A plant-based diet refers to a way of eating that primarily focuses on consuming foods derived from plants. This includes a wide variety of vegetables, fruits, beans, lentils, legumes, nuts, seeds, fungi, and whole grains. Animal products and processed foods are limited or avoided in this dietary approach.

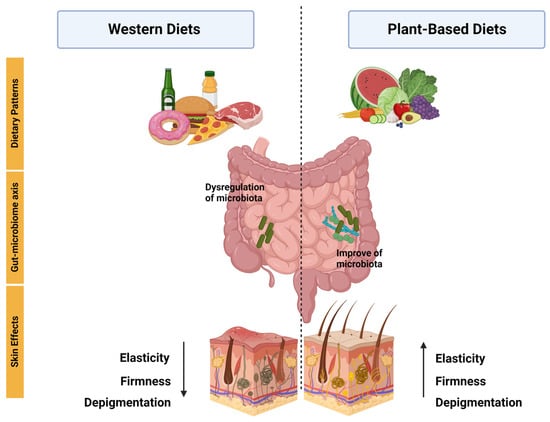

Plant-based diets have been found to have benefits for various conditions and diseases and specific plant-based functional foods can play a role in supporting skin health. One of the targets of this dietary pattern is the gut microbiota, the community of microorganisms residing in our digestive system. Improving the health of the gut microbiota may contribute to some of the positive effects observed on overall health, including the skin.

By adopting a plant-based diet, individuals can provide their bodies with a rich array of nutrients, antioxidants, and fiber that are abundant in plant foods. These components can support overall health and may have a positive impact on the condition of the skin. However, it's important to note that individual results may vary, and maintaining a balanced diet, as well as considering other factors like skincare routines and overall lifestyle, is essential for optimal skin health.

- diet

- skin health

- inflammatory skin diseases

- plant-based diet

- plant-based diet functional-foods

1. Introduction

2. Association between Plant-Based Diet and Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic immune-mediated skin disease that affects approximately 3% of the population. It is characterized by scaly, red patches on the skin with well-defined borders [14][15]. Psoriasis is not only a skin condition but can also affect multiple organs, leading to persistent inflammation and a significant decrease in quality of life [16]. The underlying cause involves dysregulation of the immune response and abnormal skin cell growth, resulting in increased levels of inflammatory substances like interleukins and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [17][18]. Various environmental factors, including stress, smoking, and diet, play a role in the development and progression of psoriasis. In particular, there is a strong association between psoriasis and poor diet-related conditions such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease [19]. Patients with psoriasis often seek complementary or alternative therapies to improve their symptoms, overall health, and quality of life [20]. Different diets have shown benefits for psoriasis. A study conducted with a group of psoriasis patients investigated their dietary habits and compared the effects of various diets, including plant-based (vegan, Pagano, and Paleolithic diets), gluten-free, Mediterranean, vegetarian, and carbohydrate-high protein diets [21]. The study found that dairy and sugar consumption were commonly reported as triggers for psoriasis. Additionally, adding vegetables to the regular diet alone showed a positive skin response in 42.5% of patients, while probiotics, organic foods, and fruits had favorable effects in 40.6%, 38.4%, and 34.6% of patients, respectively. Meat and eggs were identified as less common triggers [21]. Avoiding certain foods such as junk foods, white flour products, dairy, pork, and red meat also demonstrated beneficial effects. Moreover, more than half of the patients (69%) who followed any of these diets reported significant weight loss, indicating a connection between plant-based diets and a reduction in body mass index (BMI) [21]. Being overweight or obese is a well-established risk factor for the development of psoriasis and is also associated with more severe stages of the disease [22]. Research suggests that targeting body mass index (BMI) in patients who have not responded well to conventional systemic therapies, including etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, ciclosporin, and PUVA (8-MOP) psoralen combined with ultraviolet A therapy, may be beneficial [23]. The connection between obesity and psoriasis stems from the fact that adipose tissue in obese individuals can produce excessive amounts of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-8, IL-6, and TNF, which contribute to the development of psoriasis [22]. Plant-based diets that aid in reducing BMI and promoting weight loss may have a positive impact on psoriasis symptoms. Therefore, incorporating these diets into the management of psoriasis could be considered an important approach. In one case study psoriatic arthritis, a patient reported significant improvement in symptoms such as scalp issues, joint pain, stiffness, and uveitis after adopting a whole-food plant-based diet [24]. By avoiding animal-derived foods like dairy and red meat, she experienced positive changes and eventually transitioned to a strictly vegan diet. This dietary shift allowed her to reduce her medication dosage compared to a previously implemented gluten-free diet with no clinical improvement. Blood test results also showed positive markers of reduced inflammation after approximately 6 months on the plant-based diet [24]. However, more studies are needed to fully evaluate the potential elimination of medication for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. In another case study, a male patient with severe plaque psoriasis achieved remission after undergoing a medically supervised water-only fast followed by adopting a plant-based diet[25].The patient experienced improvements in the severity of psoriasis plaques, nailbed psoriasis pain, arthritis, and significant weight loss, resulting in a healthy body mass index. Following the treatment, the patient maintained a whole-plant diet without salt, sugar, and oil, reporting no new lesions and continued improvement in existing plaques [25].A plant-based diet that limits or excludes animal-derived products while increasing the intake of vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, and cereals has shown benefits for skin health [7]. This type of diet is low in saturated fat, trans fat, and arachidonic acid while being rich in antioxidants and omega-3 fatty acids. These properties, along with the diet's anti-inflammatory effects and ability to promote weight loss, contribute to improved overall well-being for psoriatic patients. Therefore, incorporating plant-based diets as a potential therapeutic option is recommended for the management of certain psoriatic patients.

3. Association between Plant-Based Diet and Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common inflammatory skin disease characterized by redness, itchy bumps, and scaly patches, primarily found in areas like the hands, neck, and head [26]. It is influenced by various factors, including genetics, the environment, and immune activity. The development of AD involves the infiltration of eosinophils and T-lymphocytes, skin barrier dysfunction, changes in the skin's microbiota, abnormal immune responses, and sensitization to immunoglobulin E (IgE) [27]. The standard treatment for AD includes corticosteroids (applied topically or taken systemically), emollients, anti-inflammatory drugs, antihistamines, and immunosuppressive drugs like cyclosporine-A [28]. There is a known association between AD and food allergies, so avoiding certain foods has shown therapeutic benefits [29].

Two studies provide evidence regarding the impact of diet on atopic dermatitis (AD). In an open-trial study, a vegetarian diet was found to significantly reduce the severity of AD symptoms, as measured by the SCORAD index, which assesses erythema, edema, crusts, and excoriation. This improvement in skin inflammation was accompanied by a decrease in LDH5 activity, the number of eosinophils and neutrophils in the blood, and the synthesis of PGE2, an inflammatory mediator. The study also observed a decrease in serum IgE levels and a return to normal levels of peripheral eosinophils [30].

The intervention involved a vegetarian and low-energy diet with a daily calorie intake of 1085 kcal. The diet included fresh vegetable juice, brown rice with kelp powder, tofu, and sesame paste, administered over a period of 2 months. No adverse effects related to the vegetarian diet were reported [31]. However, further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to fully understand the anti-inflammatory effects of plant-based diets in AD.

One of the main concerns associated with vegetarian and plant-based diets is the possibility of nutritional deficiencies. However, in the mentioned study, no serious adverse events were reported, indicating that the vegetarian and low-energy diets were well-tolerated. These diets may have benefits for individuals with AD, as they provide antioxidants like vitamins C and E, which can help reduce skin inflammation. Additionally, the potential reduction in body mass index (BMI) associated with these diets may contribute to improved skin health [31].

4. Association between Plant-Based Diet and Acne

Acne vulgaris is the most common form of acne that affects the hair follicles and oil glands. It is characterized by different types of skin blemishes like blackheads, whiteheads, pimples, nodules, and cysts. Acne is prevalent worldwide, with approximately 9.4% of the population affected, and it is most commonly seen in adolescents, with around 85% of cases occurring in this age group. Several factors contribute to the development of acne. Excessive production of sebum (oil) by the skin, the overgrowth of bacteria called Cutibacterium acnes, and the accumulation of dead skin cells within the hair follicles are recognized as key mechanisms. Inflammation also plays a role in acne formation. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is believed to be an important factor in the progression and severity of acne. It stimulates the overproduction of sebum and promotes the proliferation of sebocytes (oil gland cells) and keratinocytes (cells lining the hair follicles) [32][33][34]. Acne is influenced by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, including hormones and diet. For example, when certain populations adopt a Western-style diet, it can lead to the development of acne. However, the exact relationship between acne and diet is still being studied and understood by researchers [35][36][37]. In a case-control study, an increased risk of developing moderate to severe acne was reported with the regular consumption of low fat, and whole milk and the intake of eggs had similar results. Also, it was found that the association between the consumption of vegetables and low BMI [38]. The association found between milk intake and acne may be due to certain amino acids that stimulate the synthesis of IGF-1. On the other hand, egg contains leucine, that through the synthesis of lipids and proteins increases the activity of sebaceous glands [38]. This suggest that a well design plant-based diet may be helpful in adolescents wit acne. Research conducted on young adults has shown that individuals with acne tend to have a higher intake of certain foods compared to those without acne. Specifically, acne patients were found to consume more meat, beef, fish, butter, honey, corn, rice, chicken, and pizza compared to the control group. On the other hand, the control group had a higher consumption of vegetables and potatoes. Interestingly, among acne patients, those with mild acne tended to consume a greater amount of vegetables compared to those with more severe acne. Furthermore, a vegetarian diet was observed in more than half of the controls, while in patients with acne, it barely exceeded 10% [39]. These findings suggest a potential link between dietary choices and acne development, although further research is needed to fully understand the relationship.5. The Role of Plant-Based Functional Foods on Skin Health

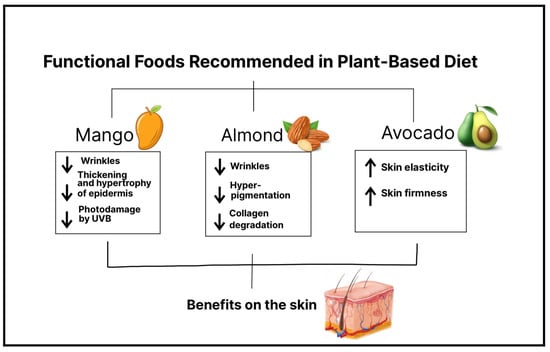

Continuous exposure to UV radiation affects skin health leading to the breakdown of collagen and a reduction in elastin fibers within the dermis, resulting in the formation of wrinkles, loss of skin elasticity, and pigmentation issues a process called photoaging [40]. Recently it has been found that functional food benefit skin health. In accordance with the International Life Sciences Institute, “functional foods” are foods that provide health benefits beyond basic nutrition, due to the effectiveness of their active substances [11]. Therefore, in a plant-based diet, a wide variety of plant-based functional foods can be found, and if they are consumed regularly and in a proper amount, it is possible to observe their beneficial effects on the skin [41] (Figure 1).

5.1. Mango

Mangos are a rich source of vitamin C, B-carotene, xanthones such as mangiferin, and phenolic acids, the main ones being gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, protocatechuic acid, and vanillic acid [42]. Moreover, vitamin C is a known antioxidant, and it is found in high concentrations in skin cells in the human body. Among the properties of vitamin C or ascorbic acid is its ability to stimulate collagen and elastin synthesis, protect against oxidative stress, and reduce damage caused by UV-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS), thus preventing photoaging. B-carotene is a precursor of vitamin A, both of which can provide photoprotection and prevent photodamage due to increased epidermal proliferation [43]. In addition, certain types of mangos, specifically Ataulfo mango, contain more than the daily diet requirement of vitamin C [44]. Regarding the protective properties of mango on the skin, a study reported that mango extract obtained from dried mango reduces the formation of wrinkles induced by UVB radiation, improves wrinkles, inhibits the loss of collagen fibers, and decreases the thickening of the epidermis, as well as its hypertrophy. Therefore, the results confirm a clear photoprotective and antiaging activity of mango, in which mangiferin seems to play a key role. This study was carried out in mice, and the mango intervention was performed by oral administration. This evidence leaves a foundation for future mango intake interventions in humans [40]. A clinical trial (n= 28) examined the effects of Ataulfo mango consumption on facial photodamage. Consuming 0.5 cups of frozen Ataulfo mango over 8 to 16 weeks reduced facial wrinkle depth and severity. Serum triglyceride levels also decreased compared to baseline. However, consuming higher amounts of mango (1.5 cups) increased facial wrinkles. Mango's beneficial effects are attributed to compounds like mangiferin, carotenoids, and flavonoids. On the other hand, higher mango intake may lead to collagen fiber glycation and structural disruption due to increased sugar intake. Blood glucose levels did not significantly change [44]. These findings emphasize the importance of consuming adequate amounts of mango and avoiding overconsumption, which can worsen skin conditions. Although evidence is limited, mango's antioxidant properties and recent developments support its inclusion in a balanced diet. Furthermore, in another study, it has been shown that the antioxidant properties and bioavailability of mango phenolic acids are preserved whether the pulp is ingested or processed into juice, with the juice presentation being the one in which their properties may be enhanced [45]. This evidence suggests that people can consume mango in various presentations without concerns about diminishing its properties.5.2. Almond

Almonds are a rich source in alpha tocopherol (vitamin E), fatty acids, and polyphenols, making them a valuable source of antioxidants [46]. A study conducted by Negar et al. investigated the effects of almond consumption on the severity, depth, and length of facial wrinkles, and the results revealed a significant improvement in wrinkle appearance. In this controlled trial involving 31 participants, women consumed 2.1 oz (340 kcal) of packaged almonds over a 16-week period. Notably, no increase in sebum production or other adverse effects related to almond intake were reported [47]. Another study proved that daily consumption of almonds significantly decreased average wrinkle severity and the intensity of facial pigmentation without an increase in sebum production in the face in 56 postmenopausal women [48]. The beneficial effects of alpha tocopherol against skin aging could be due to vitamin E consumed through almond intake which has antioxidant and photoprotective properties and thus a protective effect against free radicals and the damage they cause since vitamin E is incorporated into the cell membrane. Vitamin E can also potentially prevent collagen degradation, thanks to a decrease in the activity of matrix metalloproteinases. Therefore, an adequate daily intake of almonds can be a potential alternative to prevent or decrease the progression of wrinkles and facial pigmentation and thus skin aging.5.3. Avocado

Recent studies have provided evidence that avocados have beneficial properties due to the food’s compounds: carotenoids, monounsaturated fatty acids, and phenols. The well-known beneficial properties of avocado on the skin, such as increased skin elasticity, include its topical application as a cream, but it has recently been demonstrated that oral intake of avocado also has skincare effects [49]. For instance, Henning et al., in a pilot study (n= 39), reported significant changes in facial skin in overweight women who added the consumption of an avocado to their daily diet. The results were an improvement in skin elasticity and skin firmness in the forehead and under-eye location. There were no adverse effects related to avocado intake such as weight gain or increased production of facial sebum. This improved skin status might be a result of a mechanism in which the expression of certain genes, such as collagen and elastin genes, is induced after making dietary modifications [50]. Thus, the evidence found suggests that the addition of avocados to the daily diet has a potential positive impact on improving and maintaining the elasticity and firmness of the skin, or delaying aging.6. Association between Plant-Based Diet Alternatives and Gut Microbiome

The effects of different types of diets on the skin have gained great interest in the last decades. However, it is difficult to evaluate the impact that diets have directly on the skin because they also have significant effects on the gut microbiome, which can also influence skin health [51]. Indeed, extensive evidence has demonstrated a bidirectional interaction between the intestine and the skin either to maintain their homeostasis or to alter their biology [52]. For instance, animal models of patients with common skin disorders such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, as well as other less common conditions such as rosacea, show distinct gut microbial profiles [53]. The gut microbiome is the largest endocrine organ, located between food intake and various body organs such as the skin. It produces several metabolites including short-chained fatty acids (SCFA), neurotransmitters, tryptophan derivatives, and bile acids, among others. These metabolites influence gut physiology, including gut barrier integrity, and can also reach distant organs generating pleiotropic effects [54]. Interestingly, skin health has been associated with the integrity of the intestinal barrier [55]. Moreover, some bacterial metabolites show immuno-modulating potential on distant organ sites such as the skin which is currently a growing field of research. While some dietary metabolites can be absorbed directly into the skin [56][57], others do so via gut microbial metabolism, both of which can potentially contribute to skin health and various skin disorders and diseases [58][59]. Among numerous other factors, diet strongly influences the composition of the gut microbiome and, in this way, the organism’s metabolic and immunological functions [51]. Changes in macronutrients, as well as their source (plant or animal), may particularly affect the diversity of the gut microbiome [60]. In addition, the amount and source of dietary fiber can have a major impact on the composition and diversity of the human gut microbiota [61]. To illustrate, the consumption of whole grains or cereal fibers can induce a higher abundance of Bifidobacterium, which is decreased in distinct pathologies, including atopic dermatitis [62][63]. The importance of the host dietary patterns on the gut microbiota has also been demonstrated in studies that observe a greater bacterial diversity, as well as a greater abundance of potentially beneficial bacteria, with a high-quality diet or a diet rich in “healthy foods” [64][65][66]. Other studies show that Mediterranean or vegetarian/vegan diets, enriched in plants (an important source of natural fiber) and omega-3 fatty acids and low in saturated fat and animal protein induces an increase in dietary-fiber-metabolizing bacteria that produce SCFA [67]. In contrast, the consumption of a high-fat diet induces alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota, termed dysbiosis, that by increasing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines promotes higher intestinal permeability [68]. Decades ago, studies reported an association between the consumption of Western diets and a variety of skin diseases such as acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis [69][70][71]. Thus, it has been described that the infiltration of molecules, derived from an increased intestinal permeability, further introduces proinflammatory mediators into the circulation which can lead to the disruption of skin homeostasis and thus contribute to the physiopathology of these diseases [68]. Moreover, bacterial metabolism derived from the consumption of Western-type diets can result in the production of harmful metabolites, such as p-cresol, that are also associated with impaired epidermal barrier function [53]. Remarkably, in the consumption of plant-based diets, microbial metabolism release and transform phytochemicals with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant functions [72]. Moreover, the production of SCFA associated with the consumption of the Mediterranean diet (also rich in plants) can have favorable effects on gut barrier integrity [73]. SCFA, particularly butyrate, are also able to improve the skin barrier and relieve skin inflammation [74]. In fact, low levels of fecal SCFA have been observed in patients with eczema and atopic dermatitis, and interventions with SCFA-producing probiotics are able to ameliorate inflammation in other skin conditions [75]. Overall, the latter evidence underscores the importance of the diet–gut–skin axis. In fact, it has been proposed that skin inflammation is also a consequence of changes in the intestinal microbiome caused by specific diets [76]. For example, in dermatitis herpetiformis, a cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease, patients can palliate their skin rashes when consuming a gluten-free diet [77]. Research has suggested that plant-based functional foods may have a beneficial impact on inflammatory diseases, specifically by improving skin health. This improvement has been linked to the interaction between the intestinal microbiota and a diverse range of bacteria that are specific to these skin diseases, including psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and acne (Figure 2).

| Study Design | Participant Characteristics | Intervention Details | Outcomes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exploratory survey study | 1206 psoriasis patients. The mean age of the sample population was 50.4, and 73% of respondents were female. | The survey contained 61 questions; the first 30 questions were from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; the last 31 questions focused on patient-report skin responses to dietary changes. | 72% of Pagano, 70% of vegan, and 68.9% of Paleolithic diets reported favorable skin response. The addition of fruits to the diet was protective against psoriasis, OR 0.22, p < 0.0001. | [21] |

| Assessor-blind, randomized controlled trial | 303 patients between 18 and 80 years, overweight or obese, with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. | Each participant underwent an introductory session with a dietitian. Subjects were instructed to perform sessions of continuous aerobic physical exercise for at least 40 min three times a week. Compared how psoriasis severity was affected by either a 20-week quantitative or qualitative dietary plan associated with physical exercise for weight loss. | Reduction of PASI score by 48% in the dietary intervention and 25.5% in the information-only. | [23] |

| Cross-sectional study | 56,896 participants. The mean age was 55.8, and 22,577 were female. | First, the researchers sent out a digital questionnaire focused on atopic dermatitis (AD). After collecting the responses, they administered another questionnaire to extract data on lifestyle factors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, stress, obesity, physical activity, and diet (participants were dichotomized into vegetarian/vegan and nonvegetarian/nonvegan), and finally analyzed the association between lifestyle factors and presence of AD. | No associations were observed with abdominal obesity, physical activity, diet quality, or a vegetarian/vegan diet. | [81] |

| Controlled clinical trial | 19 patients with atopic dermatitis. The mean age was 25.5. | The patients were exposed to a low-energy diet, no pharmacotherapy. The SCORAD indices were noted by 2 dermatologists. Blood and urine samples were collected at weeks 0.4 and 8. The 24 h void urine was collected and kept frozen at −80 °C. | SCORAD significant reduction from 6.1 ± 2.8 at week 0 to 2.7 ± 2.8 at week 8. | [31] |

| Clinical trials | Twenty patients (6 males and 14 females) aged 15 to 36 years (average: 25 years) with AD varying in severity from mild to serious. All patients fulfilled the criteria for atopic dermatitis (AD) established by Hanifin and Rajka. |

All patients followed the same meal plan throughout the study. The diet included a glass of fresh vegetable juice for breakfast, followed by brown rice porridge, kelp powder, tofu, and sesame paste for both lunch and dinner. In addition, a daily intake of 2.5 g of non-refined salt was included in the diet. Instead of regular water, the patients were provided with persimmon leaf tea. This treatment regimen was followed for two months. | Reduction in SCORAD index from 49.9 ± 18.6 to 27.4 ± 16.8 (p = 0.001), diminution in peripheral eosinophil count 423 ± 367 to 213 ± 267 (p = 0.01), reduction in monocyte PGE2 synthesis 2886 ± 1443 to 1390 ± 773 (p = 0.001). | [30] |

| Case-control cross-sectional questionnaire study | 57 acne vulgaris patients as cases and 57 participants as controls. Aged 14 and above and were seeking medical consultations at a private clinic. | The Comprehensive Acne Severity Scale (CASS) grading system was used to grade acne severity. Cases were defined as patients with CASS grade of two to five and controls with CASS grade 0 or 1. Thereafter, controls were recruited and matched by age, gender, and ethnicity. A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect information regarding the participants’ dietary intake and cigarette smoking habits. | No significant associations were found between dietary patterns and acne; on the other hand, they only found an association between milk and chocolate consumption and acne. | [35] |

| Case-control study | 279 acne patients and 279 controls aged 10–24 years. | Acne severity was determined by a dermatologist using the Global Acne Severity Scale. Epidemiological data were collected with a pre-structured questionnaire. The food consumption habits were recorded using a food frequency questionnaire. Investigated food included whole milk, low-fat milk, cream of milk, ice cream, cheese, chocolate, cake, potatoes, fresh fruit, fresh vegetable, meat, chicken, and egg. Consumption habit data were collected for 8 months. | The study found that consuming whole milk at least three days a week was significantly associated with moderate to severe acne (OR = 2.36, 95% CI, 1.39–4.01). The association was slightly weaker for low-fat milk (OR 1.95, 95% CI, 1.10–3.45). | [38] |

| A prospective case-control study | 460 subjects of both sexes, 230 patients with acne vulgaris, and 230 healthy volunteers were included as controls. | Acne severity in patients was classified as mild, moderate, and severe according to the classification of the American Academy of Dermatology. Two formulated tools were used in the study. First tool: interview questionnaires that included two parts (sociodemographic data, anthropometric measurements, and questions related to food habits, drug intake, and diet history). Second tool: a recommended diet regimen. | Significantly decreased consumption of vegetables was noticed among severe and moderate acne patients compared with mild ones. | [39] |

| Clinical-trial study | Healthy postmenopausal women aged 50 to 70 (N = 28). Inclusion criteria were Fitzpatrick skin type I, II, or III and a body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 and 35 kg/m2. | Participants were randomized by block design into an open-label, two-arm parallel clinical trial consuming either 85 g or 250 g of Ataulfo mango, four times per week for 16 weeks. | 0.5 cup frozen Ataulfo mango consumption decreases facial wrinkle depth and severity and photodamage induced by UVB. Serum triglycerides decreased. A higher amount of mango (1.5 cups) showed the contrary effect. | [44] |

| Randomized clinical trial | Thirty-one participants (all postmenopausal females) with a Fitzpatrick skin type 1 or 2. | Consisted of a total of five study visits following a 4-week dietary washout period: baseline, 4, 8, and 16 weeks. The patients were randomized into two intervention groups: almond group and control group. Almond group received an average of 340 kcal/day of almonds. | There were no significant differences in sebum production and transepidermal water loss between the almond and control groups. Wrinkle severity and wrinkle width were significantly decreased in the almond group compared with the control intervention. | [47] |

| Randomized- blinded | 56 postmenopausal women with a Fitzpatrick skin type I or II. | A total of 56 female participants were randomly assigned to two intervention groups: the almond group, which received almonds, and the control group, which received a calorie-matched snack. In the almond group, the dose of almonds provided accounted for 20% of the total energy in the participants’ diet. The almond snack group received approximately 2 g of sugars per day, whereas the control snack group received approximately 8 g of sugars per day that was additional to their regular food intake. 24 weeks. | Reduction in the average severity of wrinkles compared to the baseline. Additionally, intensity of facial pigmentation decreased in the almond group. | [48] |

| Randomized parallel group | 39 women with a Fitzpatrick skin type II–IV. | The patients were randomized into two intervention groups: avocado and control. The participants either consumed one avocado daily or no avocado based on randomization performed. 8 weeks. | Daily consumption of one avocado per day for 8 weeks improved firmness and elasticity and reduced the tiring of repeat stretching of the forehead skin. | [50] |

| Case-control | 30 patients with AD (according to the criteria for the diagnosis of AD established by the Japanese Dermatological Association) less than 20 years of age and age- and sex-matched control subjects (68 healthy individuals). | A questionnaire survey was conducted for 1 week, and then fecal specimens and 24 h skin secretion specimens were collected from all subjects. Fecal microflora, fecal IgA levels, and IgA concentrations in the skin were analyzed. The data for the 2 groups (i.e., patients with AD and healthy control subjects) were compared. | The counts of Bifidobacterium were significantly lower in patients with AD than in healthy control subjects (9.75 ± 0.68 vs. 10.10 ± 0.50, p < 0.05). Percentages of Bifidobacterium were significantly lower in patients with severe skin symptoms than in those with mild skin symptoms (40 ± 6% vs. 19 ± 6%, p < 0.05). In addition, the frequency of occurrence of Staphylococcus was significantly higher in patients with AD than in healthy control subjects (83% vs. 59%, p < 0.05). | [80] |

| Case-control | 21 psoriasis patients from a Brazilian referral dermatology service and 24 controls. | A stool sample was collected from each participant at the time of inclusion in the study, and the samples were analyzed by sequencing the 16S rRNA gene. | Patients with psoriasis showed higher levels of the Dialister genus and the species Prevotella copri compared to the control group. Conversely, there was a decrease in the Ruminococcus, Lachnospira, and Blautia genera, as well as the Akkermansia muciniphila species, in the psoriasis group compared to the control group. Additionally, individuals with psoriasis had lower diversity in their gut microbiota compared to the control group. | [79] |

| Case report | 63-year-old woman with ulcerations on both lower legs and diagnosed livedoid vasculopathy by biopsy. | The patient adopted a whole-food plant-based diet (WFPB) as a potential treatment with no other form of treatment. | The symptoms were initially completely resolved, but they reappeared later due to a lack of adherence to a proper diet. | [82] |

| Case report | 58-year-old female patient with pemphigus vulgaris and type 2 diabetes mellitus. | Incorporated a change in lifestyle with different approaches, including hydrotherapy, yoga, a vegetarian diet, herbal preparations, and massage. | The patient was successfully weaned off all medications and had complete remission from PV. | [83] |

| Cross-sectional | They measured skin autofluorescence (SAF) in 332 adult hemodialysis patients who were dialyzing in north central London. | SAF was measured in 332 adult dialysis patients. | SAF was lower in the twenty-seven vegetarians than it was in the non-vegetarians. | [84] |

| Observational retrospective | 21 omnivore patients, 21 vegan patients, with surgical excision of melanoma. | The assessment of postsurgical complications and the quality of scars was conducted using a modified version of the Scar Cosmesis Assessment and Rating (SCAR) scale. | Wound diastasis was more frequent in vegans (p = 0.008). Higher modified SCAR score than omnivores (p < 0.001), worst scar spread (p < 0.001), more frequent atrophic scars (p < 0.001), and worse overall impression (p < 0.001) were observed in vegans. | [29] |

References

- Zhang, S.; Duan, E. Fighting against Skin Aging: The Way from Bench to Bedside. Cell Transplant. 2018, 27, 729–738.

- Dąbrowska, A.K.; Spano, F.; Derler, S.; Adlhart, C.; Spencer, N.D.; Rossi, R.M. The relationship between skin function, barrier properties, and body-dependent factors. Skin. Res. Technol. 2018, 24, 165–174.

- Chambers, E.S.; Vukmanovic-Stejic, M. Skin barrier immunity and ageing. Immunology 2020, 160, 116–125.

- Mohania, D.; Chandel, S.; Kumar, P.; Verma, V.; Digvijay, K.; Tripathi, D.; Choudhury, K.; Mitten, S.K.; Shah, D. Ultraviolet Radiations: Skin Defense-Damage Mechanism. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 996, 71–87.

- Pasparakis, M.; Haase, I.; Nestle, F.O. Mechanisms regulating skin immunity and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 289–301.

- Richmond, J.M.; Harris, J.E. Immunology and skin in health and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a015339.

- Kent, G.; Kehoe, L.; Flynn, A.; Walton, J. Plant-based diets: A review of the definitions and nutritional role in the adult diet. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81, 62–74.

- Fam, V.W.; Charoenwoodhipong, P.; Sivamani, R.K.; Holt, R.R.; Keen, C.L.; Hackman, R.M. Plant-Based Foods for Skin Health: A Narrative Review. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, 614–629.

- Craig, W.J.; Mangels, A.R. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Vegetarian diets. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1266–1282.

- Solway, J.; McBride, M.; Haq, F.; Abdul, W.; Miller, R. Diet and Dermatology: The Role of a Whole-food, Plant-based Diet in Preventing and Reversing Skin Aging—A Review. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2020, 13, 38.

- Temple, N.J. A rational definition for functional foods: A perspective. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 957516.

- Nayak, S.N.; Aravind, B.; Malavalli, S.S.; Sukanth, B.S.; Poornima, R.; Bharati, P.; Hefferon, K.; Kole, C.; Puppala, N. Omics Technologies to Enhance Plant Based Functional Foods: An Overview. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 742095.

- Pinela, J.; Carocho, M.; Dias, M.I.; Caleja, C.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Wild Plant-Based Functional Foods, Drugs, and Nutraceuticals. In Wild Plants, Mushrooms and Nuts: Functional Food Properties and Applications; Wiley Online Library: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 315–351.

- Kamiya, K.; Kishimoto, M.; Sugai, J.; Komine, M.; Ohtsuki, M. Risk Factors for the Development of Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4347.

- Michalek, I.M.; Loring, B.; John, S.M. A systematic review of worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31, 205–212.

- Rendon, A.; Schäkel, K. Psoriasis Pathogenesis and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1475.

- Armstrong, A.W.; Read, C. Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment of Psoriasis: A Review. JAMA 2020, 323, 1945–1960.

- Dowlatshahi, E.A.; Van Der Voort, E.A.M.; Arends, L.R.; Nijsten, T. Markers of systemic inflammation in psoriasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 169, 266–282.

- Hao, Y.; Zhu, Y.J.; Zou, S.; Zhou, P.; Hu, Y.W.; Zhao, Q.X.; Gu, L.N.; Zhang, H.Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, J. Metabolic Syndrome and Psoriasis: Mechanisms and Future Directions. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 711060.

- Jones, V.A.; Patel, P.M.; Wilson, C.; Wang, H.; Ashack, K.A. Complementary and alternative medicine treatments for common skin diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAAD Int. 2020, 2, 76–93.

- Afifi, L.; Danesh, M.J.; Lee, K.M.; Beroukhim, K.; Farahnik, B.; Ahn, R.S.; Yan, D.; Singh, R.K.; Nakamura, M.; Koo, J.; et al. Dietary Behaviors in Psoriasis: Patient-Reported Outcomes from a, U.S. National Survey. Dermatol. Ther. 2017, 7, 227–242.

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M.V.; Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 320, C375–C391.

- Naldi, L.; Conti, A.; Cazzaniga, S.; Patrizi, A.; Pazzaglia, M.; Lanzoni, A.; Veneziano, L.; Pellacani, G.; the Psoriasis Emilia Romagna Study Group. Diet and physical exercise in psoriasis: A randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2014, 170, 634–642.

- Lewandowska, M.; Dunbar, K.; Kassam, S. Managing Psoriatic Arthritis With a Whole Food Plant-Based Diet: A Case Study. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2021, 15, 402–406.

- Bonjour, M.; Gabriel, S.; Valencia, A.; Goldhamer, A.C.; Myers, T.R. Challenging Case in Clinical Practice: Prolonged Water-Only Fasting Followed by an Exclusively Whole-Plant-Food Diet in the Management of Severe Plaque Psoriasis. Integr. Complement. Ther. 2022, 28, 85–87.

- Nutten, S. Atopic dermatitis: Global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66 (Suppl. S1), 8–16.

- Kim, J.; Kim, B.E.; Leung, D.Y.M. Pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis: Clinical implications. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019, 40, 84–92.

- Frazier, W.; Bhardwaj, N. Atopic Dermatitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2020, 101, 590–598.

- Fusano, M. Veganism in acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis: Benefits of a plant-based diet. Clin. Dermatol. 2022.

- Tanaka, T.; Kouda, K.; Kotani, M.; Takeuchi, A.; Tabei, T.; Masamoto, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Takigawa, M.; Suemura, M.; Takeuchi, H.; et al. Vegetarian diet ameliorates symptoms of atopic dermatitis through reduction of the number of peripheral eosinophils and of PGE2 synthesis by monocytes. J. Physiol. Anthropol. Appl. Hum. Sci. 2001, 20, 353–361.

- Kouda, K.; Tanaka, T.; Kouda, M.; Takeuchi, H.; Takeuchi, A.; Nakamura, H.; Takigawa, M. Low-energy diet in atopic dermatitis patients: Clinical findings and DNA damage. J. Physiol. Anthropol. Appl. Hum. Sci. 2000, 19, 225–228.

- Toyoda, M.; Morohashi, M. Pathogenesis of acne. Med. Electron. Microsc. 2001, 34, 29–40.

- Beylot, C.; Auffret, N.; Poli, F.; Claudel, J.P.; Leccia, M.T.; Del Giudice, P.; Dreno, B. Propionibacterium acnes: An update on its role in the pathogenesis of acne. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 28, 271–278.

- Dréno, B. What is new in the pathophysiology of acne, an overview. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31 (Suppl. S5), 8–12.

- Suppiah, T.S.S.; Sundram, T.K.M.; Tan, E.S.S.; Lee, C.K.; Bustami, N.A.; Tan, C.K. Acne vulgaris and its association with dietary intake: A Malaysian perspective. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 27, 1141–1145.

- Baldwin, H.; Tan, J. Effects of Diet on Acne and Its Response to Treatment. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 22, 55–65.

- Stewart, T.J.; Bazergy, C. Hormonal and dietary factors in acne vulgaris versus controls. Dermato-Endocrinology 2018, 10, e1442160.

- Aalemi, A.K.; Anwar, I.; Chen, H. Dairy consumption and acne: A case control study in Kabul, Afghanistan. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 12, 481–487.

- Youssef, E.M.K.; Youssef, M.K.E. Diet and Acne in Upper Egypt. Am. J. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 3, 13–22.

- Song, J.H.; Bae, E.Y.; Choi, G.; Hyun, J.W.; Lee, M.Y.; Lee, H.W.; Chae, S. Protective effect of mango (Mangifera indica L.) against UVB-induced skin aging in hairless mice. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2013, 29, 84–89.

- Hasler, C.M.; Kundrat, S.; Wool, D. Functional foods and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2000, 2, 467–475.

- Lebaka, V.R.; Wee, Y.J.; Ye, W.; Korivi, M. Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds in Three Different Parts of Mango Fruit. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 741.

- Dattola, A.; Silvestri, M.; Bennardo, L.; Passante, M.; Scali, E.; Patruno, C.; Nisticò, S.P. Role of Vitamins in Skin Health: A Systematic Review. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2020, 9, 226–235.

- Fam, V.W.; Holt, R.R.; Keen, C.L.; Sivamani, R.K.; Hackman, R.M. Prospective Evaluation of Mango Fruit Intake on Facial Wrinkles and Erythema in Postmenopausal Women: A Randomized Clinical Pilot Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3381.

- Quirós-Sauceda, A.E.; Oliver Chen, C.Y.; Blumberg, J.B.; Astiazaran-Garcia, H.; Wall-Medrano, A.; González-Aguilar, G.A. Processing “Ataulfo” Mango into Juice Preserves the Bioavailability and Antioxidant Capacity of Its Phenolic Compounds. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1082.

- Dreher, M.L. A comprehensive review of almond clinical trials on weight measures, metabolic health biomarkers and outcomes, and the gut microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1968.

- Foolad, N.; Vaughn, A.R.; Rybak, I.; Burney, W.A.; Chodur, G.M.; Newman, J.W.; Steinberg, F.M.; Sivamani, R.K. Prospective randomized controlled pilot study on the effects of almond consumption on skin lipids and wrinkles. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 3212–3217.

- Rybak, I.; Carrington, A.E.; Dhaliwal, S.; Hasan, A.; Wu, H.; Burney, W.; Maloh, J.; Sivamani, R.K. Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial on the Effects of Almonds on Facial Wrinkles and Pigmentation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 785.

- Dreher, M.L.; Davenport, A.J. Hass Avocado Composition and Potential Health Effects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 738.

- Henning, S.M.; Guzman, J.B.; Thames, G.; Yang, J.; Tseng, C.H.; Heber, D.; Kim, J.; Li, Z. Avocado Consumption Increased Skin Elasticity and Firmness in Women—A Pilot Study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 4028–4034.

- Mann, E.A.; Bae, E.; Kostyuchek, D.; Chung, H.J.; McGee, J.S. The Gut Microbiome: Human Health and Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Ann. Dermatol. 2020, 32, 265.

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, M. Skin Barrier Function and the Microbiome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13071.

- Pessemier, B.; De Grine, L.; Debaere, M.; Maes, A.; Paetzold, B.; Callewaert, C. Gut-Skin Axis: Current Knowledge of the Interrelationship between Microbial Dysbiosis and Skin Conditions. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 353.

- Levy, M.; Blacher, E.; Elinav, E. Microbiome, metabolites and host immunity. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017, 35, 8–15.

- Coates, M.; Lee, M.J.; Norton, D.; MacLeod, A.S. The Skin and Intestinal Microbiota and Their Specific Innate Immune Systems. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 496479.

- Rhodes, L.E.; Darby, G.; Massey, K.A.; Clarke, K.A.; Dew, T.P.; Farrar, M.D.; Bennett, S.; Watson, R.E.B.; Williamson, G.; Nicolaou, A. Oral green tea catechin metabolites are incorporated into human skin and protect against UV radiation-induced cutaneous inflammation in association with reduced production of pro-inflammatory eicosanoid 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 891–900.

- Giampieri, F.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Mazzoni, L.; Forbes-Hernandez, T.Y.; Gasparrini, M.; Gonzàlez-Paramàs, A.M.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Quiles, J.L.; Bompadre, S.; Mezzetti, B.; et al. Polyphenol-Rich Strawberry Extract Protects Human Dermal Fibroblasts against Hydrogen Peroxide Oxidative Damage and Improves Mitochondrial Functionality. Molecules 2014, 19, 7798–7816.

- Mahmud, M.R.; Akter, S.; Tamanna, S.K.; Mazumder, L.; Esti, I.Z.; Banerjee, S.; Akter, S.; Hasan, R.; Acharjee, M.; Hossain, S.; et al. Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: Gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2096995.

- Sinha, S.; Lin, G.; Ferenczi, K. The skin microbiome and the gut-skin axis. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 39, 829–839.

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–563.

- Sánchez-Tapia, M.; Tovar, A.R.; Torres, N. Diet as Regulator of Gut Microbiota and its Role in Health and Disease. Arch. Med. Res. 2019, 50, 259–268.

- Jefferson, A.; Adolphus, K. The Effects of Intact Cereal Grain Fibers, Including Wheat Bran on the Gut Microbiota Composition of Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 33.

- Fang, Z.; Pan, T.; Li, L.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W.; Lu, W. Bifidobacterium longum mediated tryptophan metabolism to improve atopic dermatitis via the gut-skin axis. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2044723.

- Li, Y.; Wang, D.D.; Satija, A.; Ivey, K.L.; Li, J.; E Wilkinson, J.; Li, R.; Baden, M.; Chan, A.T.; Huttenhower, C.; et al. Plant-Based Diet Index and Metabolic Risk in Men: Exploring the Role of the Gut Microbiome. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 2780.

- Peters, B.A.; Xing, J.; Chen, G.C.; Usyk, M.; Wang, Z.; McClain, A.C.; Thyagarajan, B.; Daviglus, M.L.; Sotres-Alvarez, D.; Hu, F.B.; et al. Healthy dietary patterns are associated with the gut microbiome in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 117, 540–552.

- Koponen, K.K.; Salosensaari, A.; Ruuskanen, M.O.; Havulinna, A.S.; Männistö, S.; Jousilahti, P.; Palmu, J.; Salido, R.; Sanders, K.; Brennan, C.; et al. Associations of healthy food choices with gut microbiota profiles. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 605–616.

- Ghosh, T.S.; Rampelli, S.; Jeffery, I.B.; Santoro, A.; Neto, M.; Capri, M.; Giampieri, E.; Jennings, A.; Candela, M.; Turroni, S.; et al. Mediterranean diet intervention alters the gut microbiome in older people reducing frailty and improving health status: The NU-AGE 1-year dietary intervention across five European countries. Gut 2020, 69, 1218–1228.

- Cani, P.D.; Bibiloni, R.; Knauf, C.; Waget, A.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Delzenne, N.M.; Burcelin, R. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1470–1481.

- Nayak, R.R. Western Diet and Psoriatic-Like Skin and Joint Diseases: A Potential Role for the Gut Microbiota. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 1630–1632.

- Shi, Z.; Wu, X.; Yu, S.; Huynh, M.; Jena, P.K.; Nguyen, M.; Wan, Y.J.Y.; Hwang, S.T. Short-Term Exposure to a Western Diet Induces Psoriasiform Dermatitis by Promoting Accumulation of IL-17A–Producing γδ T Cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 1815–1823.

- Melnik, B.C. Dietary intervention in acne: Attenuationof increased mTORC1 signaling promoted by Western diet. Dermatoendocrinol 2012, 4, 20–32.

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 492–506.

- Seethaler, B.; Nguyen, N.K.; Basrai, M.; Kiechle, M.; Walter, J.; Delzenne, N.M.; Bischoff, S.C. Short-chain fatty acids are key mediators of the favorable effects of the Mediterranean diet on intestinal barrier integrity: Data from the randomized controlled LIBRE trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 116, 928–942.

- Trompette, A.; Pernot, J.; Perdijk, O.; Alqahtani, R.A.A.; Domingo, J.S.; Camacho-Muñoz, D.; Wong, N.C.; Kendall, A.C.; Wiederkehr, A.; Nicod, L.P.; et al. Gut-derived short-chain fatty acids modulate skin barrier integrity by promoting keratinocyte metabolism and differentiation. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 908–926.

- Xiao, X.; Hu, X.; Yao, J.; Cao, W.; Zou, Z.; Wang, L.; Qin, H.; Zhong, D.; Li, Y.; Xue, P.; et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in inflammatory skin diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1083432.

- Lazar, V.; Ditu, L.M.; Pircalabioru, G.G.; Gheorghe, I.; Curutiu, C.; Holban, A.M.; Picu, A.; Petcu, L.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Aspects of Gut Microbiota and Immune System Interactions in Infectious Diseases, Immunopathology, and Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1830.

- Wang, D.D.; Nguyen, L.H.; Li, Y.; Yan, Y.; Ma, W.; Rinott, E.; Ivey, K.L.; Shai, I.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B.; et al. The gut microbiome modulates the protective association between a Mediterranean diet and cardiometabolic disease risk. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 333–343.

- Asuncion, P.; Liu, C.; Castro, R.; Yon, V.; Rosas, M.; Hooshmand, S.; Kern, M.; Hong, M.Y. The effects of fresh mango consumption on gut health and microbiome—Randomized controlled trial. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 2069–2078.

- Schade, L.; Mesa, D.; Faria, A.R.; Santamaria, J.R.; Xavier, C.A.; Ribeiro, D.; Hajar, F.N.; Azevedo, V.F. The gut microbiota profile in psoriasis: A Brazilian case-control study. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 74, 498–504.

- Watanabe, S.; Narisawa, Y.; Arase, S.; Okamatsu, H.; Ikenaga, T.; Tajiri, Y.; Kumemura, M. Differences in fecal microflora between patients with atopic dermatitis and healthy control subjects. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003, 111, 587–591.

- Zhang, J.; Loman, L.; Oldhoff, M.; Schuttelaar, M.L.A. Association between moderate to severe atopic dermatitis and lifestyle factors in the Dutch general population. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 1523–1535.

- Smith, M.; Wright, N.; McHugh, P.; Duncan, B. Remission of long-standing livedoid vasculopathy using a whole foods plant-based diet with symptoms recurrent on re-challenge with standard Western diet. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e237895.

- Solanki, V.K.; Nair, P.M.K. Lifestyle medicine approach in managing pemphigus vulgaris: A case report. Explore, 2023; in press.

- Nongnuch, A.; Davenport, A. The effect of vegetarian diet on skin autofluorescence measurements in haemodialysis patients. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1040–1043.