Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Layla Simon and Version 1 by Layla Simon.

Advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages lead to exacerbated inflammation and oxidative stress. Patients with CKD in stage 5 need renal hemodialysis (HD) to remove toxins and waste products. However, this renal replacement therapy (RRT) is inefficient in controlling inflammation. Regular curcumin consumption has been shown to reduce inflammation and oxidative stress in subjects with chronic pathologies, suggesting that the daily intake of curcumin may alleviate these conditions in HD patients. This entry summarized the article (https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102239).

- chronic kidney disease

- renal replacement therapies

- inflammation

- haemodyalisis

- ROS

1. Mechanisms and Consequences of HD in the Organism

CKD is primarily caused by the growing elderly population and the increasing occurrence of diabetes and hypertension worldwide. Research predicts that by 2030, the number of individuals globally requiring RRT will rise to 5.4 million, with the highest growth rates anticipated in Asia and Latin America. In these regions, rapid urbanization and globalization have led to overlapping disease burdens, resulting in high and growing rates of infectious diseases, diabetes and hypertension. Furthermore, in developing countries, CKD is exacerbated by environmental pollution, pesticide exposure, analgesic abuse, the use of herbal medications and the ingestion of unregulated food additives. Dialysis remains the most prevalent RRT in end-stage CKD (stage 5), and HD is the most commonly applied modality globally [1].

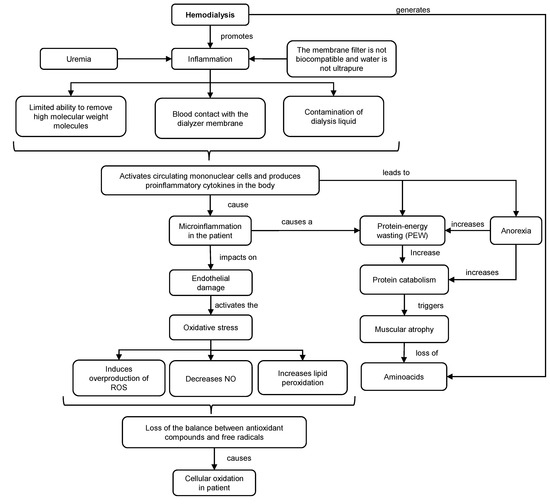

Dialysis is a purification technique that filters toxic substances accumulated in the serum and water through a countercurrent extracorporeal circuit, consisting of a dialyzing filter and machine for the transport of blood and dialysate. This technique promotes inflammation and oxidative stress in patients (Figure 1). This situation is exacerbated (hyperinflammation) using non-biocompatible membranes and non-ultrapure water. Under these conditions, the capacity to remove high molecular weight molecules is diminished, and possible contamination of the dialysis fluid may occur. As a consequence, the transfer of bacteria into the blood could trigger the activation of mononuclear cells and the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 1 (IL-1) or TNF-α, which could promote inflammation, oxidative stress and deterioration of the immune system [2][3].

Figure 1. Mechanisms of inflammation and oxidative stress in HD. ROS: reactive oxygen species. NO: nitric oxide.

Mechanisms of inflammation and oxidative stress in HD. ROS: reactive oxygen species. NO: nitric oxide.

The inflammatory response generates endothelial damage, overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid peroxidation and decrease in the production of nitric oxide (NO). As a consequence, there is an increased oxidation in HD patients, resulting in a loss of balance between antioxidant compounds and free radical levels that contribute to cellular and tissue damage. Together with this, HD increases the concentration of hypercatabolic hormones, meanwhile decreasing the level of anabolic hormones [4].

Although the nutritional requirements are known, around 29% of women and 50% of men on HD have malnutrition or excessive weight. Moreover, the diets of HD patients are deficient in protein, energy, dietary fiber, vitamins B1, D and C, folates and Ca and Mg which aggravates the general status of patients [5]. Recommendations of suitable diets and supplementations with vitamins, minerals and alternative therapeutic compounds are mandatory to alleviate patient suffering.

2. Mechanisms of Action and Effect of Curcumin Consumption on the Control of Oxidative and Inflammatory Parameters in HD Patients

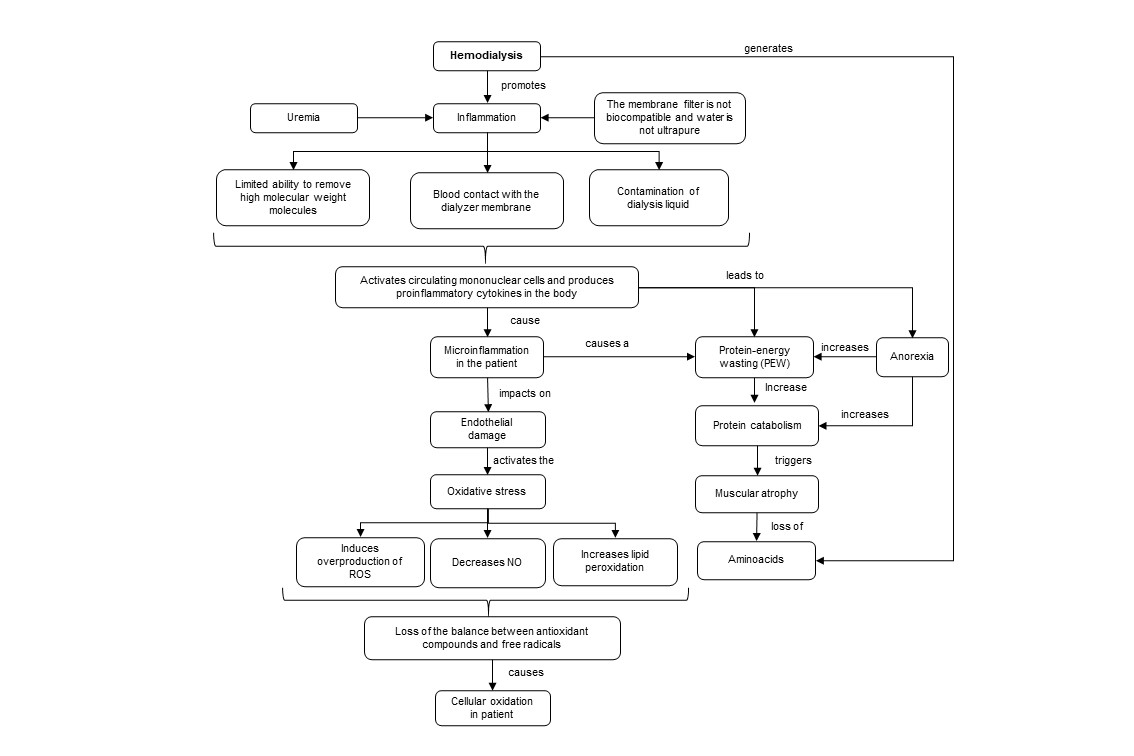

CKD in HD is a highly complex pathology, for that reason, it is necessary to supplement diets with several micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) and bioactive compounds (polyunsaturated fatty acids and polyphenols) [6][7][8][9]. In this sense, the intake of curcumin, a polyphenol of natural origin, stands out as an alternative for the control of various oxidative and inflammatory parameters associated with renal damage. Structurally, curcumin has a diketone hydrocarbon skeleton that unites two phenolic rings (Figure 2), which provide antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [10].

Figure 2. Chemical structure of curcumin.

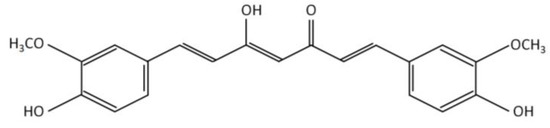

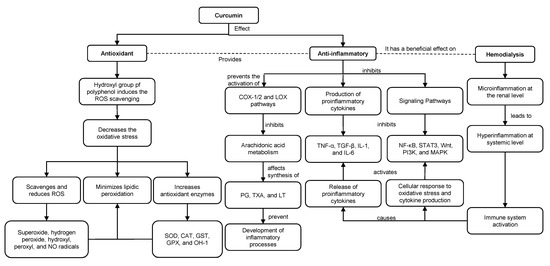

Studies indicate that the hydroxyl groups existing in the phenolic rings of curcumin regulate the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione-S-transferase (GST), glutathione peroxidase (GPX) and heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1). The phenolic rings are suggested to scavenge and reduce ROS such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl, peroxyl and NO radicals [11][12]. In addition, through ketone groups, curcumin exerts an antioxidant role in protecting cellular DNA from free radicals. As a consequence of this antioxidant potential, curcumin decreases inflammatory markers such as TNF-α, CRP and IL-1, serum creatinine and urea nitrogen (BUN) levels. Therefore, curcumin improves glomerular filtratio rate and attenuates renal dysfunction [11][13][14][15] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory roles of curcumin in HD. ROS: reactive oxygen species. NO: nitric oxide. SOD: superoxide dismutase. CAT: catalase. GST: glutathione-S-transferase. GPX: glutathione peroxidase. HO-1: heme oxygenase 1. COX-1: cyclooxygenase-1. COX-2: cyclooxygenase-2. LOX: lipoxygenase. PG: prostaglandins. TXA: thromboxanes. LT: leukotrienes.

Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory roles of curcumin in HD. ROS: reactive oxygen species. NO: nitric oxide. SOD: superoxide dismutase. CAT: catalase. GST: glutathione-S-transferase. GPX: glutathione peroxidase. HO-1: heme oxygenase 1. COX-1: cyclooxygenase-1. COX-2: cyclooxygenase-2. LOX: lipoxygenase. PG: prostaglandins. TXA: thromboxanes. LT: leukotrienes.

Along with previous evidence, curcumin has an antioxidant role by reducing lipid peroxidation and anti-inflammatory activity by binding to inflammatory molecules such as TNF-α, α1-human acidic α-glycoprotein (α1-GA), myeloid differentiation protein 2 (MD-2), cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and 2 (COX-2) and the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway [10]. Curcumin inhibits the COX and LOX pathways and, consequently, the metabolism of arachidonic acid, thereby affecting the synthesis of eicosanoids such as prostaglandins (PG), thromboxanes (TXA) and leukotrienes (LT), preventing the development of inflammatory processes and platelet aggregation [15][16]. Additionally, curcumin suppresses TNF-α and interleukin expression by inhibiting NF-κB. Moreover, curcumin suppresses STAT3, Wnt, PI3K and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent signaling pathways and modulates TGF-β expression and activity. Downstream of these events, curcumin exerts an anti-inflammatory role by decreasing proinflammatory cytokines [15][17].

At the preclinical level, curcumin administration exerts a protective effect on animal models for streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic nephropathy [18], cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity [19], 5/6 nephrectomy [20] and renal ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury [21]. In all of these studies, curcumin reduces oxidative and inflammatory markers regardless of the dose, the type of vehicle (pure curcumin, Arabic gum suspensions, carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), PBS, olive oil, nanoparticles) and the route of administration (feeding, oral gavage, intravenous, intraperitoneal). For example, in rats with STZ-induced diabetic nephropathy, chronic consumption of curcumin (orally and by oral gavage) attenuated renal dysfunction, macrophage infiltration and fibrosis [22], probably due to its antioxidant properties. Likewise, in rats with cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity, oral [19] and intraperitoneal [23] consumption of curcumin presented a protective effect, reduced the levels of oxidative and inflammatory markers and could be used as a potential coadjutant treatment. In 5/6 nephrectomized rats, curcumin attenuated oxidative stress, inflammation and renal fibrosis by modulating the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway [20], suggesting that it is a potential treatment for CKD. Similarly, rats with I/R injury subjected to daily oral administration of curcumin showed a reduction in urea and creatinine levels, an increase in glutathione (GSH), a decrease in malondialdehyde (MDA) and, consequently, reduced oxidative stress [24]. In addition, curcumin modulated the inflammatory response induced by I/R in the rat kidney through the activation of the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway [21].

Regarding clinical studies, HD patients who received 2.5 g of turmeric powder (95% curcumin) diluted in 100 mL of orange and carrot juice after each dialysis session/week for 3 months experienced a decrease in NF-kB and CRP [25]. Another intervention considered the effect of curcumin on plasma levels of uremic toxins, such as indoxyl sulfate, p cresyl sulfate (pCS) and 3-indoleacetic acid, in HD patients [26]. Similarly, the daily intake of 120 mg of nano-curcumin supplementation, delivered as three soft gelatin capsules with breakfast, lunch and dinner for 12 weeks, resulted in a significant decrease in inflammation markers (CRP, ICAM-1 and vascular cell adhesion protein 1 (VCAM-1)) in HD patients [27].

Likewise, the intake of turmeric capsules containing 22.1 mg of curcumin (three times a day for eight weeks) resulted in a significant decrease in CRP, IL-6 and TNF-α levels [14], as well as increased levels of antioxidants such as GPX, glutathione reductase (GR) and CAT [28] in HD patients, without adverse effects. This suggests that curcumin administration may have a coadjutant role in reducing inflammatory indicators and pCS at the intestinal level and increasing the levels of certain endogenous antioxidants in HD patients. In this regard, it would be inaccurate to assert that the doses used in these studies are adequate since they did not consider the body weight of HD patients. Moreover, these patients experience weight fluctuations before and after HD, making it challenging to determine the appropriate dosage.

3. Effect of Curcumin Bioaccessibility on Its Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effectiveness

Previously discussed clinical trials with curcumin have shown effectiveness in enhancing different inflammatory and antioxidant biomarkers in CKD patients. However, some of the evaluated doses could be higher than the acceptable daily intake established for curcumin (3 mg/day kg bw) by the European Food Safety Authority [29].

The hydrophobic nature of curcumin can limit its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity when administered orally. The insufficient solubility of orally administered curcumin results in low bioaccessibility during digestion, and as a consequence, there is a decrease in its availability. Furthermore, curcumin undergoes accelerated metabolism and is rapidly eliminated systemically, primarily through the feces [30].

To overcome these limitations, several technologies have been developed to enhance the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of curcumin at the intestinal level, thereby increasing its therapeutic potential. These techniques are based on triglycerides and tensoactive mixtures that physically isolate curcumin from gastrointestinal fluids and protect it from chemical degradation. By utilizing a digestible lipid phase, such as a triglyceride, fatty acids and monoglycerides are produced and incorporated into mixed micelles, which solubilize curcumin within their hydrophobic core, thereby improving its bioaccessibility [31]. Among these formulations are oil-in-water emulsions [32], microemulsions [33], solid dispersions [34], solid lipid nanoparticles [35], liposomes [36], lipid solutions and self-emulsifying drug and bioactive delivery systems (SEDDS) [37].

Emulsion-based delivery systems, particularly oil-in-water (O/W) emulsions, are very convenient for solubilizing lipophilic compounds such as curcumin. In these colloidal systems, curcumin is first solubilized within the oily phase, and then this phase is homogenized within the aqueous phase containing the emulsifier [32][35]. O/W emulsions consist of small lipid droplets coated with the emulsifier and dispersed into an aqueous phase. O/W emulsions are thermodynamically unstable systems that require high-energy emulsification methods (e.g., high-pressure homogenization, sonication, microfluidization, among others) for stabilization. A conventional O/W emulsion consists of lipid droplets with diameters greater than 200 nm. When the droplets have a diameter between 20 and 200 nm, they are called nanoemulsions. In contrast, microemulsions vary in their thermodynamic stability and can therefore be formed spontaneously by mixing their components [38].

Several studies have suggested that the use of emulsion-based delivery systems increases curcumin bioaccessibility, due to the formation of mixed micelles during lipid digestion, which in turn increases the solubility of curcumin in the intestinal fluid [4][39]. The composition and structure of these systems are specifically designed to improve curcumin bioavailability by increasing its bioaccessibility in the gastrointestinal tract [32]. For example, in emulsions and nanoemulsions, the type of lipid significantly affects the in vitro intestinal digestion of curcumin. The curcumin bioaccessibility increases in emulsions (58%) and nanoemulsions (59%), which contain medium-chain fatty acids possibly because of their higher capacity to form mixed micelles during digestion [14].

On the other hand, liposomes are vesicles that present one or more bilayers, generally formed by phospholipids, which allow them to enclose both lipid-soluble (e.g., curcumin) and water-soluble substances [36][40]. Liposomes with a variable diameter (20 to 400 nm) are obtained by forming a lipid film that is resuspended in a specific aqueous system and extruded or sonicated. Other in vitro digestion studies have concluded that curcumin bioaccessibility is increased (1.7-fold concerning the free compound) when it is contained in liposomes [34][41][42]. These results could explain why curcumin-loaded liposomes showed 4-fold higher absorption and 2.4-fold higher plasma antioxidant activity compared to free curcumin administered orally to rats (100 mg/day/kg by gavage) [40].

SEDDS are mixtures of lipids, surfactants and cosolvents that form fine O/W emulsions once dispersed into an aqueous medium under gentle agitation. In this sense, gastrointestinal tract fluids and motility provide the necessary medium and the agitation for the self-emulsification of these formulations. In this way, SEDDS form loaded emulsion droplets that increase the solubility and absorption of orally consumed hydrophobic compounds, such as curcumin [37]. SEDDS significantly increase the curcumin solubility (70–100%) compared to the free and pure compound at both neutral pH (6.8) and acidic conditions (0.1 N HCl) [37]. Results of acute preclinical studies (24 h, 25–100 mg/kg day) have shown that oral administration of curcumin-loaded SEDDS significantly increases its plasma absorption (~50–94%) by binding curcumin with the lipid fraction of the emulsion and thereby increasing its bioaccessibility [37][43].

Another suggested approach to improve the bioavailability of curcumin involves the use of bioenhancers, such as piperine. Piperine is known to enhance curcumin absorption and tissue uptake, while also reducing curcumin hepatic metabolism. Once absorbed, curcumin is metabolized within the epithelial cells and/or effluxed back into the intestinal lumen. This efflux is thought to occur due to the presence of efflux transporters within the intestinal cell membranes. Piperine from black pepper, as well as certain catechins from green tea, are able to inhibit these transporters, thus increasing the amount of curcumin that remains in the body [44].

4. Conclusions

HD significantly increases the oxidative and inflammatory parameters in patients undergoing RRT. The regular intake of natural antioxidants, as a complement to dietary therapy for CKD patients, has been shown to effectively control these biomarkers, thereby contributing to reducing the adverse effects of HD. One of the most promising bioactive compounds is curcumin, a major polyphenol in turmeric that has been successfully evaluated in the treatment of several chronic pathologies, including CKD.

Several mechanisms of action associated with the antioxidant role of curcumin have been proposed as responsible for its anti-inflammatory activity. This has been evidenced in preclinical and clinical studies where regular intake of variable doses of curcumin has been effective in controlling oxidative and inflammatory parameters. However, the most effective oral administration vehicle for curcumin has not yet been defined. Due to its physicochemical properties, the bioaccessibility and bioavailability of this compound are low. In this regard, several oral systems of controlled delivery of curcumin have been evaluated, among which liposomes and SEDDS stand out as the best at the preclinical level in terms of bioaccessibility and absorption of the bioactive compound. Likewise, oral administration of free curcumin together with adjuvants that decrease its hepatic metabolism, such as piperine, has increased its bioavailability in both rats and humans.

Future research should aim to consider the bioaccessibility of curcumin in the rational design of the administration vehicle, particularly for oral consumption, to enhance its bioavailability and ensure its effectiveness.

References

- Li, P.K.-T.; Chan, G.C.-K.; Chen, J.; Chen, H.-C.; Cheng, Y.-L.; Fan, S.L.-S.; He, J.C.; Hu, W.; Lim, W.-H.; Pei, Y.; et al. Tackling Dialysis Burden around the World: A Global Challenge. Kidney Dis. 2021, 7, 167–175

- Pat, P. Hemodiálisis y Diálisis Peritoneal. In Conceptos Básicos de Control de Infecciones; IFIC International Federation of Infection Control: Sheffield, UK, 2011; Chapter 19; pp. 289–302

- Dinarello, C.A. Cytokines: Agents Provocateurs in Hemodialysis? Kidney Int. 1992, 41, 683–694.

- He, Y.; Yue, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, K.; Chen, S.; Du, Z. Curcumin, Inflammation, and Chronic Diseases: How Are They Linked? Molecules 2015, 20, 9183–9213

- Panstw Zakl, R.; Bogacka, A.; Sobczak-Czynsz, A.; Kucharska, E.; Madaj, M.; Stucka, K. Analysis of nutrition and nutritional status of haemodialysis patients. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2018, 69, 165–174

- Hassan, K.S.; Hassan, S.K.; Hijazi, E.G.; Khazim, K.O. Effects of Omega-3 on Lipid Profile and Inflammation Markers in Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. Ren. Fail. 2010, 32, 1031–1035

- Korish, A.A.; Arafah, M.M. Catechin Combined with Vitamins C and E Ameliorates Insulin Resistance (IR) and Atherosclerotic Changes in Aged Rats with Chronic Renal Failure (CRF). Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2008, 46, 25–39

- Li, Y.; Bao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, X.; Ding, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Y. Effects of Grape Seed Proanthocyanidin Extract on Renal Injury in Type 2 Diabetic Rats. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 645–652

- Varatharajan, R.; Sattar, M.Z.A.; Chung, I.; Abdulla, M.A.; Kassim, N.M.; Abdullah, N.A. Antioxidant and Pro-Oxidant Effects of Oil Palm (Elaeis Guineensis) Leaves Extract in Experimental Diabetic Nephropathy: A Duration-Dependent Outcome. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 242

- González-Albadalejo, J.; Sanz, D.; Claramunt, R.M.; Lavandera, J.L.; Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J. Curcumin and Curcuminoids: Chemistry, Structural Studies and Biological Properties. An. Real Acad. Nac. Farm. 2015, 81, 278–310

- Kocaadam, B.; Şanlier, N. Curcumin, an Active Component of Turmeric (Curcuma Longa), and Its Effects on Health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2889–2895

- Gupta, S.C.; Patchva, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Therapeutic Roles of Curcumin: Lessons Learned from Clinical Trials. AAPS J. 2013, 15, 195–218

- Pakfetrat, M.; Basiri, F.; Malekmakan, L.; Roozbeh, J. Effects of Turmeric on Uremic Pruritus in End Stage Renal Disease Patients: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Nephrol. 2014, 27, 203–207

- Samadian, F.; Dalili, N.; Poor -reza Gholi, F.; Fattah, M.; Malih, N.; Nafar, M.; Firoozan, A.; Ahmadpoor, P.; Samavat, S.; Ziaie, S. Evaluation of Curcumin’s Effect on Inflammation in Hemodialysis Patients. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2017, 22, 19–23

- Sun, D.; Zhuang, X.; Xiang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, C.; Barnes, S.; Grizzle, W.; Miller, D.; Zhang, H.G. A Novel Nanoparticle Drug Delivery System: The Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Curcumin Is Enhanced When Encapsulated in Exosomes. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 1606–1614

- Rao, C.V. Regulation of Cox and Lox by Curcumin. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2007, 595, 213–226

- Alvarenga, L.; Cardozo, L.F.M.F.; Da Cruz, B.O.; Paiva, B.R.; Fouque, D.; Mafra, D. Curcumin Supplementation Improves Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Biomarkers in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2022, 54, 2645–2652

- Ghosh, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Rashid, K.; Sil, P.C. Curcumin Protects Rat Liver from Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Pathophysiology by Counteracting Reactive Oxygen Species and Inhibiting the Activation of P53 and MAPKs Mediated Stress Response Pathways. Toxicol. Rep. 2015, 2, 365–376

- El-Gizawy, M.M.; Hosny, E.N.; Mourad, H.H.; Abd-El Razik, A.N. Curcumin Nanoparticles Ameliorate Hepatotoxicity and Nephrotoxicity Induced by Cisplatin in Rats. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2020, 393, 1941–1953

- Soetikno, V.; Sari, F.R.; Lakshmanan, A.P.; Arumugam, S.; Harima, M.; Suzuki, K.; Kawachi, H.; Watanabe, K. Curcumin Alleviates Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Renal Fibrosis in Remnant Kidney through the Nrf2-Keap1 Pathway. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 1649–1659

- Zhang, J.; Tang, L.; Li, G.S.; Wang, J. The Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Curcumin on Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Ren. Fail. 2018, 40, 680–686

- Soetikno, V.; Sari, F.R.; Veeraveedu, P.T.; Thandavarayan, R.A.; Harima, M.; Sukumaran, V.; Lakshmanan, A.P.; Suzuki, K.; Kawachi, H.; Watanabe, K. Curcumin Ameliorates Macrophage Infiltration by Inhibiting NF-B Activation and Proinflammatory Cytokines in Streptozotocin Induced-Diabetic Nephropathy. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 8, 1–11

- Ueki, M.; Ueno, M.; Morishita, J.; Maekawa, N. Curcumin Ameliorates Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity by Inhibiting Renal Inflammation in Mice. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2013, 115, 547–551

- Menon, V.P.; Sudheer, A.R. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Curcumin. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2007, 595, 105–125

- Alvarenga, L.; Salarolli, R.; Cardozo, L.F.M.F.; Santos, R.S.; de Brito, J.S.; Kemp, J.A.; Reis, D.; de Paiva, B.R.; Stenvinkel, P.; Lindholm, B.; et al. Impact of Curcumin Supplementation on Expression of Inflammatory Transcription Factors in Hemodialysis Patients: A Pilot Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Study. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 3594–3600

- Salarolli, R.T.; Alvarenga, L.; Cardozo, L.F.M.F.; Teixeira, K.T.R.; de Moreira, L.S.G.; Lima, J.D.; Rodrigues, S.D.; Nakao, L.S.; Fouque, D.; Mafra, D. Can Curcumin Supplementation Reduce Plasma Levels of Gut-Derived Uremic Toxins in Hemodialysis Patients? A Pilot Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2021, 53, 1231–1238

- Vafadar Afshar, G.; Rasmi, Y.; Yagmaye, P.; Khadem-Ansari, M.-H.; Makhdomi, K.; Rasooli, J. The Effects of Nano-Curcumin Supplementation on Serum Level of Hs-CRP, Adhesion Molecules, and Lipid Profiles in Hemodialysis Patients, A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 14, 52

- Seddik, A.A. The Effect of Turmeric and Ginger on Oxidative Modulation in End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Patients. Int. J. Adv. Res. (IJAR) 2015, 3, 657–670

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Refined Exposure Assessment for Curcumin (E 100). EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3876

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Newman, R.A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Bioavailability of Curcumin: Problems and Promises. Mol. Pharm. 2007, 4, 807–818

- Faridi Esfanjani, A.; Assadpour, E.; Jafari, S.M. Improving the Bioavailability of Phenolic Compounds by Loading Them within Lipid-Based Nanocarriers. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 76, 56–66

- McClements, D.J.; Rao, J. Food-Grade Nanoemulsions: Formulation, Fabrication, Properties, Performance, Biological Fate, and Potential Toxicity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 285–330

- Wu, X.; Xu, J.; Huang, X.; Wen, C. Self-Microemulsifying Drug Delivery System Improves Curcumin Dissolution and Bioavailability. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2011, 37, 15–23

- De Leo, V.; Milano, F.; Mancini, E.; Comparelli, R.; Giotta, L.; Nacci, A.; Longobardi, F.; Garbetta, A.; Agostiano, A.; Catucci, L. Encapsulation of Curcumin-Loaded Liposomes for Colonic Drug Delivery in a PH-Responsive Polymer Cluster Using a PH-Driven and Organic Solvent-Free Process. Molecules 2018, 23, 739

- McClements, D.J.; Xiao, H. Designing Food Structure and Composition to Enhance Nutraceutical Bioactivity to Support Cancer Inhibition. In Seminars in Cancer Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 46, pp. 215–226

- McClements, D.J. Encapsulation, Protection, and Release of Hydrophilic Active Components: Potential and Limitations of Colloidal Delivery Systems. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 219, 27–53

- Yan, Y.D.; Kim, J.; Kwak, M.K.; Yoo, B.K.; Yong, C.S.; Choi, H.G. Enhanced Oral Bioaccessibility of Curcumin via a Solid Lipid-Based Self-Emulsifying Drug System Using a Spray Drying Technique. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 34, 1179–1186

- Mason, T.G.; Wilking, J.N.; Meleson, K.; Chang, C.B.; Graves, S.M. Nanoemulsions: Formation, Structure, and Physical Properties. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2006, 18, R635

- Cui, F.; Han, S.; Wang, J.; McClements, D.J.; Liu, X.; Liu, F. Co-Delivery of Curcumin and Epigallocatechin Gallate in W/O/W Emulsions Stabilized by Protein Fibril-Cellulose Complexes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2023, 222, 113072

- Takahashi, M.; Uechi, S.; Takara, K.; Asikin, Y.; Wada, K. Evaluation of an Oral Carrier System in Rats: Bioavailability and Antioxidant Properties of Liposome-Encapsulated Curcumin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 9141–9146

- Cheng, C.; Peng, S.; Li, Z.; Zou, L.; Liu, W.; Liu, C. Improved Bioavailability of Curcumin in Liposomes Prepared Using a PH-Driven, Organic Solvent-Free, Easily Scalable Process. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 25978–25986

- Gómez-Mascaraque, L.G.; Casagrande Sipoli, C.; de La Torre, L.G.; López-Rubio, A. Microencapsulation Structures Based on Protein-Coated Liposomes Obtained through Electrospraying for the Stabilization and Improved Bioaccessibility of Curcumin. Food Chem. 2017, 233, 343–350

- Dhumal, D.M.; Kothari, P.R.; Kalhapure, R.S.; Akamanchi, K.G. Self-Microemulsifying Drug Delivery System of Curcumin with Enhanced Solubility and Bioavailability Using a New Semi-Synthetic Bicephalous Heterolipid: In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 90295–90306

- Zeng, X.; Cai, D.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhong, G.; Zhuo, J.; Gan, H.; Huang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Yao, N.; et al. Selective Reduction in the Expression of UGTs and SULTs, a Novel Mechanism by Which Piperine Enhances the Bioavailability of Curcumin in Rat. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2017, 38, 3–19

More