The future development of forest industries in Russia, besides the country’s geopolitical issues, could be seriously undermined by the depletion of forest resources available under the current model of forest management that mainly relies on clearcutting mature coniferous forests and leaving these areas for natural regeneration. The introduction of a new model that prioritizes efficient forest regeneration faces many problems on the ground. The efficiency of the use of funds allocated by both governmental and private logging companies for forest regeneration and subsequent tending of young stands should urgently be significantly increased. The government should also develop pragmatic economic incentives to encourage logging concession holders to switch to the new model and to address the problem of the spatial shift (demarginalization) of the country’s forest complex from northern and eastern “green fields” to secondary mixed and southern taiga forests. Instead of harvesting low-productivity northern taiga forests of European Russia and remote areas of Central and Eastern Siberia, wood sourcing should be mainly concentrated in the immediate vicinity of existing mills. Moreover, the development of “greenfield” projects in wilderness forest areas that currently lack any kind of infrastructure should not be encouraged. The focus on the regions with productive southern taiga, mixed and broadleaf forests, developed wood-processing infrastructure, and high forest roads density could ensure the economically beneficial transition towards resilient forestry.

- intensive and extensive forestry

- spatial demarginalization of the Russian forest complex

- intact primary forests

1. Introduction

2. How to Promote the Introduction of the Intensive Forestry Management Model in Russia?

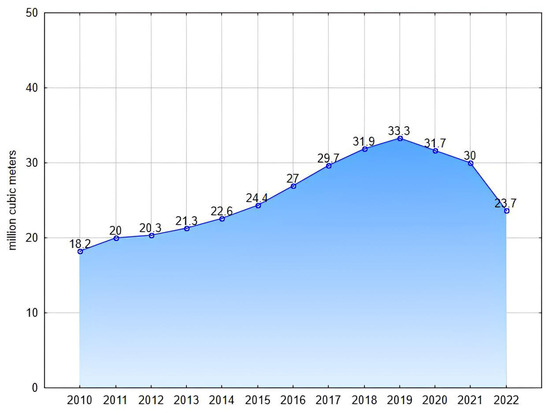

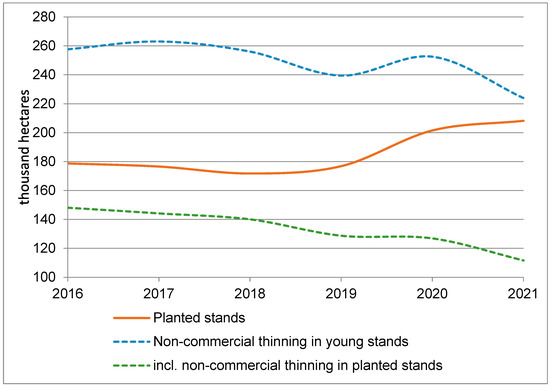

Today, planted forests constitute only one-fifth of the total forest regeneration area in Russia. This means that most clearcut areas, even those lacking a sufficient potential for natural regeneration of commercially valuable tree species, are still left for natural regeneration. In many cases, restoration of coniferous forests takes more than a hundred of years and/or is featured by continuous domination of early successional broadleaved tree species, like birch and aspen. This means that it is necessary to radically revise the requirements for all types of felling, considering all increasing possibilities for the utilization of low-quality timber, including that resulting from thinning operations. Formally, the area of artificial regeneration in Russia has grown in recent years (Figure 2). However, its quality suffers due to poor tending (both agrotechnical and silvicultural) in planted forests. Timely thinning in young stands is critical for the formation of productive coniferous stands. In reality, the total area of non-commercial thinning in young forests decreases and is now equal to the area of artificial regeneration. Moreover, according to the official statistics, only half of all planted forests are thinned. A comparison of the thinning and regeneration area in Russia and Belarus, which initially had a similar forest management system, shows that the ratio between the thinning and regeneration areas in Belarus is 3.9–5.4 times bigger than in Russia [13]. The experience of Sweden and Finland in forestry (Table 1) shows that the area of non-commercial thinning shall be 2–3 times greater than the area of planted forests and/or plantations, since thinning must be repeated several times in the same area to achieve a significant silvicultural effect. A serious problem is the quality of thinning in young forests. To reduce the cost of the forest management plan implementation, concession holders often prefer to perform thinning just along the rows of planted trees (so-called corridor thinning) rather than thinning throughout the whole stand. Corridor thinning mainly produces only an insignificant and very short-lived silvicultural effect because coniferous trees soon become outcompeted by fast-growing early successional broadleaf trees (mainly birch and aspen) growing along the corridor borders. In addition, coniferous trees in rows could be planted too close to each other.

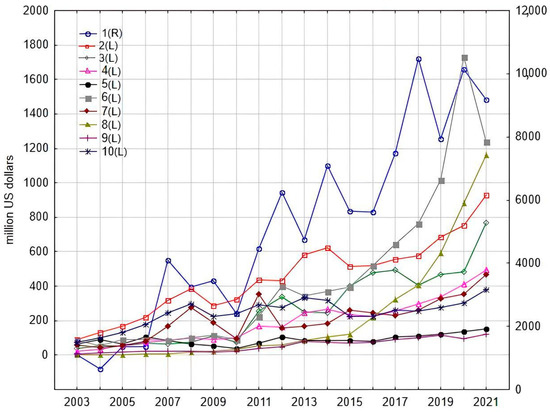

3. Challenge of “Spatial de-Marginalization” of the Russian Forestry Complex

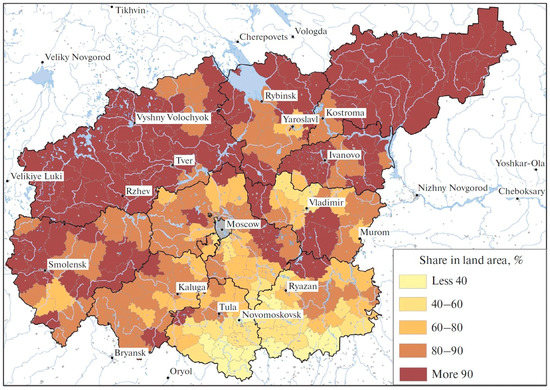

It is obvious that a transition to the IURF model is more beneficial in the regions with a higher natural productivity of forests, a denser network of forest roads, and a developed wood-processing infrastructure. The task of the demarginalization of the Russian forest industries within the forested part of the country is quite an urgent task that includes a shift in main harvesting activities and respective processing infrastructure from low-productivity northern taiga forests of ER and from “greenfield” projects in wilderness forest areas currently lacking any kind of infrastructure in Central and Eastern Siberia to more productive secondary mixed and broadleaf forests (currently dominated by early successional broadleaf species) in southern areas with better climatic conditions with a relatively dense network of roads (67 km per 1000 ha and above). This statement is confirmed by the increasing foreign investments before 2022 in wood processing and production of wood-based panels, sheet materials, etc., by companies like Kronospan (processing facilities in the Republic of Bashkortostan, Moscow and Kaluga regions—a priority investment project in the field of forest development for 2016–2025 was registered in the latter), Egger (processing facilities in Smolensk and Ivanovo regions) and KASTAMONU (processing facility in Elabuga, Republic of Tatarstan) and by an increasing number of birch plywood producers (i.e., Nizhny Novgorod region), etc. These projects and facts seem to be more significant than the “universal” disappointment with the lack of invested billions of dollars and Euros into the construction of new traditional pulp and paper mills, especially given the decline in demand on newsprint and graphic paper grades because of digitalization and growing demand mainly only for packaging materials and products. The regions mentioned above lost their large primary forests a long time ago. They do remain, however, in the specially protected natural areas of the federal level, some of which are even sparsely forested (the forest area of the Republic of Tatarstan occupies 17.5% of the region), but it is obviously compensated for by a significantly greater productivity of the southern belt forests than of the northern taiga [20][21]. At the same time, vertically integrated forest industry companies mainly think in terms of wood supply for already existing industries like sawmills, pulp and paper mills and of the remote and roadless “greenfields” development that requires much more investments than just in building a new pulp and paper mill itself (estimated at USD 2.2 billion). As a result, forestry businesses will sooner or later move to regions with more productive forests and more accessible logistics having a higher road density. In recent years, a strong steady growth in investments into the wood processing (for example, into the production of plywood and wooden housing construction) was observed in the middle and southern parts of ER forest belt, much south of the area dominated by large timber companies, which are usually integrated with the pulp and paper mill built in the Soviet period in Northwestern ER. Additionally, the profitability of investments into the old developed regions of ER should be potentially ensured by gains in logistics [4][5]. In many traditional forestry regions of Russia (Northwestern ER, Irkutsk region), the haulage distance to the railway terminus is 200–300 km, and the secondary forests of the old-developed regions of ER and forests on agricultural lands are often located 10–90 km away from the mill. The strategy of switching to forest concessions and private forests on agricultural lands seems to be more beneficial than the implementation of projects in the remote primary forests of Siberia and the Russian Far East. In the latter, infrastructure is poorly developed and there are high risks of environmental conflicts that could be critical for exporters. The socio-economic effects of intensive forestry on former agricultural lands also seem to be more significant, since every ruble invested into the road infrastructure of the region has cumulative effects on the development of agriculture and recreation and on improving the quality of life in the old developed regions of Russia. The other side of the problem of abandoning the extensive forestry model and moving to the IURF model is the protection of private investments into the improvement of the forest fund and forest management infrastructure, as it ensures a simple and transparent forestry regulatory framework. The obvious solution to this problem is the emergence of private forests on agricultural lands. It does not require any revolutionary political and legal changes since agricultural lands can be privately owned under the current legislation and agricultural production and export are growing in Russia [22] (Figure 3). A significant part of these lands (12% of the country’s agricultural lands) is already in the allocated and delimited property of physical persons (7%) and legal entities (5%), i.e., in real private ownership [23] 21% of agricultural land is in undivided shared properties, i.e., it is in a complicated and slow process of determining a private owner. In fact, to solve the problem of the lack of forest resources, it would be sufficient to ensure legalization and de-bureaucratization of forest management on agricultural lands, around 50–70 million ha of which are abandoned and are being overgrown by forests. From an economic, social, and environmental points of view, forests on agricultural lands should be used for any form of intensive forestry, including plantations and forests for climate regulation [24][25] in compliance with the requirements of fire and sanitary safety rules common to all land categories and requirements for timber trade. A certain exception is probably the management system in former rural forests, which can be equated to protection forests. The logging regime in these should correspond to the category of protection forests, included into the group of “forests that perform functions of protecting natural and other objects”.

- Muhammad Ashraf. Reforming Forest Policies and Management in Russia. Digital Media Time News. https://dmtn1.com

References

- Mordyushenko, O. Forest from Russia Is Delayed. 2023. Available online: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/5998286 (accessed on 25 May 2023). (In Russian).

- Angelstam, P.; Naumov, V.; Elbakidze, M. Transitioning from Soviet wood mining to sustainable forest management by intensification: Are tree growth rates different in northwest Russia and Sweden? Forestry 2017, 90, 292–303.

- Dobrynin, D.; Jarlebring, N.Y.; Mustalahti, I.; Sotirov, M.; Kulikova, E.; Lopatin, E. The forest environmental frontier in Russia: Between sustainable forest management discourses and “wood mining” practice. Ambio 2021, 50, 2138–2152.

- Gerasimov, Y.; Senko, S.; Karjalainen, T. Prospects of forest road infrastructure development in northwest Russia with proven Nordic solutions. Scand. J. For. Res. 2013, 28, 758–774.

- Havimo, M.; Mönkönen, P.; Lopatin, E.; Dahlin, B. Optimising forest road planning to maximise the mobilisation of wood biomass resources in Northwest Russia. Biofuels 2017, 8, 501–514.

- Elbakidze, M.; Andersson, K.; Angelstam, P.; Armstrong, G.W.; Axelsson, R.; Doyon, F.; Hermansson, M.; Jacobsson, J.; Pautov, Y. Sustained yield forestry in Sweden and Russia: How does it correspond to sustainable forest management policy? Ambio 2013, 42, 160–173.

- Naumov, V.; Angelstam, P.; Elbakidze, M. Barriers and bridges for intensified wood production in Russia: Insights from the environmental history of a regional logging frontier. For. Policy Econ 2016, 66, 1–10.

- Sidorova, M.; Trifonova, P. Forest is over. For. Ind. 2016, 12, 17–25.

- Bartalev, S.A.; Stytsenko, F. Assessment of Forest-Stand Destruction by Fires Based on Remote-Sensing Data on the Seasonal Distribution of Burned Areas. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2021, 14, 711–716.

- Shvarts, E.A.; Ptichnikov, A.V. Low-carbon development strategy of Russia and the role of forests in its implementation. Sci. Work. Free Econ. Soc. Russ. 2022, 236, 399–426. (In Russian)

- Kobyakov, K.N.; Shmatkov, N.M.; Shvarts, E.A.; Karpachevsky, M.L. Loss of Intact Forest Landscapes in Russia and Effective Forest Management in Secondary Forests as Its Alternative for Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Rural Development. In Proceedings of the XIV World Forestry Congress, Durban, South Africa, 7–11 September 2015.

- Leskinen, P.; Lindner, M.; Verkerk, P.J.; Nabuurs, G.-J.; van Brusselen, J.; Kulikova, E.; Hassegawa, M.; Lerink, B. Russian Forests and Climate Change. What Science Can Tell Us; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2020; 136p.

- Shvarts, E.; Shmatkov, N.M. Myths and problems of forestry reform in Russia. Obs. Nauk. Sovrem. 2020, 3, 35–53. (In Russian)

- Gustafsson, L.; Bauhus, J.; Asbeck, T.; Augustynczik, A.L.D.; Basile, M.; Frey, J.; Gutzat, F.; Hanewinkel, M.; Helbach, J.; Jonker, M.; et al. Retention as an integrated biodiversity conservation approach for continuous-cover forestry in Europe. Ambio 2020, 49, 85–97.

- Shorohova, E.; Sinkevich, S.; Kryshen, A.; Vanha-Majamaa, I. Variable retention forestry in European boreal forests in Russia. Ecol. Process 2019, 8, 34.

- Petrunin, N.A. Resource and Investment Support of the Russian Forestry Complex in the Context of Economic Sanctions: Presentation for a Speech at the 24th St. Petersburg International Timber Forum, 12 October 2022, St. Petersburg/Nikolay Petrunin. St. Petersburg. 2022. Available online: https://docs.yandex.ru/docs/view?url=ya-disk-public%3A%2F%2Fda8M36cu2BFTP48eqNlYNR39TIeZ0P675B9ydNDjJiDC6adpsSdnb%2Bbe811zbtztq%2FJ6bpmRyOJonT3VoXnDag%3D%3D%3A%2F%D0%9F%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%B7%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%82%D0%B0%D1%86%D0%B8%D0%B8%2012.10.2022%2F%D0%9B%D0%B5%D1%81%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B5%20%D1%85%D0%BE%D0%B7%D1%8F%D0%B9%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B2%D0%BE%2F10.30%20%D0%9D%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B9%20%D0%9F%D0%B5%D1%82%D1%80%D1%83%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BD.pdf&name=10.30%20%D0%9D%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%B9%20%D0%9F%D0%B5%D1%82%D1%80%D1%83%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BD.pdf&nosw=1) (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Kotel’nikov, R.V.; Lupyan, E.A.; Bartalev, S.A.; Ershov, D.V. Space Monitoring of Forest Fires: History of the Creation and Development of ISDM-Rosleskhoz. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2020, 13, 795–802. (In Russian)

- Kovalev, N.A.; Loupian, E.A.; Balashov, I.V.; Bartalev, S.A.; Burtsev, M.A.; Ershov, D.V.; Krivosheev, N.P.; Mazurov, A.A. ISDM-Rosleskhoz: 15 years of operation and evolution. Sovrem. Probl. Distantsionnogo Zondirovaniya Zemli Kosmosa 2020, 17, 283–291. (In Russian)

- Men, M.A.; Morokhoeva, I.P. Report on the Results of the Control Activities “Checking the Efficiency of Forest Resources Use and Budgetary Funds Aimed at the Implementation Authorities of the Russian Federation in the Field of Forest Relations in 2016–2018 and the Past Period of 2019” (Jointly with the Control and Accounting Authorities of the Constituent Entities of the Russian Federation). 2020. Available online: https://ach.gov.ru/upload/iblock/615/615ed6c35deb0be824f57b74225f601c.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020). (In Russian)

- Pisarenko, A.I.; Strakhov, V.V. Forestry in Russia: From Use to Management; Jurisprudence: Moscow, Russia, 2004. (In Russian)

- Shvidenko, A.Z.; Schepashchenko, D.G.; Nilsson, S.; Buluy, Y.I. Tables and Models of Growth and Productivity of Forests of Major Forest Forming Species of Northern Eurasia (Standard and Reference Materials); Federal Forestry Agency: Moscow, Russia, 2008. (In Russian)

- Kirilenko, A.; Dronin, N. Recent grain production boom in Russia in historical context. Clim. Change 2022, 171, 22.

- State (National) Report on the State and Use of the Lands of the Russian Federation in 2019, 2020, n.d. Moscow, Russia. Available online: https://rosreestr.gov.ru/site/activity/gosudarstvennyy-natsionalnyydoklad-o-sostoyanii-i-ispolzovanii-zemel-rossiyskoy-federatsii/ (accessed on 15 March 2021). (In Russian)

- Griscom, B.W.; Adams, J.; Ellis, P.W.; Houghton, R.A.; Lomax, G.; Miteva, D.A.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Shoch, D.; Siikamäki, J.V.; Smith, P.; et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11645–11650.

- Moreau, L.; Thiffault, E.; Cyr, D.; Boulanger, Y.; Beauregard, R. How can the forest sector mitigate climate change in a changing climate? Case studies of boreal and northern temperate forests in eastern Canada. For. Ecosyst. 2022, 9, 100026.

- Averkieva, K.V. Symbiosis of agriculture and forestry on the early-developed periphery of the non-black earth region: The case of the Tarnogsky district of the Vologda region. Russ. Peasant Stud. 2017, 2, 86–106. (In Russian)

- Lesiv, M.; Schepaschenko, D.; Moltchanova, E.; Bun, R.; Durauer, M.; Prishchepov, A.; Schierhorn, F.; Estel, S.; Kuemmerle, T.; Alcantara, C.; et al. Spatial distribution of arable and abandoned land across former Soviet Union countries. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180056.

- Medvedev, A.A.; Telnova, N.O.; Kudikov, A.V. Remote highly detailed monitoring of the dynamics of overgrowing of abandoned agricultural lands with forest vegetation. Vopr. Lesn. Nauki 2019, 2, 1–12.

- Shvarts, E.A.; Kazantsev, N.N.; Baybar, A.S. Rational use of abandoned agricultural land: One step forward, two steps back. Sustain. For. Manag. 2021, 1, 7–12. (In Russian)

- Medvedev, A.A. The Fields and Farms of Central Russia as Seen from Space. Reg. Res. Russ. 2022, 12, S65–S73.

- Dobrynin, D. Management of state forests in Finland and Sweden. Sustain. For. Manag. 2019, 12, 14–17. (In Russian)