bifidum, B. longum, B. lactis, B. infantis, B. breve, B. adolescentis), Leuconostoc spp. (Ln. lactis, Ln. mesenteroidessubsp. Cremoris, Ln. mesenteroides subsp. dextranicum), and Streptococcus spp. (S. salivarius subsp. thermophilus) are highly diversified and studied probiotic bacteria implicated in the inhibition and apoptosis of various human cancer cells [32,47,48,49][30][45][46][47]. Other reported bacterial probionts include Bacillus (B. fermenticus, B. subtilis), Clostridium butyricum, Enterococcus faecium, Pediococcus pentosaceus, Lactococcus lactis, Propionibacterium, and Streptococcus thermophilus [49][47]. Actinomycetes such as Streptomyces and Micromonosporaceae are also promising candidates. Trioxacarcins A–C, anthraquinone, Macrodiolide tartrolon D, and Streptokordin obtained from Streptomyces spp. exhibited significant antitumor/cytotoxic activities against various cancer cell lines [50,51,52][48][49][50]. Although limited information is available on cancer management among marine probiotics, few probiotics are known to possess anticancer properties through several mechanisms (Figure 1), primarily due to meta-biotics, which consist of structural components, metabolites, and signaling molecules with specific chemical structures as shown in Enterococcus lactis IW5 [53,54,55][51][52][53]. These components optimize various physiological functions of the host, including regulatory, metabolic, and behavioral reactions. Marine probiotics, such as Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria, modify the mucosa by increasing the production of chemokines and host defense peptides, inducing dendritic cell maturation, and increasing cell proliferation and apoptosis [51][49]. Marine probiotics can modulate cancer by inducing apoptosis, inhibiting mutagenic activity, downregulating oncogene expression, inducing autophagy, inhibiting kinases, reactivating tumor suppressors, preventing metastasis, and producing meta-biotics, as already shown in B. animalis, B. infantis, B. bifidum, L. paracasei, L. acidophilus, and L. plantarum I-UL4 against MFC7 cancer cells [53,54][51][52]. Although probiotics alone may not suffice in treating cancer, they can mitigate colorectal cancer (CRC) by enhancing the efficacy of treatments and acting on the immune system [56][54]. Studies have shown that probiotic strains, specifically lactic acid bacteria mixtures, can differentially induce and modulate macrophage pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and phagocytosis [53][51]. It also can mitigate the effects of DMH-induced colon shortening and positively affect leukocyte count and colon tumor growth [56][54]. The combinations also induce the excretion of proinflammatory IL-18 by tumor cells and are crucial in mitigating CRC [56][54]. Probiotics generally exhibit antitumor activities by enhancing the intestinal microbiota, degrading possible carcinogens, and modulating gut-associated and systemic immune responses [57][55]. Worthy of mention is that several anticancer drugs of marine origin are in clinical use with sufficient approvals, including cytarabine, vidarabine, nelarabine, fludarabine phosphate, trabectedin, eribulin mesylate, brentuximab vedotin, polatuzumabvedotin, enfortumabvedotin, belantamabmafodotin, plitidepsin, lurbinectedin, bryostatins, discodermolide, eleutherobin, and sarcodictyin [41,58][39][56].

Figure 1. General mechanism of action of cancer prevention and management.

Table 2. Representative marine probiotic-derived drugs and their microbial sources.

| Bioactivity | Drugs | Microbial Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anticancer | Actinomycin, Salinosporamide A (Marizomib®) (NPI-0052), Plinabulin, Enzastaurin, Lestaurtinib, Becatecarin, GSK2857916, Ladiratuzumab vedotin, Tisotumab vedotin, Glembatumumab vedotin, Denintuzumab mafodotin, Midostaurin (Rydapt®), Pinatuzumab vedotin, ASG-15ME, Lifastuzumab vedotin, Vandortuzumab vedotin, UCN-01 | Streptomyces sp., Salinospora tropica, Aspergillus sp., Streptomyces staurosporeus, Saccharothrix aerocolonigenes, Caldora penicillata | [75,76][73][74] |

| Antimicrobial | Gageotetrins A–C, Gageopeptides A–D, Ieodoglucomide 1, 2, Marinopyrrole A, Merochlorin A, Anthracimycin | Bacillus subtillis 109GGC020, Bacillus licheniformis 09IDYM23, Streptomyces sp. | [77,78][75][76] |

| Immunomodulatory | Brentuximab vedotin, Polatuzumab vedotin (DCDS-4501A), Belantamab madofotin-blmf | Symploca sp. VP642, Cyanobacteria | [79][77] |

| Antioxidant | Hexaricins F, Asperchalasine I | Streptosporangium sp. CGMCC 4.7309, Mycosphaerella sp. SYSU-DZG0 | [80][78] |

| Antiinflammatory | Cyclic peptide cyclomarin, Violaceomide A, Dehydrocurvularin | Streptomyces sp., Aspergillus terreus H010, Penicillium sumatrense | [78,80][76][78] |

Figure 2. Therapeutic potentials of marine probiotics.

References

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Supuran, C.T. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216.

- Calixto, J.B. The role of natural products in modern drug discovery. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2019, 91 (Suppl. S3), e20190105.

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803.

- Code of Practice for Fish and Fishery Products. FAO and WHO; 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cb0658en (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Chen, Z.; Guo, J.; Jiang, Y.; Shao, Y. High concentration and high dose of disinfectants and antibiotics used during the COVID-19 pandemic threaten human health. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 11.

- Okocha, R.C.; Olatoye, I.O.; Adedeji, O.B. Food safety impacts of antimicrobial use and their residues in aquaculture. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 21.

- The Rules Governing Medicinal Products in the European Union. In GMP/ISO Quality Audit Manual for Healthcare Manufacturers and Their Suppliers, (Volume 2—Regulations, Standards, and Guidelines), 6th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 257–316. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9780203026656/chapters/10.3109/9780203026656-14 (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Tripathy, A.; Dash, J.; Kancharla, S.; Kolli, P.; Mahajan, D.; Senapati, S.; Jena, M.K. Probiotics: A promising candidate for management of colorectal cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 3178.

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249.

- Bedada, T.L.; Feto, T.K.; Awoke, K.S.; Garedew, A.D.; Yifat, F.T.; Birri, D.J. Probiotics for cancer alternative prevention and treatment. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110409.

- Janelsins, M.C.; Kesler, S.R.; Ahles, T.A.; Morrow, G.R. Prevalence, mechanisms, and management of cancer-related cognitive impairment. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2014, 26, 102–113.

- Sultana, A.; Smith, C.T.; Cunningham, D.; Starling, N.; Neoptolemos, J.P.; Ghaneh, P. Meta-analyses of chemotherapy for locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 2607–2615.

- Majeed, H.; Gupta, V. Adverse Effects of Radiation Therapy. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563259/ (accessed on 4 March 2023).

- Tarnecki, A.M.; Wafapoor, M.; Phillips, R.N.; Rhody, N.R. Benefits of a Bacillus probiotic to larval fish survival and transport stress resistance. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4892.

- Martínez, C.P.; Ibáñez, A.L.; Monroy, H.O.A.; Ramírez, S.H.C. Use of probiotics in aquaculture. ISRN Microbiol. 2012, 2012, 916845.

- Borchert, E.; Knobloch, S.; Dwyer, E.; Flynn, S.; Jackson, S.A.; Jóhannsson, R.; Marteinsson, V.T.; O’Gara, F.; Dobson, A.D.W. Biotechnological Potential of Cold Adapted Pseudoalteromonas spp. Isolated from ‘Deep Sea’ Sponges. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5484134/ (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Leighl, N.B.; Nirmalakumar, S.; Ezeife, D.A.; Gyawali, B. An arm and a leg: The rising cost of cancer drugs and impact on access. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book. 2021, 41, e1–e12.

- Dzobo, K. The role of natural products as sources of therapeutic agents for innovative drug discovery. Compr. Pharmacol. 2022, 408–422.

- Sayes, C.; Leyton, Y.; Riquelme, C. Probiotic bacteria as an healthy alternative for fish aquaculture. Antibiot. Use Anim. Savic. Ed. Rij. Croat. InTech. Publ. 2018, 115–132.

- Blackall, L.L.; Dungan, A.M.; Hartman, L.M.; van Oppen, M.J. Probiotics for corals. Microbiol. Aust. 2020, 41, 100–104.

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Swelum, A.A.; Abo Ghanima, M.M.; Shukry, M.; Omar, A.A.; Taha, A.E.; Salem, H.M.; El-Tahan, A.M.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; El-Hack, E.A. Shrimp production, the most important diseases that threaten it, and the role of probiotics in confronting these diseases: A review. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 144, 126–140.

- Saraf, K.; Shashikanth, M.C.; Priy, T.; Chaitanya, N.C. Probiotics-do they have a role in medicine and dentistry. J. Assoc. Physicia. Ind. 2010, 58, 488–490.

- Binda, S.; Hill, C.; Johansen, E.; Obis, D.; Pot, B.; Sanders, M.E.; Tremblay, A.; Ouwehand, A.C. Criteria to qualify mas “Probiotic” in foods and dietary supplements. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1662.

- Sen, M. Role of probiotics in health and disease—A review. Int. J. Adv. Life. Sci. Res. 2019, 30, 1–11.

- Mujeeb, I.; Ali, S.H.; Qambarani, M.; Ali, S.A. Marine bacteria as potential probiotics in aquaculture. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2022, e5631.

- Vázquez, J.A.; Durán, A.; Nogueira, M.; Menduíña, A.; Antunes, J.; Freitas, A.C.; Gomes, A.M. Production of marine probiotic bacteria in a cost-effective marine media based on peptones obtained from discarded fish by-products. Microorganism 2020, 8, 1121.

- Kim, S.K.; Bhatnagar, I.; Kang, K.H. Development of marine probiotics: Prospects and approach. Adv. Food. Nutr. Res. 2012, 65, 353–362.

- Madison, D.; Schubiger, C.; Lunda, S.; Mueller, R.S.; Langdon, C. A marine probiotic treatment against the bacterial pathogen Vibrio coralliilyticus to improve the performance of Pacific (Crassostrea gigas) and Kumamoto (C. sikamea) oyster larvae. Aquaculture 2022, 560, 738611.

- Sumithra, T.G.; Reshma, K.J.; Christo, J.P.; Anusree, V.N.; Drisya, D.; Kishor, T.G.; Revathi, D.N.; Sanil, N.K. A glimpse towards cultivable hemolymph microbiota of marine crabs: Untapped resource for aquatic probiotics/antibacterial agents. Aquaculture 2019, 501, 119–127.

- Anas, K.K.; Mathew, S. Marine Nutraceuticals; ICAR-Central Institute of Fisheries Technology: Willingdon Island, Kochi, Kerala, India, 2018.

- Makled, S.O.; Hamdan, A.M.; El-Sayed, A.F.M. Growth promotion and immune stimulation in Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, fingerlings following dietary administration of a novel marine probiotic, Psychrobacter maritimus S. Probiot. Antimicrob. Proteins 2020, 12, 365–374.

- Koga, A.; Goto, M.; Hayashi, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Miyasaka, H. Probiotic effects of a marine purple non-sulfur bacterium, Rhodovulum sulfidophilum KKMI01, on Kuruma Shrimp (Marsupenaeus japonicus). Microorganisms 2022, 10, 244.

- Norouzi, H.; Danesh, A.; Mohseni, M.; Rabbani, K.M. Marine actinomycetes with probiotic potential and bioactivity against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Int. J. Mol. Cell. Med. 2018, 7, 44–52.

- Reyes-Becerril, M.; Alamillo, E.; Angulo, C. Probiotic and immunomodulatory activity of marine yeast Yarrowia lipolytica strains and response against Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Fish. Probiot. Antimicrob. Proteins 2021, 13, 1292–1305.

- Hamdan, A.M.; El-Sayed, A.F.M.; Mahmoud, M.M. Effects of a novel marine probiotic, Lactobacillus plantarum AH 78, on growth performance and immune response of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 120, 1061–1073.

- Gutiérrez, F.A.; Padilla, D.; Real, F.; Ramos, S.M.J.; Acosta-Hernández, B.; Sánchez, H.A.; García-Álvarez, N.; Rosario Medina, I.; Silva Sergent, F.; Déniz, S.; et al. Screening of new potential probiotics strains against Photobacterium damselae Subsp. piscicida for marine aquaculture. Animals 2021, 11, 2029.

- Victor, O.E. A Review on the Application and Benefits of Probiotics Supplements in Fish Culture. Oceanogr. Fish Open Access J. 2020, 11. Available online: https://juniperpublishers.com/ofoaj/OFOAJ.MS.ID.555817.php (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Sambrani, R.; Abdolalizadeh, J.; Kohan, L.; Jafari, B. Recent advances in the application of probiotic yeasts, particularly Saccharomyces, as an adjuvant therapy in the management of cancer with focus on colorectal cancer. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 951–960.

- Barreca, M.; Spanò, V.; Montalbano, A.; Cueto, M.; Díaz Marrero, A.R.; Deniz, I.; Erdoğan, A.; Lukić Bilela, L.; Moulin, C.; Taffin-de-Givenchy, E.; et al. Marine anticancer agents: An overview with a particular focus on their chemical classes. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 619.

- El-Baz, A.F.; El-Enshasy, H.A.; Shetaia, Y.M.; Mahrous, H.; Othman, N.Z.; Yousef, A.E. Semi-industrial scale production of a new yeast with probiotic traits, Cryptococcus sp. YMHS, isolated from the red sea. Probiot. Antimicrob. Prot. 2018, 10, 77–88.

- Reyes-Becerril, M.; Ângulo, C.; Ângulo, M.; Esteban, M.Á. Probiotic properties of Debaryomyces hansenii BCS004 and their immunostimulatory effect in supplemented diets for gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata). Aquac. Res. 2021, 52, 2715–2726.

- Tseng, C.C.; Lin, Y.J.; Liu, W.; Lin, H.Y.; Chou, H.Y.; Thia, C.; Wu, J.H.; Chang, J.S.; Wen, Z.H.; Chang, J.J.; et al. Metabolic engineering probiotic yeast produces 3S, 3′S-astaxanthin to inhibit B16F10 metastasis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 135, 110993.

- Valderrama, B.; Ruiz, J.J.; Gutiérrez, M.S.; Alveal, K.; Caruffo, M.; Oliva, M.; Flores, H.; Silva, A.; Toro, M.; Reyes-Jara, A.; et al. Cultivable yeast microbiota from the marine fish species Genypterus chilensis and Seriolella violacea. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 515.

- Tian, B.C.; Liu, G.L.; Chi, Z.; Hu, Z.; Chi, Z.M. Occurrence and distribution of strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in China Seas. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 590.

- Wasana, W.P.; Senevirathne, A.; Nikapitiya, C.; Eom, T.Y.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.S.; Kang, D.H.; Oh, C.; De Zoysa, M. A novel Pseudoalteromonas xiamenensis marine isolate as a potential probiotic: Anti-inflammatory and innate immune modulatory effects against thermal and pathogenic stresses. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 707.

- Vidya, S.; Thiruneelakandan, G. Probiotic potentials of lactobacillus and its anti cancer activity. Int. J. Curr. Res. 2015, 7, 20680–20684.

- Śliżewska, K.; Markowiak-Kopeć, P.; Śliżewska, W. The role of probiotics in cancer prevention. Cancers 2020, 13, 20.

- Dongare, P.N.; Motule, A.S.; More, M.P.; Patinge, P.A.; Bakal, R. An overview on anti-cancer drugs from marine source. World J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 10, 950–956.

- Singh, A.; Krishna, S. Immunomodulatory and Therapeutic Potential of Marine Flora Products in the Treatment of Cancer. In Bioactive Natural Products for the Management of Cancer: From Bench to Bedside; Sharma, A.K., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 139–166. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-13-7607-8_7 (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Dharmaraj, S. Marine Streptomyces as a novel source of bioactive substances. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 26, 2123–2139.

- Malik, S.S.; Saeed, A.; Baig, M.; Asif, N.; Masood, N.; Yasmin, A. Anticarcinogenecity of microbiota and probiotics in breast cancer. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21, 655–666.

- Sankarapandian, V.; Venmathi Maran, B.A.; Rajendran, R.L.; Jogalekar, M.P.; Gurunagarajan, S.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Gangadaran, P.; Ahn, B.C. An update on the effectiveness of probiotics in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Life 2022, 12, 59.

- Shenderov, B.A. Metabiotics: Novel idea or natural development of probiotic conception. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2013, 12, 24.

- Hradicka, P.; Beal, J.; Kassayova, M.; Foey, A.; Demeckova, V. A novel lactic acid bacteria mixture: Macrophage-targeted prophylactic intervention in colorectal cancer management. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 387.

- Yu, A.Q.; Li, L. The potential role of probiotics in cancer prevention and treatment. Nutr. Cancer 2016, 68, 535–544.

- Sithranga Boopathy, N.; Kathiresan, K. Anticancer drugs from marine flora: An overview. J. Oncol. 2010, 2010, 214186.

- Pereira, W.A.; Piazentin, A.C.M.; de Oliveira, R.C.; Mendonça, C.M.N.; Tabata, Y.A.; Mendes, M.A.; Fock, R.A.; Makiyama, E.N.; Corrêa, B.; Vallejo, M.; et al. Bacteriocinogenic probiotic bacteria isolated from an aquatic environment inhibit the growth of food and fish pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5530.

- Sarika, A.; Lipton, A.; Aishwarya, M.; Mol, R.R. Lactic Acid Bacteria from Marine Fish: Antimicrobial Resistance and Production of Bacteriocin Effective against L. monocytogenes In Situ. J. Food Microbiol. Saf. Hyg. 2018, 3. Available online: https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/lactic-acid-bacteria-from-marine-fish-antimicrobial-resistance-and-production-of-bacteriocin-effective-against-l-monocytogenes-in-2476-2059-1000128-96294.html (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Chbel, A.; Rodriguez-Castro, J.; Quinteiro, J.; Rey-Méndez, M.; Delgado, A.S.; Soukri, A.; Khalfi, B.E. Isolation, Molecular Identification and Antibacterial Potential of Marine Bacteria from Deep Atlantic Ocean of Morocco. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 2022. Available online: https://publish.kne-publishing.com/index.php/AJMB/article/view/9827 (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Alonso, S.; Carmen Castro, M.; Berdasco, M.; de la Banda, I.G.; Moreno-Ventas, X.; de Rojas, A.H. Isolation and partial characterization of lactic acid bacteria from the gut microbiota of marine fishes for potential application as probiotics in aquaculture. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2019, 11, 569–579.

- Kaktcham, P.M.; Temgoua, J.B.; Ngoufack Zambou, F.; Diaz-Ruiz, G.; Wacher, C.; Pérez-Chabela, M.d.L. Quantitative analyses of the bacterial microbiota of rearing environment, tilapia and common carp cultured in earthen ponds and inhibitory activity of its lactic acid bacteria on fish spoilage and pathogenic bacteria. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 33, 32.

- Sironi, M.; Cagliani, R.; Forni, D.; Clerici, M. Evolutionary insights into host–pathogen interactions from mammalian sequence data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 224–236.

- Harikrishnan, R.; Balasundaram, C.; Heo, M.S. Effect of probiotics enriched diet on Paralichthys olivaceus infected with lymphocystis disease virus (LCDV). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010, 29, 868–874.

- Liu, C.H.; Chiu, C.H.; Wang, S.W.; Cheng, W. Dietary administration of the probiotic, Bacillus subtilis E20, enhances the growth, innate immune responses, and disease resistance of the grouper, Epinephelus coioides. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2012, 33, 699–706.

- Balcázar, J.L.; Vendrell, D.; de Blas, I.; Ruiz-Zarzuela, I.; Gironés, O.; Múzquiz, J.L. In vitro competitive adhesion and production of antagonistic compounds by lactic acid bacteria against fish pathogens. Vet. Microbiol. 2007, 122, 373–380.

- Chattaraj, S.; Ganguly, A.; Mandal, A.; Das Mohapatra, P.K. A review of the role of probiotics for the control of viral diseases in aquaculture. Aquac. Int. 2022, 30, 2513–2539.

- Sundararaman, A.; Ray, M.; Ravindra, P.V.; Halami, P.M. Role of probiotics to combat viral infections with emphasis on COVID-19. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 8089–8104.

- Zaharuddin, L.; Mokhtar, N.M.; Muhammad, N.K.N.; Raja, A.R.A. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of probiotics in post-surgical colorectal cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019, 19, 131.

- Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A.; Chandra, N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 118.

- Lidon, F.; Silva, M. An overview on applications and side effects of antioxidant food additives. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2016, 28, 823.

- Husain, F.; Duraisamy, S.; Balakrishnan, S.; Ranjith, S.; Chidambaram, P.; Kumarasamy, A. Phenotypic assessment of safety and probiotic potential of native isolates from marine fish Moolgarda seheli towards sustainable aquaculture. Biologia 2022, 77, 775–790.

- Angulo, M.; Reyes-Becerril, M.; Cepeda-Palacios, R.; Tovar-Ramírez, D.; Esteban, M.Á.; Angulo, C. Probiotic effects of marine Debaryomyces hansenii CBS 8339 on innate immune and antioxidant parameters in newborn goats. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 2339–2352.

- Khalifa, S.A.M.; Elias, N.; Farag, M.A.; Chen, L.; Saeed, A.; Hegazy, M.E.F.; Moustafa, M.S.; Abd El-Wahed, A.; Al-Mousawi, S.M.; Musharraf, S.G.; et al. Marine natural products: A source of novel anticancer drugs. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 491.

- Saeed, A.F.U.H.; Su, J.; Ouyang, S. Marine-derived drugs: Recent advances in cancer therapy and immune signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 134, 111091.

- Zhang, S.; Liang, X.; Gadd, G.M.; Zhao, Q. Marine microbial-derived antibiotics and biosurfactants as potential new agents against catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 255.

- Fenical, W. Marine microbial natural products: The evolution of a new field of science. J. Antibiot. 2020, 73, 481–487.

- Montuori, E.; de Pascale, D.; Lauritano, C. Recent discoveries on marine organism immunomodulatory activities. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 422.

- Ghareeb, M.A.; Tammam, M.A.; El-Demerdash, A.; Atanasov, A.G. Insights about clinically approved and preclinically investigated marine natural products. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2020, 2, 88–102.

More