Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Alessandra Larocca and Version 2 by Sirius Huang.

While novel therapies have improved outcomes in multiple myeloma (MM), physicians are calling for greater caution when managing this hematologic malignancy in older patients due to their fragility, which increases their vulnerability to toxic events. Additionally, this patient population may be excluded from clinical trials due to comorbidities, whereby available data are not always applicable in real-word clinical practice.

- multiple myeloma

- elderly patients

- frailty

1. Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematologic malignancy that typically occurs in older patients. The median age at the time of diagnosis is 69 years, and more than 30% of patients are older than 75 years [1].

Although new therapies have improved median survival, reaching approximately 6 years [2], the available data suggest that age is a major parameter affecting outcome, which worsens decade by decade, reaching about 28.9 months of median overall survival (OS) in patients aged 80 years and older [3]. The impact of age on survival is also highlighted in many major clinical trials, although the selection of patients enrolled in these studies does not totally reflect the characteristics of the real-world population [3][4][5][3,4,5].

In addition to chronological age, other factors such as the incidence and severity of comorbidities, functional impairments, and independence status are strong predictors of life expectancy [6], which is extremely variable in the same age group, thus suggesting that not only chronological age is important, but also health status.

Although the trend in MM research has always been to increase the efficacy of the therapy by combining different drugs (doublets, triplets, and quadruplets), this does not always translate into a benefit, particularly in more frail patients, who are more sensitive to possible adverse toxicities [7].

Furthermore, the efficacy of therapies tends to decrease during the course of the disease, while the proportion of patients receiving therapies at each subsequent line also constantly decreases. In a study published by Yong and colleagues, including 22% of patients over 75 years old, 62% of patients received second-line treatment, and <25% actually received three lines of therapy [8]. This concept was also highlighted by Fonseca e al. in their study, which showed that transplant-ineligible (NTE) patients who received just one line of therapy were significantly older and exhibited a higher incidence of comorbidities [9].

This premise underlines the necessity of choosing the optimal treatment for each older patient according to their characteristics.

2. First-Line Treatment for Transplant-Ineligible Patients with Multiple Myeloma

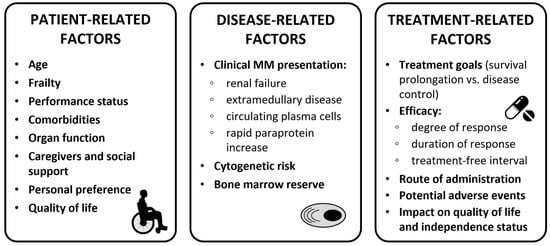

When selecting the best first-line treatment for older NDMM patients, several factors need to be considered: patient-related factors (e.g., age, frailty status, organ function, comorbidities, patient preference, and social status), disease-related factors (e.g., renal failure, presence of extramedullary disease [EMD], and presence of high-risk cytogenetics), and treatment-related factors (e.g., efficacy, treatment goals, potential AEs, and impact on quality of life; see Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Clinical considerations for treatment decision in transplant-ineligible patients. Abbreviations: MM, multiple myeloma.

Table 1.

Frailty subgroups and related outcomes in the ALCYONE and MAIA studies.

| MAIA [23][24][44,45] Dara-Rd FIT n = 68 |

ALCYONE [25][46] Dara-VMP FIT n = 48 |

MAIA [23][24][44,45] Dara-Rd INTER-MEDIATE n = 128 |

|---|

,45,48].

Table 2. Patient characteristics in studies evaluating first-line treatment for transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma.

| ALCYONE [22][43] | MAIA [24][45] | ALCYONE [25][46] Dara-VMP INTER-MEDIATE n = 139 |

SWOG S0777 [27][48] | MAIA [23][24][44,45] Dara-Rd FRAIL n = 172 |

Real MM [28][49] | ALCYONE [25][46] Dara-VMP FRAIL n = 163 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORR | 100% | 95.8% | 96.9% | 92.1 % | 87.2% | 88.3% | ||||||

| mPFS | NR | |||||||||||

| Age | Median (years) | 71 | 73 | 63 | 76 | |||||||

| NR | NR | 40.1 mo | NR | 32.9 mo | ||||||||

| ≥75 | 30% | 44% | >65 years: 43% | 55% | mDOT | 34.6 mo | 37.2 mo | 33.2 mo | 36.2 mo | 31.1 mo | ||

| ≥80 | 24.7 mo | |||||||||||

| 9% | 18.5% | Not reported | >80 years: 19% | Infections, G ≥ 3 | 23.5% | 12.5% | 35.9% | 27.5% | 41.7% | 30% | ||

| ECOG PS | 0–1 | 75% | 83% | 86% | 81% | Toxic deaths | 1.5% | 0 | 4.7% | 5.1% | 11.9% | 0 |

| 2 | 25% | 17% | 13% | Discontinuation due to PD | 20.6% | 2.1% | 19.5% | 5.8% | 18.6% | 8.8% | ||

| >2 | 0 | 0 | 2–3: 14%; >3: excluded | 6% | Discontinuation due to AEs | 7.4% | 2.1% | 7% | 4.3% | 9.9% | 6.9% | |

| Major exclusion criteria |

| |||||||||||

The RV-MM-PI-0752 study evaluated a steroid-sparing approach in intermediate-fit patients, comparing continuous Rd treatment (as administered in patients aged >75 years in the FIRST trial [15][22]) to 9 Rd induction cycles followed by lenalidomide maintenance at a lower dose (10 mg; Rd–R). Notably, in this setting of patients, no differences in PFS or OS were observed between the two treatment strategies, whereas event-free survival (EFS; including a combination of toxicity and efficacy) was significantly longer in the Rd–R arm. Furthermore, Rd–R resulted in better tolerability compared with Rd, particularly in terms of nonhematologic toxicity (grade ≥ 3, 33% vs. 43%) and lenalidomide dose reduction (45% vs. 62%) [34][55]. These results, together with results of other studies, may help to adapt standard treatment to frail patients, since de-escalation and early dexamethasone interruption do not have a negative impact on outcome.

Another steroid-sparing regimen was explored in NDMM patients who were determined to be frail according to age, comorbidities, and ECOG PS ≥ 2. The study compared Rd vs. daratumumab plus lenalidomide (DR), with only the first 2 cycles of dexamethasone. A preliminary analysis showed that ORRs were 77% vs. 89%, and that the 12-month rates of very good partial response (VGPR) or better were 42% vs. 58% in the Rd vs. DR arms, respectively. As compared with Rd, DR was associated with better rates of MRD negativity at 10−5 (3% vs. 10%). The rates of grade ≥ 3 infections and discontinuation were similar in both arms (16% in Rd vs. 13% in DR, not statistically significant). Awaiting longer follow-up and PFS data, this dexamethasone-sparing regimen with daratumumab has shown encouraging responses and good tolerability in this subset of frail patients [35][56].

Often, study results do not reflect the real-world population due to their strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. The ongoing noninterventional study MM-034 evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of lenalidomide (Len)-based (including Rd and VRd) and non-Len-based (including VMP) regimens in 890 NTE NDMM patients. Patients treated with lenalidomide showed a safety profile similar to those in pivotal trials. More patients discontinued therapy in non-Len-based cohorts than those in Len-based cohorts, and patients who had ≥1 dose adjustment had a longer median duration of response than those who did not. The Len-based cohort showed a nearly double mOS, as compared with the non-Len-based cohort, but patients who discontinued lenalidomide due to AEs experienced a significant worsening of mOS. These data showed that tolerability to treatment was critical for improving patient outcomes [36][57].

Several studies investigated therapeutic approaches guided by frailty evaluation. The phase II HOVON 143 trial investigated the combination of daratumumab, ixazomib, and low-dose dexamethasone (Ixa–Dara–dex) in NTE NDMM patients who were intermediate-fit and frail according to the IMWG frailty score. The ORR after induction was 71% and 78% in intermediate-fit and frail patients, with a mPFS of 17.4 and 13.8 months and a 12-month OS of 92% and 78%, respectively. Therapy discontinuation occurred in 51% of frail patients, 9% of whom discontinued due to toxicity and 9% of whom discontinued due to death (8% within 2 months, most of whom due to toxicity), while treatment discontinuation due to toxicity was 17% in intermediate-fit patients (6% interrupted the whole regimen, while 11% interrupted ixazomib only). Ixa–Dara–dex is, therefore, a feasible combination in older patients, although treatment discontinuation due to toxicity and early mortality negatively affected PFS and OS, consequently remaining a concern, especially in frail patients [37][38][58,59].

The ongoing FiTNEss (UK-MRA Myeloma XIV) trial is investigating a concept of frailty-adjusted dosing by incorporating a first-line treatment including ixazomib–lenalidomide–dexamethasone (Ixa–Rd). In the experimental arm, therapy is adjusted based on the IMWG frailty score, as compared with a non-frailty-adjusted induction in the control arm. The study is ongoing, and results are awaited to understand which approach is most effective and appropriate [39][28].

Ongoing studies are evaluating newer and more complex first-line combinations in NTE older patients (see Table 3).

Table 3. Ongoing trials with newer drug combinations for the treatment of transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma.

| Clinical Trials | Regimens | Phase | Primary Endpoints | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMROZ [40][60] | Isa–VRd vs. VRd | III | PFS | |||||

| EMN20 (NCT04096066) [41][61] | KRd vs. Rd | III | MRD negativity PFS |

|||||

| DREAMM-9 [42][43][62,63] | Belamaf VRd vs. VRd | III | MRD negativity PFS |

|||||

| MajesTEC-7 [44][64] | Tec–DR vs. DRd | III | MRD negativity PFS |

|||||

| Creatinine clearance | ||||||||

| 30–60 mL/min | 41% | 41% | 5% creat. >2 mg/dL | 40% | ||||

| Discontinuation due to noncompliance with the protocol | 1.5% | 0 | 3.9% | |||||

| <30 mL/min | 0.7% | Excluded | 4.7% | (<40 mL/min) | Excluded | 5.6% | ||

| Excluded | 9% | Median follow-up | 36.4 mo | 40.1 mo | 36.4 mo | 40.1 mo | 36.4 mo | 40.1 mo |

Abbreviations: Dara, daratumumab; R, lenalidomide; d, dexamethasone; V, bortezomib; M, melphalan; P, prednisone; ORR, overall response rate; mPFS, median progression-free survival; mDOT, median duration of treatment; G, grade; PD, progressive disease; AEs, adverse events; mo, months; NR, not reached.

However, choosing the most appropriate regimen between D–VMP and D–Rd can be challenging due to the lack of comparison data. Furthermore, the studies that led to the registration of these two combinations included patients with a median age of 73 and 71 years who met specific inclusion criteria. The ongoing Real MM study aims to overcome these limitations. In the first version of the study, real-life, unselected NTE NDMM patients were enrolled and randomized 1:1 to either VMP or Rd. Following the widespread adoption of daratumumab as the backbone of first-line therapy in older patients, the Real MM study was amended to randomize patients to D–VMP vs. D–Rd. Preliminary data on the first 250 patients treated with VMP vs. Rd showed no differences in terms of mPFS (29.6 vs. 26.3 months, HR 0.82, p = 0.41), while VMP showed a prolonged mPFS in high-risk patients, as compared with Rd (not reached [NR] vs. 13.3 months, HR 0.22). There was no difference in terms of PFS according to frailty status (calculated using the IMWG frailty score). Adjusted dose upfront and during treatment did not affect efficacy, particularly in the subgroup of frail patients [26][47]. Additional analysis is needed to determine whether these results are confirmed in terms of OS and whether, as expected, the addition of daratumumab will have an impact on efficacy in all patients and specific subgroups, such as high-risk and frail patients. Unlike many trials investigating the current standards of care, the Real MM trial includes an unselected population, making its results valuable in identifying patients or subgroups that would benefit from this type of therapy (see Table 2) [22][24][27][43

| ||||

|

|

|

|

Abbreviations: R, lenalidomide; d, dexamethasone; V, bortezomib; M, melphalan; P, prednisone; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; creat., creatinine; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; ULN, upper limit of normal; NYHA, New York Heart Association classification.

In a subanalysis of the Real MM trial on health-related (HR)QoL, VMP treatment was associated with a worse HRQoL compared with Rd. VMP showed a transitory decrease in HRQoL, especially during the early treatment cycles, with an improvement from approximately the sixth month of therapy. In particular, during the twice-weekly bortezomib schedule, VMP was associated with temporary worsening in physical functioning, nausea, appetite, and fatigue. Depth of response did not seem to predict HRQoL in this cohort of real-life NTE MM patients, while frail patients showed relatively lower and long-lasting HRQoL compared with fit patients. The data collected after adding daratumumab will be useful in assessing the impact of treatment on QoL in different subgroups of patients treated with standard-of-care regimens [29][50].

In April 2019, the EMA approved VRd in NTE NDMM patients older than 65 years based on the results of the SWOG S0777 trial, which showed significantly better PFS (43 vs. 30 months, HR 0.71) and OS (75 vs. 64 months, HR 0.70) with the VRd triplet vs. Rd. In the multivariate analysis, the impact of both the treatment groups was retained regardless of age and intent to transplant. These differences were statistically significant for patients aged <65 years and >75 years. However, in the VRd group, the median OS (mOS) was 65 months in patients aged >65 years vs. NR in patients aged <65 years. Similarly, in the Rd group, median OS was 56 months in patients >65 years vs. 98 months in those aged <65 years. Furthermore, as expected, the incidence of grade 3–4 toxicities was higher in the VRd arm (82% vs. 75%), particularly in the case of grade 3–4 peripheral neuropathy (11% vs. 3%) [5]. In the extended 7-year follow-up, the advantage of VRd vs. Rd in terms of PFS (41 vs. 29 months for Rd) and OS (NR vs. 69 months) was confirmed [27][48].

A modified version of VRd (VRd-lite) was investigated in a phase II study in NTE patients. The lenalidomide dose was reduced to 15 mg/day, and bortezomib was administered weekly. The median age of the patient population was 73 years, the ORR was 86% with a mPFS of 41.9 months, and treatment was better tolerated, with 2% of grade 3–4 neuropathy. These results suggest that VRd-lite may be a suitable and feasible option for older MM patients [30][31][51,52].

In the absence of a head-to-head comparison of different treatment sequences in the new treatment landscape for MM, a study by Fonseca et al. explored different clinical scenarios to determine the clinical value of using daratumumab in NTE NDMM patients in the first-line setting or of saving it for subsequent lines of therapy. The researchers compared two different therapy sequencing strategies: (1) D–Rd upfront followed by a pomalidomide- or carfilzomib-based approach at relapse; (2) VRD/Rd upfront followed by a daratumumab-based combination at relapse. D–Rd in first-line treatment improved mOS by 2 years compared with delaying daratumumab-based regimens until the second line after VRd failure (mOS 8.9 vs. 6.9 years) and by 3.2 years after Rd failure (mOS 8.9 vs. 5.75 years). Moreover, a higher probability of being alive at 5, 10, and 15 years was associated with first-line D–Rd, as compared with first-line VRd or Rd. These data suggest the importance of first-line therapy and confirm that achieving the longest possible PFS in first-line therapy drives survival outcomes [32][53].

Due to the large heterogeneity of older MM patients, a personalized treatment approach according to patient frailty status may be considered. In particular, frail patients may benefit from a gentler approach. The EMN01 study stratified patients according to the IMWG frailty score and showed no differences in terms of PFS and OS in NTE intermediate-fit and frail patients who received Rd vs. melphalan–prednisone–lenalidomide (MPR) vs. cyclophosphamide–prednisone–lenalidomide (CPR). In contrast, fit patients had better outcomes with the MPR triplet (HR 0.72 for PFS of MPR vs. Rd). Thus, the study showed that fit patients could benefit from a triplet, whereas frail patients could benefit from less intensive treatments [33][54].

Abbreviations: Isa, isatuximab; V, bortezomib; R, lenalidomide; d, dexamethasone; Belamaf, belantamab mafodotin; Tec, teclistamab; D, daratumumab; PFS, progression-free survival; MRD, minimal residual disease negativity.

Encyclopedia

Encyclopedia