Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Kristijan Robert Prebanic and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

The world is experiencing a major cycle of investment in infrastructure, which is essential for the development and prosperity of countries and societies. Management failures in infrastructure projects are widely known, and some of them involve the weak engagement of project stakeholders. The importance of stakeholder involvement as a key factor in the success of infrastructure projects is widely recognized.

- stakeholder

- engagement

- project success

- factors

- criteria

1. Introduction

In recent years, large infrastructure projects, used as the main tool to overcome existing infrastructure capacity problems or to create new business opportunities, have been of great importance for the development of society and economy [1][2][1,2]. Infrastructure projects create a capacity for the transportation, transmission, distribution, collection, and interaction of goods, services, or people (e.g., pipelines, highways, bridges) [3][4][5][3,4,5]. In addition to civil infrastructure, there is another type of urban infrastructure, social infrastructure [6], which is also necessary for the development of society and enables the promotion of cultural norms and a healthy population (e.g., courts, schools, hospitals) [7][8][7,8]. Both types of projects share similar characteristics: a complex environment with numerous interested parties, public clients covered by national public procurement rules, and often relatively large investments [6][8][6,8], although civil infrastructure sometimes implies mega-projects, which is not the case for social infrastructure. Infrastructure projects are being undertaken all over the world today, whether in developed countries that are expanding their infrastructure capacity or in developing countries that are building vital infrastructure for the first time [9]. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that the world will need to spend $57 trillion on infrastructure by 2030 [10].

The high complexity associated with stakeholders with conflicting interests can lead to time and cost overruns, and there are prominent cases that illustrate this problem [11][12][11,12]. Many argue that the performance of these projects is unsatisfactory: the wrong projects are selected, costs are underestimated, and benefits are overestimated [13]. More general research shows that about 70% of companies undertake projects that neither satisfy the stakeholders nor achieve the planned objectives [14][15][14,15]. Brunet and Aubry [16] noted that the anatomy of large public projects is changing with increasingly complex stakeholders and supply chain linkages and called for increased scientific study of this new organizational phenomenon. Luo et al. [17] concluded that conventional project management approaches are not sufficient to achieve successful project outcomes in complex infrastructure projects.

Multiple Stakeholder Engagement Issue–Vague Understanding of Stakeholder Engagement Process and Organizational Enablers in Infrastructure Projects

According to stakeholder management theory, projects are successful when they take into account the needs and requirements of stakeholders through the process of stakeholder management [18]. There has been a shift in projects and organizations to be more socially and environmentally responsible by involving broad and heterogeneous networks of stakeholders to create system-wide benefits [18][19][20][18,19,20]. The project management approach is transforming from a “predict-and-control” strategy to a “prepare-and-commit” strategy to foster collaboration among stakeholders [21]. Stakeholder involvement in construction projects is a critical factor for successful project delivery [22], and yet little is known about how to promote it in projects [23]. There are two main approaches used in studies to examine the nature of stakeholder engagement in complex construction and infrastructure projects.

The first approach deals explicitly with the stakeholder management process. There are many works that address the stakeholder engagement process and practices as part of a comprehensive stakeholder management approach [24][25][26][27][28][29][24,25,26,27,28,29]. Chinyio and Akintoye [24] examined stakeholder engagement practices in construction projects, classifying two approaches (overarching and operational approaches) and the activities embedded within them (i.e., high-level support or effective use of communication and negotiation). Yang et al. [25] established a typology of operational approaches to stakeholder analysis and participation (e.g., public presentation…), and other studies linked the stakeholder participation process to the concept of sustainability to explore how to build trust and facilitate the participation of broader stakeholder groups that have often been neglected [28][29][30][28,29,30]. More recently, ICT technologies have also been explored as tools to facilitate stakeholder engagement [15][31][15,31] and improve collaboration among engaged stakeholders [32][33][32,33]. Social media and various web applications provide opportunities to accelerate the engagement of broader stakeholder groups [34][35][36][37][34,35,36,37], while BIM and the digital twin serve to improve collaboration among internal project stakeholders [38]. However, there was little evidence of projects applying these formally developed approaches to stakeholder engagement. Few recent studies have examined the use of stakeholder engagement processes and practices and have shown that they are used very little or not at all; even in developed countries such as the UK [27][39][27,39] and Australia [40], the use is very low or non-existent.

The second type of studies deals with stakeholder engagement from the perspective of organizational, complexity, and institutional theory [16][17][41][42][16,17,41,42] and the concept of project governance, which is closely related to the above theories [43][44][45][46][43,44,45,46]. Developed countries such as Norway and the United Kingdom have introduced governance frameworks (i.e., phase gates, audits and reviews, etc.) to deal specifically with the complex nature of large public infrastructure projects [16][42][16,42] and have used engagement as part of this framework. Khan et al. [44] tested and proved that project governance mechanisms such as transparent reporting and effective use of the public project sponsorship approach improve project performance, which is further enhanced by implementing a stakeholder management process. The characteristics of good project governance are consistent with the principles of stakeholder engagement [45]: active participation (e.g., making the right decision at the right time); project control to achieve strategic goals and satisfy stakeholders; and the promotion of equity in the sense that all parties have equal opportunities to improve or maintain their own well-being. Klakegg et al. [46] emphasized that governance frameworks represent progress in managing complex infrastructure projects but concluded that they are still poorly understood in terms of organization.

Many agree that stakeholder engagement is of paramount importance in large infrastructure projects [22][44][47][48][22,44,47,48], and yet stakeholder engagement is poorly implemented. There have been few attempts to capture the complex nature of the stakeholder engagement process. Pascale et al. [18] analyzed 98 projects and found that engagement practices have been adequately explored only for the front-end phases, while Collinge [49] applied a case study approach and concluded that stakeholder engagement is a complex, intertwined process of responsibility, organizational actions, and work package requirements and is a fundamentally unexplored area of construction project management.

2. Achieving Project Success in Large Construction and Infrastructure Projects

The results of several studies show that project success is a multidimensional concept: it means different things to different people, and context is crucial for evaluating project success [50]. It is often concluded that project success is a complex concept that has evolved over time [51]. In the field of project success, there are two main aspects of success that are studied as separate but related research topics: success factors and success criteria [52]. Success factors are defined by Muller and Turner [53] as project elements that can be influenced to increase the likelihood of success, and success criteria are fundamental elements that rwesearchers use to measure success. An important aspect of success is the point in the project (or product) life cycle at which researcherswe measure success, as it influences theour evaluation [54][55][54,55]. One of the earlier and best known models of project success is that of Pinto and Slevin [56]. It consists of two main criteria: success from the project’s point of view, consisting of time, cost, and technical performance, and success from the client point of view, consisting of utility (usability of the project delivery), client satisfaction, and effectiveness (usefulness for improving the client’s future business) [56]. More recent models have a similar logic, i.e., project management success and project success [50] or project success and project product success [51]. The next step in this direction was taken by Turner and Zolin [55], who fully considered the stakeholder theory point of view and presented a success model that considers success for eight main types of project stakeholders (e.g., clients/customers, end users, public, contractors/suppliers, etc.). The model [55] also elaborates specific success criteria for each stakeholder separately and divides them into three different measurement periods. Albert et al. [51] defined six different research areas, i.e., six industries in which success factors and criteria (and their interrelationship) should be studied separately, and one of them is “design and construction of building facilities”. Several specific characteristics are given for construction projects:-

Unique physical product

-

Long planning phase and project duration

-

Material costs exceed labor costs

-

Stationary location of project execution

-

Detailed specifications with many standards, norms, and regulations to be met

-

Plan-oriented approach to design and implementation

Table 1. Project success research with different views on success criteria of construction projects and their main characteristics.

| Name/Description of Success Model (Author and Year of Published Article) | Construction Stakeholder Type Which Perspective was Considered | The Category of Success Criteria and the Number of Associated Success Criteria or Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Success criteria of buildings projects (Al-Tmeemy et al., 2011) [61] | Contractors (project) perspective | Project management success (3 criteria) Product success (3 criteria) Market success (4 criteria) |

| Project success criteria (Williams 2015) [60] | Contractors (organization) perspective | Was the final product good? (3 measures/criteria) Were the stakeholders satisfied with the project? (5 measures/criteria) Did the project meet its delivery objectives? (3 measures/criteria) Was project management successful? (6 measures/criteria) |

| Dimensions of project value (Vuorinen and Martinsuo, 2019) [63] | Perspective of public client/government and wider society | Social and environmental value (descriptive) Financial value (descriptive) Systemic value (descriptive) |

| KPIs for assessing construction megaproject success (He et al., 2021) [57] | Perspective of public client/government | Project efficiency (3 KPI) Key stakeholders’ satisfaction (2 KPI) Organizational strategic goals (2 KPI) Comprehensive impact on society (2 KPI) |

3. Engagement of the Project Stakeholders as Critical Success Factor for Infrastructure Projects

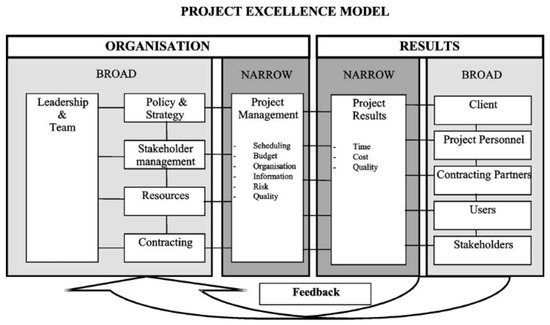

Westerveld’s success model [67] (i.e., the Project Excellence Model, Figure 1) was the first model to systematically link project success factors to success criteria. This model introduced the critical success factor of stakeholder management [67], which combined several of the aforementioned success factors (e.g., consultation, communication, etc.) into one management function.

Figure 1. The Project Excellence Model.

-

Inform: Provide stakeholders with balanced and objective information that helps them understand issues, alternatives, and/or solutions.

-

Consult: Solicit stakeholder feedback on the analysis, alternatives, and/or decisions made.

-

Involve: Work directly with stakeholders throughout the process to ensure that their concerns and desires are consistently understood and addressed.

-

Collaborate: Work in partnership with stakeholders on every aspect of the decision.

-

Empower: Place final decision making in the hands of stakeholders.

Digital Approach to Engagement and Collaboration of Project Stakeholders

Chung et al. [31] developed an innovative collaborative framework approach based on ICT technologies to broaden stakeholder engagement and participation in construction mega-projects briefing. Yazicoglu [78] studied BIM in a multi-stakeholder environment and concluded that the main challenges to the adoption of BIM are supplier compatibility with BIM, the need for two-dimensional drawings, and contractual issues related to BIM. Similarly, Sharafat et al. [79] developed a novel BIM-based multi-model tunnel information model (TIM) that facilitates data sharing, information integration, data accessibility, etc. to improve construction project management. A study investigated the impact of VR-based design review actions and proved that it helps construction stakeholders collaborate effectively and understand information better [80]. Most examples of digital engagement focus on collaboration on practical tasks between internal stakeholders, and examples of the successful implementation of ICT systems are scarce [15]. Scholars emphasized that public clients and others involved in construction need to redesign their organizational processes [15] and improve their digital capabilities [81] to reap the proclaimed benefits of digital project management.4. Complex Context of Infrastructure Projects–Enabling Engagement through Specific Project Governance and Management Mechanisms

The traditional approach, based on the technical aspects of the project, is proving relatively ineffective for modern large-scale technical projects with multiple stakeholders, which are an increasingly common mechanism for delivering critical infrastructure [82]. Winch [83] offered a two-tiered classification of stakeholders in construction that reflects the diversity of interests involved in projects: internal stakeholders who are in a legal contract with the client and external stakeholders who are affected in some way by the project. Internal stakeholders can be divided into the demand side (e.g., sponsors, clients of the client) and the supply side (e.g., contractors, designers), while external stakeholders can be divided into private (e.g., the local community) and public (e.g., regulators, local authorities) [83]. One of the research topics closely related to project management and appropriate involvement of key project stakeholders is “project governance”, and this function is also related to organizational aspects of project management such as project portfolios and project sponsorship [84][85][84,85]. Many authors state that project governance mechanisms naturally complement the project management function, i.e., provide the framework and rules for managing (infrastructure) projects [44][82][86][44,82,86]. The following definition of “project governance” describes its purpose as “…a set of management systems, rules, protocols, relationships, and structures that provide a framework within which decisions for the development and execution of projects are made to achieve the intended business or strategic motivation” [87]. Klakkeg et al. [88] emphasized that understanding the “project governance framework” is vital for choosing methods and tools for project management. Some developed countries have developed governance frameworks for public (infrastructure) programs and projects to professionalize public project management and rationalize public procurement costs, and one of the first and most important models is the 2001 OGC Gateway Review Process developed in the UK [89][90][89,90]. This model was adopted (and adapted) by Australia and New Zealand in 2006 and 2007, respectively [89][91][89,91]. Klakegg et al. [46] analyzed and compared different systems, i.e., frameworks for the governance of public infrastructure projects from three developed European countries (e.g., Norway, Netherlands, UK) and summarized the main features:-

Phase gates with documentation requirements and comprehensive audits, especially very early consultations-initial gates (UK, NL) and use of external consultants from the private sector as external auditors (UK, NO)

-

Focus on needs and a more robust, clearer, and broader basis for planning in the early stages (“front-end planning”)

Croatian Administrative and Organizational Context for Infrastructure Project and Engagement of Project Stakeholders

Since joining the European Union in 2013, mainly thanks to the European Union’s Cohesion Policy, Croatia has had very substantial financial resources, a large part of which has been allocated to the construction or reconstruction of infrastructure [93][94][93,94]. Public legal acts and bodies are an indispensable part of all (infrastructure) projects co-financed by the EU, and the tasks of each body are defined in the following official documents:-

Act on the establishment of an institutional framework for the implementation of European structural and investment funds in the Republic of Croatia in the financial period 2014–2020 [95].

-

Several government regulations defining the responsibilities of each body for each European Structural Instrument (ESI), e.g., the Regulation on the bodies in the management and control systems for the use of the European Social Fund, the European Regional Development Fund and the Cohesion Fund in relation to the “Investment for Growth and Jobs Objective” [96].

-

Extensive and early stakeholder involvement (NL)

-

Establish its own system for project implementation (implementation of activities) and update and, if necessary, detail the project implementation plan provided for in the project proposal;

-

Update and, if necessary, detail the schedule provided for in the project proposal and update the responsibilities for the implementation of the project activities…;

-

Areas of project implementation monitoring include:

- ○

-

Systematic updating and monitoring of the project implementation plan

- ○

-

Management of the project team

- ○

-

Management of outputs and results

- ○

-

Project procurement management

- ○

-

Human resource management

-

Active risk management, independent review of cost estimates, and use of reserves in budgets to protect against uncertainty and avoid cost overruns (UK, NO)

-

Professionalize public project sponsors in managing projects and programs and in public procurement by tightening requirements, systems, training, and issuing administrative and management guides.

- ○

- Risk management

- ○

- Management of information dissemination and visibility