You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Elias Ghabouli and Version 2 by Camila Xu.

Brownfields refer to sites that have been previously utilized or developed and are currently abandoned, idle, or inadequately used. In addition to their potential for rehabilitation, brownfields offer cultural and historical importance. Hence, moreover physical preservation, the building’s authenticity should be preserved by assigning suitable functions. In other words, intangible aspects such as social activities, collective memories, and meanings should be considered alongside tangible heritage to define the site’s unique identity and strengthen the sense of belonging.

- urban regeneration

- brownfield

- heritage

- public perception

- Tehran

1. Introduction

Brownfields refer to sites that have been previously utilized or developed and are currently abandoned, idle, or inadequately used. While not all brownfields are contaminated, they may suffer from soil and groundwater contamination that requires intervention to return them to beneficial use [1][2][3][1,2,3]. Brownfields have diverse origins and histories. Despite their presence in both rural and urban areas, they present a significant concern specifically within urban environments [2][4][5][2,4,5]. Brownfields hinder urban growth but offer unrealized potential [6]. Brownfield regeneration supports urban development [1][7][1,7] and promotes sustainable development through environmental, social, and economic benefits [8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Cities widely adopt urban regeneration to improve physical, economic, social, and environmental conditions by revitalizing urban areas [18][19][20][18,19,20]. As a specific type of urban regeneration, brownfield regeneration has the potential to address challenges in cities and further the objectives of urban regeneration [17][21][22][17,21,22]. Cities are now implementing innovative approaches for urban regeneration, such as culture-based and tourism-based strategies that exploit cultural assets for generating tourism while improving economic growth and social cohesion [23][24][25][23,24,25]. The transformation of brownfields into novel spaces has the potential to promote cultural events, recreational pursuits, and tourism attractions [20][26][27][28][20,26,27,28].

In addition to their potential for rehabilitation, brownfields offer cultural and historical importance [4]. By taking into account heritage preservation, sustainable brownfields regeneration may be accomplished [28][29][30][28,29,30]. The stagnation created by these sectors may be transformed into economic development [26][27][28][26,27,28] via the preservation of historical buildings and the utilization of heritage brownfields for tourism and recreation. In addition, heritage sites are major physical landmarks that have emotional and communal importance in modern culture, serving as memory triggers. The city’s reputation and the sense of community may both benefit from their transformation into tourism destinations [31][32][31,32]. Brownfields are being maintained and used for regeneration as the idea of heritage receives more attention. However, there is often a conflict between heritage preservation and economic interests, and heritage preservation is not always given top priority [33][34][33,34]. The regeneration of brownfields thus requires special consideration for heritage preservation.

In the last two decades, Iran's production, particularly in smaller industries, has significantly declined. Moreover, due to economic sanctions and political tensions with the West, the abandonment of diverse industries has rapidly increased [35]. The lack of a definite legal definition for brownfields in Iran [35][36][37][38][35,36,37,38] has led to their continued disuse. Only 8% of Iran’s many abandoned sites are utilized, and 24% are at risk of being demolished [39]. The heritage problem of Iranian brownfields hence needs careful consideration. The public may be made aware of the importance of redeveloping these regions through their preservation, which can also strengthen historical and regional identity.

2. Urban Brownfields and Public Perception

Urban brownfields have a notable impact on urban development and structures [6]. Brownfields may be abandoned and contaminated after being used for economic activities [2][40][2,40]. Environmental pollution heightens anxiety, worsens health risk perceptions [41], and reduces economic value and nearby attractions [1][28][1,28]. Revitalizing brownfields positively affects nearby communities and inhabitants [42][43][44][45][46][47][42,43,44,45,46,47]. Hence, these sites garner local interest [6][42][6,42], making it crucial to involve residents as primary stakeholders in developing regeneration strategies [44]. Therefore, sustainable regeneration should strengthen public participation and prioritize local perspectives [13][48][49][13,48,49]. Moreover, the vital role of residents’ opinions in brownfield regeneration has been highlighted by various studies such as those by Bartke and Schwarze [50], Glumac et al. [51], Haase [52], Johnson et al. [53], Meyer and Lyons [54], and Navratil et al. [55]. However, the residents’ views in practical projects have received scant attention [56], and market demands and public sector interests typically take precedence over meeting community needs during the reuse process [57]. Therefore, public support is crucial for brownfield projects [58][59][58,59]. Differences exist between the viewpoints of people and experts [2][13][51][60][61][2,13,51,60,61], and planners need to comprehend local attitudes towards brownfield types, reuse strategies, and planning procedures to foster societal participation [59]. People have diverse perceptions and priorities concerning brownfields [58][62][58,62], resulting in varying satisfaction levels when implementing similar regeneration strategies across different regions [49][58][49,58]. The issue of brownfields is perceived by residents in relation to the conditions of their city [63]. This highlights the need to study public opinions across various regions. Table 1 presents an overview of previous empirical studies conducted on brownfield regeneration and public opinion. The table outlines the key findings and methodologies employed in each study.3. Brownfield Regeneration and Heritage Preservation

Brownfield physical structures, whether historical or non-historical, can be preserved for reuse as a symbol of the site’s past identity [36]. In addition to physical preservation, the building’s authenticity should be preserved by assigning suitable functions [64]. In other words, intangible aspects such as social activities, collective memories, and meanings should be considered alongside tangible heritage [24][34][24,34] to define the site’s unique identity and strengthen the sense of belonging [65]. Given that these sites and buildings have been integral to cities and served as workspaces for decades, the locals have developed a strong emotional attachment to these places due to their daily interaction with them. This bond can be utilized during site regeneration to enhance local identity [66][67][66,67]. Additionally, creating an accessible and open environment can revive a community’s emotional connection to historical sites and expose them to visitors and innovative uses [68][69][68,69]. Thus, although the sites’ primary function is no longer present, the adaptive reuse project aims to maintain their unique historical and cultural identity [70], preserving genius loci [39] while accommodating contemporary needs [71]. Preserving historical structures in brownfield regeneration facilitates tourism’s economic impact and supports sustainable urban development [28]. Tourism motivates heritage preservation [34]. Historical brownfields with architectural and urban significance can be transformed into tourist attractions and increase the possibility of their preservation [72]. Brownfields in city centers have the potential for integration into urban life, and their reuse for tourism and recreation can support urban development [73]. These tourist attractions can help to reconstruct the economy, revive industrial history, and enhance local identity [31][32][31,32]. However, tourism development may lead to disregard of society’s cultural and intangible heritage value for commercial purposes [34][74][34,74]. Heritage interpretation maintains authentic place identity and provides a meaningful heritage experience for visitors and local stakeholders [24][34][75][24,34,75], positively impacting their behavior and connection to the site [76]. Therefore, preserving the authenticity of heritage buildings is crucial to strengthen the sense of identity, connect past with present and future, and consolidate collective memory [77]. Nevertheless, the brownfield regeneration process faces several limiting barriers. Economic factors are the primary obstacle, followed by legislative, procedural–administrative, and political hurdles [78]. Economic factors are the main barriers in the United States [79], Canada [80], and Pakistan [81]. Mehdipour [35] highlights the economic implications of land development and marketing on future brownfield policies in Iran. Preserving brownfields for industrial heritage may be the preferred social choice [72]. However, demolition and landscaping to create green spaces [10], or economically driven new development after demolition [82] are alternative options. The destiny of brownfields should be determined through negotiations involving investors, local government officials, and stakeholder representatives. Notably, brownfields of significant historical importance offer distinct regeneration prospects [27].Table 1.

Summary of previous empirical research on brownfield regeneration and public opinion.

| Study No. | Authors | Year | Location | Data Collection Method | Variable/Criteria/Index | Data Analysis Method | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | K’oyoo et al. [83] | 2022 | Kenya | Questionnaire survey; interview with key informants. |

Public perception of effects of the post-mine brownfields on the environment; public perception on dumping of waste; public perception on air pollution; public perception on possible contamination. |

Descriptive statistics including percentages; qualitative data analysis (thematic analysis). |

Brownfields experienced waterlogging and illegal dumping, causing health risks in adjacent residential areas. Each brownfield possesses distinctive spatial features that have led to negative impacts on the neighboring environment. |

| 2 | Martinat et al. [57] | 2018 | Czech Rep. | Questionnaire survey. | Satisfaction with the aesthetic and functional state of present regeneration; possibilities for the reuse of present brownfield. |

Nonparametric Wilcoxon and Friedman test; multivariate statistical techniques including PCA, RDA. |

The predominant choices for reuse were culture/sport and children’s park. Gender significantly predicted reuse options. |

| 3 | Mathey et al. [84] | 2018 | Germany | Questionnaire survey; photomontages. |

Perception of urban brownfields; use of brownfields; preferred uses and design of urban brownfields. |

Descriptive statistics; cross-correlations. |

Locals possess specific opinions on brownfield utilization or development, with a desire to participate in the transformation process. |

| 4 | Navratil et al. [27] | 2018 | Czech Rep. | Questionnaire survey. | The perception of the given regenerated brownfield; general perceptions of brownfield regenerations; regenerated brownfields as a tourism “destination”; satisfaction with heritage preservation. |

Nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis and Friedman test; multivariate statistical techniques including RDA. |

The awareness of brownfield regeneration is low. The conditions and technical status of brownfields significantly influence respondents’ views on regeneration choices. The visitors’ response to the leisure time reuse of brownfields is favorable. Concern for cultural heritage in society can accelerate regeneration. |

| 5 | Navratil et al. [55] | 2018 | Czech Rep. | Questionnaire survey | Reuse of brownfields; brownfields location within city; spatial factors influencing attitudes of residents towards brownfields. Regeneration; involvement with brownfield regeneration. |

Two-factorial ANOVA. | Citizens’ perceptions of brownfield regeneration options depend on (1) the extent of brownfields in a city, (2) brownfield location within a city’s borders, (3) place of residence, and (4) type of regeneration. |

| 6 | Kim and Miller. [59] | 2017 | Virginia, the United States | Questionnaire survey; visual preference survey (VPS). |

Six landscape-based types to classify brownfields; the effect of preconception; the effect of health concern. |

Descriptive statistics including mean rating and frequency analysis, analysis of variance (MANOVA and ANOVA). |

Preserved historical buildings and landscapes were prioritized for redevelopment, while sites containing industrial remnants received lower priority. Respondents associated these types with harmful pollutants that may affect human health. |

| 7 | Loures et al. [13] | 2016 | Portugal | Questionnaire survey. | The importance of planning and design dimensions to landscape transformation; the actual condition of the municipal landscape; main responsibility for post-industrial land transformation; uses/functions that should be implemented in the redevelopment. |

Descriptive statistics. | Brownfield regeneration projects are well received by the community. The most popular options are multifunctional and leisure green spaces. |

| 8 | Martinat et al. [6] | 2016 | Czech Rep. | Questionnaire survey. | Options for reusing post-mining brownfields; the urgency of regeneration of local brownfields; financial sources for brownfield regeneration projects. |

Descriptive statistics. | Public awareness of brownfields is limited. Brownfields in remote areas offer chances for new industries to create jobs in a city struggling with unemployment. |

| 9 | Rink and Arndt [85] | 2016 | Germany | Questionnaire survey; photomontages. |

Perception of successional brownfields; perception of afforestation sites; perception of threats (natural, social and contamination); perception of usability. |

Descriptive statistics. | Residents viewed park-related green structures and traditionally designed urban nature areas positively. Afforestation on brownfields was more accepted than natural succession. Afforestation was considered less threatening than successional scenarios. The usability of forestry scenarios was markedly superior to that of succession scenarios. |

| 10 | Kunc et al. [86] | 2014 | Czech Rep. | Questionnaire survey. | Awareness, urgency and rate of apprehension of pollution about brownfields; evaluation of brownfield regeneration policy in two cities; the most problematic locality and best practice for the regeneration project of two cities; future utilization. |

Descriptive statistics including percentages. | The term “brownfield” was not widely known. The most popular options for reuse were housing and greenery. An open and responsive urban policy is crucial for brownfield regeneration, increasing local satisfaction. |

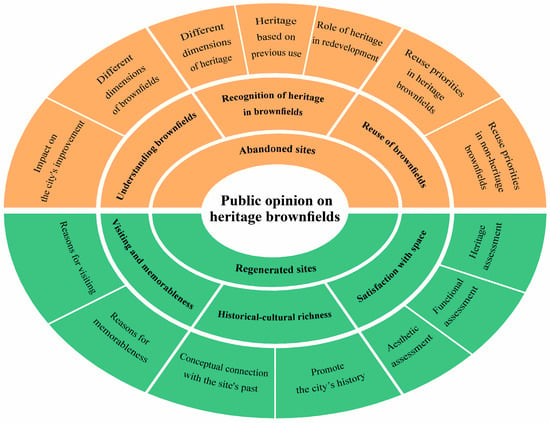

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of public opinion on heritage brownfields.