Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Dean Liu and Version 1 by Rontani Jean-François.

Several studies set out to explain the presence of high proportions of photooxidation products of cis-vaccenic acid (generally considered to be of bacterial origin) in marine environments.

- attached bacteria

- phytodetritus

- oxidative damage

- singlet oxygen transfer

- solar irradiance

1. Introduction

Phototrophic organisms carry out photosynthetic reactions that convert chlorophyll into a singlet excited state (1Chl) under the action of light. A small fraction of the 1Chl formed can undergo intersystem crossing to produce a longer-living triplet state, 3Chl [1]. 3Chl can directly damage unsaturated membrane components through type I reactions (i.e., involving radicals) [1], but it can also react with ground-state oxygen (3O2) to generate singlet oxygen (1O2) and, although to a lesser extent, superoxide ions (O2−•). In living cells, the toxic effects of 3Chl and 1O2 are limited by endogenous quenchers or scavengers (carotenoids, tocopherols, ascorbic acid, superoxide dismutase enzymes) [2[2][3],3], but this is not the case during cell senescence or cell death. When cells senesce, the slowdown of 1Chl consumption in the photosynthetic reactions accelerates the conversion of 1Chl into 3Chl and, thus, into 1O2, which then saturates the photoprotective system and ultimately causes photodamage [4,5][4][5]. During the senescence of phototrophic organisms, type II photosensitized oxidation processes that mainly involve 1O2 strongly damage unsaturated membrane lipids. The very high reactivity of 1O2 with unsaturated compounds results from its strong electrophilicity and the lack of spin restriction that normally hinders 3O2 reacting with unsaturated compounds [6].

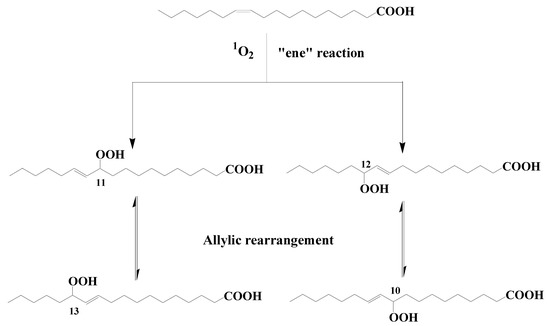

Type II photosensitized oxidation processes act intensively on several unsaturated lipids, including chlorophyll itself but also unsaturated fatty acids, sterols, some n-alkenes, some highly branched isoprenoid (HBI) alkenes, carotenoids, and tocopherols (for review, see [5,7,8,9][5][7][8][9]). Type II photosensitized oxidation of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) involves a direct reaction of 1O2 with the carbon–carbon double bond via a concerted ‘ene’ addition [10], leading to the formation of hydroperoxides at each end of the original double bond [11] (see Figure 1 showing oxidation of cis-vaccenic acid). These hydroperoxides, which possess an allylic trans-double bond can subsequently undergo stereoselective radical allylic rearrangement and afford two other isomers with a trans-double bond [11,12][11][12] (Figure 1). Type II photosensitized oxidation of MUFAs, thus, leads to the formation of four isomeric allylic hydroperoxyacids, which are generally converted to their corresponding hydroxyacids by NaBH4 reduction for quantification in natural samples [13]. This approach has been used to detect high levels of photoproducts of phytoplanktonic MUFAs in several marine particulate and sediment samples (for a recent review see [9]).

Figure 1. Type II photosensitized oxidation of cis-vaccenic acid and subsequent allylic rearrangement of the hydroperoxyacids formed.

Surprisingly, photoproducts of octadec-11(cis)-enoic acid (cis-vaccenic acid) have also been detected in a number of different zones of the oceans [7,8,9,14,15][7][8][9][14][15] and sometimes in similar or even higher proportions (relative to the parent acid) than photoproducts of phytoplanktonic MUFAs. Cis-vaccenic acid has been proposed as a useful biological marker for bacteria in the marine environment, based on its higher relative concentrations in bacteria than in other organisms [16,17,18,19,20][16][17][18][19][20]. However, given that heterotrophic bacteria lack photosynthetic system, the presence of high proportions of these photoproducts was a very surprising finding.

2. Potential Sources of Photoproducts of cis-Vaccenic Acid in Oceans

2.1. Photooxidation of Aerobic Anoxygenic Phototrophic Bacteria (AAPB)

Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria (AAPB) are an important group of microorganisms inhabiting the euphotic zones of oceans and freshwater or saline lakes [21]. They do not form a monophyletic clade but are widely distributed within Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, and Gammaproteobacteria classes [22,23][22][23]. These bacteria perform a heterotrophic metabolism because they require organic carbon for growth, but they can also use photosynthesis as a supplemental energy source [24]. Due to their ability to obtain extra energy from light, AAPB can have a higher impact on the degradation of organic matter than strict heterotrophs [25]. It has been previously demonstrated that AAPB are widely distributed in the open ocean [26,27,28][26][27][28]. The induction of type II photosensitized oxidation processes in these organisms, which contain bacteriochlorophyll (which is a highly efficient photosensitizer [29]) and high proportions of cis-vaccenic acid in their membranes [30,31][30][31] could, therefore, be at the origin of the presence of cis-vaccenic acid photoproducts in the samples investigated. To test this hypothesis, senescent cells of Erythrobacter sp. strain NAP1 and Roseobacter sp. strain COL2P were exposed to photosynthetically available radiation (PAR) [32]. The profile of oxidation products of cis-vaccenic acid obtained after exposure to PAR did not correspond to the profile observed in situ. In fact, as wresearchers have seen previously, the attack of cis-vaccenic acid by 1O2-mediated processes only produces trans allylic hydroperoxyacids (Figure 1), whereas the irradiation of senescent AAPB results in the formation of high proportions of cis isomers, which are characteristic of radical oxidation processes [33]. Previous research shows that the 1O2 produced in senescent phytoplankton cells (for a review see [9]), but also in purple sulfur bacteria (Thiohalocapsa halophila and Halochromatium salexigens) [34] by type II chlorophyll or bacteriochlorophyll-photosensitized processes intensively attacks the phytyl side-chain of these pigments, affording a specific photoproduct (3-methylidene-7,11,15-trimethylhexadecan-1,2-diol) [8]. The fact that this compound is not found after irradiation of AAPB confirms that 1O2 is only very weakly produced during the senescence of these organisms. The oxidation of cis-vaccenic acid in AAPB, thus, appears to involve radical degradation processes and is clearly not at the origin of the presence of high proportions of cis-vaccenic acid photooxidation products resulting from 1O2-mediated processes in the oceans.2.2. Transfer of Photochemically Produced

1

O

2

from Senescent Phytoplanktonic Cells to Their Attached Heterotrophic Bacteria

Another explanation for the unexpected presence of cis-vaccenic acid photoproducts in marine systems could be 1O2 transfer in attached heterotrophic bacteria during the senescence of phytoplankton. Bacteria are known to colonize phytoplankton-derived particles [35,36][35][36]. Figure 2 shows an example of the close association between bacteria and phytoplankton. Senescent phytoplanktonic cells provide hydrophobic micro-environments in which the lifetime and the potential diffusive distance of 1O2 could be long enough to induce type II photosensitized oxidation processes in attached bacteria. Indeed, the intracellular sphere of activity of 1O2 has recently been re-evaluated [37] and the radius of this sphere of activity from the point of production appeared to be larger than previously thought. It is estimated at between 155 and 340 nm [37[37][38][39],38,39], which is a large-enough distance to allow 1O2 to cross the cell membranes of phytoplanktonic cells (thickness ranging from 70 to 80 nm) [37,40,41][37][40][41] and, thus, reach attached bacteria.

Figure 2. Scanning electron microscopy image of a strain of the diatom Skeletonema costatum colonized with heterotrophic bacteria (adapted from [32]).

References

- Knox, J.P.; Dodge, A.D. Singlet Oxygen and Plants. Phytochemistry 1985, 24, 889–896.

- Foote, C.S. Photosensitized Oxidation and Singlet Oxygen: Consequences in Biological Systems. In Free Radicals in Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1976; Volume 2, p. 85.

- Halliwell, B. Oxidative Damage, Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidant Protection in Chloroplasts. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1987, 44, 327–340.

- Merzlyak, M.N.; Hendry, G.A. Free Radical Metabolism, Pigment Degradation and Lipid Peroxidation in Leaves during Senescence. Proc. R. Soc. Edinb. Sect. B Biol. Sci. 1994, 102, 459–471.

- Rontani, J.-F. Visible Light-Dependent Degradation of Lipidic Phytoplanktonic Components during Senescence: A Review. Phytochemistry 2001, 58, 187–202.

- Dmitrieva, V.A.; Tyutereva, E.V.; Voitsekhovskaja, O.V. Singlet Oxygen in Plants: Generation, Detection, and Signaling Roles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3237.

- Rontani, J.-F.; Charriere, B.; Forest, A.; Heussner, S.; Vaultier, F.; Petit, M.; Delsaut, N.; Fortier, L.; Sempere, R. Intense Photooxidative Degradation of Planktonic and Bacterial Lipids in Sinking Particles Collected with Sediment Traps across the Canadian Beaufort Shelf (Arctic Ocean). Biogeosciences 2012, 9, 4787–4802.

- Rontani, J.-F.; Amiraux, R.; Smik, L.; Wakeham, S.G.; Paulmier, A.; Vaultier, F.; Sun-Yong, H.; Jun-Oh, M.; Belt, S.T. Type II Photosensitized Oxidation in Senescent Microalgal Cells at Different Latitudes: Does Low under-Ice Irradiance in Polar Regions Enhance Efficiency? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 779, 146363.

- Rontani, J.-F.; Belt, S.T. Photo-and Autoxidation of Unsaturated Algal Lipids in the Marine Environment: An Overview of Processes, Their Potential Tracers, and Limitations. Org. Geochem. 2020, 139, 103941.

- Frimer, A.A. The Reaction of Singlet Oxygen with Olefins: The Question of Mechanism. Chem. Rev. 1979, 79, 359–387.

- Frankel, E. Lipid Oxidation; The Oily Press LTD.: Dundee, UK, 1998.

- Frankel, E.N.; Neff, W.; Bessler, T. Analysis of Autoxidized Fats by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry: V. Photosensitized Oxidation. Lipids 1979, 14, 961–967.

- Rontani, J.-F. Use of Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Techniques (GC-MS, GC-MS/MS and GC-QTOF) for the Characterization of Photooxidation and Autoxidation Products of Lipids of Autotrophic Organisms in Environmental Samples. Molecules 2022, 27, 1629.

- Marchand, D.; Rontani, J.-F. Characterisation of Photo-Oxidation and Autoxidation Products of Phytoplanktonic Monounsaturated Fatty Acids in Marine Particulate Matter and Recent Sediments. Org. Geochem. 2001, 32, 287–304.

- Christodoulou, S.; Marty, J.-C.; Miquel, J.-C.; Volkman, J.K.; Rontani, J.-F. Use of Lipids and Their Degradation Products as Biomarkers for Carbon Cycling in the Northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Chem. 2009, 113, 25–40.

- Perry, G.; Volkman, J.; Johns, R.; Bavor Jr, H. Fatty Acids of Bacterial Origin in Contemporary Marine Sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1979, 43, 1715–1725.

- Volkman, J.; Johns, R.; Gillan, F.; Perry, G.; Bavor Jr, H. Microbial Lipids of an Intertidal Sediment—I. Fatty Acids and Hydrocarbons. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1980, 44, 1133–1143.

- Sicre, M.-A.; Paillasseur, J.-L.; Marty, J.-C.; Saliot, A. Characterization of Seawater Samples Using Chemometric Methods Applied to Biomarker Fatty Acids. Org. Geochem. 1988, 12, 281–288.

- Keweloh, H.; Heipieper, H.J. Trans Unsaturated Fatty Acids in Bacteria. Lipids 1996, 31, 129–137.

- Westbroek, P.; De Jong, E.; Van der Wal, P.; Borman, A.; De Vrind, J.; Kok, D.; De Bruijn, W.; Parker, S. Mechanism of Calcification in the Marine Alga Emiliania Huxleyi. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. B Biol. Sci. 1984, 304, 435–444.

- Zheng, Q.; Liu, Y.; Jeanthon, C.; Zhang, R.; Lin, W.; Yao, J.; Jiao, N. Geographic Impact on Genomic Divergence as Revealed by Comparison of Nine Citromicrobial Genomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 7205–7216.

- Saini, A.; Panwar, D.; Panesar, P.S.; Bera, M.B. Encapsulation of Functional Ingredients in Lipidic Nanocarriers and Antimicrobial Applications: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1107–1134.

- Thiel, V.; Tank, M.; Bryant, D.A. Diversity of Chlorophototrophic Bacteria Revealed in the Omics Era. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 21–49.

- Kolber, Z.S.; Gerald, F.; Plumley; Lang, A.S.; Beatty, J.T.; Blankenship, R.E.; VanDover, C.L.; Vetriani, C.; Koblizek, M.; Rathgeber, C. Contribution of Aerobic Photoheterotrophic Bacteria to the Carbon Cycle in the Ocean. Science 2001, 292, 2492–2495.

- Daniel, C. Regrowth of Subtropical Aerobic Anoxygenic Photoheterotrophic Bacteria upon Grazer Removal: A Case Study of Surface Waters Collected from the Southern Pensacola Bay. Master’s Thesis, University of West Florida, Pensacola, FL, USA, 2022.

- Kolber, Z.S.; Van Dover, C.; Niederman, R.; Falkowski, P. Bacterial Photosynthesis in Surface Waters of the Open Ocean. Nature 2000, 407, 177–179.

- Lehours, A.-C.; Enault, F.; Boeuf, D.; Jeanthon, C. Biogeographic Patterns of Aerobic Anoxygenic Phototrophic Bacteria Reveal an Ecological Consistency of Phylogenetic Clades in Different Oceanic Biomes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4105.

- Gazulla, C.R.; Auladell, A.; Ruiz-González, C.; Junger, P.C.; Royo-Llonch, M.; Duarte, C.M.; Gasol, J.M.; Sánchez, O.; Ferrera, I. Global Diversity and Distribution of Aerobic Anoxygenic Phototrophs in the Tropical and Subtropical Oceans. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 2222–2238.

- Yang, C.-H.; Huang, K.-S.; Wang, Y.-T.; Shaw, J.-F. A Review of Bacteriochlorophyllides: Chemical Structures and Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 1293.

- Rontani, J.-F.; Christodoulou, S.; Koblizek, M. GC-MS Structural Characterization of Fatty Acids from Marine Aerobic Anoxygenic Phototrophic Bacteria. Lipids 2005, 40, 97–108.

- Kopejtka, K.; Zeng, Y.; Kaftan, D.; Selyanin, V.; Gardian, Z.; Tomasch, J.; Sommaruga, R.; Koblížek, M. Characterization of the Aerobic Anoxygenic Phototrophic Bacterium Sphingomonas sp. AAP5. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 768.

- Rontani, J.; Koblížek, M.; Beker, B.; Bonin, P.; Kolber, Z.S. On the Origin of Cis-vaccenic Acid Photodegradation Products in the Marine Environment. Lipids 2003, 38, 1085–1092.

- Porter, N.A.; Caldwell, S.E.; Mills, K.A. Mechanisms of Free Radical Oxidation of Unsaturated Lipids. Lipids 1995, 30, 277–290.

- Marchand, D.; Rontani, J.-F. Visible Light-Induced Oxidation of Lipid Components of Purple Sulfur Bacteria: A Significant Process in Microbial Mats. Org. Geochem. 2003, 34, 61–79.

- Unanue, M.; Azúa, I.; Arrieta, J.; Labirua-Iturburu, A.; Egea, L.; Iriberri, J. Bacterial Colonization and Ectoenzymatic Activity in Phytoplankton-Derived Model Particles: Cleavage of Peptides and Uptake of Amino Acids. Microb. Ecol. 1998, 35, 136–146.

- Kiørboe, T.; Grossart, H.-P.; Ploug, H.; Tang, K. Mechanisms and Rates of Bacterial Colonization of Sinking Aggregates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 3996–4006.

- Ogilby, P.R. Singlet Oxygen: There Is Indeed Something New under the Sun. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3181–3209.

- Klaper, M.; Fudickar, W.; Linker, T. Role of Distance in Singlet Oxygen Applications: A Model System. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7024–7029.

- Murotomi, K.; Umeno, A.; Shichiri, M.; Tanito, M.; Yoshida, Y. Significance of Singlet Oxygen Molecule in Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2739.

- Skovsen, E.; Snyder, J.W.; Lambert, J.D.; Ogilby, P.R. Lifetime and Diffusion of Singlet Oxygen in a Cell. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 8570–8573.

- Burot, C. Etude de La Dégradation Des Algues de Glace et Du Phytoplancton d’eau Libre En Zone Arctique: Impact de l’état de Stress Des Bactéries Associées à Ce Matériel Sur Sa Préservation et Sa Contribution Aux Sédiments. Ph.D. Thesis, Aix-Marseille University, Marseille, France, 2022.

- Petit, M.; Sempéré, R.; Vaultier, F.; Rontani, J.-F. Photochemical Production and Behavior of Hydroperoxyacids in Heterotrophic Bacteria Attached to Senescent Phytoplanktonic Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 11795–11815.

More