Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Ioannis Passas.

Empirical research identifies whistleblowing as one of the most effective internal antifraud controls. Very recently, Directive 1937/2019 became effective in the EU, aiming to deal with the defragmentation of whistleblowing legislation among the member states and provide common minimum accepted standards.

- whistleblowing

- EU Directive 1937

- benchmarking

1. Introduction

The most recent (ACFE 2022) study identifies whistleblowing as the most effective fraud identification method with a great difference from the second one, while the recent adoption of the (Directive (EU) 2019/1937) in the EU draws the attention of organizations and anti-fraud professionals (fraud examiners and internal auditors).

The first maturity models were developed in the 1990s in management and information technology to assess the level of competency, capability, or sophistication of business processes (De Bruin et al. 2005). Although it is not a requirement for a maturity model to be validated to be helpful, validation by experts may provide valuable inputs, insights, and a degree of assurance in respect to its credibility and relevance. In practice, many maturity models have been validated through the Delphi method (for example CR3M developed by (Głuszek 2021) and the BPAMM developed by (Martinek-Jaguszewska and Rogowski 2022), while others are not (KPMG 2013; ACFE and Grant Thornton 2020).

The Delphi method was developed in the 1950s by the Rand Corporation (Turoff and Linstone 2002), and since then it has been used in various sectors, including public health, transport, and education (Kittell-Limerick 2005). The Delphi Method aims to «obtain the most reliable consensus of a group of experts by a series of intensive questionnaires interspersed with controlled feedback» (Turoff and Linstone 2002). The use of this method is appropriate where the subject matter is complex (Ono and Wedemeyer 1994), where empirical evidence is lacking (Murphy et al. 1998), or when the knowledge is incomplete (Turoff and Hiltz 1996). That is applied to whistleblowing because it is a complex phenomenon that depends on legal, organizational, situational, and personal factors. In addition, although there is extensive research on the factors facilitating or discouraging whistleblowing, the study of whistleblowing as a control mechanism is limited.

2. Whistleblowing

Before developing the maturity model, it is necessary to understand the nature of whistleblowing, its limitations, its place in the internal control framework, and the need for a whistleblowing maturity model. One of the major limitations in the academic research of whistleblowing is that there is no commonly accepted definition. Near and Miceli (1985) defined whistleblowing as «the disclosure by organizational members (former or current) of illegal, immoral, or illegitimate practices under the control of their employers, to persons or organizations that may be able to effect action», while (Ravishankar 2003) defined whistle-blowers as the «employees who bring wrongdoing at their organizations to the attention of superiors». These definitions indicate the need for specific results. That differentiates whistleblowing from rumors, gossip, or grievances. However, other researchers suggested that considering only employees as whistleblowers may no longer be appropriate and may not adequately portray the whistleblower (Ayers and Kaplan 2005). Empirical evidence (ACFE 2022) shows that reports can also derive from external parties, in rare cases, even from competitors verifying this perspective. In addition, reports from external parties provide «greater evidence of wrongdoing, and they tend to be more effective in changing organizational practices» (Dworkin and Baucus 1998). Other definitions concentrated on whistle-blowers and their virtues rather than on the act of whistleblowing itself (for example (Berry 2004) and (Alford 2002)), hypothesizing that whistleblowers are highly ethical individuals with the courage to face the fear of reprisal. However, other studies have shown that in many cases, whistleblowers act opportunistically (Henik 2015). A more appropriate definition has been provided by (TI-NL 2019) that defined whistleblowing as «the disclosure of information related to corrupt, illegal, fraudulent or hazardous activities being committed in or by public or private sector organizations—which are of concern to or threaten the public interest—to individuals or entities believed to be able to effect action». Internal controls can be distinguished based on two criteria. The first is whether the internal control is designed to prevent the occurrence of loss events (preventive control) or to identify internal control failures (detective control) after their occurrence. Whistleblowing has been categorized as a «potentially active or passive detection method» by (ACFE 2022) and as «an essential last line of defense in companies’ systems of internal control» (ICAEW 2019), meaning that it is more a detective rather than a preventive one. The second criterion is whether the internal control is specific to certain transactions or business processes (specific control) affects the control environment as a whole (entity-level control). Whistleblowing is an entity-level control with a pervasive effect in the control environment. Even though whistleblowing is effective internal control, it is also associated with many limitations. Inertia may be one of the most significant ones. Organizations often received early notice but failed to act upon them. The example of Harry Markopolos may be one of the most indicative examples. Harry Markopolos, a financial analyst and fraud examiner, provided red flags of fraud to SEC for the biggest Ponzi scheme in history for over a decade before it imploded. However, his concerns were ignored repeatedly and when the fraud was exposed, the losses for the investors had already reached 65bn US dollars (The Guardian 2010). However, inertia may also derive from those who observe wrongdoing or business risks. Following (Miceli et al. 1987), whistleblowing is a «complex phenomenon that is based upon organizational, situational, and personal factors» which is not entirely within the control of the organizations, and «it is virtually impossible to change individuals’ core values which have been learned and consolidated over a lifetime» (ICAEW 2019). Academic literature and empirical evidence reveal that frequently too little information comes to the attention of the management or the regulators, and if it does come, it may come too late. For example, the Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards was shocked by the evidence that so many people ignored misbehavior (CIIA 2014). As a result, the main weakness of whistleblowing as an internal control is that it depends on human behavior.3. Maturity Models

Maturity models are often used on a self-assessment basis to help organizations understand their current level of capability in a particularly functional, strategic, or organizational area (OECD 2022). Maturity models provide a holistic approach (Martinek-Jaguszewska and Rogowski 2022) to depict the current situation based on objective criteria; envision the future, and find a way to achieve the desired state by following a disciplined method that is easy to use and implement (IIA 2013). In addition, the maturity models provide an early warning for an organization’s challenges (OECD 2022). Effectively, maturity models contribute to achieving a business process’s full potential. For these reasons, maturity models have been used in many areas, including information systems development (OECD 2022), internal auditing (KPMG 2013; OECD 2021; IIA 2019), fraud prevention and deterrence (ACFE and Grant Thornton 2020), tax law enforcement (OECD 2019a, 2019b, 2020). The fact that the Institute of Internal Auditors issued a practice guidance specifically in selecting, using, and developing maturity models before a decade proves their relevance to the internal audit. In addition, the (ACFE 2022) study reveals that the primary internal control failures that contributed to fraud are the lack of internal controls (29%); override of controls (20%); poor tone at the top (10%); lack of competent personnel in oversight roles (8%). A robust whistleblowing framework may reduce all these internal control failures. For example, management may be reluctant to override controls when the possibility of getting caught is high; additional internal controls may be implemented or the existing ones need to be improved.4. Whistleblowing Maturity Framework

4.1. Development of Maturity Models

Usually, the maturity models are ranked using five steps. Each step illustrates the current or desired capabilities (De Bruin et al. 2005) and follows a reasonable escalation or path from the lowest to the highest. The maturity models can be distinguished to:-

Descriptives that are useful to depict the current situation;

-

Prescriptive maturity models that also provide a roadmap to achieve the desired outcomes and;

-

Comparative maturity models that also allow internal or external benchmarking (Becker et al. 2009).

-

To determine the model and its components;

-

To determine its scale and;

-

To determine the expectations for each component.

4.2. Stages

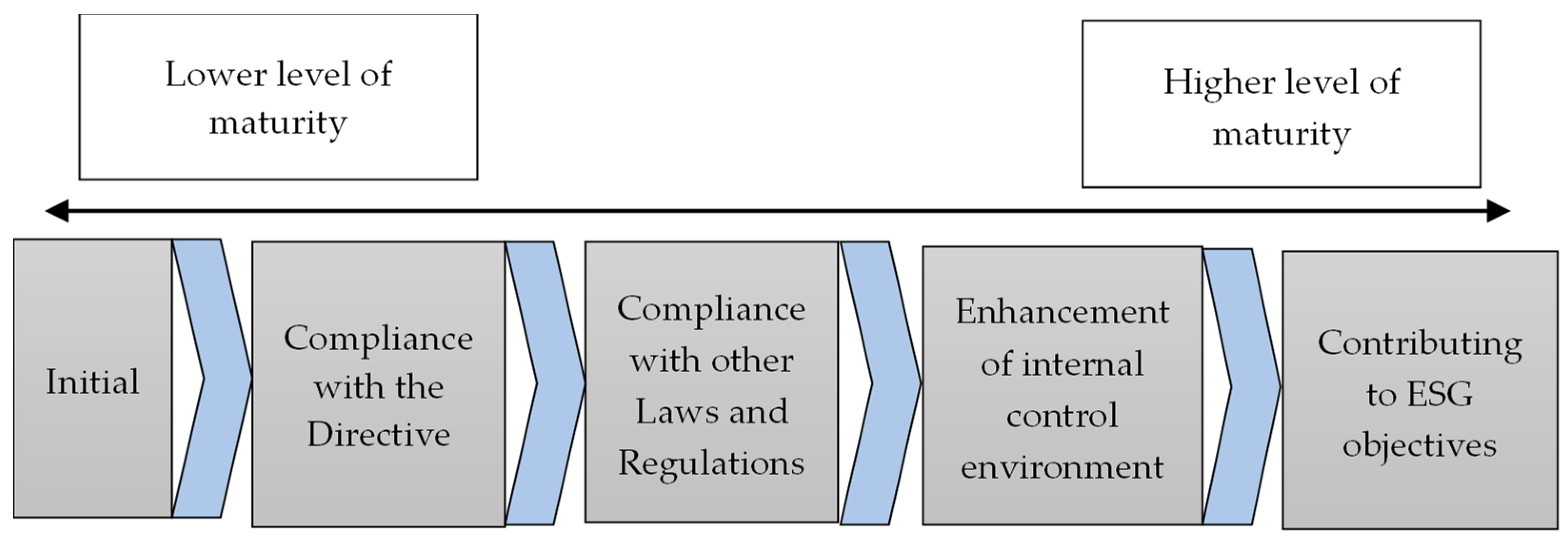

The first stage initially considered is compliance with the (Directive (EU) 2019/1937). The underlying logic is that non-compliance is not an option. Many organizations will consider this stage sufficient. However, it is likely that many organizations will use whistleblowing to comply with other laws and regulations not included in the scope of the Directive or their code of conduct. The «wheel of whistleblowing» suggested by (Culiberg and Mihelič 2017) includes many wrongdoings and threats not included in the scope of the (Directive (EU) 2019/1937). In addition, other organizations may also use whistleblowing to enhance their risk management or to achieve their ESG objectives. In accordance with (ICAEW 2019) whistleblowing provides a weapon to root out complacency and inertia which can be viewed as rigorousness for enhancing the internal control environment. In respect of the contribution of whistleblowing to achieve ESG objectives the (Directive (EU) 2019/1937) includes many wrongdoings that affect society while the «wheel of whistleblowing» suggests even more (Culiberg and Mihelič 2017). Therefore, the maturity levels (see as Figure 1) of the suggested WBMM are:

Figure 1. Designed by the authors.

-

Initial;

-

Compliance with the Directive;

-

Compliance with other laws and regulations;

-

Enhancement of internal control environment and;

-

Contributing to the achievement of ESG objectives.

4.3. Components

The components identified through a thorough study of the literature are divided into eight categories:-

The scope of the whistleblowing policy;

-

Corporate governance;

-

Reporting mechanisms;

-

Protection;

-

Tone at the top;

-

Organizational culture and human resource practices;

-

Objective investigations and;

-

Monitor and review.

4.3.1. Scope

The scope of whistleblowing is two-dimensional and comprises what wrongdoings or dangers will be reported and followed up on and who can report them. The first dimension has already been analyzed. Regarding the second, the (Directive (EU) 2019/1937) also determines the persons who have the right to report. However, in some cases, organizations may be appropriate to expand the possible reporting persons.4.3.2. Corporate Governance

Corporate governance refers to the mechanisms that provide the basis for objective investigations and corporate reporting. This component is divided into three elements:-

Overall responsibility;

-

Assurance and;

-

Corporate reporting.

4.3.3. Reporting Mechanisms

Reporting mechanisms include all necessary steps to enable a possible reporting person to make informed decisions on whether and how to report and provide secure reporting channels. The elements considered are:-

Anonymity;

-

Reporting channels;

-

Advice on reporting and;

-

Visibility, clarity, and completeness of the information.

4.3.4. Protection

Academic research, empirical evidence, and the (Directive (EU) 2019/1937) identified the threat of retaliation as a primary factor negatively affecting the decision to report. The consequences to the whistle-blower may vary significantly in terms of severity, from negative perceptions against whistle-blowers (Worth 2013), negative consequences in the work environment such as bullying (Bjørkelo 2013), to blackballing isolation, humiliation (Berry 2004), to psychological effects such as depression (Bechtoldt and Schmitt 2010), anxiety (Bjørkelo 2013), post-traumatic stress (Kreiner et al. 2008) or even to become life-threatening. Protection covers the confidentiality of the reporting person’s identity and any person referred to the reports as required by the (Directive (EU) 2019/1937) and the provision of adequate anti-retaliation measures. A practical implication may arise in cases where the organization has operations in jurisdictions will less robust legal protection. In such a case, it shall determine whether the same protection will be granted voluntarily.4.3.5. Tone at the Top

The (ACFE 2022) identifies the lack of proper tone at the top as an internal control weakness in many frauds. The relationship between whistleblowing and tone at the top is bilateral, employees will only report if they know the whistleblowing policy and they believe that the top management supports it (Tsahuridu and Vandekerckhove 2008). On the other hand, if top the management is negligent in receiving and investigating reports, the wrongdoing could be seen as a routine practice (Kaptein 2011).4.3.6. Organizational Culture and Human Resource Practices

For the purposes of this restudyearch, organizational culture initially distinguished to:-

Risk culture;

-

Ethical culture;

4.3.7. Investigations

The investigation of reports is the ultimate purpose of the whole whistleblowing mechanism. The elements initially considered that will allow unbiased judgments are:-

Organizational independence of the investigation team;

- Learning culture and;

-

Professional training;Cultural differences.

-

Appropriate risk prioritization;

-

Investigation protocols and;

-

Contribution to risk management.

References

- ACFE (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners). 2022. Occupational Fraud 2022. A Report to the Nations. Available online: https://legacy.acfe.com/report-to-the-nations/2022/ (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Directive (EU). 2019. Directive (EU) 2019/1937 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2019 on the Protection of Persons Who Report Breaches of Union Law. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32019L1937 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- De Bruin, Tonia, Michael Rosemann, Ronald Freeze, and Uday Kaulkarni. 2005. Understanding the main phases of developing a maturity assessment model. In Australasian Conference on Information Systems (ACIS). Brisdane: Brisdane Australasian Chapter of the Association for Information Systems, pp. 8–19.

- Głuszek, Ewa. 2021. Use of the e-Delphi method to validate the corporate reputation management maturity model (CR3M). Sustainability 13: 12019.

- Martinek-Jaguszewska, Klaudia, and Waldemar Rogowski. 2022. Development and Validation of the Business Process Automation Maturity Model: Results of the Delphi Study. Information Systems Management 2022: 1–17.

- KPMG. 2013. Transforming Internal Audit: A Maturity Model from Data Analytics to Continuous Assurance. Available online: https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2015/09/ch-pub-20150922-transforming-internal-audit-maturity-model-en.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- ACFE (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners), and Grant Thornton. 2020. Anti-Fraud Playbook. Available online: https://www.grantthornton.com.tr/globalassets/1.-member-firms/turkey/rapor-ve-aratrmalar/antifraud-playbook.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Turoff, Murray, and Harold A. Linstone. 2002. The Delphi Method-Techniques and Applications. Boston: Addison Wesley Publishing Company.

- Kittell-Limerick, Patricia. 2005. Perceived Barriers to Completion of the Academic Doctorate: A Delphi Study. Commerce: Texas A&M University-Commerce.

- Ono, Ryota, and Dan J. Wedemeyer. 1994. Assessing the validity of the Delphi technique. Futures 26: 289–304.

- Murphy, M. K., N. A. Black, D. L. Lamping, C. M. McKee, C. F. Sanderson, J. Askham, and T. Marteau. 1998. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technology Assessment 2: i-88.

- Turoff, Murray, and Starr Roxanne Hiltz. 1996. Computer based Delphi processes. In Gazing into the Oracle: The Delphi Method and Its Application to Social Policy and Public Health. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 56–85.

- Near, Janet P., and Marcia P. Miceli. 1985. Organizational dissidence: The case of whistle-blowing. Journal of Business Ethics 4: 1–16.

- Ravishankar, Lilanthi. 2003. Encouraging Internal Whistleblowing in Organizations. Available online: https://www.scu.edu/ethics/publications/submitted/whistleblowing.html (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Ayers, Susan, and Steven E. Kaplan. 2005. Wrongdoing by consultants: An examination of employees’ reporting intentions. Journal of Business Ethics 57: 121–37.

- Dworkin, Terry Morehead, and Melissa S. Baucus. 1998. Internal vs. external whistleblowers: A comparison of whistleblowering processes. Journal of Business Ethics 17: 1281–98.

- Berry, Benisa. 2004. Organizational culture: A framework and strategies for facilitating employee whistleblowing. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 16: 1–11.

- Alford, C. F. 2002. Whistleblowers: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. Austin: Cornell University Press.

- Henik, Erika. 2015. Understanding whistle-blowing: A set-theoretic approach. Journal of Business Research 68: 442–50.

- TI-NL (Transparency International Netherland). 2019. Whistleblowing Frameworks 2019. In Assessing Companies in Trade, Industry, Finance, and Energy in the Netherlands. Amsterdam: Transparency International Netherland.

- ICAEW (Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales). 2019. How Whistleblowing Helps Companies. Available online: https://www.icaew.com/technical/corporate-governance/committees/corporate-culture/culture-articles/how-whistleblowing-helps-companies#:~:text=Whistleblowing%20is%20central%20to%20a,ICAEW%20chief%20executive%20Michael%20Izza (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- The Guardian. 2010. The Man Who Blew the Whistle on Bernard Madoff. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2010/mar/24/bernard-madoff-whistleblower-harry-markopolos (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Miceli, Marcia P., Janelle B. Dozier, and Janet P. Near. 1987. Personal and Situational Determinants of Whistleblowing. Paper presented at the Meeting of the Academy of Management, New Orleans, LA, USA, November 1.

- CIIA (Chartered Institute of Internal Auditors). 2014. Whistleblowing and Corporate Governance. In The Role of Internal Audit in Whistleblowing. London: Chartered Institute of Internal Auditors.

- OECD. 2022. Tax Administration Maturity Model Series Analytics Maturity Model. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/publications-and-products/analytics-maturity-model.htm (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- IIA (The Institute of Internal Auditors). 2013. Selecting, using, and creating maturity models. In A Tool for Assurance and Consulting Engagements. Lake Mary: The Institute of Internal Auditors.

- OECD. 2021. Enterprise Risk Management Maturity Model. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/publications-and-products/enterprise-risk-management-maturity-model.htm (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- IIA (The Institute of Internal Auditors). 2019. Internal Audit Capability Model (IA-CM) For the Public Sector. Lake Mary: The IIA Research Foundation.

- OECD. 2019a. Tax Compliance Burden Maturity Model. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/publications-and-products/tax-compliance-burden-maturity-model.htm (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- OECD. 2019b. Tax Debt Management Maturity Model. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/publications-and-products/tax-debt-management-maturity-model.htm (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- OECD. 2020. Tax Crime Investigation Maturity Model. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/tax/crime/tax-crime-investigation-maturity-model.htm (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Becker, Jörg, Ralf Knackstedt, and Jens Pöppelbuß. 2009. Developing maturity models for IT management: A procedure model and its application. Business & Information Systems Engineering 1: 213–22.

- Culiberg, Barbara, and Katarina Katja Mihelič. 2017. The evolution of whistleblowing studies: A critical review and research agenda. Journal of Business Ethics 146: 787–803.

- PCBS (Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards). 2013. Available online: https://www.parliament.uk/globalassets/documents/banking-commission/Banking-final-report-volume-i.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- PCW (Public Concern at Work). 2013. Report on the Effectiveness of Existing Arrangements for Workplace Whistleblowing in the UK. London: Public Concern at Work.

- Greene, Annette D., and Jean Kantambu Latting. 2004. Whistle-blowing as a form of advocacy: Guidelines for the practitioner and organization. Social Work 49: 219–30.

- GRI (Global Reporting Initiative). 2018. GRI 102: General Disclosures 2016. Amsterdam: Global Reporting Initiative.

- Hersh, Marion A. 2002. Whistleblowers—Heroes or traitors?: Individual and collective responsibility for ethical behaviour. Annual Reviews in Control 26: 243–62.

- Worth, Mark. 2013. Whistleblowing in Europe: Legal protections for whistleblowers in the EU. Transparency International Secretariat 2013: 91–111.

- Bjørkelo, Brita. 2013. Workplace bullying after whistleblowing: Future research and implications. Journal of Managerial Psychology 28: 306–23.

- Bechtoldt, Myriam N., and Kathrin D. Schmitt. 2010. It’s not my fault, it’s theirs: Explanatory style of bullying targets with unipolar depression and its susceptibility to short-term therapeutical modification. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 83: 395–417.

- Kreiner, Barbara, Christoph Sulyok, and Hans-Bernd Rothenhäusler. 2008. Does mobbing cause posttraumatic stress disorder? Impact of coping and personality. Neuropsychiatrie: Klinik, Diagnostik, Therapie und Rehabilitation: Organ der Gesellschaft Osterreichischer Nervenarzte und Psychiater 22: 112–23.

- Tsahuridu, Eva E., and Wim Vandekerckhove. 2008. Organisational whistleblowing policies: Making employees responsible or liable? Journal of Business Ethics 82: 107–18.

- Kaptein, Muel. 2011. From inaction to external whistleblowing: The influence of the ethical culture of organizations on employee responses to observed wrongdoing. Journal of Business Ethics 98: 513–30.

- IIAA (The Institute of Internal Auditors Australia). 2021. Auditing Risk Culture: Practical Guide. Available online: https://www.iia.org.au/sf_docs/default-source/technical-resources/iia_auditing-risk-culture-guide-fa.pdf?sfvrsn=4 (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Miceli, Marcia P., Janet P. Near, and Charles R. Schwenk. 1991. Who blows the whistle and why? ILR Review 45: 113–30.

- Painter-Morland, Mollie. 2010. Questioning corporate codes of ethics. Business Ethics: A European Review 19: 265–79.

- Schmidt, Chris. 2020. Why risk management frameworks fail to prevent wrongdoing. The Learning Organization 27: 133–45.

- Tavakoli, A. Assad, John P. Keenan, and Biljana Cranjak-Karanovic. 2003. Culture and whistleblowing an empirical study of Croatian and United States managers utilizing Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. Journal of Business Ethics 43: 49–64.

- Zhuang, Jinyun, Stuart Thomas, and Diane L. Miller. 2005. Examining culture’s effect on whistle-blowing and peer reporting. Business & Society 44: 462–86.

More