Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Conner Chen and Version 1 by Sara Hashish.

Parkinson’s disease is a debilitating multisystemic disorder affecting both the central and peripheral nervous systems. Accumulating evidence suggests a potential interaction between gut microbiota and the pathophysiology of the disease. As a result of the degradation of dopaminergic neurons, PD patients develop motor impairments such as tremors, rigidity, and slowness of movement. These motor features are preceded by gastrointestinal issues, including constipation. Given these gastrointestinal issues, the gut has emerged as a potential modulator of the neurodegenerative cascade of PD.

- Parkinson’s disease

- gut–brain axis

- dysbiosis

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder after Alzheimer’s [1]. It predominantly impacts the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra (SN) in the midbrain region, resulting in a decline in dopamine levels and motor impairments, including resting tremors, slowness of movement, gait disturbance, rigidity, balance issues, and akinesia. PD is not only characterized by motor and cognitive impairments but also the associated non-motor and gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms that often start to markedly manifest years or decades before the classical motor features [2]. The non-motor characteristics include constipation, dry mouth, prolonged intestinal transit time, or defecation-associated dysfunctions alongside other symptoms such as sleeping disruption, olfactory dysfunction, and depression [3]. PD is thus presumed to be a multi-systemic disease, influencing both the central and peripheral nervous systems. While the disease is in its prodromal stage, most of the non-motor symptoms are overlooked. Diagnosis and treatment begin only when the motor symptoms surface; by then, more than fifty percent of the dopaminergic neurons of the SN might have been lost [4]. Ever since the end of the prologue to PD in an observational essay on the “shaky Palsy” by James Parkinson two centuries ago, investigations to detect the trigger that progresses PD have been central [5]. The intracellular deposition of alpha-synuclein aggregates, which induce cell death and neuroinflammation, is the most widely accepted theory underlying PD pathogenesis [6]. Since Lewy uncovered the eosinophilic inclusion body and established the contribution of alpha-synucleinopathy, researchers have been interested in unravelling other aspects of the pathophysiology of PD and in highlighting the multiple factors involved in its incidence. Environmental factors such as pesticide and insecticide exposure, xenobiotic toxins, genetic predispositions, aging, disrupted dopamine metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation all play a role in the onset of PD [7]. The connection between PD and the GI system has long been established following Braak’s hypothesis [8] that non-familial forms of PD are initiated in the gut by a pathogen. Braak’s hypothesis is gaining intense support, and efforts have been carried out to disclose this potential cross-talk. In PD patients, alpha-synuclein pathology has been spotted in the gut at early stages [9]. In addition, imaging studies have revealed that in some cases of pathology, PD may propagate in the gut and spread to the brain [10]. In line with these findings, alpha-synuclein pathology migrated from the gut to the brain upon the injection of alpha-synuclein fibrils into the GITs of mice [11]. Large epidemiological studies have consistently found that people who had complete truncal vagotomies decades ago were less likely to develop PD later in life [9]. An imbalance in the gut’s microbial profile may thus lead to increased susceptibility to PD.

2. Gut–Microbiota–Brain Axis

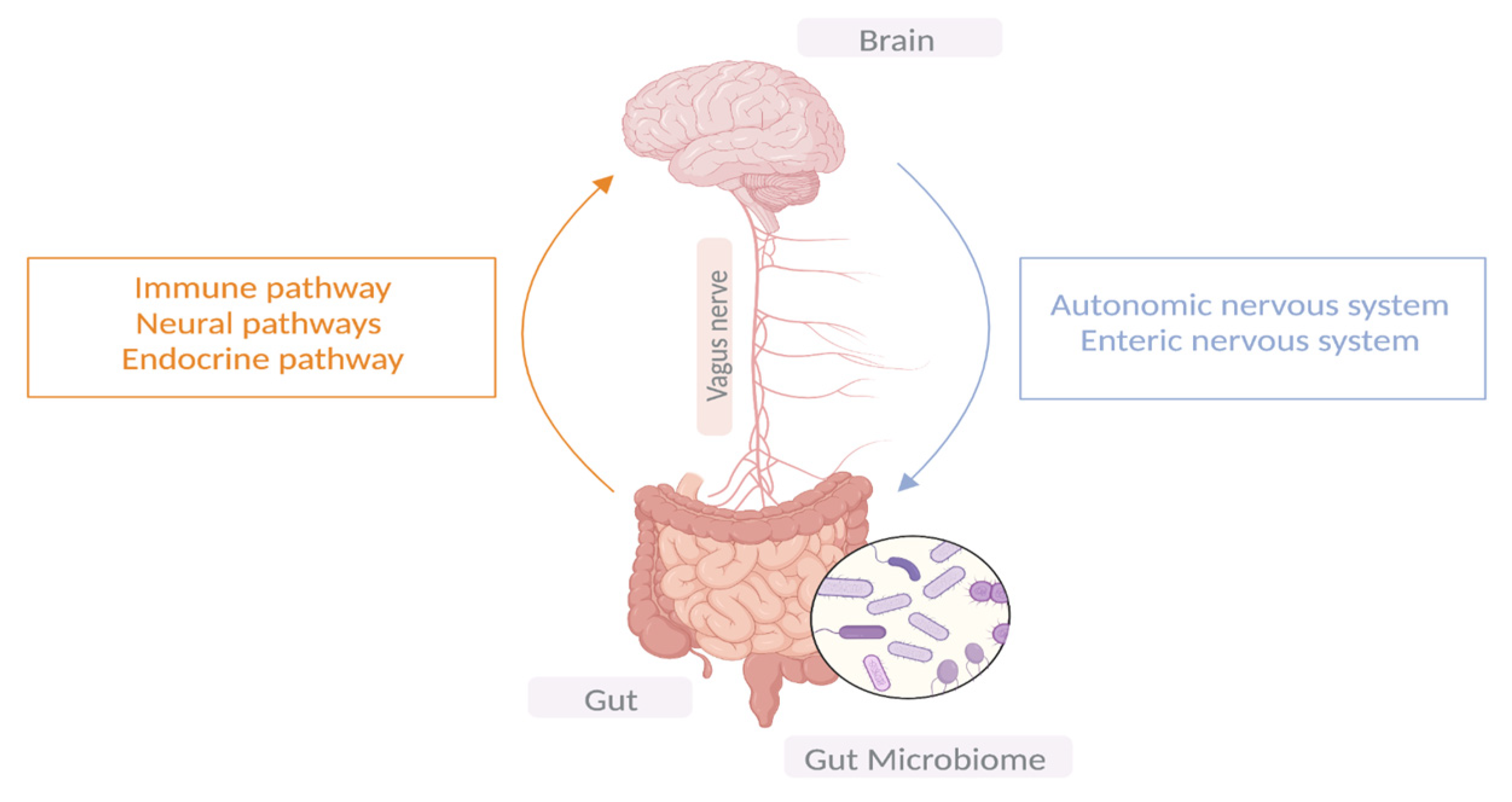

Ever since the establishment of Braak’s hypothesis that synucleinopathy may propagate in the enteric nerves of the gut before ascending to the brain via the vagus nerve and given the early GI symptoms experienced in patients with PD, researchers have been shedding light on the role the gut microbiota plays in PD pathogenesis; hence, the term “gut-brain-axis” has emerged [12]. The microbiome consists of bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea, protozoa, and bacteriophages. Microbial communities differ in composition and diversity depending on where they are located [4]. The human gut is home to microbial organisms, the majority of which encode more unique genes than the human genome. Unless there is a noticeable change in dietary habits, the gut microbial diversity remains mostly stable in an individual through adulthood. A dynamic shift in the gut microbial environment points towards a deteriorating immune system and its associated health consequences [13]. Emerging evidence suggests bidirectional communication between the GI tract and the brain via the central vagal nerve and systemic metabolic routes. Similarly, microbiota–gut–brain bidirectional interactions take place through neuronal, immunomodulatory, humoral, and endocrine networks [14]. It is noteworthy that the ENS innervates the GI system, and its proximity to the intestinal lumen creates an opportunity for a remarkable connection with gut microbiota. Therefore, the gut–brain axis is made up of three hubs: the brain connectome, the gut connectome, and its microbiome (Figure 1). All the hubs communicate with each other via bidirectional connections with multiple feedback loops, creating a non-linear system [15], while the CNS can directly impact the function and composition of the gut microbiota through the autonomic nervous system [16].

Figure 1.

The bidirectional communication between the central nervous system and the GIT.

3. Gut Microbiota Disparities in PD Patients vs. Controls

Several studies have been performed in diverse populations worldwide. These studies have followed different methodologies; some employed untargeted sequencing techniques (shotgun metagenomics); others relied on a targeted approach and sequenced the 16S rRNA region; and others went for a more classical approach and performed qPCR in an effort to dissect the relative abundance of bacterial taxa in patients with PD compared to their healthy counterparts [4]. Disparities at the microbial level have been reported between PD patients and healthy controls. In 2015, researchers in Finland analyzed the fecal microbiome of 72 PD patients and 72 control subjects by pyrosequencing the V1–V3 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. Their results showed that the prevalence of Prevotellaceae in PD patients decreased by 77.6% as compared with the controls. Furthermore, a logistic regression classifier based on the abundance of four bacterial families and the severity of constipation identified PD patients with 66.7% sensitivity and 90.3% specificity. In addition, the relative abundance of Enterobacteriaceae was positively linked to the severity of postural instability and gait difficulty [17]. In 2019, Aho and colleagues conducted another study in Finland to further differentiate the gut microbiota of PD patients and the controls. They found significant differences between microbial species in PD patients and the controls, but not between time points. The reported bacterial taxa that varied between the two groups included Roseburia, Prevotella, and Bifidobacterium [18]. Aho et al. further compared the bacterial composition of stable PD patients with that of those with faster disease progression. The findings showed inconsistent taxa abundance across methods and time points; however, different distributions of enterotypes and a declining abundance of Prevotella were observed in faster-progressing patients [18]. This study intriguingly demonstrates that some bacterial taxa might be linked to disease severity and progression. Though both studies involved a Finnish population, the outcomes were inconsistent, highlighting the dynamic nature of the gut microbiome and the several factors that shape it. Another study was conducted in a northern German cohort in 2017 and reported significant differences between PD subjects and the controls for four bacterial families; Lactobacillaceae were more abundant in the PD cases. A higher abundance of Barnesiellaceae and Enterococcaceae was also observed in the PD cases in this research but not in other studies [19]. Following Hopfiner, Heintz-Buschart et al. [20] characterized the microbial taxa in PD and its prodrome, idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, in comparison to healthy controls. Differentially abundant gut pathogens, such as Akkermansia, were present in PD subjects. Additionally, 80% of the differential gut bacterial communities in PD subjects versus the healthy controls reflected similar patterns in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder [20]. In another case–control study conducted on a German cohort, Weis et al. [21] found a relative decrease in the bacterial taxa linked to health-promoting, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective effects, such as Faecalibacterium and Fusicatenibacter. Both taxa were less abundant in PD patients, along with increased levels of the fecal inflammation marker calprotectin. Furthermore, the Clostridiales family XI and their affiliated members were found to be overrepresented in PD patients. Interestingly, Weis et al. took a step forward and investigated the potential impact of PD medications (i.e., Levodopa and Entacapone) on the gut microbiota composition. The relative representation of the microbial genera Peptoniphilus, Finegoldia, Faecalibacterium, Fusicatenibacter, Anaerococcus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, and Ruminococcus were markedly influenced by the PD medications [21]. Weis and colleagues captivatingly brought up the host microbiome–drug interaction in PD patients and the potential influence of PD medications on the gut microbiome, which needs to be addressed in future research. Similar studies were performed across other populations in efforts to identify disease-specific bacteria and deepen our understanding of the role of altered gut microbiota in PD pathogenesis. In the US, Keshavarzian, A. et al. [22] have investigated the colonic bacteria in both PD and control subjects. Their research showed that putative, “anti-inflammatory” butyrate-producing bacteria from the genera Blautia, Coprococcus, and Roseburia were significantly less abundant in the feces of PD patients than the controls, while putative “proinflammatory” proteobacteria of the genus Ralstonia were significantly more abundant in the mucosa of the PD subjects than in the controls. Bacteria from the genus Faecalibacterium were significantly more abundant in the mucosa of the controls than the PD subjects. In 2017, researchers in the US found a significantly disrupted abundance of Bifidobacteriaceae, Christensenellaceae, Tissierellaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Lactobacillaceae, Pasteurellaceae, and Verrucomicrobiaceae families among PD patients as compared to the controls [23]. In 2018, a case–control study was conducted to explore the fecal microbiota composition in Chinese PD patients. The structure and richness of the fecal microbiota varied between PD patients and healthy controls. The genera Clostridium IV, Aquabacterium, Holdemania, Sphingomonas, Clostridium XVIII, Butyricicoccus, and Anaerotruncus were overabundant in PD patients [24], while in northeast China, Li et al. documented a remarkably altered abundance in various taxa in PD cases compared to the controls, and an elevation in Akkermansia and a decrease in Lactobacillus in the PD patients were observed [25]. Studies have continued to emerge in different regions to decipher the interplay between gut microbiota and neurodegeneration in PD. In a Russian population, Petrov et al. [26] analyzed the gut microbiota of people with PD and healthy controls using the method of high throughput 16S rRNA sequencing of bacterial genomes. The findings in the patients with PD revealed a reduced content of Dorea, Bacteroides, Prevotella, Faecalibacterium, Bacteroides massiliensis, Stoquefichusmassiliensis, Bacteroides coprocola, Blautiaglucerasea, Dorealongicatena, Bacteroides dorei, Bacteroides plebeus, Prevotella copri, Coprococcuseutactus, and Ruminococcuscallidus, while a higher abundance of Christensenella, Catabacter, Lactobacillus, Oscillospira, Bifidobacterium, Christensenellaminuta, Catabacterhongkongensis, Lactobacillus mucosae, Ruminococcus bromii, and Papillibactercinnamivorans was observed [26]. Data on the microbiota composition of Italian PD patients were also described. The PD patients were enriched with the Lactobacillaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Enterococcaceae families compared to the healthy controls, while Lachnospiraceae were significantly lowered [27]. Interestingly, a large-scale metagenomic study adopting a high taxonomic resolution was recently conducted to discern the role of the gut microbiome in PD. Wallen et al.’s results aligned with the existing literature and resolved the inconsistencies imposed by previous studies [28]. The species included Blautia, Faecalibacterium, Fusicatenibacter, Roseburia, and Ruminococcus, which are reduced in PD, and Bifidobacterium, Hungatella, Lactobacillus, Methanobrevibacter, and Porphyromonas, which are elevated in PD [2,29,30][2][29][30]. Prevotella has been reported as being depleted in PD by some [17,26][17][26] and as increased by others [23,31][23][31]. At the species level, Prevotella copri was decreased, and the pathogenic species of Prevotella were increased as a group, confirming the seemingly contradictory reports on Prevotella. Although most studies report elevated Akkermansia in PD patients, Wallen and colleagues described it as a “conundrum”, as they did not detect a statistically significant trend for Akkermansia at the genus or species level in their southern US cohort, suggesting a geographic effect [28]. This finding intriguingly emphasizes that the gut microbiome is influenced by geographic locations and that populations living in different areas might be carrying unique bacterial fingerprints. In a meta-analysis study of five 16S rRNA gene sequencing datasets, Nishiwaki et al. reported that intestinal mucin layer-degrading Akkermansia is elevated and that short-chain fatty acid-producing Roseburia and Faecalibacterium are decreased in PD across countries [29]. Extending the work of Nishiwaki et al., Romano and colleagues conducted another meta-analysis study of ten currently available 16S microbiome datasets to further investigate whether common alterations in the gut microbiota of PD patients exist across cohorts. The enrichment of the genera Lactobacillus, Akkermansia, and Bifidobacterium and the depletion of bacteria affiliated with the Lachnospiraceae family and the Faecalibacterium genus were documented [2]. Several studies have therefore capitalized on the changes in the microbial profile in patients with PD; however, extensive research is required to identify those disease-specific bacteria that might serve as robust markers to slow the progression of the disease.4. Dysbiosis and PD Clinical Features

With growing evidence implicating the gut in PD pathogenesis and a growing appreciation for the role of gut microbiota in PD and other chronic diseases, there has been an upward trend in decoding the interplay between gut microbiota composition and PD clinical properties. Several studies demonstrated an association between dysbiosis and (1) intestinal inflammation and barrier dysfunction, (2) disease duration, (3) motor symptoms, and (4) non-motor symptoms, which is consistent with the current findings.4.1. Microbiota Associated with Barrier Dysfunction and Gut Intestinal Inflammation

The GI tract is lined with an intestinal mucosa, which serves as a physical and immunological barrier between the environment and the internal host. This mucosa surrounds the blood circulation, which is semipermeable and crucial for nutrient uptake [4]. Microorganisms inhabiting the gut alongside their metabolic by-products are the major factors that contribute to an impaired intestinal barrier and hyperpermeability through a metabolic profile shift induced by dysbiosis, bringing about the so-called “leaky gut” and inflammation. When thrown off balance, gut-related pathogens can alter the tight junction, disrupt the permeability, and relocate via Peyer’s patches [32]. This dysbiosis and increased permeability trigger, in turn, an intestinal inflammatory response and the secretion of proinflammatory markers that may penetrate the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and act on neurons and glial cells, eliciting neuroinflammation and cell death. This has been hypothesized to be associated with lowered levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), signaling molecules that play a significant role in sustaining the integrity of the colonic epithelium [2]. SCFAs also have immunomodulatory functions and provoke anti-inflammatory activity via increasing and/or activating regulatory T cells [33]. A low abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria among PD patients can explain the decreased levels of SCFAs. Prevotella, Faecalibacterium, Blautia, and Roseburia were found to be depleted in PD subjects across multiple studies [18[18][23][34][35][36],23,34,35,36], whereas Enterococcaceae were overrepresented; Enterococcaceae are presumed to possibly lower the production of SCFA and secrete endotoxins and neurotoxins that promote intestinal inflammation [4]. This decreased abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria may further generate a neuroinflammatory response, which subsequently leads to the recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms affecting patients with PD. The phylum Verrucomicrobia (Akkermansia) has also been widely reported to be remarkably present in PD patients in various studies [23,37,38][23][37][38]. Akkermansia feeds on the intestinal mucin and degrades it into SCFA acetate, a substrate for other crucial bacteria to synthesize butyrate, which is an energy source for epithelial cells of the gut [39]. Additionally, Akkermansia enhances mucosal integrity and regulates the immune system. If the intestinal epithelium fails to compensate for the mucin utilized by Akkermansia, detrimental effects such as leaky gut and inflammation will arise [4]. In addition to the deficiency in SCFA-generating bacteria with anti-inflammatory properties in PD patients, an increased abundance of proinflammatory pathobionts of the phylum Proteobacteria was reported in PD patients [22]. Dysbiosis may thus result in a proinflammatory status. This triggered local inflammation could be linked to alpha-synucleinopathy. Dysbiosis and exposure to bacterial endotoxin, according to Forsyth et al. [32], may promote alpha-synuclein misfolding by inducing GI inflammation and hyperpermeability in PD patients. Together, these observations highlight the fact that dysbiosis disrupts the integrity of the GIT, eliciting an immune reaction that triggers the neurovegetative cascade of PD.4.2. Duration of Disease, Motor Symptoms, and Associated Microbiota

Various studies have reported a link between the abundance of certain bacterial taxa and disease duration. Keshavarzian et al. [22] proposed that PD duration increases the abundance of the phylum Proteobacteria while decreasing the abundance of Firmicutes. Keshavarzian and colleagues, with findings that were consistent with those of another study by Hill-Burns et al., reported a negative correlation between Lachnospiraceae and duration [23]. Later, Barichella et al. discovered that the duration of the disease influenced the gut microbiota, with enriched levels of Lachnospiraceae and a co-abundant genus Akkermansia [40]. Researchers have continued to unfold this potential association between gut commensals and PD duration. In 2015, Hasegawa et al. suggested that an elevated level in the Lactobacillus gasseri subgroup may predict disease duration in PD [41]. Intriguingly, the microbial composition at an early disease onset might be different to that at a late onset. Lin et al. observed that Pasteurellaceae, Alcaligenaceae, and Fusobacteria were more abundant in the early onset of PD, whereas Comamonas and Anaerotruncus were present in the late onset of the disease [42]. Similarly, Hill-Burns described an increased Ruminococcaceae in patients with the disease for more than ten years, unlike patients within the first ten years of the disease who showed less Ruminococcaceae abundance [23]. In conjunction with the currently known research, the gut commensals may be used as markers to detect the disease stage, as each stage might present its own unique microbial makeup. Studies have also investigated the variation in microbial patterns with respect to motor symptoms experienced by PD patients. For example, particular gut-related pathogens, such as Aquabacterium, Peptococcus, and Sphingomonas, have been found to be associated with motor complications in PD [24]. Microbiota signatures may also discriminate between tremor-dominant and non-tremor PD patients. In tremor-dominant subjects, Roseburia [42], Flavobacterium, Bacteroidia, Propionibacterium, and Alcaligenaceae [43] are abundant, while Leptotrichia [42], Clostridium, Verrucomicrobia, and Akkermansia [43] are abundant in non-tremor PD subjects. A decreased abundance of the family Ruminococcaceae was noted in PD patients with tremors [21]. Bacteria associated with other motor difficulties have also been observed. Lactobacillaceae [40] and Enterobacteriaceae [17,27,42][17][27][42] are associated with postural instability and gait disturbance in PD, but there is also a decreased representation of Lachnospiraceae [40]. Prevotella is another promising bacterial marker that has been extensively studied in correlation with PD clinical phenotypes as well as disease progression. Several studies have shown a decreased abundance of Prevotella in PD patients with postural instability and gait difficulty compared to the controls [17,18,27,44][17][18][27][44]. Although several studies attribute the clinical characteristics of PD to a deviated microbial profile, future research is warranted to provide a mechanistic interpretation and to enhance our understanding of the gut microbiota and brain interactions.4.3. Microbiota and Non-Motor Symptoms

The prodromal non-motor features, such as anosmia, depression, sleep disorders, and constipation, have been linked to an altered gut microbiota. According to Qian et al. [24] a decrease in Bifidobacterium abundance is linked to depression. While Barichella et al. [40] proposed a possible link between intellectual impairment and an increased abundance of Lactobacilli and a decreased abundance of Lachnospiraceae. In a more recent study, Ren et al. assessed cognitive decline using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) questionnaires. The genera Alistipes and Odoribatcer were found to be negatively correlated with MoCA scores. Barnesiella is negatively associated with MMSE scores. Butyricimonas have been negatively associated with MMSE and MoCA scores. The genus Blautia of the family Lachnospiraceae was noted to be depleted in patients with mild cognitive impairment, whereas an enriched abundance of the families Rikenellaceae and Ruminococcaceae was reported [45]. Constipation is presumed to be one of the most common GI-associated symptoms and is reported in approximately 60% of patients with PD [4]. Research has indicated that dysbiosis may contribute to GI dysfunction and constipation at an early stage of PD pathogenesis, with an increase in Lactobacillaceae [30], Verrucomicrobiaceae, Bradyrhizobiaceae [17], Bifidobacterium [46], and Akkermansia [20,37,46][20][37][46]. Akkermansia has been associated with slow transit time [20[20][46],46], firmness of stool [37], and constipation severity [36]. The association between a deviated gut microbiota and the non-motor symptoms characterizing PD is becoming more evident, and these findings should open new avenues for research to better understand the exact mechanisms by which the gut bacteria contribute to PD-associated symptoms.References

- Elbaz, A.; Carcaillon, L.; Kab, S.; Moisan, F. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Rev. Neurol. 2016, 172, 14–26.

- Romano, S.; Savva, G.M.; Bedarf, J.R.; Charles, I.G.; Hildebrand, F.; Narbad, A. Meta-analysis of the Parkinson’s disease gut microbiome suggests alterations linked to intestinal inflammation. NPJ Park. Dis. 2021, 7, 27.

- Fasano, A.; Bove, F.; Gabrielli, M.; Petracca, M.; Zocco, M.A.; Ragazzoni, E.; Barbaro, F.; Piano, C.; Fortuna, S.; Tortora, A.; et al. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 1241–1249.

- Pavan, S.; Prabhu, A.N.; Gorthi, S.P.; Das, B.; Mutreja, A.; Shetty, V.; Ramamurthy, T.; Ballal, M. Exploring the multifactorial aspects of Gut Microbiome in Parkinson’s Disease. Folia Microbiol. 2022, 67, 693–706.

- Parkinson, J. An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. J. Neuropsychiatry 2002, 14, 223–236.

- Keshavarzian, A.; Engen, P.; Bonvegna, S.; Cilia, R. The gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease: A culprit or a bystander? In Progress in Brain Research; Recent Advances in Parkinson’s Disease; Björklund, A., Cenci, M.A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Chapter 11; pp. 357–450.

- Riess, O.; Krüger, R. Parkinson’s disease—A multifactorial neurodegenerative disorder. In Diagnosis and Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease—State of the Art; Journal of Neural Transmission. Supplementa; Przuntek, H., Müller, T., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1999; pp. 113–125.

- Braak, H.; Rüb, U.; Gai, W.P.; Del Tredici, K. Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: Possible routes by which vulnerable neuronal types may be subject to neuroinvasion by an unknown pathogen. J. Neural. Transm. 2003, 110, 517–536.

- Breen, D.P.; Halliday, G.M.; Lang, A.E. Gut–brain axis and the spread of α-synuclein pathology: Vagal highway or dead end? Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 307–316.

- Horsager, J.; Andersen, K.B.; Knudsen, K.; Skjærbæk, C.; Fedorova, T.D.; Okkels, N.; Schaeffer, E.; Bonkat, S.K.; Geday, J.; Otto, M.; et al. Brain-first versus body-first Parkinson’s disease: A multimodal imaging case-control study. Brain 2020, 143, 3077–3088.

- Kim, S.; Kwon, S.-H.; Kam, T.-I.; Panicker, N.; Karuppagounder, S.S.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, W.R.; Kook, M.; Foss, C.A.; et al. Transneuronal Propagation of Pathologic α-Synuclein from the Gut to the Brain Models Parkinson’s Disease. Neuron 2019, 103, 627–641.

- Rietdijk, C.D.; Perez-Pardo, P.; Garssen, J.; Van Wezel, R.J.A.; Kraneveld, A.D. Exploring Braak’s Hypothesis of Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 37.

- Ley, R.E.; Peterson, D.A.; Gordon, J.I. Ecological and Evolutionary Forces Shaping Microbial Diversity in the Human Intestine. Cell 2006, 124, 837–848.

- Osadchiy, V.; Martin, C.R.; Mayer, E.A. Gut Microbiome and Modulation of CNS Function. Compr. Physiol. 2019, 10, 57–72.

- Horn, J.; Mayer, D.E.; Chen, S.; Mayer, E.A. Role of diet and its effects on the gut microbiome in the pathophysiology of mental disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 164.

- Mayer, E.A. Gut feelings: The emerging biology of gut–brain communication. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 453–466.

- Scheperjans, F.; Aho, V.; Pereira, P.A.B.; Koskinen, K.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Haapaniemi, E.; Kaakkola, S.; Eerola-Rautio, J.; Pohja, M.; et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 350–358.

- Aho, V.T.E.; Pereira, P.A.B.; Voutilainen, S.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Auvinen, P.; Scheperjans, F. Gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease: Temporal stability and relations to disease progression. EBioMedicine 2019, 44, 691–707.

- Hopfner, F.; Künstner, A.; Müller, S.H.; Künzel, S.; Zeuner, K.E.; Margraf, N.G.; Deuschl, G.; Baines, J.F.; Kuhlenbäumer, G. Gut microbiota in Parkinson disease in a northern German cohort. Brain Res. 2017, 1667, 41–45.

- Heintz-Buschart, A.; Pandey, U.; Wicke, T.; Sixel-Döring, F.; Janzen, A.; Sittig-Wiegand, E.; Trenkwalder, C.; Oertel, W.H.; Mollenhauer, B.; Wilmes, P. The nasal and gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease and idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 88–98.

- Weis, S.; Schwiertz, A.; Unger, M.M.; Becker, A.; Faßbender, K.; Ratering, S.; Kohl, M.; Schnell, S.; Schäfer, K.-H.; Egert, M. Effect of Parkinson’s disease and related medications on the composition of the fecal bacterial microbiota. NPJ Park. Dis. 2019, 5, 28.

- Keshavarzian, A.; Green, S.J.; Engen, P.A.; Voigt, R.M.; Naqib, A.; Forsyth, C.B.; Mutlu, E.; Shannon, K.M. Colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1351–1360.

- Hill-Burns, E.M.; Debelius, J.W.; Morton, J.T.; Wissemann, W.T.; Lewis, M.R.; Wallen, Z.D.; Peddada, S.D.; Factor, S.A.; Molho, E.; Zabetian, C.P.; et al. Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease medications have distinct signatures of the gut microbiome. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 739–749.

- Qian, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Wu, C.; Song, Y.; Qin, N.; Chen, S.-D.; Xiao, Q. Alteration of the fecal microbiota in Chinese patients with Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018, 70, 194–202.

- Li, W.; Wu, X.; Hu, X.; Wang, T.; Liang, S.; Duan, Y.; Jin, F.; Qin, B. Structural changes of gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease and its correlation with clinical features. Sci. China Life Sci. 2017, 60, 1223–1233.

- Petrov, V.A.; Saltykova, I.V.; Zhukova, I.A.; Alifirova, V.M.; Zhukova, N.G.; Dorofeeva, Y.B.; Tyakht, A.V.; Kovarsky, B.A.; Alekseev, D.G.; Kostryukova, E.S.; et al. Analysis of Gut Microbiota in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 162, 734–737.

- Pietrucci, D.; Cerroni, R.; Unida, V.; Farcomeni, A.; Pierantozzi, M.; Mercuri, N.B.; Biocca, S.; Stefani, A.; Desideri, A. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in a selected population of Parkinson’s patients. Park. Relat. Disord. 2019, 65, 124–130.

- Wallen, Z.D.; Appah, M.; Dean, M.N.; Sesler, C.L.; Factor, S.A.; Molho, E.; Zabetian, C.P.; Standaert, D.G.; Payami, H. Characterizing dysbiosis of gut microbiome in PD: Evidence for overabundance of opportunistic pathogens. NPJ Park. Dis. 2020, 6, 11.

- Toh, T.S.; Chong, C.W.; Lim, S.Y.; Bowman, J.; Cirstea, M.; Lin, C.H.; Chen, C.C.; Appel-Cresswell, S.; Finlay, B.B.; Tan, A.H. Gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease: New insights from meta-analysis. Park. Relat. Disord. 2022, 94, 1–9.

- Nishiwaki, H.; Ito, M.; Ishida, T.; Hamaguchi, T.; Maeda, T.; Kashihara, K.; Tsuboi, Y.; Ueyama, J.; Shimamura, T.; Mori, H.; et al. Meta-Analysis of Gut Dysbiosis in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 1626–1635.

- Wallen, Z.D.; Demirkan, A.; Twa, G.; Cohen, G.; Dean, M.N.; Standaert, D.G.; Sampson, T.R.; Payami, H. Metagenomics of Parkinson’s disease implicates the gut microbiome in multiple disease mechanisms. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6958.

- Forsyth, C.B.; Shannon, K.M.; Kordower, J.H.; Voigt, R.M.; Shaikh, M.; Jaglin, J.A.; Estes, J.D.; Dodiya, H.B.; Keshavarzian, A. Increased intestinal permeability correlates with sigmoid mucosa alpha-synuclein staining and endotoxin exposure markers in early Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28032.

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345.

- Li, C.; Cui, L.; Yang, Y.; Miao, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Cui, G.; Zhang, Y. Gut Microbiota Differs Between Parkinson’s Disease Patients and Healthy Controls in Northeast China. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 12, 171.

- Cosma-Grigorov, A.; Meixner, H.; Mrochen, A.; Wirtz, S.; Winkler, J.; Marxreiter, F. Changes in Gastrointestinal Microbiome Composition in PD: A Pivotal Role of Covariates. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 1041.

- Lubomski, M.; Xu, X.; Holmes, A.J.; Yang, J.Y.H.; Sue, C.M.; Davis, R.L. The impact of device-assisted therapies on the gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 780–795.

- Cirstea, M.S.; Yu, A.C.; Golz, E.; Sundvick, K.; Kliger, D.; Bsc, N.R.; Foulger, L.H.; MacKenzie, M.; Huan, T.; Finlay, B.B.; et al. Microbiota Composition and Metabolism Are Associated With Gut Function in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 1208–1217.

- Vidal-Martinez, G.; Chin, B.; Camarillo, C.; Herrera, G.V.; Yang, B.; Sarosiek, I.; Perez, R.G. A Pilot Microbiota Study in Parkinson’s Disease Patients versus Control Subjects, and Effects of FTY720 and FTY720-Mitoxy Therapies in Parkinsonian and Multiple System Atrophy Mouse Models. J. Park. Dis. 2020, 10, 185–192.

- Belzer, C.; Chia, L.W.; Aalvink, S.; Chamlagain, B.; Piironen, V.; Knol, J.; de Vos, W.M. Microbial Metabolic Networks at the Mucus Layer Lead to Diet-Independent Butyrate and Vitamin B 12 Production by Intestinal Symbionts. Mbio 2017, 8, e00770-17.

- Barichella, M.; Severgnini, M.; Cilia, R.; Cassani, E.; Bolliri, C.; Caronni, S.; Ferri, V.; Cancello, R.; Ceccarani, C.; Faierman, S.; et al. Unraveling gut microbiota in Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 396–405.

- Hasegawa, S.; Goto, S.; Tsuji, H.; Okuno, T.; Asahara, T.; Nomoto, K.; Shibata, A.; Fujisawa, Y.; Minato, T.; Okamoto, A.; et al. Intestinal Dysbiosis and Lowered Serum Lipopolysaccharide-Binding Protein in Parkinson’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142164.

- Lin, A.; Zheng, W.; He, Y.; Tang, W.; Wei, X.; He, R.; Huang, W.; Su, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, H.; et al. Gut microbiota in patients with Parkinson’s disease in southern China. Park. Relat. Disord. 2018, 53, 82–88.

- Lin, C.-H.; Chen, C.-C.; Chiang, H.-L.; Liou, J.-M.; Chang, C.-M.; Lu, T.-P.; Chuang, E.Y.; Tai, Y.-C.; Cheng, C.; Lin, H.-Y.; et al. Altered gut microbiota and inflammatory cytokine responses in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 129.

- Mekky, J.; Ahmad, S.; Metwali, M.; Farouk, S.; Monir, S.; ElSayed, A.; Asser, S. Clinical phenotypes and constipation severity in Parkinson’s disease: Relation to Prevotella species. Microbes Infect. Dis. 2022, 3, 420–427.

- Ren, T.; Gao, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Nie, K. Gut Microbiota Altered in Mild Cognitive Impairment Compared with Normal Cognition in Sporadic Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 137.

- Baldini, F.; Hertel, J.; Sandt, E.; Thinnes, C.C.; Neuberger-Castillo, L.; Pavelka, L.; Betsou, F.; Krüger, R.; Thiele, I.; Aguayo, G.; et al. Parkinson’s disease-associated alterations of the gut microbiome predict disease-relevant changes in metabolic functions. BMC Biol. 2020, 18, 62.

More