Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Alfred Zheng and Version 1 by Zhengchun Liu.

Considering the increasing concern for food safety, electrochemical methods for detecting specific ingredients in the food are currently the most efficient method due to their low cost, fast response signal, high sensitivity, and ease of use.

- three-dimensional (3D) electrodes

- food safety

- components detection

- Glucose Detection

- Food Additives

- Food Preservatives

1. Introduction

As society develops and people’s living standards rise, more and more food types are consumed as a daily diet [1,2][1][2]. In the meantime, foodborne infections are becoming a more significant threat to public health because of improper food handling and storage [3]. Therefore, it is crucial for practical reasons that pathogenic elements in food are quickly and sensitively detected, as well as hazardous compounds [4]. A variety of methods have been applied in the field of food detection, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [5], spectroscopy [6], spectrophotometry [7], capillary electrophoresis [8], etc. And the traditional methods for detecting foodborne pathogens are viable cell counting [9], plate separation [10], enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [11], etc. However, these technologies have been limited in their applicability due to adverse elements, including expensive detection costs, sluggish response times, convoluted pre-processing and operation processes and poor detection accuracy [12]. Furthermore, especially in real samples, the detection results are often unsatisfactory under the influence of multiple similar interferents. Thus, a huge demand exists for detecting platforms with high sensitivity, high repeatability, and interference immunity. Electrochemical sensors are the most desirable detecting instruments because of their dependability, low detection limits, the outstanding response signal, and cheap assembly cost [13,14][13][14]. Furthermore, electrochemical sensors can detect and analyze the composition and content of substances to be measured by recording the changing electrical signal generated by the redox reactions between the electrode materials and the target materials. Therefore, electrochemical sensors can be easily utilized in food safety, medical testing, and water quality monitoring by simply synthesizing electrode materials that can undergo specific reactions with target materials [15,16][15][16]. The outcomes of electrochemical sensor detection are primarily represented by current, potential, and resistance changes depending on the various electrochemical signals [17,18][17][18]. And because electrochemical sensing is the most popular method of monitoring electric currents, this research concentrates on it. For current indications, voltammetry and amperometry are the most common detection methods. Voltammetry comprises many forms, such as cyclic voltammetry (CV), differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), linear scanning voltammetry (LSV), etc. [19]. Amperometry differs from voltammetry in that it does not use a scanning potential during the detection process; instead, the change in current and time is recorded. Based on this, three-electrode electrochemical sensors can achieve detection not only in an electrolytic cell but also in real-time by creating tiny flexible electrodes or microfluidic devices [20]. So, constructing portable food detection equipment based on electrochemical sensing is promising. With their distinctive physicochemical and surface charge characteristics, nanomaterials have recently made significant advancements in engineering and manufacturing [21,22][21][22]. In particular, nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors are widely used to detect food safety [23]. Furthermore, compared to macroscopic materials, the larger surface area of nanostructured electrodes led to more significant electrocatalytic activity and detection response, achieving lower detection limits and faster response times [24]. Among them, three-dimensional (3D) nanomaterials outperform other materials like 0, 1 and 2-dimensional in adsorption capacity, mass transfer capacity, and site exposure capacity [25]. Therefore, 3D electrodes constructed from 3D nanomaterials are more likely to produce redox reactions with the measured ingredients. In addition, 3D electrodes can combine the advantages of one- and two-dimensional structures and even demonstrate electrochemical performance superior to their components [26,27][26][27]. At present, electrochemical sensors assembled by 3D electrodes are mainly divided into two categories, one is to build 3D arrays on the electrode surface, and the other is to modify the electrodes by using 3D structured nanomaterials [28,29,30,31][28][29][30][31]. The most common types of 3D nanomaterials are carbon materials and their derivatives, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), metal oxides/hydroxides, alloys, and various composite materials [32,33][32][33]. However, 3D materials have several problems restricting their use in electrochemical sensing. The biggest concern is the electrode’s poor overall conductivity and propensity to aggregate when each structural unit is independent. Consequently, by means of metal particle doping, surface modification, and hole-making treatment, the electrical conductivity is considerably increased while keeping the original structure. Moreover, including 1D carbon nanotubes (CNTs), Ag nanowires, etc., can provide the same result [34]. Therefore, appropriate regulation of 3D electrode materials can improve electrochemical sensor detection accuracy, increase electron mobility, and fully exploit the benefits of 3D electrodes.2. Applications of 3D Sensors for Glucose Detection

The increasing incidence of diabetes has caused widespread concern among researchers year after year. The primary cause of this problem is overusing glucose in the diet. Electrochemical sensing techniques differ from colorimetric, optical approaches and SERC (surface-enhanced Raman scattering) because they are less expensive, more sensitive, and easier to build detection platforms. By using the catalytic oxidation of glucose, a class of non-enzymatic electrochemical sensors in electrochemical sensing avoid the loss of glucose oxidase activity brought on by the presence of oxygen in the environment, which would reduce detection sensitivity. Numerous 3D structured nanomaterials have been utilized as electrode materials for enzyme-free sensors because of their distinct formative benefits. Here, Wang et al. decorated two-dimensional MoS2 on CuCo2O4 using a hydrothermal technique to produce three-dimensional nanoflowers-like heterogeneous structures successfully employed to detect glucose in real-time [132][35]. The resulting MoS2@CuCo2O4 electrode materials exhibit superior sensing properties, mainly due to the 3D structure supported by MoS2 that prevents the stacking of nanosheets.3. Applications of 3D Sensors for Detections of Bioactive Food Components

The modern food industry must find green and healthy foods because the number of people who are currently unwell is rising owing to the irrational diet structures of contemporary people. The amount of beneficial ingredients in healthy food is an essential indicator of assessing food quality, so a safe and low-cost testing method is needed. Compared with other methods, electrochemical testing has the advantages of environmental protection, simple operation and high efficiency. For instance, Thenrajan et al. synthesized CoNiFe-ZIF microfibers via electrostatic spinning to detect green tea catechins (CTs) with antioxidant characteristics and increased physiological activity [135][36]. Compared to bare GCE, 3D porous microfibers loaded with NiCoFe-ZIF can be fully bound with CTs and have better sensing performance. The detection limits for the simultaneous detection of the three CT groups (epigallocatechin-3-gallate, epicatechin and epicatechingallate) corresponded to 45 ng, 8 ng and 4 ng, respectively. The linear detection range was 50 ng–1 mg. The antiviral and anti-inflammatory characteristics of luteolin (3′,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone), which are found in vegetables, have also caught the interest of experts. Tang et al. created an Ag-modified bimetallic CoNi-MOF at a temperature close to room temperature [136][37]. Ag-loaded flower-like microsphere structure can not only better promote the diffusion of electrolyte ions but also enhance the catalytic activity of luteolin. The Ag-CoNi-MOF-based sensors had a linear detection range of 0.002 to 1.0 μM and a detection limit of 0.4 nM.4. Applications of 3D Sensors for Detections of Food Additives

Smart use of food additives can increase consumer appetite but using them in excess is dangerous. As a result, Balram et al. synthesized a Ni-Co3O4 NPs/GO showing excellent response to the sulfonated azo dye Sunset Yellow (SY) in an electrochemical sensing platform [137][38]. Among them, the 3D structure of Co3O4 as ap-type semiconductor oxides with dual direct band gaps provides a clear and tunable structure. The addition of Ni nanoparticles to the Co3O4 lattice enhances conductivity. Finally, the hybridization with carbon-based materials significantly enhances the nanocomposite’s electrocatalytic abilities and electroactive surface area. Thanks to the synergistic effect, the linear range of the yellow sunset sensor was 0.125–108.5 μM, the detection limit was 0.9 nM, the sensitivity was 4.16 μA μM−1 cm−2, and the recovery rate was 96.16–102.56% in the actual detection of SY in various beverages and foods. In another research, Garkani Nejad et al. prepared MnO2 nanorods anchored graphene oxide (MnO2 NRs/GO) composites by hydrothermal method. As observed by FE-SEM, MnO2 NRs/GO displayed sheet-shaped and rod-like 3D mixed morphology [138][39]. The same structural benefits also allow composites to perform well in detecting SY. A detection limit of 0.008 μM was obtained, with a linear detection range of 0.01–115.0 μM. In addition, to Go, carbon materials with various morphologies and excellent electrical conductivity can be employed to detect SY sensitively. Using a one-step hydrothermal technique, Chen et al. synthesized hollow carbon spheres (HCS) and NiS composite-modified GCE for SY measurement [139][40]. The ability to transport electrons and detect SY is considerably enhanced by the synergistic action of NiS and HCS. The linear detection range of SY is 0.01–100 μM, and the detection limit is 0.003 μM. Joseph et al. combined WC with irregularly spherical FeMn-LDH to create composite materials with novel layered structures and successfully detected the antioxidant diphenylamine (DPA), which can protect food from spoilage during storage [140][41]. Due to the two materials’ deep hybridization and synergy, electrochemical sensors exhibited a wide linear range (0.01–183.34 μM) and a low detection limit (1.1 nM) that have been electrochemically confirmed. Ghalkhani et al. prepared a 3D hybrid structure of CoFe2O4@SiO2@HKUST-1 by self-assembly technique [141][42]. Under ideal circumstances, CoFe2O4@SiO2@HKUST-1 can significantly increase the oxidation of azaperone (AZN), frequently employed in animal husbandry as a muscle relaxant to improve meat quality. The electrochemical evaluation showed that AZN could be adsorbed and enriched on the surface of the CoFe2O4@SiO2@HKUST-1 modified electrode, and satisfactory detection results were obtained in the linear range of 0.05–10,000 nM with a detection limit of 0.01 nM. Since carbon material has good mechanical and conductivity capabilities, using 1D and 2D carbon materials in sensible designs is a smart way to increase the sensor’s performance. Xia et al. found that a molecularly imprinted proportional sensor constructed from a composite of carbon nanotubes, Cu2O NPs and Ti3C2Tx could achieve sensitive detection of the growth-promoting hormone diethylstilbestrol (DES) [142][43]. The accordion structure of Ti3C2Tx can adsorb large amounts of loaded Cu2O NPs by electrostatic force, while CNT can improve the sensor’s sensitivity. The electrochemical sensors can detect DES in a wide concentration range of 0.01 to 70 μM, with good linearity and a very low detection limit (6 nM). Similar work was the functionalization of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) using metal particles by Keerthi et al. [143][44]. Strong interactions caused the spherically positively charged Ti particles to grow on tubular MWCNTs. This typical tubular shape was interconnected and exhibited remarkable electrocatalytic effects on the Ractopamine (RAC) animal feed additive, which was widely utilized in the livestock business. At slightly higher concentrations, the sensing system had a wide detection range (0.01–185 μM) with a detection limit of 3.8 nM. And at even lower concentrations, Lei et al. constructed copper and carbon composites with different morphologies than Xia et al. to detect RAC [144][45].5. Applications of 3D Sensors for Detections of Food Preservatives

Another typical food additive is nitrite, and too much of it might result in tissue hypoxia. To precisely monitor nitrite in food, He et al. developed an Ag nanoparticle (Ag NPs)-graphite carbon electrochemical sensor platform using femtosecond laser technology [69][46]. Thanks to the laser pulse treatment to create a complete 3D flower-like micro-nano structure and mixed with Ag NPs, which increases the conductivity of the composite, this electrochemical sensing exhibited a wide detection range (1–4000 × 10−6 M) and a low detection limit (0.117 × 10−6 M). Additionally, the sensor allows for highly sensitive dopamine detection and has remarkable reproducibility. Using a more cost-effective hydrothermal technique, Kogularasu et al. designed g-C3N4/Bi2S3 composites to detect nitrite [147][47]. Depending on 3D sea urchin architecture, g-C3N4/Bi2S3 can serve as the active centre and enrich NO2 for a stronger electrochemical signal. Meanwhile, g-C3N4/Bi2S3 exhibited a larger peak current than bare GCE and single component modified GCE. As a result, this detection platform for nitrite achieved an extremely wide linear detection range of 0.001–385.4 μM and a detection limit of 0.4 nM. Another material that proved effective in detecting nitrite was metal oxide. As ZnO has a strong binding energy of 60 meV and a wide band gap of 3.37–3.44 eV, it is thought to be the most easily tunable and structurally well-defined material among metal oxides. Cheng et al. designed uniformly dispersed spherical ZnO nanomaterials, which can be more likely to adsorb negatively charged No2− due to the zeta potential of +28.4 mV and RSD of 2.29% and utilized as electrochemical sensors for the detection and analysis of nitrite [148][48]. This 3D spherical ZnO-based sensing system was verified by chronoamperometry tests to have optimal linear detection ranges of 0.6 μM–0.22 mM and 0.46 mM–5.5 mM, a detection limit of 0.39 μM and a sensitivity of 0.785 μA μM−1 cm−2. Similarly, Somnet et al. obtained homogeneous spherical PdNPs@MIP using the molecularly imprinted technique to detect nitrosodiphenylamine, a derivative of nitrite [149][49]. PdNPs@MIP modified graphene electrodes for nitrosodiphenylamine detection with linear detection ranges of 0.01–0.1 μM (r2 = 0.996) and 0.1–100 μM (r2 = 0.992), the detection limit of 0.0013 μM. Direct growth of 3D arrays on the surface of GCE is also an idea to improve sensor performance. Lu et al. electrodeposited polymer polypyrrole (PPy) nanocones on the GCE surface and then loaded Co particles onto PPy [150][50]. Modified 3D electrodes demonstrate sensitive detection of nitrate encompassing a very wide linearity range of 2–3318 μM, the sensitivity of 2.60 μA μM−1 cm−2 accompanied with LOD of 0.35 μM. Han and co-workers reported a 3D flower-like MoS2 composite modified with silver nanoparticles to decorate glassy carbon electrodes to detect the food additive butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) [151][51]. Morphological analysis revealed that the silver particles are uniformly covered in 3D flowers-like MoS2, resulting in more active reaction sites and a greater capacity for electron transport. The improved electrode offers a broad linear detection range (1 × 10−9–1 × 10−4 mol/L) for BHA under ideal conditions, with incredibly low detection limits (7.9 × 10−9 mol/L). Especially in actual food detection, the distinct MoS2 structure given this sensing platform remarkable selectivity and 103% recovery. Another widely used food preservation agent is tert-butylhydroquinone (THBQ), and long-term THBQ intake might result in various bodily discomforts. Therefore, to meet the monitoring of THBQ residues in the food industry, using MOF-based electrochemical sensors is an effective method. For instance, a strategy to synthesize porous nitrogen-doped TiO2-carbon composites using MOF was reported by Tang et al. [152][52]. Its huge specific surface area and porous structure considerably improve the catalytic efficacy of GCE modified with TiO2/NC for THBQ. THBQ was quantified by the octahedral TiO2/NC with a wide linear range of 0.05–100 μM and a detection limit of 4 nM. Luo et al. obtained transparent ZnO/ZnNi2O4@porous carbon with a polyhedral structure by pyrolysis of Ni-ZIF-8, a typical MOF material. Then the amine aldol condensation process produced ZnO/ZnNi2O4@porous carbon@COFTM nanocomposite [153][53]. GCE modified with this nanomaterial made THBQ more susceptible to oxidation, so better detection results with a linear range of 47.85 nM–130 μM and a detection limit of 15.95 nM were attained. At the same time, the sensing platform can also detect paracetamol (PA) in the linear range of 48.5 nM–130 μM, with a detection limit of 12 nM. Balram et al. prepared the Co3O4 NRs/FCB (functionalized carbon black@Co3O4 nanorods) composite structure of spherical FCB uniformly spread over the rod-shaped spinel Co3O4 using the sonochemical method [154][54]. Screen printed carbon electrodes (SPCE) was modified with Co3O4 NRs/FCB composites for the ultra-sensitive detection of THBQ with a broad detection range (0.12–62.2 μM), an extremely low detection limit (1 nM) and an ultra-high sensitivity of 7.94 μA μM−1 cm−2.6. Applications of 3D Sensors for Detections of Foodborne Bacteria

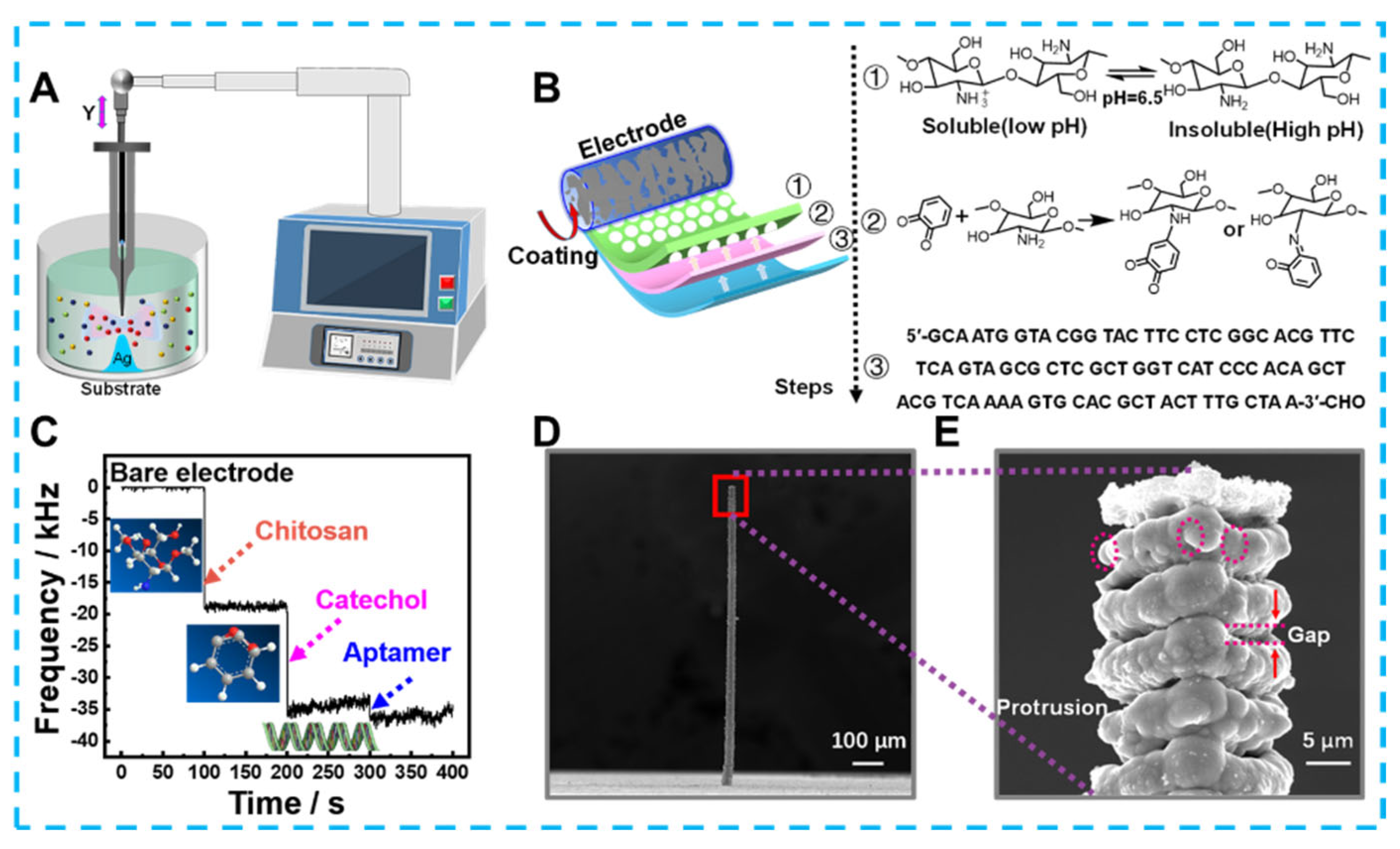

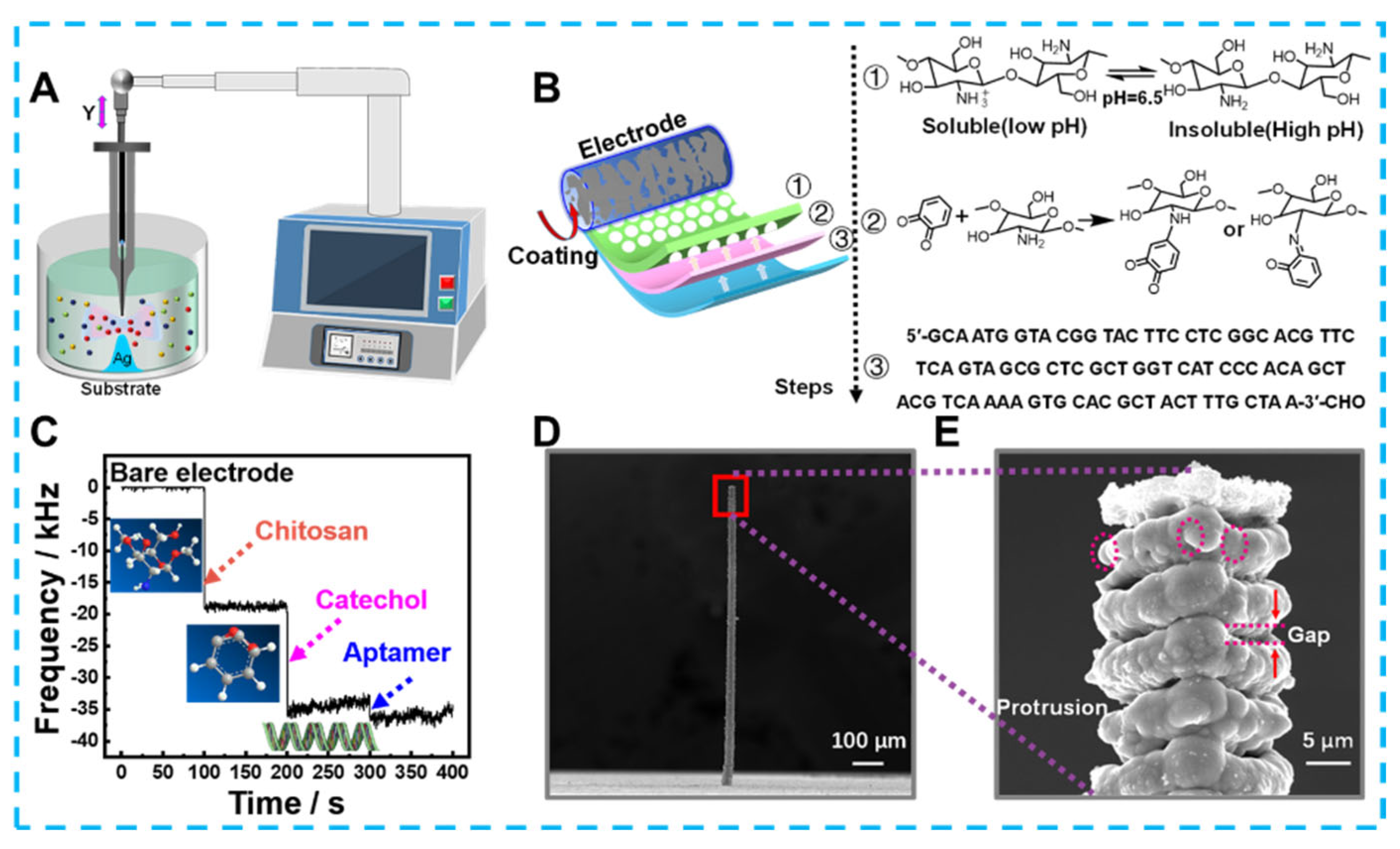

Developing emerging technologies for the electrochemical detection of bacteria could significantly reduce foodborne illnesses caused by bacterial contaminants. For example, Feng et al. prepared an electrochemical immunosensor based on Fe3O4@graphene composites to detect Salmonella in milk [167][55]. The 3D complex could immobilize monoclonal antibodies by loading a large amount of Au-NH bonds due to the growth of almost spherical Fe3O4 on a 2D graphene substrate, and Au NPs that also provided Au-NH could amplify an electrical signal. Electrochemical detection of Salmonella by these 3D composites was performed within the range of 2.4 × 102 and 2.4 × 107 cfu/mL with the detection limit of 2.4 × 102 cfu/mL. In addition, composite 3d materials containing graphene have shown high sensitivity in electrochemical sensing without immunoreactivity. For example, Fatema et al. focused on designing materials to prepare and apply Cu-Sn codoped BaTiO3-G-SiO2 (CuSnBTGS) to detect Rhizoctonia stolonifer [168][56]. CuSnBTGS had many mesopores and an ideal surface area, which N2 adsorption—desorption isotherms had confirmed was due to its mixed cubic sphere and lamellae structure. The rapid migration of electrons on the CuSnBTGS surface also resulted in a linear relationship between the sensing Rhizoctonia stolonifer concentration in the range of 50–100 μL, and the detection limit was 0.50 μL. Along with synthesizing 3D structured nanomaterials, designing 3-dimensional microstructured electrodes can also optimize the detection effect. As an example of a typical optimized planar electrode shown in Figure 1, Lai et al. created Ag micro-nano-pillars that resembled multilayer cakes using local electrochemical deposition [169][57]. The uneven surface of these nano-pillars formed a localized electric solid field that caused Cl− ions within the bacteria to flow out. And the Cl− ions were used to label bacteria in the pseudo-capacitive electrochemical sensor constructed using Ag micro-nano-pillars. Compared to flat structures and smooth Ag columns, Ag micro-nano-pillars with rough surfaces was more capable of inducing Cl− ions, as confirmed by COMSOL simulations. Therefore, the sensor achieves ultra-sensitive detection for Staphylococcus aureus in the linear range of 1–105 CFU mL−1 with a detection limit as low as1 CFU mL−1 and maintains specificity in the presence of nine other species of bacteria. In addition to the traditional colony count, detecting biomarkers is an essential indicator of bacterial viability and damage. Zheng et al. used hydrangea-shaped MoS2 modified by AuPd nanoparticles to design electrochemical aptamer sensors [170][58]. Meanwhile, porous Co-MOF and MCA 3D hybrid materials offer a clearly defined structure and reliable electrochemical characteristics. In particular, the structural advantage of a large specific surface area provides many sites for methylene blue (MB) loading. More active surfaces also offer the potential to penetrate many nucleotide chains driven by π–π stacking interaction and electrostatic adsorption interaction. Based on the above advantages, electrochemical aptasensors were developed to detect adenosine triphosphate (ATP) biomarkers. With reasonable use of the 3D structure of the active material and the signal label, not only is signal amplification achieved, but the detection range of 10 pM–100 μM and detection limits as low as 7.37 × 10−10 μM are the ideal embodiment of performance.

Figure 1. (A) The schematic diagram for preparing Ag micro−nano−pillar electrodes, (B) process of modifying electrodes, (C) Mass change of electrodes after each modification step recorded by microbalance, (D) scanning electron microscope image of 3D Ag microelectrode and (E) local morphology.

References

- Wang, Z.; Liao, F.; Guo, T.; Yang, S.; Zeng, C. Synthesis of crystalline silver nanoplates and their application for detection of nitrite in foods. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2012, 664, 135–138.

- Rassaei, L.; Marken, F.; Sillanpää, M.; Amiri, M.; Cirtiu, C.M.; Sillanpää, M. Nanoparticles in electrochemical sensors for environmental monitoring. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2011, 30, 1704–1715.

- Kaur, H.; Siwal, S.S.; Chauhan, G.; Saini, A.K.; Kumari, A.; Thakur, V.K. Recent advances in electrochemical-based sensors amplified with carbon-based nanomaterials (CNMs) for sensing pharmaceutical and food pollutants. Chemosphere 2022, 304, 135182.

- Curulli, A. Recent Advances in Electrochemical Sensing Strategies for Food Allergen Detection. Biosensors 2022, 12, 503.

- Moudgil, P.; Bedi, J.S.; Aulakh, R.S.; Gill, J.P.S.; Kumar, A. Validation of HPLC Multi-residue Method for Determination of Fluoroquinolones, Tetracycline, Sulphonamides and Chloramphenicol Residues in Bovine Milk. Food Anal. Methods 2019, 12, 338–346.

- Llamas, N.E.; Garrido, M.; Nezio, M.S.D.; Band, B.S.F. Second order advantage in the determination of amaranth, sunset yellow FCF and tartrazine by UV–vis and multivariate curve resolution-alternating least squares. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 655, 38–42.

- Pourreza, N.; Fat’hi, M.R.; Hatami, A. Indirect cloud point extraction and spectrophotometric determination of nitrite in water and meat products. Microchem. J. 2012, 104, 22–25.

- Ryvolová, M.; Táborský, P.; Vrábel, P.; Krásenský, P.; Preisler, J. Sensitive determination of erythrosine and other red food colorants using capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1141, 206–211.

- Rajapaksha, P.; Elbourne, A.; Gangadoo, S.; Brown, R.; Cozzolino, D.; Chapman, J. A review of methods for the detection of pathogenic microorganisms. Analyst 2019, 144, 396–411.

- Liu, S.; Zhao, K.X.; Huang, M.Y.; Zeng, M.M.; Deng, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, H.; Li, W.; Chen, Z. Research progress on detection techniques for point-of-care testing of foodborne pathogens. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 21.

- Chae, W.; Kim, P.; Hwang, B.J.; Seong, B.L. Universal monoclonal antibody-based influenza hemagglutinin quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Vaccine 2019, 37, 1457–1466.

- Karimi-Maleh, H.; Arotiba, O.A. Simultaneous determination of cholesterol, ascorbic acid and uric acid as three essential biological compounds at a carbon paste electrode modified with copper oxide decorated reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite and ionic liquid. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 560, 208–212.

- Fu, J.; An, X.; Yao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Sun, X. Electrochemical aptasensor based on one step co-electrodeposition of aptamer and GO-CuNPs nanocomposite for organophosphorus pesticide detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 287, 503–509.

- Choudhary, M.; Siwal, S.; Nandi, D.; Mallick, K. Single step synthesis of gold–amino acid composite, with the evidence of the catalytic hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) reaction, for the electrochemical recognition of Serotonin. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2016, 77, 72–80.

- Zhou, Y.L.; Yin, H.S.; Li, J.; Li, B.C.; Li, X.; Ai, S.Y.; Zhang, X.S. Electrochemical biosensor for microRNA detection based on poly (U) polymerase mediated isothermal signal amplification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 79, 79–85.

- Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Huang, K.-J.; Hou, Y.-Y.; Sun, X.; Li, J. Real-Time Biosensor Platform Based on Novel Sandwich Graphdiyne for Ultrasensitive Detection of Tumor Marker. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 16980–16986.

- Nikolaus, N.; Strehlitz, B. Amperometric lactate biosensors and their application in (sports) medicine, for life quality and wellbeing. Microchim. Acta 2008, 160, 15–55.

- Li, T.; Shang, D.; Gao, S.; Wang, B.; Kong, H.; Yang, G.; Shu, W.; Xu, P.; Wei, G. Two-Dimensional Material-Based Electrochemical Sensors/Biosensors for Food Safety and Biomolecular Detection. Biosensors 2022, 12, 314.

- Ronkainen, N.J.; Halsall, H.B.; Heineman, W.R. Electrochemical biosensors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1747–1763.

- Heinze, J. Ultramicroelectrodes in Electrochemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1993, 32, 1268–1288.

- Maduraiveeran, G.; Sasidharan, M.; Ganesan, V. Electrochemical sensor and biosensor platforms based on advanced nanomaterials for biological and biomedical applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 103, 113–129.

- Liu, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, W.; Qu, L.; Chen, S.; Wu, S. Electrospun strong, bioactive, and bioabsorbable silk fibroin/poly (L-lactic-acid) nanoyarns for constructing advanced nanotextile tissue scaffolds. Mater. Today Bio 2022, 14, 100243.

- Valiev, R. Nanomaterial advantage. Nature 2002, 419, 887–889.

- Piscitelli, A.; Pennacchio, A.; Longobardi, S.; Velotta, R.; Giardina, P. Vmh2 hydrophobin as a tool for the development of “self-immobilizing” enzymes for biosensing. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 46–52.

- Qiu, B.; Xing, M.; Zhang, J. Recent advances in three-dimensional graphene based materials for catalysis applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 2165–2216.

- Zou, C.E.; Yang, B.; Bin, D.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Yang, P.; Wang, C.; Shiraishi, Y.; Du, Y. Electrochemical synthesis of gold nanoparticles decorated flower-like graphene for high sensitivity detection of nitrite. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 488, 135–141.

- Li, X.; Lu, S.; Zhang, G. Three-dimensional structured electrode for electrocatalytic organic wastewater purification: Design, mechanism and role. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 445, 130524.

- Zhu, D.; Zhen, Q.; Xin, J.; Ma, H.; Tan, L.; Pang, H.; Wang, X. A free-standing and flexible phosphorus/nitrogen dual-doped three-dimensional reticular porous carbon frameworks encapsulated cobalt phosphide with superior performance for nitrite detection in drinking water and sausage samples. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 321, 128541.

- Park, S.-W.; Yun, E.-T.; Shin, H.J.; Kim, W.; Lee, J.; Kim, D.-W. Three-dimensional construction of electrode materials using TiC nanoarray substrates for highly efficient electrogeneration of sulfate radicals and molecular hydrogen in a single electrolysis cell. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 11705–11717.

- Bai, H.; Shi, G. Gas Sensors Based on Conducting Polymers. Sensors 2007, 7, 267–307.

- Kokulnathan, T.; Sakthi Priya, T.; Wang, T.-J. Surface Engineering Three-Dimensional Flowerlike Cerium Vanadate Nanostructures Used as Electrocatalysts: Real Time Monitoring of Clioquinol in Biological Samples. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 16121–16130.

- Kokulnathan, T.; Wang, T.-J. Synthesis and characterization of 3D flower-like nickel oxide entrapped on boron doped carbon nitride nanocomposite: An efficient catalyst for the electrochemical detection of nitrofurantoin. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 174, 106914.

- Wei, Z.; Zhu, W.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, N.; Suo, Y.; Wang, J. Conductive Leaflike Cobalt Metal-Organic Framework Nanoarray on Carbon Cloth as a Flexible and Versatile Anode toward Both Electrocatalytic Glucose and Water Oxidation. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 8422–8428.

- Zhang, L.; Tao, H.; Ji, C.; Wu, Q.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y. Sensitive and direct electrochemical detection of bisphenol S based on 1T&2H-MoS2/CNTs-NH2 nanocomposites. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 8203–8214.

- Wang, H.; Zhu, W.; Xu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Ma, M. An integrated nanoflower-like MoS2@CuCo2O4 heterostructure for boosting electrochemical glucose sensing in beverage. Food Chem. 2022, 396, 133630.

- Thenrajan, T.; Selvasundarasekar, S.S.; Kundu, S.; Wilson, J. Novel Electrochemical Sensing of Catechins in Raw Green Tea Extract via a Trimetallic Zeolitic Imidazolate Fibrous Framework. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 19754–19763.

- Tang, J.; Hu, T.; Li, N.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J.; Zheng, S.; Guo, J. Ag doped Co/Ni bimetallic organic framework for determination of luteolin. Microchem. J. 2022, 179, 107461.

- Balram, D.; Lian, K.Y.; Sebastian, N.; Al-Mubaddel, F.S.; Noman, M.T. Ultrasensitive detection of food colorant sunset yellow using nickel nanoparticles promoted lettuce-like spinel Co3O4 anchored GO nanosheets. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 159, 112725.

- Garkani Nejad, F.; Asadi, M.H.; Sheikhshoaie, I.; Dourandish, Z.; Zaimbashi, R.; Beitollahi, H. Construction of modified screen-printed graphite electrode for the application in electrochemical detection of sunset yellow in food samples. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 166, 113243.

- Chen, Y.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Sun, H.; Qiao, X.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Z. Novel ratiometric electrochemical sensing platform with dual-functional poly-dopamine and signal amplification for sunset yellow detection in foods. Food Chem. 2022, 390, 133193.

- Joseph, X.B.; Sherlin, V.A.; Wang, S.F.; George, M. Integration of iron-manganese layered double hydroxide/tungsten carbide composite: An electrochemical tool for diphenylamine H(*+) analysis in environmental samples. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113291.

- Ghalkhani, M.; Gharagozlou, M.; Sohouli, E.; Marzi Khosrowshahi, E. Preparation of an electrochemical sensor based on a HKUST-1/CoFe2O4/SiO2-modified carbon paste electrode for determination of azaperone. Microchem. J. 2022, 175, 107199.

- Xia, Y.; Hu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zeng, B. Molecularly imprinted ratiometric electrochemical sensor based on carbon nanotubes/cuprous oxide nanoparticles/titanium carbide MXene composite for diethylstilbestrol detection. Mikrochim. Acta 2022, 189, 137.

- Keerthi, M.; Kumar Panda, A.; Wang, Y.H.; Liu, X.; He, J.H.; Chung, R.J. Titanium nanoparticle anchored functionalized MWCNTs for electrochemical detection of ractopamine in porcine samples with ultrahigh sensitivity. Food Chem. 2022, 378, 132083.

- Lei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, L.; Li, J. Biochar-supported Cu nanocluster as an electrochemical ultrasensitive interface for ractopamine sensing. Food Chem. X 2022, 15, 100404.

- He, J.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L.; Li, X.; Hong, Q.; Zhu, W.; Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Z. Femtosecond Laser One-Step Direct Writing Electrodes with Ag NPs-Graphite Carbon Composites for Electrochemical Sensing. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2022, 7, 2200210.

- Kogularasu, S.; Sriram, B.; Wang, S.-F.; Sheu, J.-K. Sea-Urchin-Like Bi2S3 Microstructures Decorated with Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanosheets for Use in Food Preservation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 2375–2384.

- Cheng, Z.; Song, H.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Gao, S.; Huo, L. Non-enzymatic nitrite amperometric sensor fabricated with near-spherical ZnO nanomaterial. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 211, 112313.

- Somnet, K.; Soravech, P.; Karuwan, C.; Tuantranont, A.; Amatatongchai, M. A compact N-nitrosodiphenylamine imprinted sensor based on a Pd nanoparticles-MIP microsphere modified screen-printed graphene electrode. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 914, 116302.

- Lu, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, L.; Hui, N.; Wang, D. A sensitive electrochemical sensor based on metal cobalt wrapped conducting polymer polypyrrole nanocone arrays for the assay of nitrite. Mikrochim. Acta 2021, 189, 26.

- Han, S.; Ding, Y.; Teng, F.; Yao, A.; Leng, Q. Molecularly imprinted electrochemical sensor based on 3D-flower-like MoS2 decorated with silver nanoparticles for highly selective detection of butylated hydroxyanisole. Food Chem. 2022, 387, 132899.

- Tang, J.; Li, J.; Liu, T.; Tang, W.; Li, N.; Zheng, S.; Guo, J.; Song, C. N-Doped TiO2–Carbon Composites Derived from NH2-MIL-125(Ti) for Electrochemical Determination of tert-Butylhydroquinone. Food Anal. Methods 2022, 15, 2830–2839.

- Luo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Chen, S. An ultrafine ZnO/ZnNi2O4@porous framework for electrochemical detection of paracetamol and tert-butyl hydroquinone. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 906, 164369.

- Balram, D.; Lian, K.-Y.; Sebastian, N.; Al-Mubaddel, F.S.; Noman, M.T. A sensitive and economical electrochemical platform for detection of food additive tert-butylhydroquinone based on porous Co3O4 nanorods embellished chemically oxidized carbon black. Food Control 2022, 136, 108844.

- Feng, K.; Li, T.; Ye, C.; Gao, X.; Yue, X.; Ding, S.; Dong, Q.; Yang, M.; Huang, G.; Zhang, J. A novel electrochemical immunosensor based on Fe3O4@graphene nanocomposite modified glassy carbon electrode for rapid detection of Salmonella in milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 2108–2118.

- Fatema, K.N.; Areerob, Y.; Meng, Z.-D.; Zhu, L.; Oh, W.-C. Cu- and Sn-Codoped Mesoporous BaTiO3-G-SiO2 Nanocomposite for Bioreceptor-Free, Sensitive, and Quick Electrochemical Sensing of Rhizopus stolonifer Fungus. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2022, 4, 2053–2061.

- Lai, Q.; Niu, Q.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Long, M.; Liang, B.; Wang, F.; Liu, Z. An ultrasensitive bacteria biosensor using “multilayer cake” silver microelectrode based on local high electric field effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2022, 121, 013701.

- Zheng, R.; He, B.; Xie, L.; Yan, H.; Jiang, L.; Ren, W.; Suo, Z.; Xu, Y.; Wei, M.; Jin, H. Molecular Recognition-Triggered Aptazyme Sensor Using a Hybrid Nanostructure as Signal Labels for Adenosine Triphosphate Detection in Food Samples. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 12866–12874.

More