Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Jeremy Lamri.

The distinction between hard and soft skills has long been a topic of debate in the field of psychology, with hard skills referring to technical or practical abilities, and soft skills relating to interpersonal capabilities.

- skills

- soft skills

- hard skills

- cognition

- conation

1. Introduction

In today’s complex, interconnected world, the importance of having a diverse set of skills for success is undeniable. The ability to define, develop and utilise one’s skills is considered a vital part of personal and professional success. This success depends heavily on the acquisition and maintenance of both soft and hard skills. In the modern workforce, employers are searching for the perfect candidate, the one who can bring a combination of skills to the table. Indeed, skills can generally be divided into two main categories—hard skills and soft skills. Hard skills refer to technical or practical abilities, such as programming languages, engineering, accounting, and other occupational skills, whereas soft skills are interpersonal capabilities, such as communication, problem-solving, and emotional intelligence (Cimatti 2016; Laker and Powell 2011).

Although these two types of skills are often categorised separately, it is important to understand their interdependence, as well as their contributions to certain areas of expertise. In recent years, there has been increasing recognition of the importance of soft skills in many areas, including education and business (Andrews and Higson 2008; Succi and Canovi 2020). The so-called “soft skill revolution” has seen a growing interest in developing and assessing these skills, as organisations have become increasingly aware of their value in the workplace. Yet, there is still some debate about what constitutes a soft skill, and to what extent hard skills remain essential for success. Despite the acknowledged value of soft skills, the lack of a standard definition or systematic approach to measuring and assessing these skills poses a challenge when attempting to review and compare them (Dede 2010; Robles 2012; Rasipuram and Jayagopi 2020).

Even before challenging the concept of soft skills, there is the question of what a “skill” is, and how to develop certain skills, as it remains an ongoing area of research for psychologists and educators. Whereas the study of skills has traditionally been associated with individual traits such as intelligence and talent, an emerging field of inquiry suggests that the composition of any skill is made up of several core elements. Overall, skills are an important foundation for development, yet much research is needed to understand better the generic components of skills. Although soft skills and hard skills seem very different in the way they are used and observed, what actually makes them inherently different? If both are actually skills, they may have more in common than it seems. In recent years, research into the generic composition of any skill, and the relationship between soft skills and hard skills, has gained increased interest due to its implications for workplace productivity.

Researchers have identified that any workplace skill requires a combination of hard and soft skills (van der Vleuten et al. 2019; Lyu and Liu 2021). They have also elucidated that there are shared components between hard and soft skills which could be seen as the bridge between them (Pieterse and Van Eekelen 2016; Kuzminov et al. 2019). This presents an interesting opportunity for educators and trainers to develop individuals in an integrated manner, allowing for an understanding of both technical and non-technical components of skills.

2. From Skills Theories to the Generic Skills Component Approach

2.1. Foundations for the Generic Skill Components Approach

Is the distinction between hard/soft useful? Is there, metaphorically, a scale of “hardness” of skills, like Mohs’ scale for the hardness of minerals, ranging from talc (very soft) to diamonds (very hard)? Numerous authors have raised the idea of a continuum from hard to soft skills passing by a vast mid-scale with semi-hard and semi-soft skills (see Andrews and Higson 2008; Clarke and Winch 2006; Dell’Aquila et al. 2017; Hendarman and Cantner 2018; Lyu and Liu 2021; Spencer and Spencer 1993; Rychen and Salganik 2003). Le Boterf (2000) suggests that skills are better understood as a continuum, with some skills containing both hard and soft components. The generic skill components approach builds upon these recent findings, suggesting that all skills can be understood through a shared framework of five distinct components: knowledge, active cognition, conation, affection, and sensory-motor abilities. This integrated approach has the potential to reconcile the traditional distinction between hard and soft skills, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the complex nature of skills and their development.2.2. Discrediting Skills as Discrete Entities

Working on a generic structure for all skills implies that skills are not discrete entities as such. WResearchers believe there is a necessity to clarify that aspect, before moving towards the construction of a generic skills approach. Consider the following arguments: 1. Overlapping and interrelated nature of skills: Skills are often interconnected and interdependent, making it difficult to clearly separate them into distinct categories. For example, the successful application of technical skills often depends on the presence of effective interpersonal skills, and vice versa (Kavé and Yafé 2014; Gardiner 2017). This overlap and interrelatedness challenges the idea that skills exist as discrete entities (Greenwood et al. 2013; Bean et al. 2018). 2. Contextual factors: The relevance and importance of specific skills can vary depending on the context in which they are applied. This contextual variability can lead to differing interpretations and classifications of skills, further challenging the idea of skills as discrete and stable entities (Perkins and Salomon 1989; Hall and Magill 1995; Widdowson 1998). 3. Evolving skill requirements: The rapidly changing nature of work and technological advancements requires individuals to adapt continuously and develop new skills. As a result, the boundaries between different skill categories may become increasingly blurred as individuals are expected to possess a diverse and dynamic skillset (Dede 2010; Hargood and Peckham 2017; Dominici 2019). 4. Limitations of terminologies: The use of specific terminologies for hard and soft skills can sometimes oversimplify or constrain ourthe understanding of the multidimensional nature of skills. By focusing on specific aspects or dimensions of skills, these terminologies may inadvertently perpetuate the idea that skills are discrete entities, rather than acknowledging the complex, interconnected permeable nature of skill development and application (Matteson et al. 2016; Lyu and Liu 2021). The overlapping and interrelated nature of skills, the continuum perspective, contextual factors, evolving skill requirements, and the limitations of terminologies contribute to the difficulty of treating skills as discrete entities. Recognising these challenges can help researchers and practitioners develop more nuanced and integrative approaches to skill development and assessment. Building on this analysis, wresearchers believe there is a need for a unified approach to the structure of skills.2.3. Using Goldstein and Hilgard’s Work as a Core Basis

The ambition to find a generic structure for skills is not new. Goldstein (1989) proposed a framework, with four components structuring any skill: cognitive, affective, motivational, and behavioural. In Goldstein’s, cognitive components involve the understanding and knowledge associated with a skill, such as problem-solving and analytical skills. Affective components involve emotions and attitudes, such as self-awareness and empathy. Motivational components involve the drive and determination to succeed, such as perseverance and ambition. Last, behavioural components involve the actual physical performance of a skill, such as hand-eye coordination and agility. Although the literature is filled with definitions and discussions about skills, wresearchers choose in this article to use the work of Goldstein (1989) as a primary basis. His work, both theoretical and empirical, provides a comprehensive framework for understanding, designing, implementing, and evaluating skills development in organisations. Applying these four components to hard and soft skills, wresearchers can see that all skills are composed of the same elements, but with different weights depending on the context in which they are used. For example, a hard skill such as programming would require a higher level of cognitive ability but lower levels of affection. In contrast, a soft skill such as active listening would require a higher level of affection but lower levels of cognition. In that way, Goldstein’s framework seems a relevant basis to reconcile soft skills and hard skills. However, it is necessary to take a step back and take a closer look at Goldstein’s components. Goldstein’s work relates to Hilgard’s (1980a) ‘Trilogy of Mind’, which describes human consciousness in terms of three main dimensions: cognition, conation, and affection. Hilgard (1975, 1980b, 1986) examines learning, personality, and hypnosis, and how they interact with one another to shape ourthe understanding of the mind. Hilgard’s trilogy is itself based on the ‘Trilogy of Mind’ that Emmanuel Kant espoused. Hilgard’s conception of these concepts differs from Goldstein’s:- An explanation of the importance given to each component in the context of the skill;

- A suggestion of a training program detailed for each component.

- (A)

-

Example 1: Oral communication

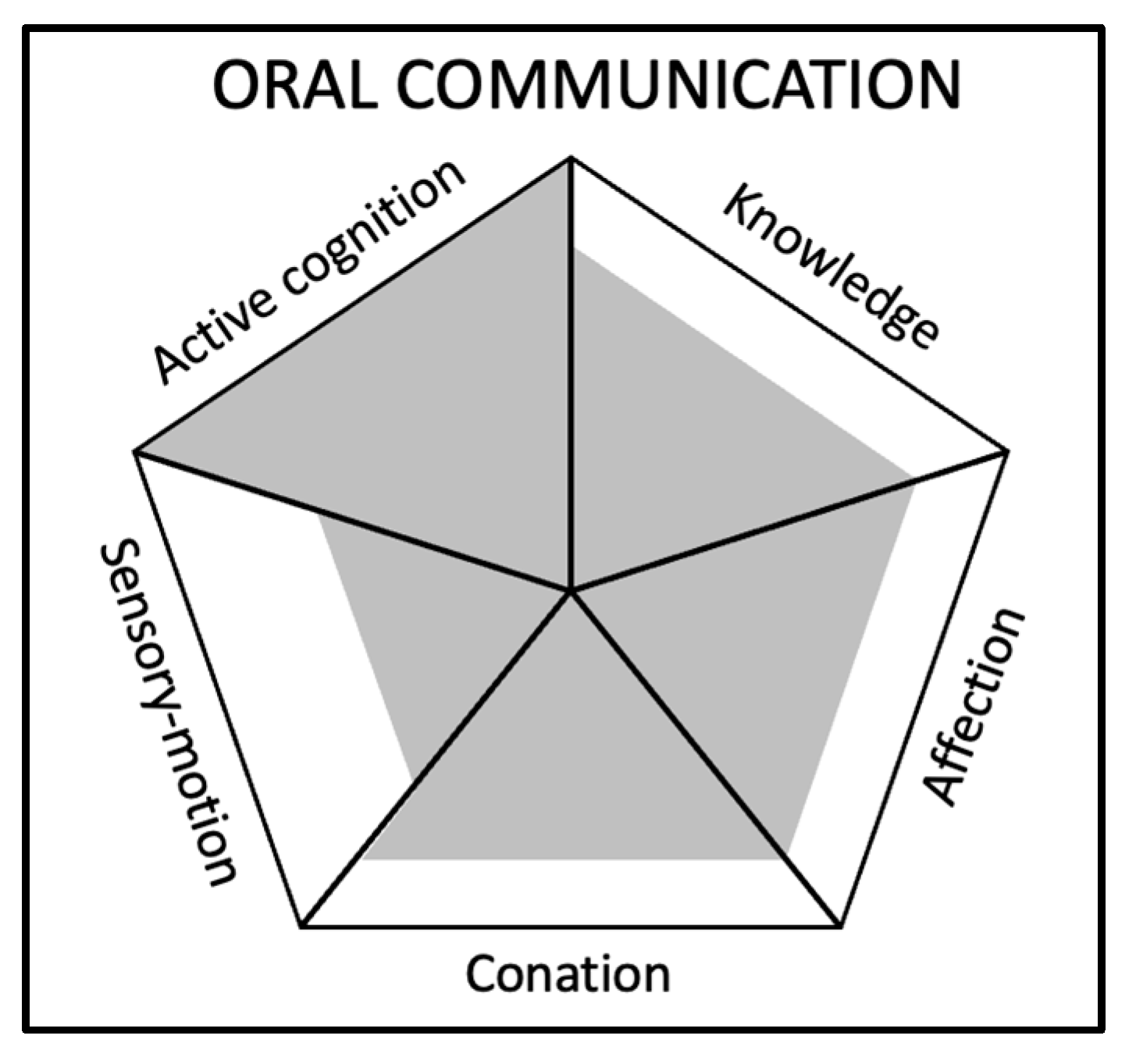

Figure 2. Visual representation of the generic skills components’ framework for the skill ‘Oral communication’.

Figure 2. Visual representation of the generic skills components’ framework for the skill ‘Oral communication’.-

Knowledge: 4/5—Knowledge is essential for effective oral communication, as it involves understanding the topic being discussed, the context, and the audience. Having a solid grasp of the subject matter, as well as cultural and social norms, allows the speaker to convey messages accurately and effectively. Additionally, internal knowledge helps the speaker to convey relevant information and experiences to support their points.

-

Knowledge:

-

Provide learners with the necessary knowledge related to the subject matter they will be communicating, whether it is through lectures, research, or reading.

-

Encourage learners to integrate this knowledge into their communication to increase their credibility and effectiveness.

-

-

Active cognition: 5/5—Active cognition is crucial for oral communication, as it involves perceiving and processing information in real-time. Effective oral communication requires the speaker to pay attention to the audience, adapt the message based on audience reactions, and make judgments about what information to share and how to present it. It also involves critical thinking and problem-solving skills, as the speaker may need to respond to questions or objections from the audience.

-

Active cognition:

-

Provide learners with opportunities to practise active listening and critical thinking to understand better the needs of their audience and adapt their communication accordingly.

-

Encourage learners to use visual aids or other communication tools to increase their impact and effectiveness.

Conation: 4/5—Trait extraversion can support oral communication because it motivates the speaker to engage with the audience and present the message confidently and persuasively. A strong willingness to act can also help the speaker overcome any anxiety related to speaking in front of others. -

-

Affection: 4/5—The ability to empathise with and manage emotions is important for connecting with the audience and creating a positive atmosphere during oral communication. Understanding the emotional state of the audience can help the speaker adjust their/his/her tone and approach while managing their/his/her own emotions can ensure a calm and composed delivery. Additionally, being able to express warmth and enthusiasm can make the message more engaging and persuasive.

-

Sensory motor abilities: 3/5—Although not as critical as other components, sensory-motor abilities still play a role in oral communication. The ability to control and coordinate movements, such as gestures and facial expressions, can help the speaker convey a message more effectively and make a stronger impression on the audience. Proper posture, eye contact, and voice modulation are also important aspects of oral communication that rely on sensory-motor abilities.

- Conation:

-

-

Provide learners with opportunities to practise oral communication in a safe and supportive environment, such as through role-playing or group discussions.

-

Encourage learners to take risks and learn from their mistakes, building their confidence and willingness to communicate effectively.

-

- Cognition is the ability to think and solve problems, acquire information, and understand the world around us. It entails the processing of ideas and facts which allows the user to make better-informed decisions.

- Conation is the preferred pattern of actions and choices, integrating the results of cognitive processes to take action in order to achieve

- our

- the

- objectives. It relies on the capacity to plan, as well as to monitor and evaluate ourthe goal-driven performance.

-

Affection is the ability to build and maintain relationships with others, stimulating social interaction and facilitating collaborative work. It involves the capacity to understand and empathise with others’ needs, as well as the ability to develop positive social networks.

-

Knowledge includes both external knowledge or facts, such as technical job-related knowledge, as well as internal knowledge, such as memory (Bloch 2016; Zagzebski 2017).

-

Active cognition involves perceiving and processing information to form decisions and opinions, such as perception, attention, and judgement (Bickhard 1997). The analysis of the environment and the context falls under active cognition.

-

Conation is the component that describes preferences, motivations, and volitional components of behaviour. It is the drive or impulse to act and is often referred to as the “will” or “willingness” to act (Csikszentmihalyi 1990). WResearchers believe it goes beyond motivation as referred to by Goldstein.

-

Affection: Affection is the ability to empathise with and manage feelings in order to build and maintain relationships with others.

-

Sensory motor abilities: Sensory motor abilities refer to the ability to control and coordinate movements. This includes the ability to perceive, interpret, and respond to sensory input, as well as the ability to plan and execute movements. Examples of sensory-motor abilities include balance, coordination, and fine motor skills.

2.4. Developing the Generic Skill Components Approach

The generic skill components approach aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the structure and composition of any skill. This approach posits that all skills, whether hard or soft, can be understood in terms of five distinct components: knowledge, active cognition, conation, affection, and sensory-motor abilities. By examining these components and their interactions, wresearchers can gain a more in-depth understanding of the nature of skills and their development. This approach is supported by previous research that has identified common elements across various types of skills. For example, Rychen and Salganik (2003) propose a model of key competencies that includes cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal dimensions, which align with the active cognition, conation, and affection components of the generic skill components approach. Similarly, other studies highlight the importance of cognitive, affective, and behavioural processes in the development and application of both hard and soft skills (Parlamis and Monnot 2019; Soto et al. 2022). OurThe approach extends beyond existing models by incorporating sensory-motor abilities, which are often overlooked in discussions of skill development. This inclusion acknowledges the importance of physical and perceptual abilities in the successful application of many skills, particularly in fields such as sports, manufacturing, and healthcare. This approach has several potential applications and implications for various fields, including education, training, and management. By understanding the generic components of skills, educators and trainers can develop more effective and holistic approaches to skill development, integrating both technical and non-technical components. In the workplace, a greater understanding of the generic composition of skills can help inform hiring decisions, performance evaluations, and employee development programs. If a skill has a major active cognition component, the resulting pedagogic engineering will be very different compared to a skill with a major knowledge component. Further research is needed to refine and expand upon the generic skill components approach. Future studies could explore the interactions between the different components, as well as the impact of contextual factors on skill development and use. Indeed, the generic skill components approach highlights the importance of context in the development and application of skills, suggesting that educators and trainers should consider the specific environments in which their students or employees will be applying their skills. This may require the development of more context-specific training programs that focus on the unique challenges and opportunities presented by different work environments. Additionally, researchers could investigate the potential for more distinct skill categories and their implications for various domains.2.5. Tentative Representation of the Generic Skills’ Components Framework

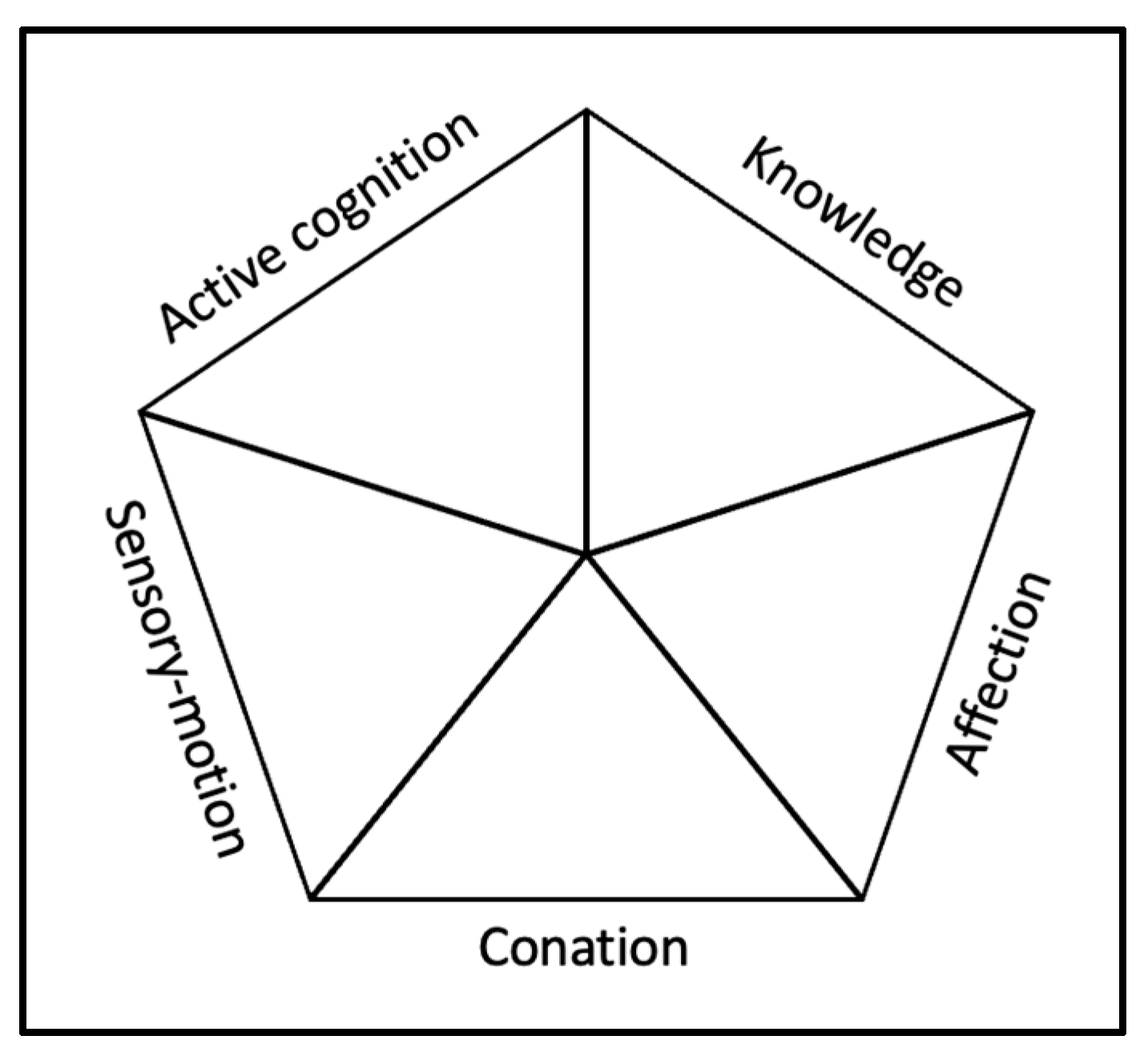

Although the approach needs to be further developed and tested empirically, wresearchers propose in this articleresearch an attempt at visual representation, displaying the five generic components in a diagram (see Figure 1). This diagram may be seen as a template to be used for skills description, as proposed later.The understanding of generic skills components would be that all components exist independently and need to be associated to create the necessary skill. This implies that they are not relative to each other, meaning that for a given skill, it is possible that all components are required at a very high level of mastery or development. Furthermore, conversely, for another skill, it is possible that all components are required at a very low level. In this manner, all types of combinations are possible, the point being that the necessity of one component at a high level does not determine the level of other components. Figure 1. Visual representation of the generic skills’ components framework.

Figure 1. Visual representation of the generic skills’ components framework.2.6. Tentative Representation of Skills Composition Using the Framework

Below, wresearchers propose three examples of using the framework to represent skills: oral communication, Python programming, and logical analysis. At this stage, the assessment is very basic, as it results in a consensus among the authors, having both theoretical and empirical experience in skills expertise. These specific cases of skill descriptions will need to be challenged in order to be considered consensual, but the purpose of this section is rather to show the possibilities offered by the generic skills’ components approach. For each skill, weresearchers propose:-

A visual representation based on the generic skills’ components framework (see Figure 1);

-

A rating from 1 (low) to 5 (high) for each component;

-

- Affection:

-

Integrate exercises and activities that promote empathy and emotional intelligence, such as reflecting on the emotional impact of communication or practising active listening.

-

Encourage learners to build positive relationships with their audience, as this can enhance their effectiveness as communicators.

-

-

Sensory motor abilities:

-

Provide learners with opportunities to practise their oral communication skills, such as pronunciation, articulation and voice projection exercises.

-

Encourage learners to practise clear and effective body language to enhance their overall communication skills.

-

- (B)

-

Example 2: Python programming

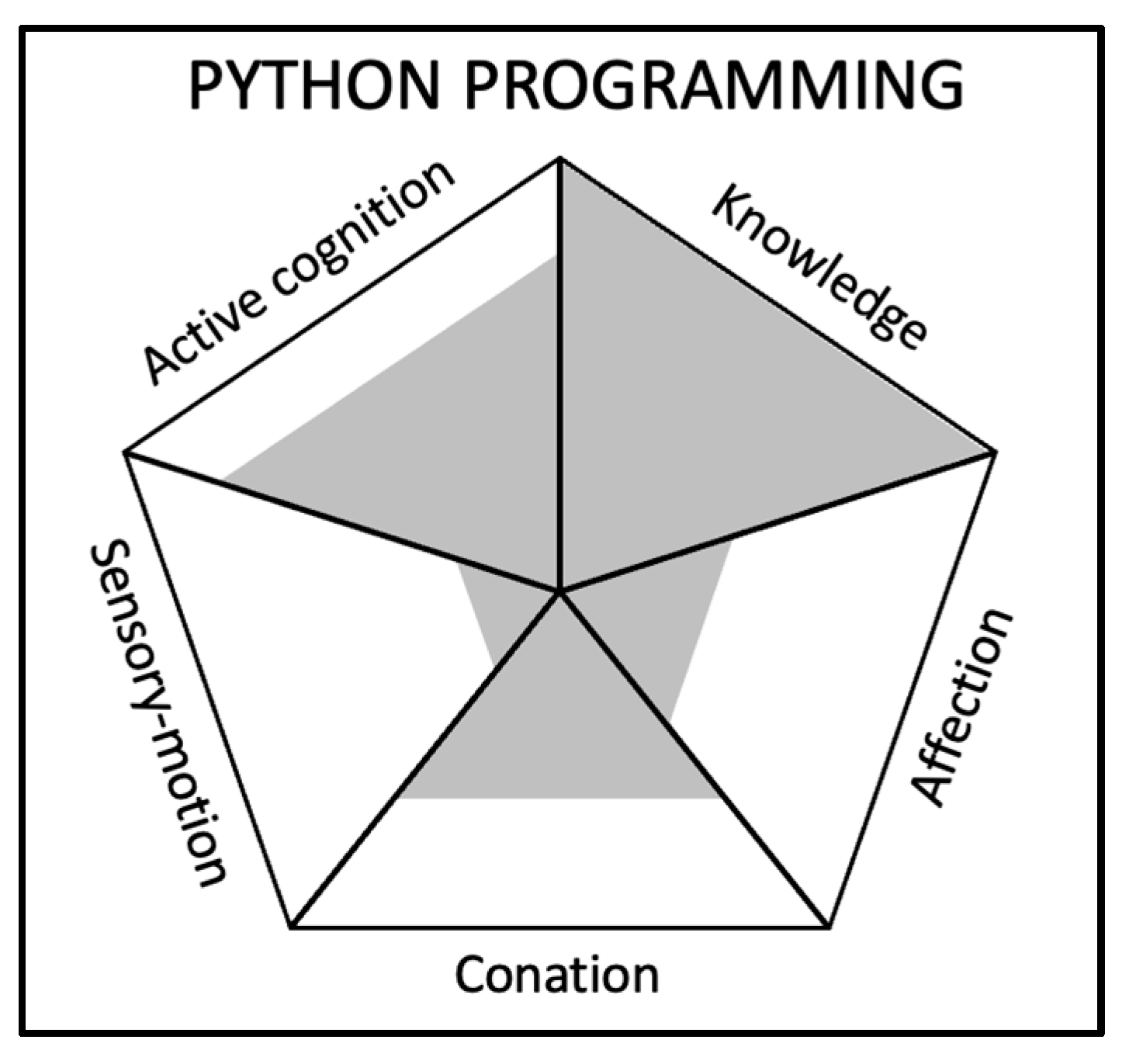

Figure 3. Visual representation of the generic skills’ components framework for the skill “Python programming”.

Figure 3. Visual representation of the generic skills’ components framework for the skill “Python programming”.-

Knowledge: 5/5—Knowledge is crucial for Python programming, as it involves understanding the syntax, functions, libraries, and best practices in the language. A programmer must be knowledgeable about programming concepts, algorithms, and data structures to effectively use Python in various applications. This includes both external knowledge, such as learning from resources and documentation, and internal knowledge, such as remembering previously learned concepts and experiences.

-

Active Cognition: 4/5—Active cognition plays an important role in Python programming, as it involves perceiving and processing information to form decisions and opinions. This includes understanding the problem being solved, designing an appropriate solution, and troubleshooting any issues that arise during coding. Active cognition also involves adapting to new programming paradigms, tools, and techniques.

-

Conation: 3/5—Conation is moderately important in Python programming. Although having the motivation and willingness to learn and improve one’s programming skills is important, it may not be the primary driver for success in this field. However, showing perseverance, and having a strong drive to problem-solve, debug, and optimise code can contribute to better overall performance and growth as a programmer.

-

Affection: 2/5—Affection has a lower importance in Python programming compared to other components. While empathy and emotional intelligence may not directly contribute to programming skills, they can still play a role in building positive relationships with teammates or clients, understanding user needs, and contributing to a healthy work environment. Good communication and collaboration skills can also help when working on projects with others.

-

Sensory Motor Abilities: 1/5—Sensory motor abilities have minimal importance in Python programming. While basic motor skills are needed for typing and using a computer, the primary focus in programming is on cognitive and knowledge-based skills. However, maintaining proper ergonomics and posture while working at a computer can help prevent physical strain and promote overall well-being.

It is interesting to observe that using the framework, it appears that active cognition and knowledge seem to be the most important components for the skill of Python programming. However, conation is not to be underestimated. Knowledge is commonly associated with hard skills, whereas active cognition and conation are commonly associated with soft skills. Although knowledge seems more important than the other components, wresearchers believe the importance of other components is generally underestimated when considering Python programming as a hard skill, as context matters. This example shows value for such skills that are unfairly considered hard skills with little to no consideration for the potential complexity of the context, or the motivation of the programmer.

References

- Cimatti, Barbara. 2016. Definition, development, assessment of soft skills and their role for the quality of organizations and enterprises. International Journal for Quality Research 10: 97.

- Laker, Dennis R., and Jimmy L. Powell. 2011. The differences between hard and soft skills and their relative impact on training transfer. Human Resource Development Quarterly 22: 111–22.

- Andrews, Jane, and Helen Higson. 2008. Graduate employability, ‘soft skills’ versus ‘hard’ business knowledge: A European study. Higher Education in Europe 33: 411–22.

- Succi, Chiara, and Magali Canovi. 2020. Soft skills to enhance graduate employability: Comparing students and employers’ perceptions. Studies in Higher Education 45: 1834–47.

- Dede, Chris. 2010. Comparing frameworks for 21st century skills. 21st Century Skills: Rethinking How Students Learn 20: 51–76.

- Robles, Marcel M. 2012. Executive perceptions of the top 10 soft skills needed in today’s workplace. Business Communication Quarterly 75: 453–65.

- Rasipuram, Sowmya, and Dinesh B. Jayagopi. 2020. Automatic multimodal assessment of soft skills in social interactions: A review. Multimedia Tools and Applications 79: 13037–60.

- van der Vleuten, Cees, Valerie van den Eertwegh, and Esther Giroldi. 2019. Assessment of communication skills. Patient Education and Counseling 102: 2110–13.

- Lyu, Wenjing, and Jin Liu. 2021. Soft skills, hard skills: What matters most? Evidence from job postings. Applied Energy 300: 117307.

- Pieterse, Vreda, and Marko Van Eekelen. 2016. Which are harder? Soft skills or hard skills? Paper presented at ICT Education: 45th Annual Conference of the Southern African Computer Lecturers’ Association, SACLA 2016, Cullinan, South Africa, July 5–6; Revised Selected Papers. Cham: Springer International Publishing, vol. 45, pp. 160–67.

- Kuzminov, Yaroslav, Pavel Sorokin, and Isak Froumin. 2019. Generic and specific skills as components of human capital: New challenges for education theory and practice. Фoрсайт 13: 19–41.

- Clarke, Linda, and Christopher Winch. 2006. A European skills framework?—But what are skills? Anglo-Saxon versus German concepts. Journal of Education and Work 19: 255–69.

- Dell’Aquila, Elena, Davide Marocco, Michela Ponticorvo, Andrea Di Ferdinando, Massimiliano Schembri, and Orazio Miglino. 2017. Soft Skills. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–18.

- Hendarman, Achmad F., and Uwe Cantner. 2018. Soft skills, hard skills, and individual innovativeness. Eurasian Business Review 8: 139–69.

- Spencer, Lyle M., and Stacy M. Spencer. 1993. Competence at Work: Models for Superior Performance. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Rychen, Dominique S., and Laura H. Salganik, eds. 2003. Key Competencies for a Successful Life and a Well-Functioning Society. Gottingen: Hogrefe Publishing.

- Le Boterf, Guy. 2000. Construire les Compétences Individuelles et Collectives. Paris: Éditions d’organisation.

- Kavé, Gitit, and Ronit Yafé. 2014. Performance of younger and older adults on tests of word knowledge and word retrieval: Independence or interdependence of skills? American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 23: 36–45.

- Gardiner, Paul. 2017. Playwriting and Flow: The Interconnection Between Creativity, Engagement and Skill Development. International Journal of Education and the Arts 18: 1–24. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/sspapers/4678/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Greenwood, Charles R., Dale Walker, Jay Buzhardt, Waylon J. Howard, Luke McCune, and Rawni Anderson. 2013. Evidence of a continuum in foundational expressive communication skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 28: 540–54.

- Bean, Corliss, Sara Kramers, Tanya Forneris, and Martin Camiré. 2018. The implicit/explicit continuum of life skills development and transfer. Quest 70: 456–70.

- Perkins, David N., and Gavriel Salomon. 1989. Are cognitive skills context-bound? Educational Researcher 18: 16–25.

- Hall, Kellie G., and Richard A. Magill. 1995. Variability of practice and contextual interference in motor skill learning. Journal of Motor Behaviour 27: 299–309.

- Widdowson, Henry G. 1998. Skills, abilities, and contexts of reality. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 18: 323–33.

- Hargood, Charlie, and Stephen Peckham. 2017. Soft Skills for the Digital Age. London: Routledge.

- Dominici, Piero. 2019. Educating for the Future in the Age of Obsolescence. Paper presented at 2019 IEEE 18th International Conference on Cognitive Informatics & Cognitive Computing (ICCI* CC), Milan, Italy, July 23–25; pp. 278–85.

- Matteson, Myriam L., Lorien Anderson, and Cynthia Boyden. 2016. “Soft skills”: A Phrase in Search of Meaning. portal Libraries and the Academy 16: 71–88.

- Goldstein, Irwin L. 1989. Training and Development in Organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Hilgard, Ernest R. 1980a. The trilogy of mind: Cognition, affection, and conation. Journal of the History of the Behavioural Sciences 16: 107–17.

- Hilgard, Ernest R. 1975. Theories of Learning. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

- Hilgard, Ernest R. 1980b. Theories of Personality. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

- Hilgard, Ernest R. 1986. Theories of Hypnosis. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

- Goleman, Daniel. 1995. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. New York: Bantam Books.

- Bloch, Maurice. 2016. Internal and external memory: Different ways of being in history. In Tense Past. New York: Routledge, pp. 215–33.

- Zagzebski, Linda. 2017. What Is Knowledge? The Blackwell Guide to Epistemology. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 92–116.

- Bickhard, Mark H. 1997. Piaget and active cognition. Human Development 40: 238–44. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26767639 (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 1990. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper Perennial.

- Parlamis, Jennifer, and Matthew Monnot. 2019. Getting to the CORE: Putting an end to the term “Soft Skills”. Journal of Management Inquiry 20: 225–27.

- Soto, Christopher J., Christopher M. Napolitano, Madison N. Sewell, Hee J. Yoon, and Brent W. Roberts. 2022. An integrative framework for conceptualizing and assessing social, emotional, and behavioural skills: The BESSI. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 123: 192.

More