Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes a new disease (COVID-19). Certain underlying comorbidities (e.g. asthma, cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity) have been identified as risk factors for severe COVID-19. Exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) can promote these cardio-metabolic diseases, endocrine-related cancers, and immune system dysregulation and so may also be linked to higher risk of severe COVID-19. Bisphenol A (BPA) is one of the most common EDCs, exerting its effects via receptors which are widely distributed in human tissues, including nuclear estrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), membrane-bound estrogen receptor GPR30 and human nuclear receptor estrogen-related receptor gamma. The potential role of BPA on the risk and severity of COVID-19 requires further investigation and focus should be placed on the potential role of BPA in promoting comorbidities associated with severe COVID-19, as well as on potential BPA-induced effects on key SARS-CoV-2 infection mediators, such as angiotensin‑converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), and transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2).

- SARS-CoV-2

- COVID-19

- BPA

- estrogen receptors

- ACE2

- TMPRSS2

- EDC

- endocrine disrupting chemicals

1. Introduction

Infection by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) causes a severe new disease, i.e., COVID-19. Following the initial outbreak of COVID-19 cases at the end of 2019, COVID-19 reached pandemic status within months [1]. Certain underlying diseases/conditions exhibit a direct association with significantly increased risk for adverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 [1]. Indeed, chronic respiratory diseases (e.g., asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension, diabetes, immunosuppression, and cancer are among the identified comorbidities which predispose individuals to severe COVID-19 [1].

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are exogenous substances which can disrupt normal functions of the endocrine system in animals and humans, increasing the risk of adverse health effects [2]. Common EDCs include industrial solvents or lubricants and their by-products, pesticides, fungicides, plasticisers (e.g., bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates), and pharmaceuticals [3]. EDCs are widespread in the environment and can accumulate across the entire food chain due to the long half-lives which commonly characterize these lipophilic chemicals, as well as the inability of the body to metabolize them [4]. Data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest that humans can be exposed to hundreds of chemicals including EDCs [3]. Of note, research has suggested that increased and/or prolonged exposure of humans to EDCs can cause cardio-metabolic dysfunction, disorders of the reproductive system, endocrine-related cancers, and immune system dysregulation [5].

As more data on COVID-19 become available, the identified number of relevant predisposing risk factors is increasing, including factors such as obesity [6] and low socioeconomic and/or Black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) background [7], which may be also linked to higher exposure to EDCs [8][9]. Indeed, a recent review has further proposed that long-term exposure to chemicals in mixtures, as well as lifestyle habits, may be linked to compromised immunity and predispose to the complications observed in patients with severe COVID-19 [10]. Moreover, a computational systems biology approach revealed that a number of signalling pathways which are dysregulated by EDCs (e.g., Th17 and advanced glycation end-products (AGE)/receptor for AGE (RAGE), AGE/RAGE, pathways) might also be related to the severity of COVID-19 [11]. As these detrimental effects of EDCs overlap with key risk factors for severe COVID-19, the hypothesis that exposure to EDCs may be also linked to the severity of COVID-19 merits further investigation [12].

Among the various EDCs, BPA is extensively used in a variety of products, including plastics, thermal receipts, and the lining of aluminium cans [13]. Accordingly, BPA is now one of the most frequently detected pollutants in the environment [14].

2. BPA and Key Molecular Targets of SARS-CoV-2

SARS-CoV-2 infection of target/host cells is mediated by a number of cellular receptors and proteases. As such, SARS-CoV-2 binds with high affinity to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the cell membrane, which facilitates viral entry into host cells [15]. Moreover, transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) is co-expressed with ACE2 on the cell membrane and it can prime the viral spike proteins, thus mediating the fusion of the virus with the membrane lipid layer and its uptake into host cells [16]. In addition, furin is a protease known for cleaving inactive precursor proteins into their biologically active products [17], while furin inhibitors have been investigated in the search for novel SARS-CoV-2 treatments since a relevant site has been discovered in the protein sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein [18][19].

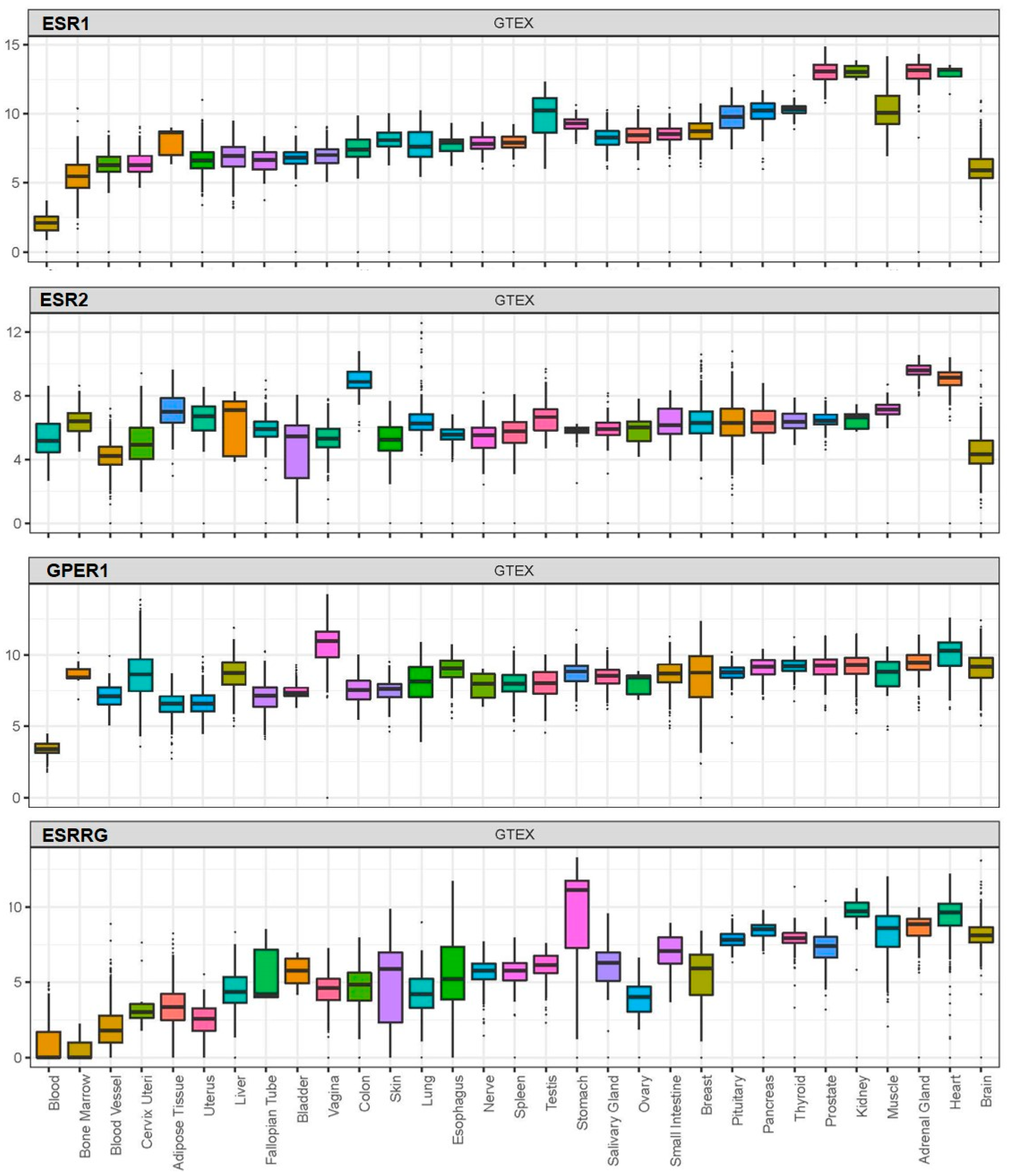

BPA exerts its effects by acting on receptors which, based on available data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project, are widely distributed in human tissues, including nuclear oestrogen receptors (ERα and ERβ), membrane-bound oestrogen receptor (G protein-coupled receptor 30; GPR30), and human nuclear receptor oestrogen-related receptor gamma (Figure 1) [20][21][22][23].

As more research is now focused on the role of cellular mediators in SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential factors affecting their expression/functions, we also present data on the potential effects of BPA on these key SARS-CoV-2 infection mediators.

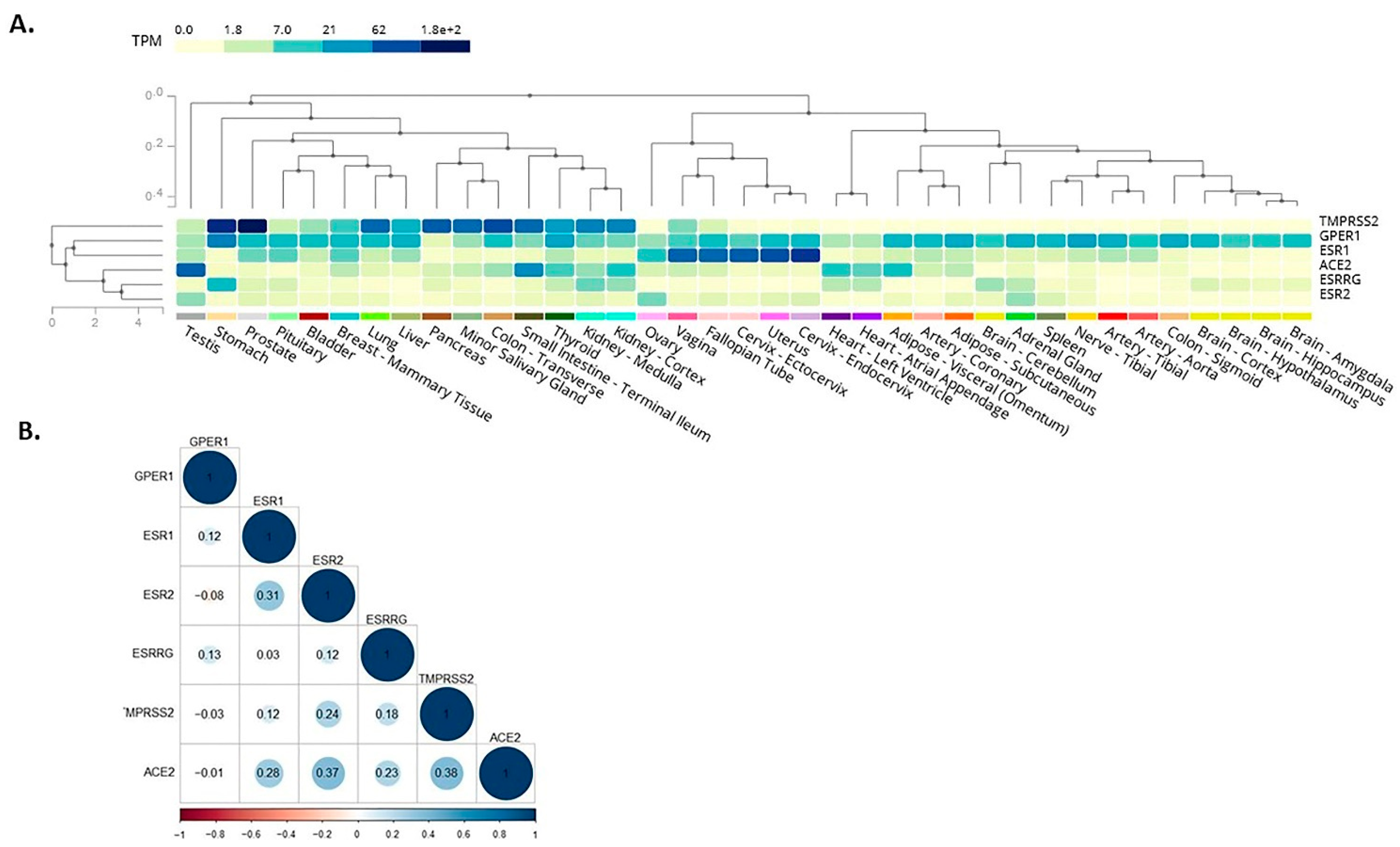

Here, we expanded on these in silico observations by assessing the co-expression of receptors mediating BPA effects with SARS-CoV-2 infection mediators. As such, among these receptors which mediate BPA effects, the membrane-bound oestrogen receptor GPR30 appeared to co-localise with TMPRSS2 in the lung, colon, stomach, small intestine, thyroid, kidney, liver, and prostate (Figure 2A). This finding suggests that BPA exposure may impact via GPR30 on these SARS-CoV-2 infection mediators in these tissues and, thus, have potential implications on the severity of COVID-19 (e.g., on the consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the lungs). We have dissected these data further, using available data from the GTEx project, to investigate any potential correlation among the expression patterns of these genes. For this, we computed the Pearson correlation coefficient between the genes’ expression levels in healthy tissue samples. A high degree of correlation was noted between ACE2 with ERβ (0.37) and TMPRSS2 (0.38), whereas moderate correlation was noted between ACE2 with ERα (0.28) and oestrogen-related receptor gamma (0.23) (Figure 2B). The results suggest that these genes have a correlated expression pattern.

3. BPA and Comorbidities Predisposing to Severe COVID-19

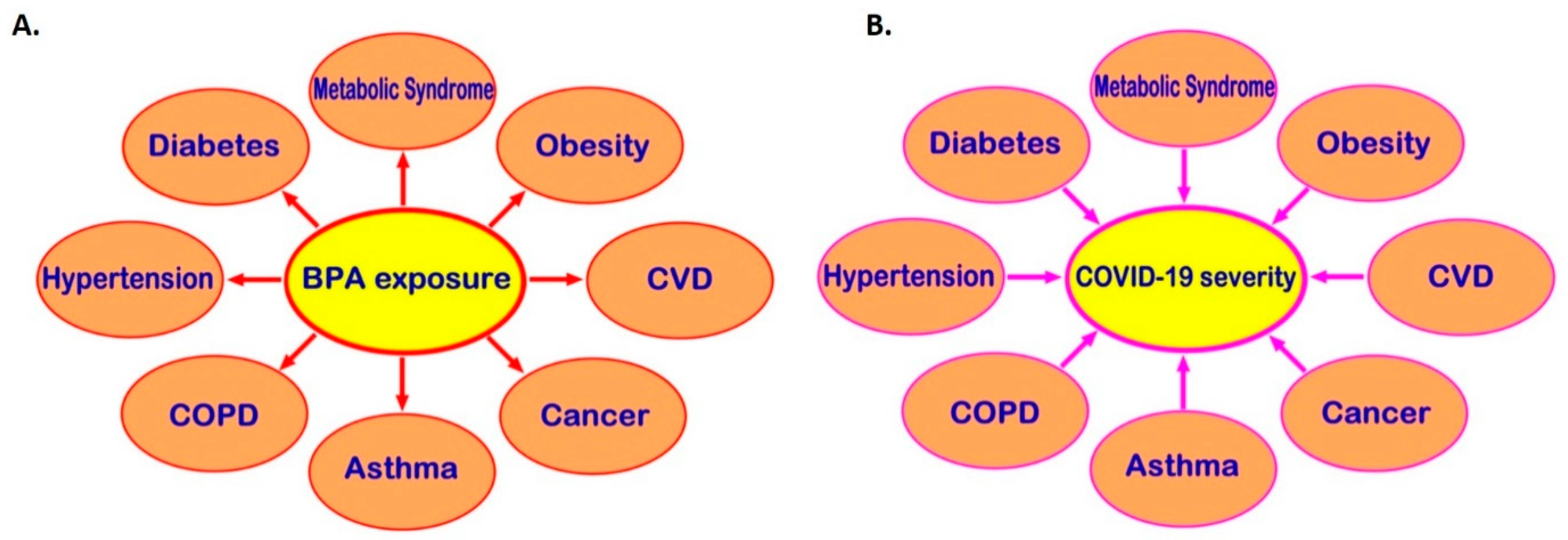

BPA exposure has been linked to the development of certain cardio-metabolic diseases, endocrine-related cancers, as well as to immune system dysregulation. The links between BPA exposure and these diseases which have been identified as risk factors for COVID-19 may be indirectly linked to higher risk of severe COVID-19.

3.1. BPA and Cardio-Metabolic Diseases

BPA is now recognized as a potential additional factor implicated in the development of cardio-metabolic diseases [24]. Indeed, BPA accumulates in adipose tissue and increases the number and size of adipocytes, thus contributing to increased adiposity and weight gain [25]. Moreover, a recent systematic review with meta-analysis of the relevant epidemiological evidence reported that BPA exposure shows a significant positive association with indices of both generalized and central/abdominal obesity [26][27]. Similarly, systematic review data also support a relationship between BPA exposure and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) [28]. BPA exposure might be also associated with adiposity both in childhood and later in life [29]. Furthermore, a positive association has also been documented between low dose BPA exposure during critical developmental periods (e.g., during fetal development) and metabolic diseases, such as T2DM [30]. Data from epidemiological and mechanistic studies also suggest a link between increased BPA exposure and hypertension [31], which is a key component of the metabolic syndrome and a leading CVD risk factor globally [32][33]. Overall, it is noteworthy that CVD and all these chronic diseases which commonly cluster within the metabolic syndrome spectrum (e.g., obesity, T2DM, and hypertension) are now consistently recognized as key factors that predispose to severe COVID-19 [34][35][36][37][38][39]. Thus, BPA exposure by promoting the development of these cardio-metabolic diseases over time may be also indirectly linked to higher risk of severe COVID-19, particularly in older individuals that are a high risk group for severe COVID-19 [40].

3.2. BPA and Cancer

BPA exposure has been linked to carcinogenicity, especially of hormone-dependent tumours, such as prostate, breast, and ovarian cancer [41]. As such, prenatal BPA exposure may influence the development of prostate cancer in later life, and also increase the frequency of breast tumours through either alteration of fetal glands or by mediating estrogen-dependent growth of tumour cells [16]. Interestingly, pregnant mice which were exposed to BPA levels within the range of human exposure showed increased prostate volume and decreased sperm production in the adult male offspring[42][43][44]. Furthermore, increasing evidence from both in vitro and animal studies suggest that BPA exposure, even at low doses, may have carcinogenic effects on breast cancer [48][45]. Moreover, BPA appears to increase the risk of endometriosis which, in turn, increases the risk of both coronary heart disease and ovarian cancer [46][47]. Finally, BPA exposure may induce endometrial stromal cell invasion and has a positive association with peritoneal endometriosis [48].

3.3. BPA and Modulation of Immune System Responses

An increasing number of studies have also drawn attention to the potential involvement of BPA in modulating immune system responses, and, particularly, to its potential ability to facilitate airway inflammation and respiratory allergies, as well as impair immunotolerance to dietary proteins [49][50][51][52]. Multiple mechanisms have been suggested to mediate the potential effects of BPA on the immune system, such as direct effects on relevant receptors (e.g., estrogen receptors) and cellular signalling pathways, as well as epigenetic effects and changes of the gut microbiome [49]. Overall, BPA exposure may impact on both the sub-type and function of the adaptive and innate immune system cells, leading to changes in produced cytokines and chemokines (e.g., upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10 and IL-4) and decreased T regulatory (Treg) cells [49][50]. Interestingly, oral BPA exposure of ovariectomized rats has been shown to induce a pro-inflammatory response in their adult female offspring, suggesting potential long-term effects of BPA on the immune system of the progeny [53].

3.4. BPA and Links to Pregnancy and Placentation Complications

A growing body of evidence has further shown that BPA exposure, even at low doses, may have adverse effects on the outcomes of pregnancy in humans, resulting in potentially harmful conditions for both the mother and the offspring (e.g., affecting the normal development of the fetus and/or causing problems later in life) [54][55][56][57][58][59][60]. There is also a correlation between BPA exposure and preeclampsia during pregnancy [61][62], which is characterized by newly diagnosed hypertension and proteinuria [63] and is associated with increased risk of both maternal mortality and health problems for the offspring later in life (e.g., obesity and T2DM) .[63][64]

4. Conclusions

Exposure to BPA, one of the most common EDCs, can promote the development of cardio-metabolic diseases, endocrine-related cancers, and immune system dysregulation and, through that, may be indirectly linked to higher risk of severe COVID-19 (Figure 3). Moreover, receptors which directly mediate BPA effects, such as the membrane-bound oestrogen receptor GPR30, are widely distributed in human tissues and may co-localise with SARS-CoV-2 infection mediators (e.g., co-localisation of GPR30 with TMPRSS2 and CTSL in the lung), potentially affecting their local tissue expression. Therefore, it becomes evident that there might be potential implications of exposure to BPA and other common EDCs on the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the severity of COVID-19 [11][12]. This is a developing topic and clearly further in vitro, computational, preclinical, and in vivo studies are needed to elucidate any such direct links between BPA and COVID-19 and clarify the molecular mechanisms that may be involved. Ultimately, this can lead to a new framework and guidelines for reducing relevant EDC exposure(s) in the context of COVID-19, particularly in high COVID-19 risk groups (e.g., men and older individuals, as well as patients with comorbidities such as T2DM, hypertension, obesity, and CVD).

References

- Richardson, S.; Hirsch, J.S.; Narasimhan, M.; Crawford, J.M.; McGinn, T.; Davidson, K.W.; Barnaby, D.P.; Becker, L.B.; Chelico, J.D.; Cohen, S.L.; et al. Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA 2020, 323, 2052.

- La Merrill, M.A.; Vandenberg, L.N.; Smith, M.T.; Goodson, W.H.; Browne, P.; Patisaul, H.B.; Guyton, K.Z.; Kortenkamp, A.; Cogliano, V.J.; Woodruff, T.J.; et al. Consensus on the key characteristics of endocrine-disrupting chemicals as a basis for hazard identification. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 45–57.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Bourguignon, J.-P.; Giudice, L.C.; Hauser, R.; Prins, G.S.; Soto, A.M.; Zoeller, R.T.; Gore, A.C. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr. Rev. 2009, 30, 293–342.

- Montes-Grajales, D.; Fennix-Agudelo, M.; Miranda-Castro, W. Occurrence of personal care products as emerging chemicals of concern in water resources: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 595, 601–614.

- Heindel, J.J.; Vandenberg, L.N. Developmental origins of health and disease. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2015, 27, 248–253.

- Stefan, N.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Schulze, M.B.; Ludwig, D.S. Obesity and impaired metabolic health in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 341–342.

- Raisi-Estabragh, Z.; McCracken, C.; Bethell, M.S.; Cooper, J.; Cooper, C.; Caulfield, M.J.; Munroe, P.B.; Harvey, N.; Petersen, S.E. Greater risk of severe COVID-19 in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic populations is not explained by cardiometabolic, socioeconomic or behavioural factors, or by 25(OH)-vitamin D status: Study of 1326 cases from the UK Biobank. J. Public Health 2020, 42, 451–460.

- Ribeiro, C.M.; Beserra, B.T.S.; Silva, N.G.; Lima, C.L.; Rocha, P.R.S.; Coelho, M.S.; Neves, F.D.A.R.; Amato, A.A. Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and anthropometric measures of obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033509.

- James-Todd, T.M.; Chiu, Y.-H.; Zota, A.R. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Environmental Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals and Women’s Reproductive Health Outcomes: Epidemiological Examples Across the Life Course. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2016, 3, 161–180.

- Tsatsakis, A.M.; Petrakis, D.; Nikolouzakis, T.K.; Docea, A.O.; Calina, D.; Vinceti, M.; Goumenou, M.; Kostoff, R.N.; Mamoulakis, C.; Aschner, M.; et al. COVID-19, an opportunity to reevaluate the correlation between long-term effects of anthropogenic pollutants on viral epidemic/pandemic events and prevalence. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 141, 111418.

- Wu, Q.; Coumoul, X.; Grandjean, P.; Barouki, R.; Audouze, K. Endocrine disrupting chemicals and COVID-19 relationships: A computational systems biology approach. MedRxiv 2020.

- Ouleghzal, H.; Rafai, M.; Elbenaye, J. Is there a link between endocrine disruptors and COVID-19 severe pneumonia? J. Heart Lung 2020.

- Peretz, J.; Vrooman, L.; Ricke, W.A.; Hunt, P.A.; Ehrlich, S.; Hauser, R.; Padmanabhan, V.; Taylor, H.S.; Swan, S.H.; Vandevoort, C.A.; et al. Bisphenol A and Reproductive Health: Update of Experimental and Human Evidence, 2007–2013. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 775–786.

- Muhamad, M.S.; Salim, M.R.; Lau, W.J.; Yusop, Z. A review on bisphenol A occurrences, health effects and treatment process via membrane technology for drinking water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 11549–11567.

- Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.-J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A.T.; Veesler, D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.

- Katopodis, P.; Anikin, V.; Randeva, H.S.; Spandidos, D.A.; Chatha, K.; Kyrou, I.; Karteris, E. Pan-cancer analysis of transmembrane protease serine 2 and cathepsin L that mediate cellular SARS-CoV-2 infection leading to COVID-19. Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 57, 533–539.

- Thomas, G. Furin at the cutting edge: From protein traffic to embryogenesis and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 753–766. =

- Coutard, B.; Valle, C.; De Lamballerie, X.; Canard, B.; Seidah, N.; Decroly, E. The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade. Antivir. Res. 2020, 176.

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Pöhlmann, S. A Multibasic Cleavage Site in the Spike Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Is Essential for Infection of Human Lung Cells. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 779–784.

- Greca, S.-C.D.A.; Kyrou, I.; Pink, R.; Randeva, H.S.; Grammatopoulos, D.; Silva, E.; Karteris, E. Involvement of the Endocrine-Disrupting Chemical Bisphenol A (BPA) in Human Placentation. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 405.

- Delfosse, V.; Grimaldi, M.; Pons, J.-L.; Boulahtouf, A.; Le Maire, A.; Cavailles, V.; Labesse, G.; Bourguet, W.; Balaguer, P. Structural and mechanistic insights into bisphenols action provide guidelines for risk assessment and discovery of bisphenol A substitutes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 14930–14935.

- Matsushima, A.; Kakuta, Y.; Teramoto, T.; Koshiba, T.; Liu, X.; Okada, H.; Tokunaga, T.; Kawabata, S.-I.; Kimura, M.; Shimohigashi, Y. Structural Evidence for Endocrine Disruptor Bisphenol A Binding to Human Nuclear Receptor ERR. J. Biochem. 2007, 142, 517–524.

- Liu, X.; Matsushima, A.; Nakamura, M.; Costa, T.; Nose, T.; Shimohigashi, Y. Fine spatial assembly for construction of the phenol-binding pocket to capture bisphenol A in the human nuclear receptor estrogen-related receptor. J. Biochem. 2012, 151, 403–415.

- Bertoli, S.; Leone, A.; Battezzati, A. Human Bisphenol A Exposure and the “Diabesity Phenotype”. Dose-Response 2015, 13.

- MacLean, P.S.; Higgins, J.A.; Giles, E.D.; Sherk, V.D.; Jackman, M.R. The role for adipose tissue in weight regain after weight loss. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 45–54.

- Wu, W.; Li, M.; Liu, A.; Wu, C.; Li, D.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, B.; Du, J.; Gao, X.; Hong, Y. Bisphenol A and the Risk of Obesity a Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis of the Epidemiological Evidence. Dose-Response 2020, 18.

- Rancière, F.; Lyons, J.G.; Loh, V.H.; Botton, J.; Galloway, T.S.; Wang, T.; Shaw, J.E.; Magliano, D.J. Bisphenol A and the risk of cardiometabolic disorders: A systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence. Environ. Health 2015, 14, 1–23.

- Sowlat, M.H.; Lotfi, S.; Yunesian, M.; Ahmadkhaniha, R.; Rastkari, N. The association between bisphenol A exposure and type-2 diabetes: A world systematic review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 21125–21140.

- Hoepner, L.A.; Whyatt, R.M.; Widen, E.M.; Hassoun, A.; Oberfield, S.E.; Mueller, N.T.; Diaz, D.; Calafat, A.M.; Perera, F.P.; Rundle, A.G. Bisphenol A and Adiposity in an Inner-City Birth Cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1644–1650.

- Alonso-Magdalena, P.; Quesada, I.; Nadal, A. Prenatal Exposure to BPA and Offspring Outcomes. Dose-Response 2015, 13.

- Han, C.; Hong, Y.-C. Bisphenol A, Hypertension, and Cardiovascular Diseases: Epidemiological, Laboratory, and Clinical Trial Evidence. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2016, 18, 1–5.

- Olsen, M.H.; Angell, S.Y.; Asma, S.; Boutouyrie, P.; Burger, D.; Chirinos, J.A.; Damasceno, A.; Delles, C.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A.-P.; Hering, D.; et al. A call to action and a lifecourse strategy to address the global burden of raised blood pressure on current and future generations: The Lancet Commission on hypertension. Lancet 2016, 388, 2665–2712.

- Bae, S.; Hong, Y.C. Exposure to bisphenol A from drinking canned beverages increases blood pressure: Randomized crossover trial. Hypertension. 2015, 65, 313–319.

- De Siqueira, J.V.V.; Almeida, L.G.; Zica, B.O.; Brum, I.B.; Barceló, A.; Galil, A.G.D.S. Impact of obesity on hospitalizations and mortality, due to COVID-19: A systematic review. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020.

- Guan, W.-J.; Ni, Z.-Y.; Hu, Y.; Liang, W.-H.; Chun-Quan, O.; He, J.-X.; Liu, L.; Shan, H.; Lei, C.-L.; Hui, D.S.; et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1708–1720.

- Li, X.; Xu, S.; Yu, M.; Wang, K.; Tao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhou, M.; Wu, B.; Yang, Z.; et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 146, 110–118.

- Klonoff, D.C.; Umpierrez, G.E. Letter to the Editor: COVID-19 in patients with diabetes: Risk factors that increase morbidity. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2020, 108, 154224.

- Zuin, M.; Rigatelli, G.; Zuliani, G.; Rigatelli, A.; Mazza, A.; Roncon, L. Arterial hypertension and risk of death in patients with COVID-19 infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2020, 81, e84–e86.

- Zaki, N.; Alashwal, H.; Ibrahim, S. Association of hypertension, diabetes, stroke, cancer, kidney disease, and high-cholesterol with COVID-19 disease severity and fatality: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 1133–1142.

- Bonanad, C.; García-Blas, S.; Tarazona-Santabalbina, F.; Sanchis, J.; Bertomeu-González, V.; Fácila, L.; Ariza, A.; Núñez, J.; Cordero, A. The Effect of Age on Mortality in Patients With COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis With 611,583 Subjects. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 915–918.

- Shafei, A.; Ramzy, M.M.; Hegazy, A.I.; Husseny, A.K.; El-Hadary, U.G.; Taha, M.M.; Mosa, A.A. The molecular mechanisms of action of the endocrine disrupting chemical bisphenol A in the development of cancer. Gene 2018, 647, 235–243.

- Saal, F.S.V.; Timms, B.G.; Montano, M.M.; Palanza, P.; Thayer, K.A.; Nagel, S.C.; Dhar, M.D.; Ganjam, V.K.; Parmigiani, S.; Welshons, W.V. Prostate enlargement in mice due to fetal exposure to low doses of estradiol or diethylstilbestrol and opposite effects at high doses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 2056–2061.

- Cagen, S.Z.; Waechter, J.M.; Dimond, S.S.; Breslin, W.J.; Butala, J.H.; Jekat, F.W.; Joiner, R.L.; Shiotsuka, R.N.; Veenstra, G.E.; Harris, L.R. Normal reproductive organ development in CF-1 mice following prenatal exposure to bisphenol A. Toxicol. Sci. 1999, 50, 36–44.

- Witorsch, R.J. Low-dose in utero effects of xenoestrogens in mice and their relevance to humans: An analytical review of the literature. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002, 40, 905–912.

- Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, S. Low-Dose Bisphenol A Exposure: A Seemingly Instigating Carcinogenic Effect on Breast Cancer. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4.

- Ruderman, R.; Pavone, M.E. Ovarian cancer in endometriosis. Clinical and molecular aspects: An update. Minerva Ginecol. 2017, 69, 286–294.

- Peinado, F.M.; Lendínez, I.; Sotelo, R.; Iribarne-Durán, L.M.; Fernández-Parra, J.; Vela-Soria, F.; Olea, N.; Fernández, M.F.; Freire, C.; León, J.; et al. Association of Urinary Levels of Bisphenols A, F, and S with Endometriosis Risk: Preliminary Results of the EndEA Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1194.

- Wen, X.; Xiong, Y.; Jin, L.; Zhang, M.; Huang, L.; Mao, Y.; Zhou, C.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Bisphenol A Exposure Enhances Endometrial Stromal Cell Invasion and Has a Positive Association with Peritoneal Endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 27, 704–712.

- Rogers, J.A.; Metz, L.; Yong, V.W. Review: Endocrine disrupting chemicals and immune responses: A focus on bisphenol-A and its potential mechanisms. Mol. Immunol. 2013, 53, 421–430.

- Xu, J.; Huang, G.; Guo, T.L. Developmental Bisphenol A Exposure Modulates Immune-Related Diseases. Toxics 2016, 4, 23.

- Khan, D.; Ahmed, S.A. Epigenetic Regulation of Non-Lymphoid Cells by Bisphenol A, a Model Endocrine Disrupter: Potential Implications for Immunoregulation. Front. Endocrinol. 2015, 6.

- Robinson, L.; Miller, R.L. The Impact of Bisphenol A and Phthalates on Allergy, Asthma, and Immune Function: A Review of Latest Findings. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 379–387.

- Braniste, V.; Jouault, A.; Gaultier, E.; Polizzi, A.; Buisson-Brenac, C.; Leveque, M.; Martin, P.G.; Theodorou, V.; Fioramonti, J.; Houdeau, E. Impact of oral bisphenol A at reference doses on intestinal barrier function and sex differences after perinatal exposure in rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 107, 448–453.

- Pergialiotis, V.; Kotrogianni, P.; Christopoulos-Timogiannakis, E.; Koutaki, D.; Daskalakis, G.; Papantoniou, N. Bisphenol A and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2018, 31, 3320–3327.

- Filardi, T.; Panimolle, F.; Lenzi, A.; Morano, S. Bisphenol A and Phthalates in Diet: An Emerging Link with Pregnancy Complications. Nutrients 2020, 12, 525.

- Mikołajewska, K.; Stragierowicz, J.; Gromadzińska, J. Bisphenol A—Application, sources of exposure and potential risks in infants, children and pregnant women. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2015, 28, 209–241.

- Berger, R.G.; Foster, W.G.; Decatanzaro, D. Bisphenol—A exposure during the period of blastocyst implantation alters uterine morphology and perturbs measures of estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in mice. Reprod. Toxicol. 2010, 30, 393–400.

- Berger, R.G.; Hancock, T.; Decatanzaro, D. Influence of oral and subcutaneous bisphenol—A on intrauterine implantation of fertilized ova in inseminated female mice. Reprod. Toxicol. 2007, 23, 138–144.

- Berger, R.G.; Shaw, J.; Decatanzaro, D. Impact of acute bisphenol—A exposure upon intrauterine implantation of fertilized ova and urinary levels of progesterone and 17β-estradiol. Reprod. Toxicol. 2008, 26, 94–99.

- Machtinger, R.; Orvieto, R. Bisphenol A, oocyte maturation, implantation, and IVF outcome: Review of animal and human data. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2014, 29, 404–410.

- Cantonwine, D.E.; Meeker, J.D.; Ferguson, K.K.; Mukherjee, B.; Hauser, R.; McElrath, T.F. Urinary Concentrations of Bisphenol A and Phthalate Metabolites Measured during Pregnancy and Risk of Preeclampsia. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1651–1655.

- Leclerc, F.; Dubois, M.-F.; Aris, A. Maternal, placental and fetal exposure to bisphenol A in women with and without preeclampsia. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2014, 33, 341–348.

- Gathiram, P.; Moodley, J. Pre-eclampsia: Its pathogenesis and pathophysiolgy. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2016, 27, 71–78.

- O’Tierney-Ginn, P.F.; Lash, G.E. Beyond pregnancy: Modulation of trophoblast invasion and its consequences for fetal growth and long-term children’s health. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2014, 105, 37–42.

- O’Tierney-Ginn, P.F.; Lash, G.E. Beyond pregnancy: Modulation of trophoblast invasion and its consequences for fetal growth and long-term children’s health. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2014, 105, 37–42.