1. Introduction

Reliable energy sources are crucial for residential grids, yet renewable solutions like photovoltaic (PV) systems experience irregular power production contingent on resource availability

[1]. To address this, this study proposes coupling PV with battery and Micro-cogeneration units as a holistic energy-generation solution. Notably, the incorporation of a Micro-cogeneration system, particularly a Micro combined heat and power (Micro-CHP) system powered by an internal combustion engine, presents a potential pathway towards off-grid residential energy solutions. Micro-cogeneration units are versatile systems producing both electrical and thermal energy. Despite their relatively small size (under 50 kW), they offer opportunities to reduce primary energy consumption and curb greenhouse gas emissions

[2][3][4][5].

Utilizing the mechanical energy generated by the internal combustion engine converted by an alternator and the thermal energy harvested from the engine’s exhaust gases and cooling circuits, these systems can contribute to overall efficiency

[6]. Micro-cogeneration presents an opportunity to enhance the stability and resilience of home grids powered by renewable energy sources, thereby overcoming the implementation barrier that arises from relying solely on renewables. By integrating Micro-cogeneration, home grids can become more energy efficient and resilient. PV panels and battery systems sometimes fall short of consistently meeting the demands of the household grid, particularly during periods of low solar exposure. This current

presea

perrch proposes that the internal combustion engine in the Micro-CHP system can function as a backup in these instances, supporting electrical demand and charging the batteries while also providing thermal energy for applications such as hot water and space heating. It is intended to analyse and state that the Micro-CHP can support both demands (kW) in integrated grids with PV and battery systems, aiming to keep them off-grid. The challenges associated with implementing this system can be attributed to factors such as the fuel supply network, acquisition costs, maintenance requirements, and adaptation to imposed loads. Overcoming these challenges is crucial for the successful implementation of such a system. This study aims to address these challenges by effectively integrating the electrical production of the Microgeneration system with the imposed load requirements, particularly in the context of photovoltaic energy, where renewable energy production may be limited.

It is important to establish a framework that enables the fulfilling of load requirements imposed on the network while effectively predicting and meeting the thermal demands for domestic hot water and residential heating. To achieve this objective, it aims to employ appropriately sized machines, coupled with prediction networks and energy storage systems. This integrated approach allows for more accurate and efficient management of the system, ultimately mitigating and satisfying the imposed needs. By utilizing advanced prediction technologies and optimizing energy storage, the demands placed on the system can be effectively suppressed, ensuring a reliable and efficient operation. To optimize the operation of the proposed system, machine learning techniques are employed. Specifically, artificial neural networks (ANNs) are used to predict the electrical load and PV power based on the load profile and PV production of the previous day. This innovative approach allows for the proactive planning and control of electrical and thermal energy, enhancing network safety and efficiency. The main challenge, then, is to efficiently interconnect and coordinate these diverse technologies within the network.

2. Micro-Cogeneration Systems with Internal Combustion Engines

Micro-CHP systems featuring internal combustion engines (ICEs) have emerged as the preferred choice for small-scale applications, owing to their robustness and time-tested technology

[7]. Nevertheless, regular maintenance is crucial for maintaining their operational viability

[8]. These systems demonstrate versatility in terms of fuel use and can be adapted to fulfil the electricity and heat requirements of the infrastructure where they are deployed

[9].

The energy yielded from the fuel is apportioned into three parts: approximately one-third is converted into mechanical work, another third dissipates as heat in the exhaust gases, and the remaining third is manifested as internal engine heat losses. Some of these heat losses occur due to various heat transfer mechanisms within the engine’s cooling circuit

[6].

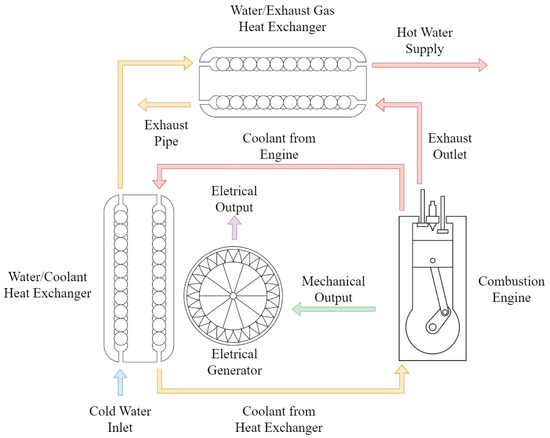

When implemented into Micro-cogeneration, internal combustion engines generally adopt a standard configuration as depicted in

Figure 1. The system’s constituent elements comprise an engine, a generator, a heat recovery system—including a water jacket and exhaust gas heat exchangers—and an acoustic isolator. The engine propels the generator through its mechanical energy, while the heat exchangers recover thermal energy from the engine’s exhaust system and cooling circuits. A pump typically drives the heat recovery system, prompting the coolant to circulate through the engine and into the heat exchangers, consequently producing hot water

[8].

Figure 1. Standard configuration of a Micro-CHP system based on ICE.

Several brands have developed Micro-CHP systems based on internal combustion engines. Honda pioneered the market in 2003 with the Ecowill Micro-CHP unit, selling 100,000 units in Japan

[6]. This natural gas-powered unit marked the first Micro-cogeneration system designed with an internal combustion engine, offering 1 kW of electrical power and 3 kW of thermal power with an overall energy efficiency of 85%

[10]. An upgraded model launched in 2011 boasted an enhanced overall efficiency of 92% due to the application of the “EXlink” engine, which features an expansion stroke longer than the compression stroke thanks to a multi-link expansion linkage mechanism

[11]. Other notable entries into the market include Tokyo Gas’s natural gas-powered 6 kW system with an efficiency of 86% and Yanmar Diesel Engine Co.’s system offering an output of 9.8/8.2 kW, with an efficiency of 81.55% and a heat recovery rate of up to 58/56%

[8][12].

In Europe, SenerTec dominates the market, with over 20,000 units sold of their Dachs model, which offers 5.5 kW of electrical power, 10 kW of thermal power, and an overall efficiency of 90%

[6][8]. A notable alternative comes from PowerPlus Technologies, which has introduced the Ecopower Micro-CHP unit, providing adjustable electrical power ranging from 4.7 to 1.3 kW thanks to engine rotation control and a frequency converter that conditions the energy output for grid feeding. The unit’s thermal power ranges from 4 to 12.5 kW, with overall efficiency estimated at 89%

[6].

3. Micro-Cogeneration Systems with Fuel Cells

Fuel cells are devices that produce electrical and thermal energy from chemical energy, without involving combustion cycles. Hydrogen (fuel) and oxygen (oxidant) are the chemical elements used to obtain the two forms of energy. Fuel cells are classified according to their working temperature or the type of electrolyte. The most suitable for cogeneration systems are alkaline fuel cells (AFCs), proton exchange membranes (PEMs), phosphoric acid fuel cells (PAFCs), molten carbonate fuel cells (MCFCs), and solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs)

[13]. Their use in Micro-cogeneration has advantages such as low emissions, high efficiency, low noise, and greater autonomy, creating independence from the grid

[14]. The complex processing or access to hydrogen, the time-consuming start-up, and the complexity of integration in hybrid systems are the main barriers to the introduction of this technology in Micro-cogeneration

[15].

4. Challenges in Integrating Micro-Cogeneration into Residential Grids

Incorporating an internal combustion engine within the framework of Micro-cogeneration into residential settings with existing photovoltaic panels and batteries poses significant challenges. The primary hurdle is the effective interconnection of all energy systems, aiming to optimize grid profitability while minimizing losses and costs. Consequently, sophisticated and automated control systems are paramount for effective energy management

[16].

Darcovich et al. scrutinized a residential grid comprising these technologies and emphasized that utilizing photovoltaic panels and batteries could yield economic benefits, albeit to a lesser extent upon the integration of a Micro-CHP system

[17]. The energy consumption hierarchy generally prioritizes photovoltaic power due to its renewable nature, followed by battery usage, and finally, engine operation when the photovoltaic power and battery charge level prove inadequate.

For water heating applications, photovoltaic power is the primary energy source. However, when it falls short, the engine’s thermal energy steps in. Compared to conventional water heaters, engines cannot heat water as rapidly, leading to the inclusion of a water cylinder in the system. This component provides a time buffer between the heat produced by the Micro-CHP and the hot water utilized

[18].

The complexity arises in deciding where to direct the electrical energy and establishing criteria for using the engine’s thermal energy. Further complications could stem from the time taken to charge the battery while the engine simultaneously supports the residence’s electrical load. These issues exemplify some of the potential difficulties faced when amalgamating these technologies within a unified grid

[17].

5. Machine Learning and Control Strategies for Energy Management

Addressing the significant electricity demand from off-grid sources has made energy management a pressing issue in residential settings. Several innovative approaches have emerged, using machine learning and control strategies to manage energy systems effectively, balancing energy distribution, and optimizing the use of photovoltaic panels, batteries, and internal combustion engines in Micro-cogeneration. These strategies strive to decrease energy consumption and enhance overall system performance.

Machine learning models extensively utilized in energy systems include artificial neural networks (ANNs), multilayer perceptron (MLP), extreme learning machine (ELM), support vector machines (SVMs), wavelet neural networks (WNNs), adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFISs), decision trees, deep machine learning, ensemble models, and hybrid advanced machine learning models.

ANNs serve as a framework for various machine learning algorithms designed to process complex data inputs and can be applied to prediction, regression, and curve-fitting methodologies. Their simplicity when faced with multi-variable problems makes them stand out

[19]. MLPs are a more sophisticated variant of ANNs, often referred to as feedforward neural networks, widely used in process modelling and prediction

[19][20][21].

An SVM, on the other hand, is particularly suitable for pattern recognition, classification, and regression analysis due to its ability to execute generalizations. Its algorithms, based on statistical learning theory for structural risk minimization, find wide applicability in load forecasting

[22].

A WNN leverages a function to process a data series and yield an output value for a specific input value. This model requires less learning time compared to the MLP model

[23]. The ANFIS methodology is a fusion of fuzzy logic and neural network features, integrating an ANN based on the Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy inference system, marking it as a hybrid machine learning method

[24]. Decision trees utilize a tree-like model to make decisions based on historical electric load data. Deep machine learning employs deep neural networks to predict load based on past data, allowing for more precise future load predictions due to its ability to learn complex, non-linear patterns. Ensemble techniques amalgamate multiple prediction models into an overarching model to enhance prediction accuracy. Finally, hybrid advanced machine learning models combine decision trees and deep neural networks to accomplish highly accurate load forecasting

[22].