2. Prostate Cancer Epidemiology in Sexual Minorities

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in men and is the second-leading cause of cancer-related death following lung cancer

[1]. It is difficult to assess the exact incidence and prevalence of prostate cancer in sexual and gender minority groups, including GBM and TW, for multiple reasons. A substantial proportion of these individuals might be reluctant to disclose their sexual identity. In addition, large scale cancer surveillance surveys do not routinely collect sexual orientation and practices

[8][17].

Prostate cancer is mostly diagnosed in the 6th and 7th decade of life. Several studies suggest that the mean age of prostate cancer diagnosis is younger in gay men than in heterosexuals, although it still mainly affects middle-aged populations in their 60s

[9][18]. However, several factors need to be considered which might have led to sampling bias in studies of gay men with prostate cancer. A significant, but unknown, number of sexual minorities died during the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s. Moreover, individuals who have gone on to be diagnosed with disease could have limitations reporting their sexual orientation and related health concerns due to long-standing barriers in a historically heteronormative system

[4]. Studies have shown that older men from sexual minority groups might be less likely to declare their sexual orientation as gay, which can also cause bias in sampling. Collected data from Gallup surveys from more than 1.6 million adults between 2012 and 2016 revealed that while 2.4% for baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) identified as LGBT, this number was 7.8% for millennials (born between 1980 and 1998)

[10][19].

The association between HIV/AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) and prostate cancer have previously been investigated. Several studies have proposed that HIV-positive men are at higher risk of prostate cancer than HIV-negative

[11][12][29,30]. However, studies performed during the era of ARV treatment and PSA screening have shown the opposite trend. The US HIV/AIDS Cancer Match Study, which studied men who met the clinical definition for AIDS, found no difference in prostate cancer incidence compared to the general population before the introduction of the PSA test and ARV treatment (before 1992). However, during the PSA era (1992–2007), there was a significant reduction in the risk, with a twofold decrease among men with AIDS. Of note, this study also revealed that PSA testing rates were lower among low-income HIV-infected men

[13][31].

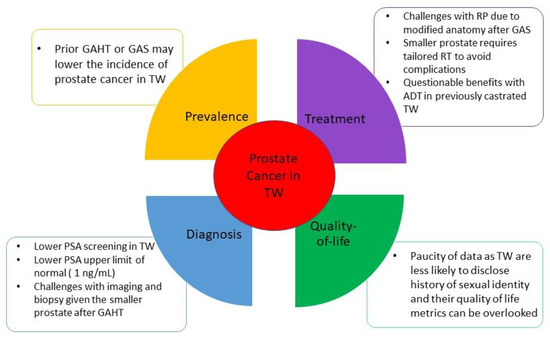

Incidence of prostate cancer in the transgender women community (i.e., who are assigned male at birth) is poorly understood. Bertoncelli Tanaka et al. performed a non-systematic review of the literature related to PC in transgender women by including 10 case reports, four specialist opinion papers, six cohort studies, and four systematic reviews. They concluded that the likelihood of developing prostate cancer for TW who are not receiving gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) or who have not undergone gender-affirming surgery (GAS), and gender non-conforming individuals (who may never commence GAHT or have GAS) is similar to that of cis-gender males. However, transgender women on GAHT or following GAS have lower incidence of prostate cancer than age-matched cis-male counterparts

[5]. Given the paucity of data in the literature regarding incidence of prostate cancer in transgender women, it is challenging to draw conclusions regarding potential disparities in incidence of prostate cancer in this population (

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Specific considerations for prostate cancer in transgender women. Abbreviations: ADT: androgen deprivation therapy. GAHT: gender-affirming hormonal therapy. GAS: gender-affirming surgery. PSA: prostate specific antigen. RP: radical prostatectomy. RT: radiation therapy. TW: transgender women.

3. Prostate Cancer Screening and Diagnosis in Sexual Minorities

Prostate cancer screening using PSA testing is intended to detect the early-stage cancer that may be treated and potentially cured. Nonetheless, controversy surrounding PSA screening remains, regarding whether testing reduces disease-specific morbidity and/or mortality in the general population, or merely leads to invasive diagnostic procedures and associated complications of treatments without prolonging life

[14][32]. In 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) allocated a grade D recommendation to PSA testing (recommendation against PSA-based screening for prostate cancer) which was later changed to grade C (advocating for an individualized approach to screening) in 2018 for men aged 55–69 years. Both USPSTF and the American Urological Association (AUA) emphasize the necessity of a risks versus benefits discussion and shared decision-making with patients

[15][16][33,34]. However, the pattern of prostate cancer screening in sexual minorities remains obscure.

PSA screening literature among gay and bisexual men lacks consistent collection and analysis of mediators and confounding variables, which may impact the results. In the California Health Interview Survey, gay/bisexual men had a lower likelihood of having up-to-date PSA testing compared with heterosexuals, when adjusted for race/ethnicity, education, or language proficiency. Use of this test by gay/bisexual African Americans was 12–14% less than that of straight African Americans and 15–28% less than that of gay/bisexual Whites in this study

[17][37]. In another study by Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., initial analyses suggested that sexual minority men had a significantly lower odds of having PSA testing compared to heterosexual men. However, after adjusting for sociodemographic variables, the observed difference was no longer statistically significant

[18][8]. Further epidemiological studies are needed to fully comprehend the relationships between sexual orientation, demographic characteristics, and PSA screening.

Transgender participants in Ma et al.’s study were less likely to have PSA screening

[19][35]. This is supported by findings from two additional studies that indicated that transgender women were less likely than cis-gendered men to ever have a risks versus benefits discussion about PSA screening with healthcare providers

[20][21][38,39]. It is plausible that transgender women may find it challenging to disclose their personal sexual identity history to primary care physicians, leading to the possibility of not being offered the opportunity to talk about PSA screening when it is appropriate

[5]. There is also a lack of international consensus in different guidelines regarding screening of TW for prostate cancer. Experts have recommended PSA testing discussion before starting GAHT or during GAHT should be offered to those who are eligible based on national guidelines similar to a cis-gendered man

[22][40].

Nonetheless, given that PSA levels drop significantly after initiating GAHT, the upper limit of normal for PSA in the TW population is considered 1 ng/mL

[5][22][5,40]. Prostate biopsy in TW following GAS is not contraindicated as studies indicate biopsy can safely be done with a transneovaginal ultrasound probe similar to standard transrectal ultrasound and biopsy. However, anatomical modifications following GAS and also the smaller prostate size secondary to GAHT needs to be taken into consideration

[23][41]. Cases with PSA more than 1 ng/mL can be evaluated with multiparametric prostate MRI (MP-MRI) and the ones with PI-RADS (Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System) ≥3 lesion will be considered for biopsy

[24][42]. Hugosson et al. found in a study published in NEJM that MRI-directed targeted biopsy is helpful to detect prostate cancer in a low PSA population; although it can miss clinically non-significant diseases which can reduce the risk of overdiagnosis

[25][43]. PSA density (PSAd) can serve as a useful tool in addition to PI-RADS for identifying individuals who require a biopsy to diagnose prostate cancer. Friesbie et al. demonstrated that PSAd, with a cutoff of 0.1 ng/mL/cc, can stratify the risk of prostate cancer in a complementary way with prostate MP-MRI

[26][44].

4. Prostate Cancer Treatment in Sexual Minorities

Treatment options for localized prostate cancer include external beam radiation therapy (RT) with or without brachytherapy, brachytherapy alone, radical prostatectomy, or active surveillance. These options are recommended based on the risk stratifications provided by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Urological Association, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of Urologic Oncology

[27][28][45,46]. The decision regarding treatment is arrived at after a discussion with the patient, weighing the potential risks against the benefits. A study utilizing an online prostate cancer discussion board demonstrated that gay men were more worried about the negative impacts of treatment and the availability of psychological and emotional support, whereas straight men were more interested in exploring the different treatment options available to them

[29][47]. These concerns by gay men may impact treatment preferences, but additional research is required to substantiate this possibility.

It is unclear if treatment patterns in the GBM community differ from heterosexual men. For example, there have been reports that Gleason scores were found to be significantly lower in GBM treated for prostate cancer than in heterosexual men

[30][31][24,36]. In a study performed by Murphy et al. in Chicago, it was found that men who are HIV-positive are equally likely to receive treatment for prostate cancer. However, they are less likely to undergo a radical prostatectomy and more likely to receive overtreatment compared to men who are HIV-negative

[32][48]. Use of ARV treatment for HIV has been suggested to be protective in prostate cancer

[33][49].

The Restore-1 trial evaluated the experiences of discrimination in treatment faced by prostate cancer patients who identify as sexual and gender minorities. The study involved 192 participants, gay, bisexual, or transgender, in the United States. The participants were recruited from North America’s largest online cancer support group and were asked to complete an online survey. Discrimination in treatment was measured using the Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS), which had been adapted for use in medical settings

[34][35][54,55]. Almost half of the participants (46%) reported experiencing at least one discriminatory behavior, including being talked down to (25%), receiving poorer care than other patients (20%), being treated as inferior (19%), and having providers appear afraid of them (10%). Most participants rated the discrimination as rare or occasional, but 20% reported it as more common. The discrimination was mostly attributed to the participants’ sexual orientation, and to providers being arrogant or too pressed for time

[36][56]. It remains unclear what effects on prostate cancer treatment these forms of discrimination have on sexual minorities.

Prostate cancer treatment in transgender women is generally similar to treatment received by cis-gender men

[5]. Radical prostatectomy after GAS is not contraindicated

[23][41]. As some transgender women may have undergone penectomy coupled with neovagina creation, there are resulting changes in anatomic landmarks

[37][57]. Therefore, a treating surgeon must be aware of the altered anatomy between the prostate, neovagina, and rectum to perform a successful radical prostatectomy

[38][58]. Moreover, the prostate is usually atrophied if a patient has undergone previous GAHT. In a small study with 14 patients on estrogen therapy, average prostate volume was 14.19 cm

[39][59], which makes the landmarks for surgery less clear and radical prostatectomy more technically challenging. A smaller prostate requires tailored care with radiation therapy as well. Excessive radiation should be avoided as it can lead to neovaginal stenosis

[23][41]. In cases of brachytherapy, seed implantation in the small prostate gland can increase the risk of toxicity to adjacent organs

[40][60]. In TW who already are surgically castrated or have castrate levels of testosterone secondary to GAHT, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) will not provide significant benefits. Second generation androgen receptor targeted therapies, such as enzalutamide or abiraterone, might be better options in this patient population

[23][41]. However, there is no clear date to prove their benefit.