ThLiquis paper provides insight into the various studid crystals are generally referred to as substances that have already been carried out onblend the structure and properties of solid and liquid crystalline materials based on copper(I) complexes. Even though the study of copper(I) complexstates; they share with liquids the ability to flow but also exhibit some structural arrangement similarities with respect to theirsolids. With so many compounds synthesized, liquid crystalline property is quite few,s containing metals, also known as metallomesogens prepared with different structural components and ligands from groups such as aza macrocycles, alkyl thiolates, ethers, isocyanides, phenanthroline, Schiff bases, pyrazoles, phosphine, biquinoline, and benzoyl thiourea have, have become a major subject of study. The incorporation of metal into organic matrices enhances and induces unique magnetic, spectroscopic, and redox properties of the resulting materials. At least one liquid crystalline complex has been reported. A special section is dedicated to the discussion of the emission properties of copper(I) metallomesogen in the literature for most metals.

- copper(I)

- metallomesogens

- luminescence

- complex

- ligand

- Introduction

1. Introduction

Liquid crystals are generally referred tCo as substances that blend the structure and properties of solid and liquid states, they share with liquids, the ability to flow but also exhibit some structural arrangement similarities with the solids. This intriguing combination of both the properties of the liquid and solid states gives liquid crystals the ability to induce certain properties that have gained useful applications in the displays of devices such as wristwatches, calculators, portable computers, and flat-screen televisions as well as in sensors, smart windows, optical switches, etc.[1].

With so many compopper(I) complexes have not been stunds synthesized, liquid crystals containing metals, also known as metallomesogens, have become a major subject of study [2]. Incorporation of the metal into the organic matrix enhances and induces unique magnetic, spectroscopic, and redox properties of the resultingied to a great extent as luminescent materials [3–9]. At least one liquid-crystalline complex has been reported in the literature for most of the metals. However, issues often encountered with these complexes are those relating to the high transition temperatures usually >100 C, ain the liquid crystallind the low thermal stability associated with the metallomesogens at elevated temperatures, which are major drawbacks that hinder the study of the physical properties of these materials. Consequently, the preceding challenges make it puzzling to observe light emission (luminescence) at elevated temperatures due to the strong tendencies of the excited states to undergo de-activation through nonradiative transitions. Therefore, state, but they do possess luminescence studies on metallomesogens in many cases were performed on samples in the solid state or those dissolved in organic solvents [10].

- Copper(I) metallomesogens with sulfur-containing ligands

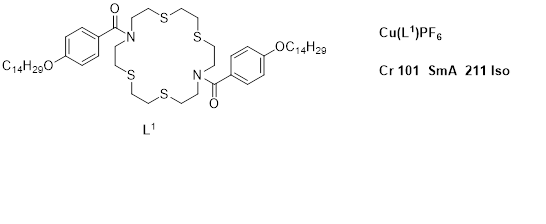

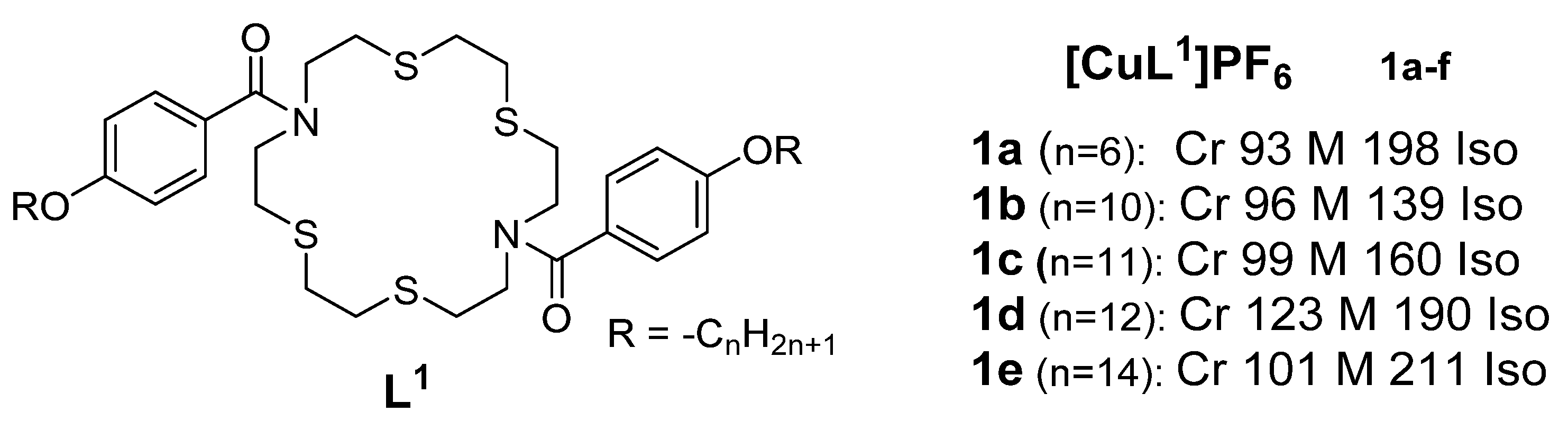

A serproperties wies of cationic macrocyclic copper(I) complexes based on non-mesogenic bis[4-(n-alkyloxy) benzamide derivatives of 1,10-diaza-4,7,13,16-tetrathiacyclooctadecane were reported in 1994 by Ghedini et al. [11]. The complexes sh great potentudied had transition temperatures from the solid to liquid crystallineals states ranging from 93-123oC[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10]. XRD measurements for Complex 1 (Figure 1) in the series and the study revealed an X-ray diffraction ppattern consistent with a disordered layered structure associated with a smectic phase of A or C type.

Figure 1: Copper(I) complexe, which is s from azamacrocycle derivative ligand. Transition temps. are in (OC) [11]

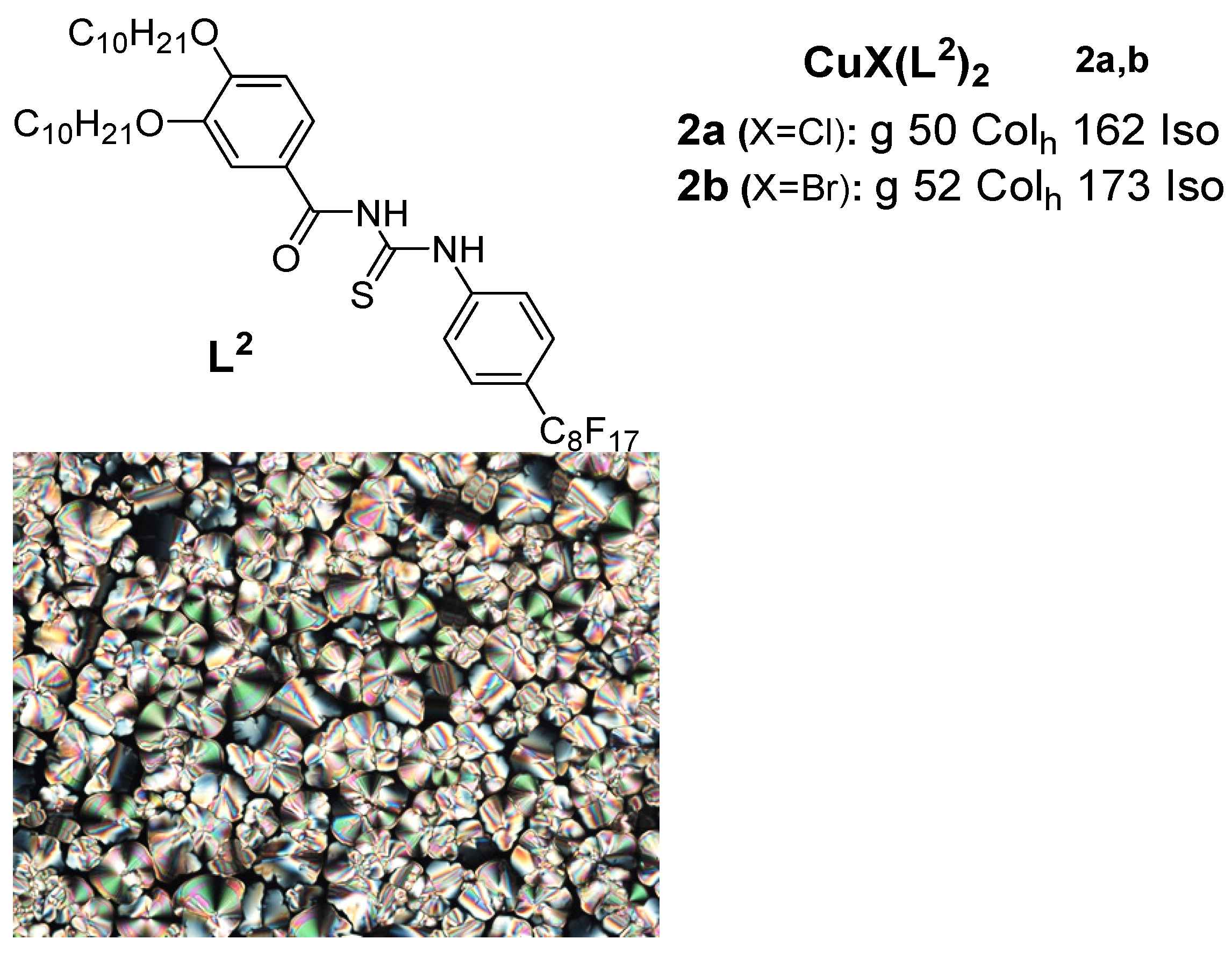

Anotewher class in the Sulphur containing ligand group is the benzoyl thiourea. An important class of copper(I) metallomesogens based on copper(I) halide complexes with thiourea-based ligands having long chain alkoxy groups and a perfluorooctyl group was reported in 2018 by Ilis and Circu [12] (Figure 2). They found no liquid crystalline property for the ligant abundant and afford but observed a hexagonal columnar phase for both complexes 2a and 2b over a high temperature above 100 C via a combination study of POMle, DSC, and XRD, while the thermal stability studied by TGA indicated a higher stability (160oC) for the corresponding copper(I) complexes compared to that of the BTU (180oC) ligand.

Figure 2: Copper(I) complexes with benzoyl thios a surea ligand. Transition temperatures are in (OC) [12].

- Copper(I) metallomesogens with N-donor ligands

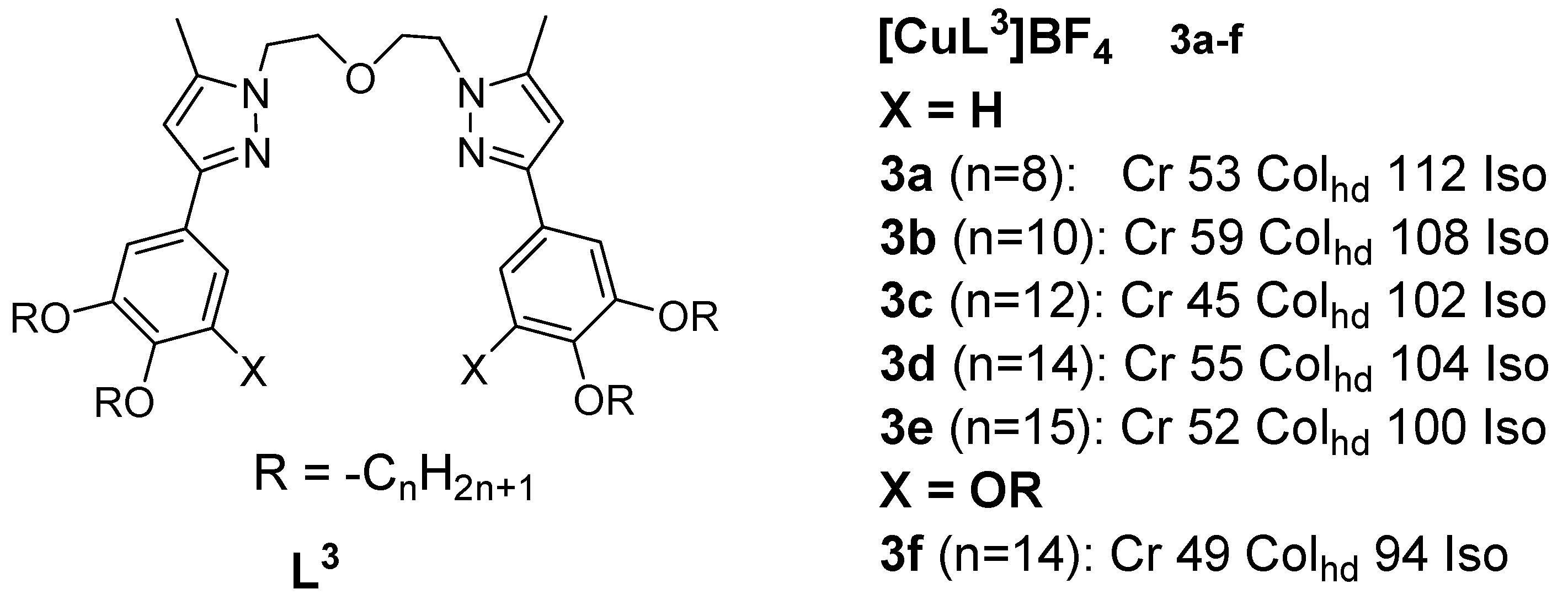

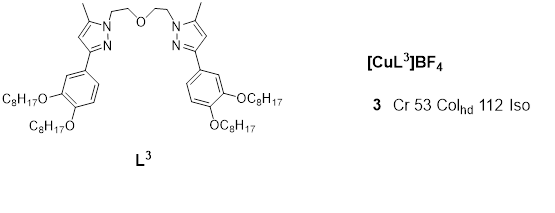

Copper(I) metallomesogens with three-coordinate geometry were first reported taby Lin et al. in 2001 [13]. The complexes were derived from bis{2-[3’-(3’’,4’’-dialkoxyphenyl)-5’-methyl-1’-pyrazolyl]ethyl} ethers and from bis{2-[3’-(3’’,4’,5’-trialkoxyphenyl)-5’-methyl-1’-pyrazolyl]ethyl} ethers. These novel complexes were obtained by complexing the ethers with [Cu(MeCN)4]BF4. An example (complex 3) is gialternativen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Copper(I) complex with ether-type ligand. All temperatures are in (oC) [13]

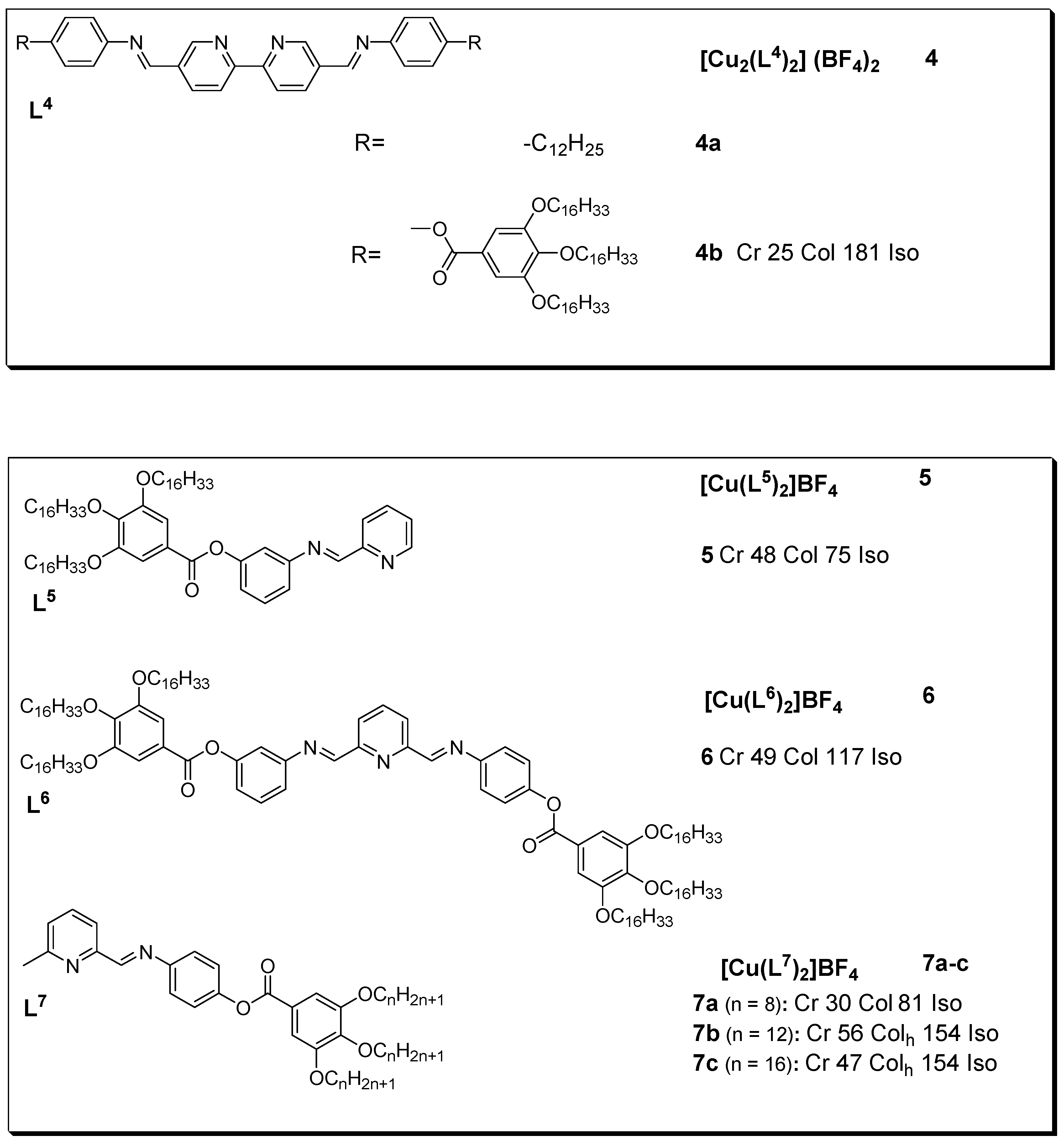

Many copper(I) complexes with N-donor ligands in the form of Schiff bases are known. These compounds show varying liquid crystalline properties with modification of their structural units. Although non mesogenic, the free ligands L4, upnoble metal con complexation with copper(I) showedes mesogenic character as described by the DSC and POM experiments[11][12]. The results indicated that complex 4 showed high stability after several heating cycles as against those for some of the other Schiff base complexes, this attribute is explained to be due to the lack of substituents at position 6 (as seen in figure 3). In addition, the optical textures observed for complex 4 during slow of triplet to singlet excooling from the isotropic melt are typical of a columnar phase (with pseudo-focal-conic textures [14].

Figure 4:tons is 3:1; Copper(I) metallomesogens with Schiff base. All transition temperatures are in (oC) [14].

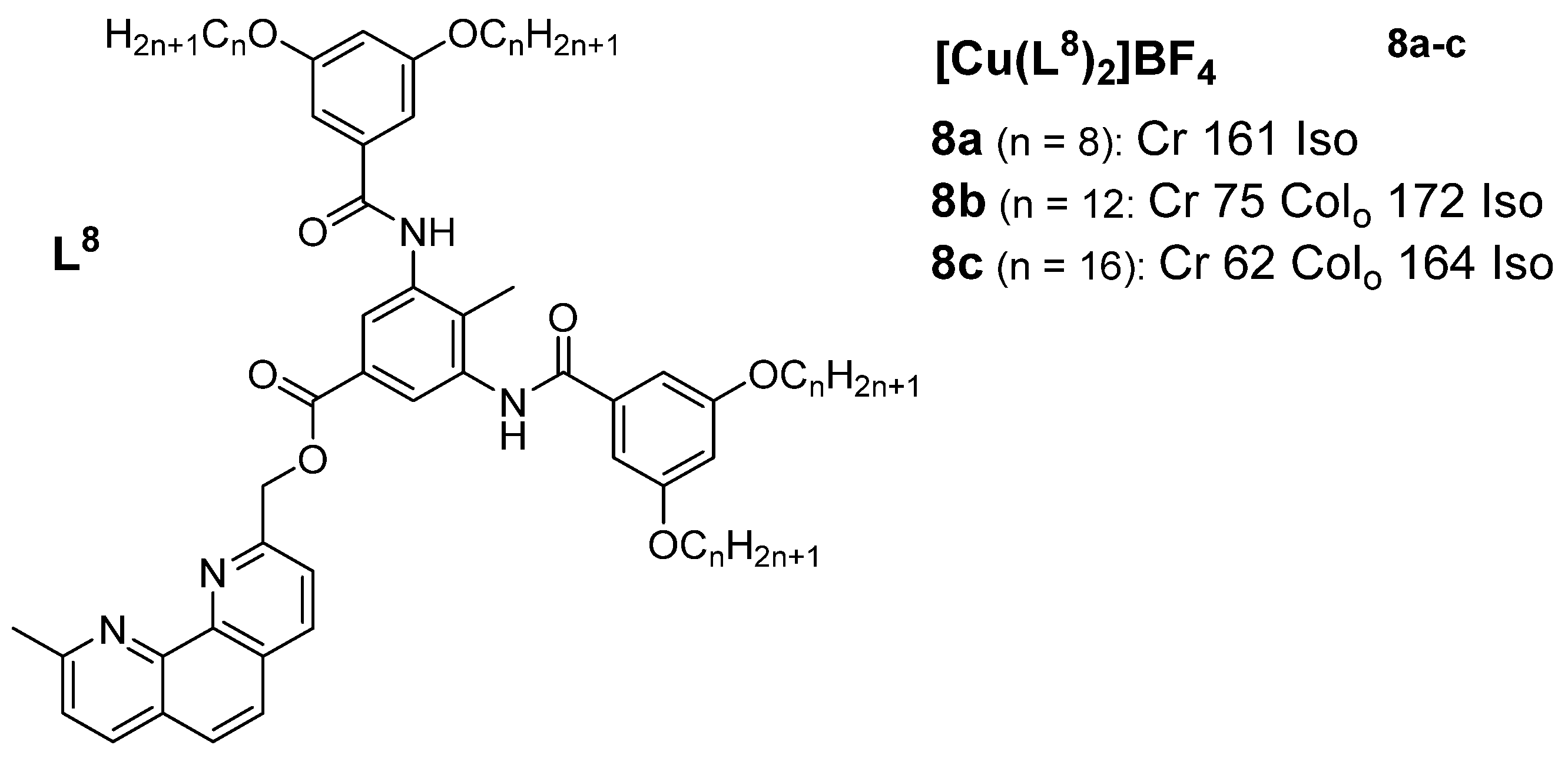

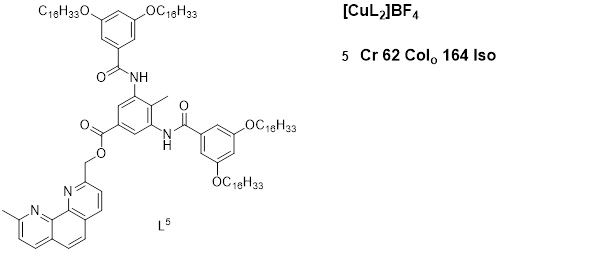

A stonsequdy by Ziessel et al. (2004) [15] presented mesomorphic materials based on copper(I) complexes with phenanthroline-based ligands. The study aimed to engineer a structural framework with additional supramolecular binding factors (hydrogen bonding) so as to stabilize the mesophase both as a free ligand and within the complex. The thermotropic properties of the ligands and complexes of the phenanthroline derivatives were investigated via a combination of POM, DSC, and XRD. The ligand used for the complexes showed distinct cubic and disordered lamellar mesophases at the related copper(I) complexes with longer chains showing mesomorphic behaviors displaying mesophases characteristic of the oblique columnar phase. An example of such compounds is described in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Copper(I) complex with pheny, for luminescent materials to be used in OLEDs, they should essentially be anthroline-based ligand. Temperatures are in (OC) [15]

- Copper(I) metallomesogens with isocyanide ligands

The reacle tion of isocyanides with CuX (X is halide) gives a mononuclear complex but, on the contrary, the reaction of two equivalents of the isocyanide derivatives with CuX yields binuclear harvest all the excitons. Because copper(I) complexes, an example of metallomesogens from the aforementioned ligand is shown in Figures 6.

Figure 6: Mononuclear and dinuclear copper(I) Isocyanide complexes. Transi exhibition temperatures are in bracket (OC) [16] [17]

The first set variof liquid crystals based on copper(I) isocyanide complexes was reported in 2001 by Benouazzane et al [16]. Some of s metal-the isocyanide ligands were reported to display nematic and/or smectic A phases. The mononuclear copper complex 6 (fi-ligand chargure 6) shows SmA and SmC mesophases.

Chico et al. [17] reported two isocyanate-tripheanylene copper(I) complexes both of which display good thermal stability in the range of study. The free isocyanide ligand appeared not to be mesomorphic as observed by POM. The identification of the columnar mesophase for the dinuclear complex 7 (figure 6) was achieved by small-a (MLCT) behaviors, they cangle X-ray scattering on powder samples which was measured as a function of temperature, consistent with the DSC and POM experiments. Furthermore, the columnar mesophase was stable in the temperature range of 46 to 79OC.

- Luminescent metallomesogens based on copper(I) complexes

A major drawback in the stinduce spin orbital coudy of the physical properties of metallomesogens is mostly due to issues relating to their high transition temperatureling of the triplet and stability at those elevated temperatures. It becomes increasingly difficult to study the emissions at those temperatures due to the strong tendencies of the excited electrons to undergo deactivation via nonradiative transitions [10]. Few attempts have been made in this regard and interesting findings have been made.

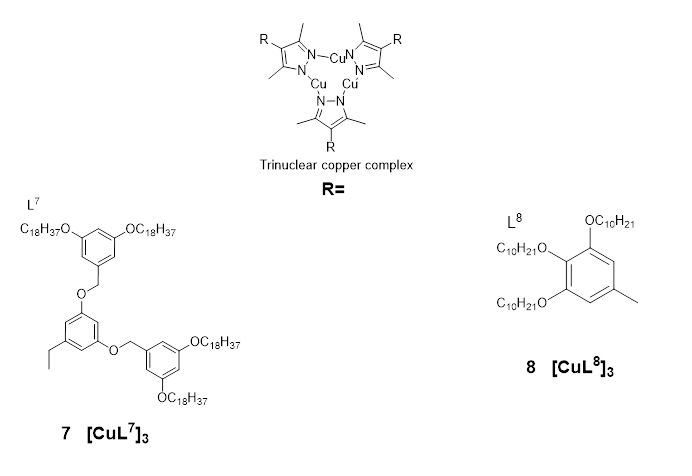

Kishimura et al. were the first tinglet states, leading to describe the emission properties of copper(I) complexes in their liquid crystalline phase [18] in 2005. They reported a number of dendritic Cu(I) pyrazolate complexes which were used to produce some thermally rewritable phosphorescent papers useful for security purposes.

Figure 7: Ligamall energy separationds and representative structure of the copper pyrazole trinuclear complex 7 & 8 reported in [18] [19]

The luminescence investibetween the energation of complexes from the pyrazole ligand [18] revealed dichroism levels at room temperature for the solid of complex 7[13]. Cooling of tThe hot melt (which emitted a red luminescence at λmax650 nm) naturais ally or by slow cooling leads to blue shift emission at 640 or 610 nm respectively. In essence, the red and yellow luminescence observed for 7 could be thermally changed from one form to the other, dependws for reverse ing on the manner and rate of cooling and this was also found to be the case for its liquid crystalline properties. Both the aged and non-aged complex 7 that was analyzed appeatersystem cred to be phosphorescent which is thought to be a result of Cu(I) to Cu(I) interactions [18]ssing (RISC), i.e.

Furthermore, XRD analysis of the aged sample of complex 7 showed diffracngletion patterns synonymous with a one-dimensional columnar phase and the same, 7 harviewed in a polarized optical microscope showed a fan-shaped texture that is characteristic of Discotic liquid crystals and on the basis of this, was concluded that aged complex 7 is composed of long-sting, range discotic columnar assembly. XRD pattern of the non-aged complex after natural cooling also indicated the presence of a columnar structure. DSC measurements carried out on the aged and non-aged complex 7 reveasulting in thermalledy patterns, upon which it was concluded that the discotic columnar assembly which is believed to involve metallophilic interactions of the Cu(I) to Cu(I) units having long alkyl chains, is formed in the aging process at about 40–50 °C. The stability of the dichroic luminescence was therefore found to be dependent on the pyrazole ligand structure.

Buildiactivated delayed fluoresceng upon the aforementioned work by Kishimura and co-workers, Gimenez et al. e (2020TADF) [19][14]. rThecently reported a series ofrefore, liquid crystals achieved with cyclic trinuclearbased on copper(I) complexes (the most important in the series is given in Figure 7 as complex 8), prepared uhave consing 3,5-dimethyl-4-(trialkoxyphenyl)pyrazolate ligands.

Complerable promisex 8 wasfor reported to have orange-red colored emissions at room temperature and the photoroducing effective luminescence exhibited a broad band centered at around 661-664 nm. A landmark reported in this study [19] is the high Quantum yield (QY) value of 42%, measured in the liquid crystalline state which is the highest recorded so far for any copper(I) metallomesogens. The QY obtained for complex 7 in its liquid crystalline state t materials for a was higher than those obtained in the crystalline state of complexes for the rest of the series. Thus, the work carried out by Giminez et al.[19] have shown that de range of opticalow-temperature phosphorescent metallomesogens can be obtained from the more affordable and abundant copper metal.

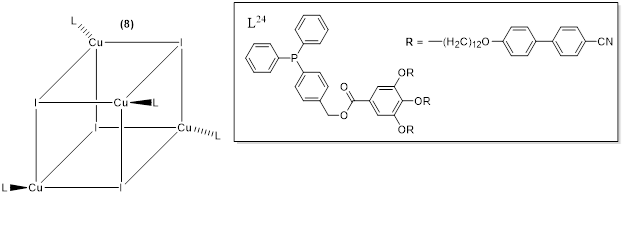

Camerel et al. (2016) [20] reported a new class of copper(I) lor electro-optiquid crystals with a cubane core and based on phosphine ligands functionalized with pro mesogenic gallate-based moieties bearing either long alkyl chains of C8, C12, and C16 or cyanobiphenyl (CBP) fragments. The copper(I) cubanes have already been known for being able to display both luminescence mechanochromism and thermochromism behavior [21–25]. This study is an inventive example of integrating luminescence characteristics of copper iodide clusters [Cu4I4(L24)4] wal applications due to the large diversity of possith the flexible self-assembly of liquid crystals. Only the compound functionalized with cyano biphenyl group (CBP) i.e., Complex 8 (figutructure 8) showed liquid crystalline behaviour displaying a Sm A from room temperature to about 1000C.

Figure 8. Ge, including moneral structure of the functionalized [Cu4I4(L24)4] copper iodide clusters with phosphine ligands [20].

All the complexes farom the work by Camerel et al. [20] revealed luminescence thermochromism for all the studied comor pounds however, complex 8 displayed an unclassical behavior which was attributed to the intrinsic luminescence properties of the cyano biphenyl moiety itself, complex 8 uclear complexes, andisplayed a dual-emissive system which presented interesting emission properties. And also, in addition to its liquid crystalline properties, the compound 8 dthe great potentisplayed luminescence mechanochromism with a modification of the el of emission wavelength in response to grindingbehavior.

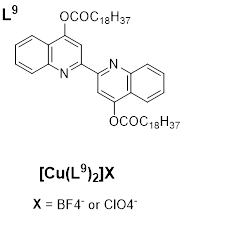

Cretu et al. (2018) [26] reported a Inew class of Cu(I) coordination complexes having 4,4’-bisubstituted-2,2’-biquinolines which shows low-temperature lamella-columnar and columnar hexagonal thermotropic liquid crystalline phases. The highest deduction from the luminescence study is the presence, at 578 and 560 nm of a medium-low intensity band, with a series of shoulders, believed to be due to metal-to-ligand charge-transfer (MLCT) electronic transitions. By heating the solid samples, they move towards the liquid-crystalline phases and still retain the luminescence displayed in the solid state but by increasing the temperature, the intensity of the luminescence band decreases, and when over 120°C, luminescence is completely quenched; but returns with subsequent cooling of the samples. This behavior is attributed to the gain of the non-radiative kinetic constants when vibrational modes are enhanced by heating the samples [26]. An example of this class’s structure is given in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Copper(Iaddition, the range of coordination geometries (such as linear, plan-trigonal, or tetrahedral) complex with bisubstituted biquinoline ligand [26]

Conclusion

The aned wim of this article was to make an overview of the various liquid crystalline materials based on copper(I) complexes with an emphasis on their luminescent properties. Examples of copper(I) metallomesogens based on isocyanide ligands are by far the most prevalent. By utilizing the suitable mesogenic groups, their LC characteristics may be simply modified. While a few other isocyanides produced hexagonal and rectangular columnar phases as well as a cubic phase for the dendritic isocyanide supermolecules, the bulk of these complexes exhibit calamitic behavior with either SmA or SmC phases. The reported copper(I) complexes of Schiff base type ligands of bipyridine imine, 2-aminopyridine, and picoline substituted imino ligand and those of alkyl thiolates all displayed varying columnar mesophases with different transition temperature ranges. Both the ether type and benzoyl thiourea ligands displayed characteristics of a hexagonal columnar mesophase for the corresponding metallomesogens, while the copper(I) complexes from phenanthroline ligands had an oblique columnar m the ligands’ structural design provide a significant benefit for controlling the LC properties, including their enhanced thermal stability and mesophase. Furthermore, interesting luminescent properties in liquid crystalline states were observed for copper(I) complexes from ligands with pyrazole derivatives, phosphine ligands functionalized with copper iodide and substituted biquinoline ligands. The complex from the functionalized phosphine ligand displayed interesting mechanochromic luminescence properties. A high quantum yield of 42% in the liquid crystalline phase of the copper(I) metallomesogens from a pyrazole ligand was reported. This work provides a pillar to build on for the preparation of many more copper(I) complexes having liquid crystalline behavior with improved properties type related to both calamitic and discotic materials.

R

2. Copper(I) Metallomesogens with Sulfur-Containing Ligands

3. Copper(I) Metallomesogens with N-Donor Ligands

- Handbook of Liquid Crystals. Handbook of Liquid Crystals 2014, doi:10.1002/9783527671403.

- Date, R.W.; Iglesias, E.F.; Rowe, K.E.; Elliott, J.M.; Bruce, D.W. Metallomesogens by Ligand Design. Dalton Transactions 2003, 10, 1914–1931, doi:10.1039/B212610A.

- Flora, S.J.S. Chelation Therapy. Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry II (Second Edition): From Elements to Applications 2013, 3, 987–1013, doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097774-4.00340-5.

- Gilli, J.M.; Thiberge, S.; Manaila-Maximean, D. New Aspect of the Voltage/Confinement Ratio Phase Diagram for a Confined Homeotropic Cholesteric. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15421400490478858 2010, 417, doi:10.1080/15421400490478858.

- Micutz, M.; Iliş, M.; Staicu, T.; Dumitraşcu, F.; Pasuk, I.; Molard, Y.; Roisnel, T.; Cîrcu, V. Luminescent Liquid Crystalline Materials Based on Palladium(II) Imine Derivatives Containing the 2-Phenylpyridine Core. Dalton Transactions 2013, 43, 1151–1161, doi:10.1039/C3DT52137K.

- Al-Karawi, A.J.M. From Mesogens to Metallomesogens. Synthesis, Characterisation, Liquid Crystal and Luminescent Properties. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678292.2017.1371799 2017, 44, 2285–2300, doi:10.1080/02678292.2017.1371799.

- Cuerva, C.; Cano, M.; Lodeiro, C. Advanced Functional Luminescent Metallomesogens: The Key Role of the Metal Center. Chem Rev 2021, 121, 12966–13010, doi:10.1021/ACS.CHEMREV.1C00011.

- Thaker, B.; Limbachiya, N.; Patel, K.; Patel, N. Calamitic Liquid Crystals Involving Fused Ring and Their Metallomesogens. Emerging Materials Research 2017, 6, 331–347, doi:10.1680/JEMMR.15.00060/ASSET/IMAGES/SMALL/JEMMR6-0331-F10.GIF.

- Zou, G.; Zhang, S.; Feng, S.; Li, Q.; Yang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, K.; Wen, T. Bin Cyclometalated Platinum(II) Metallomesogens Based on Half-Disc-Shaped β-Diketonate Ligands with Hexacatenar: Crystal Structures, Mesophase Properties, and Semiconductor Devices. Inorg Chem 2022, 61, 11702–11714, doi:10.1021/ACS.INORGCHEM.2C01327.

- Binnemans, K. Luminescence of Metallomesogens in the Liquid Crystal State. J Mater Chem 2009, 19, 448–453, doi:10.1039/B811373D.

- Neve, F.; Ghedini, M.; Levelut, A.M.; Francescangeli, O. Ionic Metallomesogens. Lamellar Mesophases in Copper(I) Azamacrocyclic Complexes. Chemistry of Materials 1994, 6, 70–76, doi:10.1021/CM00037A016/ASSET/CM00037A016.FP.PNG_V03.

- Iliş, M.; Cîrcu, V. Discotic Liquid Crystals Based on Cu(I) Complexes with Benzoylthiourea Derivatives Containing a Perfluoroalkyl Chain. J Chem 2018, 2018, doi:10.1155/2018/7943763.

- Lin, H. da; Lai, C.K. Ionic Columnar Metallomesogens Formed by Three-Coordinated Copper(I) Complexes. Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions 2001, 2383–2387, doi:10.1039/B103427H.

- Douce, L.; El-Ghayoury, A.; Skoulios, A.; Ziessel, R. Columnar Mesophases from Tetrahedral Copper( I ) Cores and Schiff-Base Derived Polycatenar Ligands. Chemical Communications 1999, 0, 2033–2034, doi:10.1039/A904245H.

- Ziessel, R.; Pickaert, G.; Camerel, F.; Donnio, B.; Guillon, D.; Cesario, M.; Prangé, T. Tuning Organogels and Mesophases Will Phenanthroline Ligands and Their Copper Complexes by Inter- to Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonds. J Am Chem Soc 2004, 126, 12403–12413, doi:10.1021/JA047091A/SUPPL_FILE/JA047091ASI20040708_044005.PDF.

- Benouazzane, M.; Coco, S.; Espinet, P.; Barberá, J. Supramolecular Organization in Copper(I) Isocyanide Complexes: Copper(I) Liquid Crystals from a Simple Molecular Structure. J Mater Chem 2001, 11, 1740–1744, doi:10.1039/B100548K.

- Chico, R.; de Domingo, E.; Domínguez, C.; Donnio, B.; Heinrich, B.; Termine, R.; Golemme, A.; Coco, S.; Espinet, P. High One-Dimensional Charge Mobility in Semiconducting Columnar Mesophases of Isocyano-Triphenylene Metal Complexes. Chemistry of Materials 2017, 29, 7587–7595, doi:10.1021/ACS.CHEMMATER.7B02922/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/CM-2017-029226_0009.JPEG.

- Kishimura, A.; Yamashita, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Aida, T. Rewritable Phosphorescent Paper by the Control of Competing Kinetic and Thermodynamic Self-Assembling Events. Nat Mater 2005, 4, 546–549, doi:10.1038/NMAT1401.

- Giménez, R.; Crespo, O.; Diosdado, B.; Elduque, A. Liquid Crystalline Copper(i) Complexes with Bright Room Temperature Phosphorescence. J Mater Chem C Mater 2020, 8, 6552–6557, doi:10.1039/d0tc00642d.

- Huitorel, B.; Benito, Q.; Fargues, A.; Garcia, A.; Gacoin, T.; Boilot, J.P.; Perruchas, S.; Camerel, F. Mechanochromic Luminescence and Liquid Crystallinity of Molecular Copper Clusters. Chemistry of Materials 2016, 28, 8190–8200, doi:10.1021/ACS.CHEMMATER.6B03002/SUPPL_FILE/CM6B03002_SI_001.PDF.

- Benito, Q.; Baptiste, B.; Polian, A.; Delbes, L.; Martinelli, L.; Gacoin, T.; Boilot, J.P.; Perruchas, S. Pressure Control of Cuprophilic Interactions in a Luminescent Mechanochromic Copper Cluster. Inorg Chem 2015, 54, 9821–9825, doi:10.1021/ACS.INORGCHEM.5B01546/SUPPL_FILE/IC5B01546_SI_002.CIF.

- Tsuge, K.; Chishina, Y.; Hashiguchi, H.; Sasaki, Y.; Kato, M.; Ishizaka, S.; Kitamura, N. Luminescent Copper(I) Complexes with Halogenido-Bridged Dimeric Core. Coord Chem Rev 2016, 306, 636–651, doi:10.1016/J.CCR.2015.03.022.

- Volz, D.; Zink, D.M.; Bocksrocker, T.; Friedrichs, J.; Nieger, M.; Baumann, T.; Lemmer, U.; Bräse, S. Molecular Construction Kit for Tuning Solubility, Stability and Luminescence Properties: Heteroleptic MePyrPHOS-Copper Iodide-Complexes and Their Application in Organic Light-Emitting Diodes. Chemistry of Materials 2013, 25, 3414–3426, doi:10.1021/CM4010807/SUPPL_FILE/CM4010807_SI_001.PDF.

- Liu, Z.; Qiu, J.; Wei, F.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Helander, M.G.; Rodney, S.; Wang, Z.; Bian, Z.; Lu, Z.; et al. Simple and High Efficiency Phosphorescence Organic Light-Emitting Diodes with Codeposited Copper(I) Emitter. Chemistry of Materials 2014, 26, 2368–2373, doi:10.1021/CM5006086/SUPPL_FILE/CM5006086_SI_001.PDF.

- Cariati, E.; Lucenti, E.; Botta, C.; Giovanella, U.; Marinotto, D.; Righetto, S. Review. Coord Chem Rev 2016, Part 2, 566–614, doi:10.1016/J.CCR.2015.03.004.

26. Cretu, C.; Andelescu, A.A.; Candreva, A.; Crispini, A.; Szerb, E.I.; la Deda, M. Bisubstituted-Biquinoline Cu(I) Complexes: Synthesis, Mesomorphism and Photophysical Studies in Solution and Condensed States. J Mater Chem C Mater 201

8, 6, 10073–10082, doi:10.1039/C8TC02999G.

References

- Tudor, C.A.; Iliş, M.; Secu, M.; Ferbinteanu, M.; Cîrcu, V. Luminescent heteroleptic copper(I) complexes with phosphine and N-benzoyl thiourea ligands: Synthesis, structure and emission properties. Polyhedron 2022, 211, 115542.

- Favarin, L.R.V.; Rosa, P.P.; Pizzuti, L.; Machulek, A.; Caires, A.R.L.; Bezerra, L.S.; Pinto, L.M.C.; Maia, G.; Gatto, C.C.; Back, D.F.; et al. Synthesis and structural characterization of new heteroleptic copper(I) complexes based on mixed phosphine/thiocarbamoyl-pyrazoline ligands. Polyhedron 2017, 121, 185–190.

- Chan, K.C.; Cheng, S.C.; Lo, L.T.L.; Yiu, S.M.; Ko, C.C. Luminescent Charge-Neutral Copper(I) Phenanthroline Complexes with Isocyanoborate Ligand. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 2018, 897–903.

- Bergmann, L.; Friedrichs, J.; Mydlak, M.; Baumann, T.; Nieger, M.; Bräse, S. Outstanding luminescence from neutral copper(i) complexes with pyridyl-tetrazolate and phosphine ligands. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 6501–6503.

- Enikeeva, K.R.; Shamsieva, A.V.; Strelnik, A.G.; Fayzullin, R.R.; Zakharychev, D.V.; Kolesnikov, I.E.; Dayanova, I.R.; Gerasimova, T.P.; Strelnik, I.D.; Musina, E.I.; et al. Green Emissive Copper(I) Coordination Polymer Supported by the Diethylpyridylphosphine Ligand as a Luminescent Sensor for Overheating Processes. Molecules 2023, 28, 706.

- Tsuge, K.; Chishina, Y.; Hashiguchi, H.; Sasaki, Y.; Kato, M.; Ishizaka, S.; Kitamura, N. Luminescent copper(I) complexes with halogenido-bridged dimeric core. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 306, 636–651.

- Sun, Y.; Lemaur, V.; Beltrán, J.I.; Cornil, J.; Huang, J.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Fröhlich, R.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L.; et al. Neutral Mononuclear Copper(I) Complexes: Synthesis, Crystal Structures, and Photophysical Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 5845–5852.

- Borges, A.P.; Carneiro, Z.A.; Prado, F.S.; Souza, J.R.; Silva, L.H.F.E.; Oliveira, C.G.; Deflon, V.M.; de Albuquerque, S.; Leite, N.B.; Machado, A.E.H.; et al. Cu(I) complexes with thiosemicarbazides derived from p-toluenesulfohydrazide: Structural, luminescence and biological studies. Polyhedron 2018, 155, 170–179.

- Brown, C.M.; Li, C.; Carta, V.; Li, W.; Xu, Z.; Stroppa, P.H.F.; Samuel, I.D.W.; Zysman-Colman, E.; Wolf, M.O. Influence of Sulfur Oxidation State and Substituents on Sulfur-Bridged Luminescent Copper(I) Complexes Showing Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 7156–7168.

- Bergmann, L.; Braun, C.; Nieger, M.; Bräse, S. The coordination- and photochemistry of copper(i) complexes: Variation of N^N ligands from imidazole to tetrazole. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 608–621.

- Li, X.; Xie, Y.; Li, Z. Diversity of Luminescent Metal Complexes in OLEDs: Beyond Traditional Precious Metals. Chem. Asian J. 2021, 16, 2817–2829.

- Dumur, F. Recent advances in organic light-emitting devices comprising copper complexes: A realistic approach for low-cost and highly emissive devices? Org. Electron. 2015, 21, 27–39.

- Yersin, H.; Czerwieniec, R.; Shafikov, M.Z.; Suleymanova, A.F. TADF Material Design: Photophysical Background and Case Studies Focusing on Cu(I) and Ag(I) Complexes in Highly Efficient OLEDs: Materials Based on Thermally Activated Delayed Fluorescence; Yersin, H., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1–60.

- Housecroft, C.E.; Constable, E.C. TADF: Enabling luminescent copper(i) coordination compounds for light-emitting electrochemical cells. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 4456–4482.

- Neve, F.; Ghedini, M.; Levelut, A.-M.; Francescangeli, O. Ionic metallomesogens. Lamellar mesophases in copper(I) azamacrocyclic complexes. Chem. Mater. 1994, 6, 70–76.

- Espinet, P.; Carmen Lequerica, M.; Martín-Alvarez, J.M.Â. Synthesis, Structural Characterization and Mesogenic Behavior of Copper(I) n-Alkylthiolates. Chem. Eur. J. 1999, 5, 1982–1986.

- Dance, I.G.; Fisher, K.J.; Banda, R.M.H.; Scudder, M.L. Layered Structure of Crystalline Compounds AgSR. Inorg. Chem. 1991, 30, 183–187.

- Iliş, M.; Cîrcu, V. Discotic Liquid Crystals Based on Cu(I) Complexes with Benzoylthiourea Derivatives Containing a Perfluoroalkyl Chain. J. Chem. 2018, 2018, 7943763.

- Lin, H.-D.; Lai, C.K. Ionic columnar metallomesogens formed by three-coordinated copper(I) complexes. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2001, 2383–2387.

- Raczuk, E.; Dmochowska, B.; Samaszko-Fiertek, J.; Madaj, J. Different Schiff Bases—Structure, Importance and Classification. Molecules 2022, 27, 787.

- Khalaji, A.D. Structural Diversity on Copper(I) Schiff Base Complexes, Current Trends in X-Ray Crystallography. Chandrasekaran, Q., Ed.; InTech: London, UK, 2011; pp. 161–190. ISBN 978-953-307-754-3.

- Jamain, Z.; Azman, A.N.A.; Razali, N.A.; Makmud, M.Z.H. A Review on Mesophase and Physical Properties of Cyclotriphosphazene Derivatives with Schiff Base Linkage. Crystals 2022, 12, 1174.

- Rananavarem, S.B.; Pisipati, V.G.K.M. An Overview of Liquid Crystals Based on Schiff Base Compounds, Liquid Crystalline Organic Compounds and Polymers as Materials XXI Century: From Synthesis to Applications; Iwan, A., Schab-Balcerzak, E., Eds.; Transworld Research Network: Trivandrum, Kerala, 2011; ISBN 978-81-7895-496-7.

- Hoshino, N. Liquid crystal properties of metal–salicylaldimine complexes.: Chemical modifications towards lower symmetry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1998, 174, 77–108.

- Torroba, J.; Bruce, D.W. Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry II: From Elements to Applications, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 8, pp. 837–917.

- El-Ghayoury, A.; Douce, L.; Skoulios, A.; Ziessel, R. Cation-Induced Macroscopic Ordering of Non-Mesomorphic Modules—A New Application for Metallohelicates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 2205–2208.

- Douce, L.; Diep, T.H.; Ziessel, R.; Skoulios, A.; Césario, M. Columnar liquid crystals from wedge-shaped tetrahedral copper(i) complexes. J. Mater. Chem. 2003, 13, 1533–1539.

- Douce, L.; El-Ghayoury, A.; Ziessel, R.; Skoulios, A. Columnar mesophases from tetrahedral copper(I) cores and Schiff-base derived polycatenar ligands. Chem. Commun. 1999, 2033–2034.

- Ziessel, R.; Pickaert, G.; Camerel, F.; Donnio, B.; Guillon, D.; Cesario, M.; Prangé, T. Tuning Organogels and Mesophases Will Phenanthroline Ligands and Their Copper Complexes by Inter- to Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 12403–12413.