Breastfeeding is the best and most natural nutrition for infants. Through breastfeeding, infants are offered all the necessary nutrients and elements for their optimal growth and development. The World Health Organization, Unicef, and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life and continuation of breastfeeding (after introduction of solid foods at 6 months) until the first year of life and for as long as the mother and child desire

[1][2][3][1,2,3]. There is indisputable evidence in the literature regarding breastfeeding benefits for the infant, the mother, the family, and the society, in general

[4]. Maternal milk contains the ideal qualitative and quantitative composition for optimal neonatal growth. Breastfeeding contributes to the smooth physical and psychological development of the infant, conferring short-term as well as long-term benefits. First of all, breastfed infants have a decreased risk of childhood mortality

[5][6][7][5,6,7]. Research has revealed that infants who have been breastfed for less than two months and those who are partially or not breastfed have a higher mortality risk compared to exclusively breastfed infants

[8][9][8,9]. Breastfeeding for more than six months protects against obesity, diabetes, asthma, cardiac conditions, and increases final height

[10][11][12][13][14][10,11,12,13,14]. Rich-Edwards et al.

[14] investigated the association between breastfeeding and cardiac conditions and suggested that breastfed infants may present a lower risk of ischemic cardiovascular disease in adulthood. Additionally, breastfed children seem to have lower risk of developing certain types of childhood cancer, including leukemia and lymphomas

[15][16][15,16]. Breastfeeding positively impacts cognitive, emotional, and social development of the infant

[17][18][17,18]. Neonatal mortality and morbidity is reduced in breastfed neonates, in particular preterm newborns. Breastfeeding fortifies the immune system, promoting immune maturation and protecting infants against infections. Breastmilk interacts with gut microbiota and, to a degree, shapes microbiome colonization, with possible effects on long-term programming

[19][20][19,20].

Breastfeeding contributes to the regular physical and psychological development of the infant, with short-term and long-term advantages. The majority of mothers are able to breastfeed and entitled to it, providing they are offered accurate information and are supported by family, healthcare system, and society.

2. Autoimmune Diseases and Breastfeeding

Advantages of breastfeeding in mothers with autoimmune diseases are outlined in the literature. The high prevalence of autoimmune conditions among women indicates the crucial role of gender and hormonal implication in the pathogenesis of these diseases. Evidence suggests a relationship between prolactin and autoimmune diseases, in particular systematic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM)

[28][29][30][31][32][33][28,29,30,31,32,33]. Prolactin is mainly produced in the pituitary gland and its role is not only to stimulate the growth of the mammary gland and the production of milk during lactation, but also to modify the maternal behavior. Genes coding for prolactin are located in chromosome 6, close to HLA-DRB1. Polymorphisms of the human prolactin gene may affect the pathogenesis of autoimmune conditions

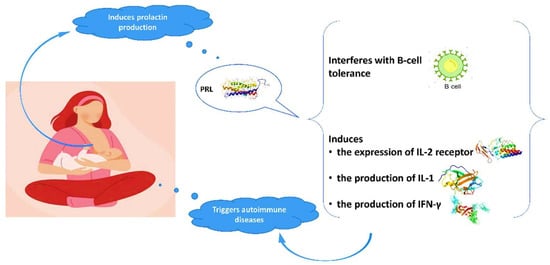

[29][34][29,34]. Elevated prolactin levels may interfere with B-cell tolerance through various mechanisms

[28][35][28,35], while prolactin induces the expression of IL-2 receptor and the production of IFN-γ and IL-1 (

Figure 1). It modifies the maturation of dendritic and thymus cells, leading to IFN-α production and enhancement of pro-B-cells generation.

Figure 1.

Interaction of prolactin with autoimmune system.

2.1. Systematic Lupus Erythematosus and Breastfeeding

Systematic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, multisystemic, inflammatory disease of autoimmune etiology, commonly presented in young women of reproductive age. Prolactin has been found to be implicated in the pathogenesis of antiphospholipid syndrome and the observed impaired fertility

[36][37][38][36,37,38]. Recently, Song et al.

[31], in a meta-analysis, revealed a significantly positive correlation between prolactin and SLE activity. In a large, cohort study by Orbach et al.

[39], SLE patients with hyperprolactinemia presented with significantly more episodes of pleuritis, pericarditis, and peritonitis, and had more frequently anemia and proteinuria compared to patients with normal prolactin levels. The authors concluded that dopamine agonists could be a potential treatment for SLE patients with hyperprolactinemia. In other studies, treatment with bromocriptine has reduced disease activity, and therapy cessation was associated with SLE flares

[36][37][36,37]. Current evidence supports the benefits of treatment with bromocriptine in refractory SLE or in the prevention of flares after labor

[37]. Conclusively, these findings question whether mothers with SLE should breastfeed.

Contrary to the numerous prospective and retrospective studies published on pregnancy outcomes of women with SLE

[40][41][40,41], data regarding breastfeeding are currently scarce. Breastfeeding rates and duration seem to be decreased in SLE patients. Orefice et al.

[42] in a cohort study reported that the vast majority of mothers with SLE (96.5%) were planning to breastfeed during pregnancy and 71.9% did breastfeed. However, half of these patients ceased breastfeeding after 3 months. Additionally, factors including cesarean section, preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and disease flares were positively correlated with non-breastfeeding. Also, a relationship between treatment with hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and delayed breastfeeding cessation was reported for the first time. In subsequent studies, HCQ has shown reduction in disease relapse risk during and after pregnancy

[43][44][43,44], decreased rates of recurrent neonatal lupus and improvement of labor outcome

[45][46][45,46]. In another study, Noviani et al. reported that 49% of participating SLE patients decided to breastfeed

[47]. This rate was not significantly affected by socioeconomic factors. Furthermore, disease activity after labor, full-term labor, breastfeeding education and planning were positively correlated with breastfeeding. Transfer of HCQ, azathioprine, methotrexate, and prednisone to maternal milk seems very limited and all drugs are compatible with breastfeeding

[47]. Acevedo et al.

[48] recorded reduced breastfeeding rates and duration in SLE patients: they breastfed their children half of the time that the mothers without SLE did (6 months vs. 12 months, respectively). The initiation of a new treatment was the main reason for breastfeeding cessation in spite of the fact that these drugs were low risk for breastfeeding. Breastfeeding duration could be improved by enhancing the level of information provided to patients. Complications during the postnatal period were mainly responsible for not initiation of breastfeeding. HCQ is compatible with breastfeeding according to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and most SLE specialists recommend continuation of breastfeeding in SLE patients receiving antimalarial medicines

[49][50][49,50]. Prednisone and ibuprofen in low doses are also acceptable options during pregnancy, while data on the use of other medicines for the treatment of SLE in pregnancy and lactation are limited. Current recommendations advocate for the initiation of HCQ when pregnancy is scheduled and the continuation of the drug throughout pregnancy and lactation

[51].

2.2. Rheumatoid Arthritis and Breastfeeding

High prolactin levels may result either in autoimmune disease presentation in mothers with predisposition or in flares in patients with existing conditions

[52]. Risk for RA onset increases during the postpartum period, particularly after the first pregnancy

[53]. Women who developed RA within 12 months of the first pregnancy were five times more likely to have breastfed, while breastfeeding rates sharply declined in a subsequent pregnancy

[54]. Barrett et al.

[55] compared disease activity during and for 6 months after pregnancy between 49 patients who did not breastfeed, 38 who breastfed for the first time and 50 who had previous breastfeeding experience. Following adjustment for possible confounding factor, including treatment, patients who were breastfeeding for the first time showed increased disease activity 6 months after labor, indicated by self-reported symptoms, number of affected joints, and C-reactive protein levels, suggesting that this flare could be caused by breastfeeding. Brennan and Silman

[54] investigated whether the presentation of RA after labor could be attributed to breastfeeding. Through a media campaign, the authors interviewed 187 women who presented RA within 12 months of labor and compared their breastfeeding history with that of 149 women of similar age selected from the patient registers of a nationwide group of general practitioners. In total, 88 women developed RA after their first pregnancy, and 80% of them breastfed. This rate was higher than the prevalence of breastfeeding (50%) in the 129 controls (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 5.4, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 2.5–11.4). The risk for RA development was less increased following breastfeeding in a second (OR 2.0) and not increased in a third pregnancy (OR 0.6). More recently, Eudy et al.

[56] in a cross-sectional study reported that most women with RA breastfed and were regularly receiving treatment during lactation. Disease activity seemed to worsen, in particular for the patients who did not receive treatment during lactation, while improvement was only observed in women who followed treatment during breastfeeding. Ince-Askan et al.

[57] in a prospective cohort study concluded that only 4% of mothers with arthritis exclusively breastfed until 26 weeks compared to 25% of the general population.

2.3. Idiopathic Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Breastfeeding

Idiopathic inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) are chronic intestinal disorders usually diagnosed during the second and third decades of life. The effect of pregnancy on the course of disease varies; the majority of patients remain in remission, while a few of them improve probably due to generalized immunosuppression during gestation. Contrarily, 1/3 of patients deteriorate

[58][59][58,59]. Although the exact mechanisms explaining aggravation in pregnancy are not known, it is speculated that the cause may be the lack of maternal- fetal immunocompatibility

[60]. Consequently, women with IBD may present with disease activation and need treatment at conception, pregnancy, or labor. Women with IBD are at increased risk for spontaneous abortions, preterm labor, and low birth weight neonates

[59][61][59,61]. Some researchers suggest an increased risk of chromosomal disorders (although the role of disease activity relative to that of the drug exposures has not been elucidated) and adverse perinatal outcomes in patients with IBD

[59][62][59,62]. Breastfeeding rates in women with IBD range among studies. Dotan et al.

[62] reported that mothers with IBD breastfed less frequently. Approximately 1/3 of them did not breastfeed at all compared to 1/5 of healthy controls (

p < 0.005), and short-term and long-term breastfeeding were also less common in mothers with IBD. Moreover, mothers who received treatment with immunomodulators and steroids had significantly lower breastfeeding rates in comparison to women who were only administered 5-ASA. In a study by Moffatt et al.

[63], 83.3% of IBD patients began to breastfeed compared to 77.1% of the general population (

p > 0.05). With regards to breastfeeding duration, 56.1% of IBD patients vs. 44.4% of the general population breastfed for more than 24 weeks (

p = 0.02)

[63]. The rate of disease flare during the first year after labor was 26% for breastfeeding and 29.4% for non-breastfeeding patients with Chron’s disease (CD,

p = 0.76) and 29.2% for breastfeeding vs. 44.4% (

p = 0.44) for non-breastfeeding women with ulcerative colitis (UC). The risk for disease flare was independent of age, disease length, and socio-economic status. The authors concluded that IBD does not seem to reduce chances of breastfeeding. Lactation is not associated with increased risk of flares; contrarily, it could be protective during the first year after labor. Kane et al.

[64] studied 122 women with IBD who were asymptomatic during pregnancy. Only 44% breastfed due to doctor recommendations, fear of drug interactions, and personal choice. Of those who breastfed, 43% presented postpartum disease flare. Non-adjusted OR for disease activity in women with breastfeeding history was 2.2 (95% CI 1.2–3.9,

p = 0.004). After risk stratification by disease type, OR for UC was 0.89 (95% CI 0.29–2.7,

p > 0.05), and for CD it was 3.8 (95% CI 1.9–7.4,

p < 0.05). Following adjustment for treatment cessation, statistical significance of OR was not retained. These results indicate that a significant number of IBD patients do not breastfeed. A relationship between breastfeeding and disease activity may be owing to IBD treatment cessation.

Breastfeeding has been associated with prevention of IBD in children

[62][65][66][62,65,66], a benefit which should be taken into serious consideration by mothers with IBD.

2.4. Multiple Sclerosis and Breastfeeding

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune inflammatory disease in which sclerotic plaques are formed in the central nervous system causing neuronal demyelination and damage. MS is usually encountered in women of childbearing age

[67], and although disease modifying treatments (DMTs) reduce relapse rates, none of these treatments are recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding

[68][69][70][68,69,70].

MS relapse rates are decreased during the last trimester of pregnancy, but they rise during the first 3 months after labor, with up to 30% of patients relapsing

[71]. Postpartum relapses are associated with high risk of disability

[71] and deterioration of existing disability

[72]. Women are frequently faced with the dilemma of breastfeeding or not breastfeeding and re-initiating DMT after labor. Despite the many observational studies, there is no consensus to date as to whether there is a relationship between breastfeeding and postpartum relapse control

[72][73][74][75][72,73,74,75]. In 2012, a meta-analysis showed that non-breastfeeding women had double the risk of postpartum relapse than breastfeeding mothers

[76]. However, there is great heterogeneity among studies included in this meta-analysis, and researchers did not assess whether disease activity before pregnancy affected the findings of the study or if the results were attributed to exclusive breastfeeding and its different hormonal impact from non-exclusive breastfeeding. Krysko et al.

[70], in a 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis, demonstrated that breastfeeding was correlated with lower rate of postpartum MS relapses, with this beneficial effect being greater in cases of increased disease activity and exclusive breastfeeding. For a mother with MS, and possibly mobility problems, breastfeeding advantages may help improve her quality of life and health.