Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Jiangpeng He and Version 2 by Jessie Wu.

Food classification serves as the basic step of image-based dietary assessment to predict the types of foods in each input image. However, foods in real-world scenarios are typically long-tail distributed, where a small number of food types are consumed more frequently than others, which causes a severe class imbalance issue and hinders the overall performance. In addition, none of the existing long-tailed classification methods focus on food data, which can be more challenging due to the inter-class similarity and intra-class diversity between food images.

- food classification

- long-tail distribution

- image-based dietary assessment

- benchmark datasets

- food consumption frequency

- neural networks

1. Introduction

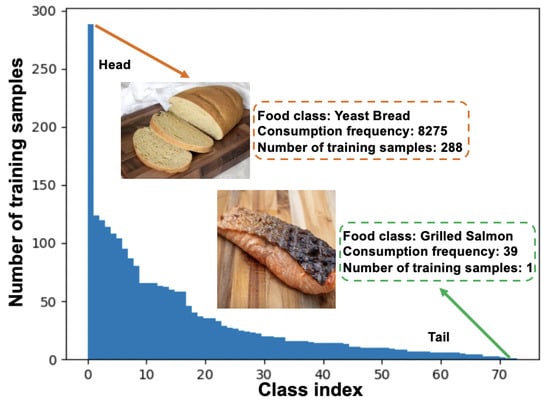

Accurate identification of food is critical to image-based dietary assessment [1][2][1,2], which facilitates matching the food to the proper identification of that food in a nutrient database with the corresponding nutrient composition [3]. Such linkage makes it possible to determine dietary links to health and diseases such as diabetes [4]. Dietary assessment, therefore, is very important to healthcare-related applications [5][6][5,6] due to recent advances in novel computation approaches and new sensor devices. In addition, the application of image-based dietary assessments on mobile devices has received increasing attention in recent years [7][8][9][10][7,8,9,10], which can serve as a more efficient platform to alleviate the burden on participants and enhance the adaptability to diverse real-world situations. The performance of image-based dietary assessment relies on the accurate prediction of foods in the captured eating scene images. However, most current food classification systems [11][12][13][11,12,13] are developed based on class-balanced food image datasets such as Food-101 [14], where each food class contains the same number of training data. However, this rarely happens in the real world since food images usually have a long-tailed distribution, where a small portion of food classes (i.e., the head class) contain abundant samples for training, while most food classes (i.e., the tail class) have only a few samples, as shown in Figure 1. Thus, long-tailed classification, defined as the extreme class imbalance problem, leads to classification bias towards head classes and poor generalization ability for recognizing tail food classes. Therefore, the food classification performance in the real world may drop significantly without considering the class imbalance issue, which would in turn constrain the applications of image-based dietary assessments. ReIn thisearchers work, we analyze the long-tailed class distribution problem for food image classification and develop a framework to address the issue with the objective of minimizing the performance gap when applied in real-life food-related applications.

Figure 1. An overview of the VFN-LT that exhibits a real-world long-tailed food distribution. The number of training samples is assigned based on the consumption frequency, which is matched through NHANES from 2009 to 2016 among 17,796 healthy U.S. adults.

As few existing long-tailed image classification methods target food images, two benchmark Long-Tailed food datasets are introduced at first, including Food101-LT and VFN-LT. Similar to [15], Food101-LT is constructed as a long-tailed version of the original balanced Food101 [14] dataset by following the Pareto distribution. In addition, as shown in Figure 1, VFN-LT is also used and provides a new and valuable long-tailed distributed food dataset where the number of samples for each food class exhibits the distribution of consumption frequency [16], defined as how often a food is consumed in one day according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.html, accessed on 21 April 2023) (NHANES) from 2009 to 2016 among 17,796 U.S. healthy adults aged 20 to 65, i.e., the head classes of VFN-LT are the most frequently consumed foods in the real world for the population represented. It is also worth noting that both Food101-LT and VFN-LT are of a heavier-tailed distribution than most existing benchmarks such as CIFAR100-LT [17], which is simulated by following a general exponential distribution.

An intuitive way to address the class imbalance issue is to undersample the head classes and oversample the tail classes to obtain a balanced training set containing a similar number of samples for all classes. However, there are two major challenges: (1) How to undersample the head classes to remove the redundant samples without compromising the original performance. (2) How to oversample the tail classes to increase the model generalization ability as naive repeated random oversampling can further intensify the overfitting problem, resulting in a worse performance especially in heavy-tailed distributions. In addition, food images are known to be more complicated than general objects for various downstream tasks such as classification, segmentation and image generation due to their inter-class similarity and intra-class diversity, which becomes more challenging in long-tailed data distributions with a severe class imbalance issue.

2. Food Classification

The most common deep-learning-based methods [18][19] for food classification apply off-the-shelf models such as ResNet [19][20] with pre-training on ImageNet [20][21] to fine tune [21][22] food image datasets [22][23][24][23,24,25] such as Food-101 [14]. To achieve a higher performance and address the issue of inter-class similarity and intra-class diversity, the most recent work proposed the construction of a semantic hierarchy based on both visual similarity [11] and nutrition information [25][26] to perform optimization on each level. In addition, food classification has also been studied under different scenarios such as large-scale recognition [12], few-shot learning [26][27] and continual learning [27][28][28,29]. However, none of the existing methods study long-tailed food classification where the severe class imbalance issue in real life may significantly degrade the performance. Finally, though the most recent work targets the multi-labeled ingredient recognition [29][30], the focus of this research is on long-tailed single food classification, where each image contains only one food class and the training samples for each class are heavily imbalanced.

3. Long-Tailed Classification

Existing long-tailed classification methods can be categorized into two main groups including: (i) re-weighting and (ii) re-sampling. Re-weighting-based methods aim to mitigate the class imbalance problem by assigning tail classes or samples with higher weights than the head classes. The inverse of class frequency is widely used to generate the weights for each class, as in [30][31][31,32]. In addition, a variety of loss functions have been proposed to adjust weights during training, including label-distribution-aware margin loss [17], balanced Softmax [32][33] and instance-based focal loss [33][34]. Alternatively, re-sampling-based methods aim to generate a balanced training distribution by undersampling the head classes as described in [34][35] and oversampling the tail classes as shown in [34][35][35,36], in which all tail classes were oversampled until class balance was achieved. However, a drawback to undersampling is that valuable information of the head classes can be lost and naive oversampling can further intensify the overfitting problem due to the lack of diversity of repeated samples. A recent work [36][18] proposed performing oversampling by leveraging CutMix [37] to cut a randomly generated region in tail class samples and mix it with head class samples. However, the performance of existing methods on food data still remain under-explored, presenting additional challenges to other object recognition.