Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Ana Ibáñez-Hernández.

This research addresses the scientific production of pharmaceutical communication in Spain around the COVID-19 crisis, in which information overload, amplified by the digital media, evidenced the relevance of communication in the digital society.

This research addresses the scientific production of pharmaceutical communication in Spain around the COVID-19 crisis, in which information overload, amplified by the digital media, evidenced the relevance of communication in the digital society.

- pharmaceutical communication

- health literacy

- digital society

- coronavirus

1. Communication and Health

Communication processes acquire special relevance when applied in the field of health, with them having a direct consequence on people’s well-being and quality of life. Such processes are present in the doctor–patient relationship, but they are also present in those forms of communication produced by different organisations, either public or private, which have effects on a larger scale.

Health and communication studies gained strength at the end of the 20th century [1,2][1][2]. In doctor–patient matters, this is an incipient research field, which authors confirm with an increase in the number of study studies that, coinciding with the turn of the century, allow an improvement in the effectiveness of communication between doctors and patients, paying greater attention to doctors’ communication skills and to patients’ needs for information, as well as to the context in which health interaction occurs [2].

Studies on doctor–patient communication [3] are beginning to “take into account the psychosocial aspects of patients, adapt to their needs, to the different stages of the treatment” (p. 28) in order to achieve greater efficacy, satisfaction and adherence to such aspects. Thus, according to the authors of [3], contrary to traditional paternalism in medical practice, at the end of the 70s, the idea of the competent patient arose, which is linked to the concept of self-efficacy. In the current context of globalisation, this consideration takes on special relevance, as health information of all kinds has a place in a hyperconnected society. The idea of the self-management of one’s own health is supported by patients’ easy access to information that affects them. The patient-public now has direct ways to form a prior opinion on their health problems, which eventually changes the traditional forms of communication with health professionals authorised to look after patients’ health.

At the same time, although its application is of special relevance in the current context of information overload, the idea of health literacy confined to health education and that has direct consequences for disease prevention and people’s quality of life [4] is beginning to emerge. The World Health Organisation [5] consolidates the concept in the Ottawa Charter of 1986, defining it as “the cognitive and social skills which determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health”. So, health literacy is a process that empowers people, enabling them to make better decisions on health issues and to prevent individual or collective diseases [6].

In close relation to the field of prevention, and as a paradigmatic example of social communication addressed to a large number of people, communication for the promotion of health is recognised as a necessary mechanism for improving health, either public or personal [7]. Here, it is noticed that assuming the possibility of carrying out campaigns for health promotion implies positioning oneself close to the paradigm of communication for social change [8]. As a consequence, defending the importance of this type of communication also implies attributing the property of impacting society to it. In addition, it is this impact that leads us to reflect on the type of communication that the pharmaceutical industry develops, with the use of other marketing and advertising techniques, for any purpose.

2. Communication and the Pharmaceutical Industry

The pharmaceutical industry generates around EUR 1.4 trillion per year around the world, an amount that could exceed EUR 1.6 trillion in the next 6 years [9]. In Spain, it exceeded EUR 22,000 million in 2020, according to 2022 data [10], generating more than 47,000 jobs in the country and with annual exports above 12,000 million. It is therefore one of the most powerful and competitive sectors of the Spanish and global economy that, due to the needs inherent to its industrial activity, invests large sums in R&D, contributing to scientific progress, global health and social progress.

Given its social and economic implications, the pharmaceutical industry is subject to strong regulatory and organisational limitations, where all communication channels are not always possible and where most of its products are prohibited from advertising. Therefore, to guarantee a safe, rational and effective use for each patient, the Royal Decree 1416/1994 of 25 June defines what is advertising and what is not regarding pharmaceutical products. This regulation expressly prohibits the advertising of any medicinal product for human use that must be prescribed by a doctor, namely all those containing psychotropic or narcotic substances and the entire catalogue of medicaments included in the provision of the national health system [11]. Exceptions to this rule are consumer health care (CHC) products, which, without exemption from the control and requirements established by the competent health authorities at the national and European level, have greater freedom and promotion, since they are products that are not subject to state funding, they are free of psychotropic or narcotic substances or they do not require a doctor’s prescription or follow-up. In this sense, the same legislative text recognises advertising for people who can prescribe and dispense medicines as communication. “They are products that require medical prescription, and this condition also affects the public to which they should be addressed, that is, the message should be addressed to doctors, not to the patient” [12] (p. 98).

Article [12] also regulates the relationships established between the doctor and the medical representative, and it states that “the medical representative’s visit is the means of relationship between laboratories and the people empowered to prescribe or dispense medicines for the purposes of information and advertising such medicines” [11] (p. 5). Likewise, it also regulates some type of incentive, such as sending free samples, and other frequent relational practices in the sector, such as sponsoring scientific events, as “other forms of advertising”. Therefore, given the impossibility of freely promoting certain pharmaceutical products, manufacturers tend to strengthen their brands to generate confidence through alternative techniques such as public relations or training for commercial and advertising purposes [13].

Consequently, disciplines such as public relations, advertising or digital marketing make the sector face a great ethical dilemma. However, while pharmaceutical companies often refer to standards and ethical codes such as those of the WHO [14], the same attention is not paid to those who use the medicines, even at the risk of encouraging self-consumption [15]. These authors warn that the rest of the promotional activities are not closely monitored, even confusing concepts such as promotion, advertising and medical information in their terminology to facilitate the mass diffusion of pharmaceutical products in a disguised way.

This terminological confusion is produced to the detriment of the transparency in pharmaceutical promotion, and it is understood as veracity and responsibility in its diffusion, since the aim is that consumers are well informed of the benefits and possible risks related to their pharmacological treatments [13]. This premise, the authors continue, is based on the assumption that patients in general do not have sufficient knowledge to discern the veracity of an advertising message about medicaments. At this point, health literacy is as important as literacy in advertising and in any other form of promotion for which it is not possible to ignore the transformation in the communicative processes that new technologies have posed.

In any case, the interdisciplinary essence of communication in the field of health is necessary to guarantee its effectiveness, since the success of health promotion campaigns is also conditioned by the knowledge of theories and behavioural trends of cultural and structural circumstances as well as by the knowledge of social and cultural trends of socio-health aspects, of the available health system and, in particular, of a deep knowledge of the publics and their perceptions of health [7]. Based on the public map proposed by the World Health Organization [16] to improve the effectiveness of its communication with the main recipients of its messages and thus protect the health of individuals and societies in the different countries in which it operates, it is necessary, therefore, to apply the situational theory of publics [17] in the pharmaceutical context. In this sense, the map of publics and agents for the pharmaceutical reality is adjusted to the diversity and communicative complexity in the medicine chain, as it is a system that interrelates the many actors in the sector and affects publics of different nature and with different communication needs [18]. For these authors, this relationship with society as a whole and, more specifically, with agents and publics such as the group of health professionals—pharmaceutical manufacturers, distribution companies, political authorities and regulatory agents, patient-consumers, patient associations, pharmacies and pharmaceutical offices [18]—emanate from different links and require a different communicative approach.

3. Communication and the Digital Environment

The emergence of the Internet introduced a new open and two-way communication channel with the final recipient of the pharmaceutical product. This allowed the agents involved to find new ways of disseminating and promoting their products, which citizens could access with a click. This made the volume of pharmaceutical content of a varying nature, which went far beyond the publication of the prospectus, shoot up in the digital environment. In the sea of the Internet, the sector navigates with a greater impunity than in the brick-and-mortar pharmacy. Electronic media can be very practical in spreading health issues among the population and achieve greater and more effective health promotion among citizens [19]. However, it is also a challenge for health professionals who have to acquire communicative skills to use mobile applications that provide scientific information about a treatment, to make a video and use it in health promotion and to keep up to date with digital resources to provide reliable health information to a patient or connect with other professionals online. Additionally, all this information on the Internet and social media has added greater complexity to this situation even before a user, who usually lacks the necessary training, is able to distinguish it properly.

Patients, overwhelmed by information, can check their maladies online, contrast opinions with other Internet users or receive the impact of health influencers. All this results in the idea that individuals, by themselves, can self-manage their health care, find out information by themselves and even give opinions or discern about the most appropriate treatments to heal the pathologies affecting them and improve their quality of life, without the need to visit a doctor or consult a pharmacist. In addition, although a health professional’s opinion is irreplaceable, the free access to so much different information requires greater training and judgment. In this sense, regarding self-medication, it is “positive to encourage the participation of citizens in everything related to health, but, if the appropriate therapeutic advice is not offered, it can be harmful to the patient” [20] (p. 285). Thus, the key element of responsible behaviour when using medicines also lies in correct information and proper health education.

The importance of such considerations has become more visible worldwide with and after the COVID-19 crisis, which involved a large consumption of pharmaceutical information. “Given the health risk perceived by the population, people feel an urgent need to know its scope with the greatest precision as well as to be informed of appropriate behaviours to reduce risks” [21] (p. 45).

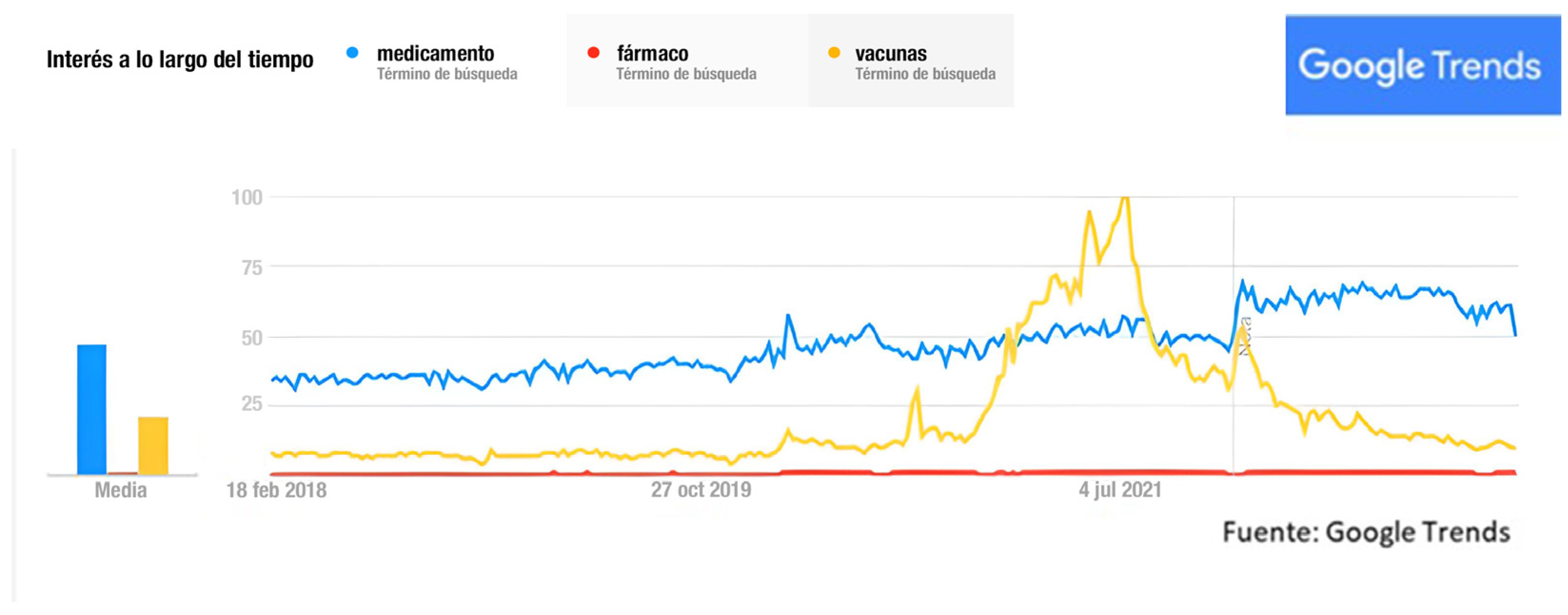

In fact, as can be seen in Figure 1, there was a quantitative leap in the search for the term “vaccine” during the first half of 2021, coinciding with the start of COVID-19 vaccination campaigns around the world, and another peak of this search at the start of the pandemic in March 2020. This behaviour contrasts with that observed in other related words such as the term “medicament”, whose progression has slightly increased but is constant, with some less-relevant peaks.

Figure 1. Searches from February 2018 to May 2022. Source: Google Trends.

Consequently, if a few years ago the advice of a doctor or pharmacist was sufficient for a patient to trust the prescribed treatment, the pandemic accelerated a situation of unprecedented information saturation in the sector, amplified, moreover, by digital media. This situation led to a state of disinformation, or infodemic, whose proper management began to be part of the objectives of the WHO [22]. In the digital environment, it is possible to consult the composition of medicaments, their manufacturing and approval processes and to obtain information from clinical trials on vaccines and other medicaments that are being designed to combat the disease. The pandemic is presented, in this way, as a paradigmatic case study, so it can be expected that it has aroused interest among the scientific community focused on pharmaceutical communication.

References

- Alcalay, R. La Comunicación para la Salud como Disciplina en las Universidades Estadounidenses. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 1999, 5, 192–196. Available online: https://www.scielosp.org/article/rpsp/1999.v5n3/192-196/ (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Bellón, J.A.; Martínez, T. La investigación en comunicación y salud. Una perspectiva nacional e internacional desde el análisis bibliométrico. Atención Primaria 2001, 27, 452–458.

- Cófreces, P.; Ofman, S.; Stefani, D. La comunicación en la relación médico-paciente. Análisis de la literatura científica entre 1990 y 2010. Rev. Comun. Salud 2014, 4, 19–34.

- Juvinyà, D.; Bertran, C.; Suñer, R. Alfabetización para la salud, más que información. Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32, 8–10.

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Carta de Ottawa de Promoción de la Salud. Available online: https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2013/Carta-de-ottawa-para-la-apromocion-de-la-salud-1986-SP.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Juvinyà, D. Alfabetización en salud en la comunidad. Innovación Educ. 2021, 31.

- Mosquera, M. Comunicación en salud: Conceptos, Teorías y Experiencias. Comminit Iniciat. Comun. 2002, 21, 84–107. Available online: https://www.comminit.com/content/comunicaci%C3%B3n-en-salud-conceptos-teor%C3%ADas-y-experiencias (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Martínez-Beleño, C.A.; Sosa, M.S. Aportaciones y Diferencias Entre Comunicación en Salud, Comunicación Para el Desarrollo y Para el Cambio Social. Rev. Comun. Salud RCyS 2016, 6, 69–80. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5786977 (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Evaluate Pharma. World Preview 2022 Outlook to 2028. Available online: https://info.evaluate.com/rs/607-YGS-364/images/2022%20World%20Preview%20Report.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Statista. La Industria Farmacéutica en España—Datos Estadísticos (2022). Available online: https://es.statista.com/temas/5603/la-industria-farmaceutica-en-espana/#topicOverview (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Boletín Oficial del Estado. Real Decreto 1416/1994, de 25 de junio, por el que se Regula la Publicidad de los Medicamentos de uso Humano. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/1994/06/25/1416/con (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Papí, N.; Cambronero, B.; Ruiz, M.T. El género como “nicho”. El caso de la publicidad farmacéutica. Feminismo/s 2007, 10, 93–110.

- Viña, G.; Debesa, F. La Industria Farmacéutica y la Promoción de los Medicamentos. Una Reflexión Necesaria. Rev. Gac. Méd. Espirit. 2017, 19, 17. Available online: http://revgmespirituana.sld.cu/index.php/gme/article/view/1585/html (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Código de Ética y Conducta Profesional. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ethics/code_of_ethics_full_version-es.pdf?sfvrsn=2393d888_14&download=true (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Vacca, C.; Vargas, C.; Cañás, M.; Reveiz, L. Publicidad y Promoción de Medicamentos: Regulaciones y Grado de Acatamiento en Cinco Países de América Latina. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2011, 29, 76–83. Available online: http://www.scielosp.org/pdf/rpsp/v29n2/a02v29n2.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2023).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Marco estratégico de la OMS para las Comunicaciones Eficaces. Available online: Bit.ly/4359qPx (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Grunig, J.; Hunt, T. Dirección de las Relaciones Públicas; Gestión: San Sebastián, Spain, 2000.

- Ibáñez, A.; Carretón, C.; Papí, N. Las relaciones entre agentes implicados durante el desabastecimiento de mascarillas. In La Confianza para la Gestión de Issues en Situaciones de Conflicto; Paricio, M.P., Hernández, S., Eds.; Tirant Humanidades: Valencia, Spain, 2022; pp. 27–44. ISBN 978-84-19226-49-5.

- Álvarez-Cordero, R. Las redes sociales en la educación médica y en la promoción de la salud. Gac. Médica México 2019, 155, 573–575.

- Ras, E.; Moya, P. Prescripción médica o automedicación. Atención Primaria 2005, 36, 285.

- Castro, A.; Torres, J.L.; Carballeda, M.R.; Aguilera, M.D. Comunicación, salud y COVID-19. Cómo comunican los instagrammers sanitarios españoles. Ámbitos Rev. Int. Comun. 2021, 53, 42–62.

- Diario El País. Desinformación Frente a Medicina: Hagamos Frente a la ‘Infodemia’. Available online: https://elpais.com/sociedad/2020/02/18/actualidad/1582053544_191857.html (accessed on 3 April 2023).

More