1. Introduction

Critically ill patients commonly suffer from extensive skeletal muscle atrophy and a generalized reduction in muscle strength, a condition termed intensive care unit-acquired weakness (ICUAW)

[1]. Precisely, ICUAW is defined as a newly acquired weakness triggered by critical illness, immobilization and prolonged mechanical ventilation with a Medical Research Council Sum Score (MRC-SS) < 48

[2]. The presence of a flaccid, symmetrical paresis of the upper and lower extremities with sparing of the facial muscles and cranial nerves is considered a hallmark symptom in ICUAW

[3]. Hereby, other neuromuscular complications with similar clinical symptoms (e.g., entrapment neuropathies due to prolonged bed rest and steroid-induced myopathies) have to be excluded. In ICUAW, the long-term outcome can be worsened by up to five years, even in milder cases with subtle levels of muscle weakness

[4]. The pathophysiological correlate comprises the critical illness myopathy (CIM), the critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP) and the combined critical illness polyneuromyopathy (CIPNM)

[5]. In daily clinical practice, ICUAW is predominantly diagnosed based on clinical examinations

[6][7][6,7]. However, due to prolonged sedation, delirium and cognitive impairment, patient compliance is frequently disturbed and clinical assessment often limited

[8]. Therefore, many compliance-independent diagnostic attempts including nerve conduction studies (NCS), electromyography (EMG), muscle biopsies, body fluid and in vivo biomarkers have been investigated to detect and monitor ICUAW

[9][10][11][12][9,10,11,12]. Unfortunately, their applicability in daily clinical practice is currently limited

[13]. To overcome the above-mentioned limitations, various medical imaging techniques have been evaluated in ICUAW and associated neuromuscular complications, with promising results. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of skeletal muscles demonstrates distinctive alterations in the involved muscles, including hyperintensity in T2-weighted and short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences

[14][15][16][14,15,16]. These signal patterns are suggestive of edema as the underlying pathomorphological substrate and have been demonstrated to resolve in parallel to clinical recovery of several months

[17][18][17,18]. Persistent MRI alterations correlate with prolonged weakness and disability

[19]. In a single case, myosin loss has been proven by histopathology in a biopsy from muscle with the aforementioned imaging abnormalities

[20]. Muscle MRI, and STIR sequences, in particular, may be useful in discriminating patients with critical illness myopathy from patients with immune mediated neuropathy

[21]. Despite a slowly-growing interest in MRI as a potential diagnostic tool for patients at risk of ICUAW, the number of published cases is still very limited and the effort to conduct MRI studies is remarkable in the affected patient population. In contrast, ultrasound has been proven to be a valuable diagnostic tool for many different diagnostic approaches in intensive care medicine

[22][23][22,23]. Especially for the assessment of pathologies of muscles and nerves, neuromuscular ultrasound (NMUS) is an established complementary method

[24]. NMUS offers several advantages such as widespread availability, real-time assessment and non-invasiveness, and it can be used even in non-compliant patients

[25]. In the last few years, extensive research has been conducted to investigate the value of NMUS in ICUAW and associated neuromuscular complications

[26][27][28][26,27,28]. Hereby, NMUS might be of particular value for the detection, monitoring and, at least in part, outcome prediction in cases of ICUAW

[29][30][29,30]. Beyond ultrasound, subsequent computational image analysis has also emerged in the last decade and might offer further improvement in diagnostic performance in ultrasonographic assessment

[31][32][31,32].

2. Skeletal Muscles

Skeletal muscles vary in their form, size and architectural structure within and between individuals. Therefore, it is not surprising that sonographic images of skeletal muscles can also have some individual characteristics. In healthy subjects, the general ultrasonographic depiction of skeletal muscles appears black with a variable proportion of echo-rich connective tissue structures within. This picture is often called a “starry night” appearance

[25]. In the absence of connective tissue, muscle fibers reflect lesser soundwaves back to the ultrasound probe, resulting in a relatively dark ultrasound image with a low echogenicity. It must be noted that healthy skeletal muscles can vary in their echogenicity, even without a pathological reason

[29][32][29,32]. Most frequently, limb skeletal muscles have been assessed with NMUS in regard to investigating ICUAW. All studies listed in

Table 1 are single-center trials, most of them with a prospective design. The study cohorts are heterogeneous with relatively small patient numbers ranging from 17 to 95. In particular, the QF and the tibialis anterior muscle (TA) have been examined frequently

[26][27][28][29][30][33][34][26,27,28,29,30,44,45]. Besides limb skeletal muscles, the diaphragm has also been targeted by numerous workgroups and will be discussed later

[35][36][37][46,47,48]. Only a few trials assessed intercostal, abdominal or deep back muscles with ultrasound.

Table 1. Non-systematic selection of studies investigating skeletal muscles with NMUS in ICUAW within the last 10 years. BB: biceps brachii muscle. BRA: brachialis muscle. BR: brachioradialis muscle. CB: coracobrachialis muscle. CSA: cross-sectional area. EDL: extensor digitorum longus muscle. FCR: flexor carpi radialis muscle. FE: forearm extensor muscles. FIM: Functional Independence Measure. IC: intercostal muscles. ICUAW: intensive care unit-acquired weakness. LOS: length of stay. ME: muscle echogenicity. MMT: Manual Muscle Testing. MRC-SS: Medical Research Council Sum Score. mRS: modified Rankin Scale. PA: pennation angle. QF: quadriceps femoris muscle. RF: rectus femoris muscle. TA: tibialis anterior muscle.

3. Peripheral Nerves

The nerve ultrasound has become an established complementary diagnostic approach in many different disease entities and syndromes, including peripheral nerve injuries, entrapment neuropathies and (poly)neuropathies

[24]. At the ICU, sonographic assessment of the optic nerve sheath diameter can help to non-invasively detect increased intracranial pressure

[39][50]. However, in regard to ICUAW, data on the diagnostic value of peripheral nerve ultrasound are limited (

Table 2). Most of the corresponding studies are single-center prospective clinical trials with a mixed patient population. Nerves of the upper and lower extremities have been assessed describing changes in nerve thickness, nerve CSA and nerve echogenicity. In one study intraneural vascularization was also quantified

[34][45].

Table 2. Non-systematic selection of studies investigating peripheral nerves with NMUS in ICUAW. CSA: cross-sectional area. ME: muscle echogenicity.

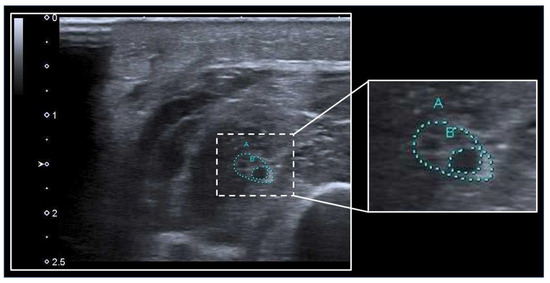

The nerve CSA is one of the most frequently assessed neural parameters in regard to ICUAW. Hereby, the peripheral nerve can be depicted in sonographic short axis and its circumference can be manually traced (

Figure 12). However, data on measurements of the nerve CSA in ICUAW are sparse and partly inconsistent, whereby nerve CSA does not seem useful in distinguishing between patients with and without ICUAW but may be of value in distinguishing patients with a predominant presentation of CIP from patients with CIM

[33][34][40][41][44,45,51,52]. In general, an increased nerve CSA seems to correlate with the duration of mechanical ventilation and days spent at the ICU

[41][52].

Figure 12. Assessment of nerve CSA with ultrasound. The median nerve (A) at the mid to proximal forearm is surrounded by muscles and can be identified by the heterogeneous “honeycomb” pattern within the echorich perineurium. A swollen fascicle (B) within the nerve depicts as a hypoechogenic area. The nerve CSA can be calculated using the tracing function of the ultrasound machine.

Nerve echogenicity is another parameter that can be assessed using NMUS. Hereby, the overall brightness of the peripheral nerve is obtained. Similarly to with the nerve CSA, evidence is sparse in regard to ICUAW and associated subtypes. In CIP, a significant decrease in nerve echogenicity has been described

[34][45], which is contrary to findings from patients with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathies, where the disease severity correlates with a higher nerve echogenicity

[43][54]. However, the echogenicity of peripheral nerves seems unsuitable in distinguishing CIP from other polyneuropathies

[42][53].

4. Diaphragm

The diaphragm is considered the most important striated skeletal muscle in maintaining ventilation

[44][55]. Neuromuscular diseases affecting diaphragmatic muscle activity can, therefore, significantly alter both respiratory activity and gas exchange. Critically ill patients are frequently affected by paresis of the diaphragm, as even short-term mechanical ventilation is considered a key risk factor for ventilator-induced diaphragmatic dysfunction (VIDD) through the induction of muscle fiber atrophy

[45][56]. In addition, lower diaphragmatic muscle mass has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of weaning failure and worsened outcome

[46][57]. In recent years, sonography of the diaphragm has been intensively investigated as a possible diagnostic method for VIDD and is now considered a valid, easily reproducible tool with prognostic significance

[39][50]. In particular, diaphragmatic ultrasound has been used to investigate both static (diaphragmatic thickness) and dynamic (thickening fraction, maximum diaphragmatic excursion) parameters

[36][37][47,48]. Furthermore, diaphragm echogenicity and tissue Doppler imaging have recently also been proposed as possible surrogates for diaphragm function

[47][48][58,59]. Although VIDD and ICUAW are common in critically ill ICU patients, the interplay between these two entities remains unclear

[49][50][60,61]. Irrespective of this, the simultaneous presence of ICUAW and VIDD is associated with a higher risk of weaning failure, compared to the presence of one of these conditions alone

[51][52][62,63]. However, the value of diaphragmatic sonography as a surrogate parameter for generalised limb muscular weakness in ICUAW seems questionable. Jung et al. were able to demonstrate concomitant VIDD in 80% of a cohort of 40 ICUAW patients, but without correlation between diaphragmatic ultrasound parameters and limb muscle strength

[53][64]. This is in line with results by Vivier and co-workers, who were also unable to show a significant correlation between the parameters of diaphragmatic dysfunction and limb muscle strength

[54][65]. In a recent study, a decrease in diaphragmatic muscle thickness was observed in ICU patients, but without a significant difference between patients with and without ICUAW

[26].

5. Parameters of Muscle Quantity and Their Diagnostic Value for ICUAW

Critically ill patients frequently suffer from an early and progressive reduction in muscle mass. A recent meta-analysis suggests that a daily loss of about 2% can be estimated, whereby ultrasound is the most frequent used method to detect and monitor muscle degradation

[55][66]. Hereby, surrogate parameters for the quantification of muscle mass are the muscle layer thickness (MLT) and the muscle CSA

[56][67]. The MLT is usually determined in sonographic short axis as the maximum vertical diameter of muscle tissue within the muscle fascia. The MLT has been validated in clinical trials and anatomical studies with excellent intra- and interrater reliability

[57][58][59][60][68,69,70,71]. However, in critically ill patients, estimation of muscle mass by a single MLT measure might be insufficient

[61][72]. In contrast, the MLT seems suitable for the repetitive assessment and monitoring of muscle wasting within the ICU stay

[62][63][64][65][73,74,75,76]. Recent evidence suggests that the loss of muscle mass is more severe in critically ill patients with ICUAW

[30][62][30,73]. For the prediction of patient outcome, MLT has been shown to predict prolonged intensive care treatment and functional outcome

[65][66][76,77]. Furthermore, a reduction in MLT is associated with an increased mortality in ICUAW patients

[30].

Similarly to with the nerve CSA, the skeletal muscle CSA can be calculated to estimate muscle mass. Hereby, the anatomical rather than the physiological muscle CSA is measured

[67][33]. Analogous to the MLT, in NMUS the muscle CSA is measured in the sonographic short axis view of superficial limb skeletal muscles such as the biceps brachii muscle (BB), QF and TA

[12][62][63][64][12,73,74,75]. Some muscles such as the QF cannot be depicted fully in one image frame, so the individual muscle components (in the case of the QF: rectus femoris muscle, vastus intermedius muscle, vastus lateralis and vastus medialis muscles) have to be evaluated separately. Similarly to with the MLT, a decrease in muscle CSA of up to 30% has been demonstrated in ICU patients after several days of critical illness

[12][63][65][12,74,76], whereby patients with ICUAW seem to have greater losses of muscle mass compared to patients without ICUAW

[62][68][73,78]. The morphological and molecular equivalents of these sonographic observations include muscle fiber atrophy, necrosis and muscle protein breakdown

[12][69][12,79]. Furthermore, sonographic assessment of the muscle CSA can help to predict patient outcome. A reduction in muscle CSA has been shown to correlate with a significant reduction in muscle force and function

[63][65][74,76]. Overall, a reduction in muscle mass during critical illness seems to be associated with increased mortality in patients with ICUAW

[30][68][30,78].

6. Parameters of Muscle Quality and Their Diagnostic Value for ICUAW

The ultrasonographic brightness of a muscle can be described by the muscle echogenicity (ME). Muscle tissue from healthy subjects is usually relatively dark in appearance with a variable degree of interspersed bright echo signals from intramuscular connective tissue. Hereby, most of the ultrasound waves pass through the muscle tissue without being reflected. The brighter the muscle appears the more ultrasound waves are reflected back to the transducer. However, neuromuscular disorders can alter the ME in many different ways, including heterogeneous patterns of hyper- and hypoechogenicities

[25]. In contrast, ICUAW and associated neuromuscular disorders seem to increase the brightness of the entire muscle during critical illness

[28].

Most studies investigating ME in critically ill patients use the so-called greyscale analysis. A computer-based assessment of digitally stored ultrasound images allows quantification of image brightness by calculating the greyscale values of pixels within a defined region of interest. This method is, mostly, not implemented in current ultrasound machines, so quantification of ME using greyscale analysis requires a semi-automated secondary assessment by the examiner. Greyscale analysis has been validated in non-ICU and ICU patients with neuromuscular disorders

[32][70][32,80], whereby the accuracy depends on the size of the measured image area

[71][81]. Furthermore, software-based greyscale analysis has also been investigated in patients with ICUAW

[29][34][38][29,45,49]. Hereby, this method seems unsuitable in detecting ICUAW, and the correlation with clinical outcome data was low

[29][34][29,45]. In contrast, Naoi et al. reported a specificity of about 75% and a sensitivity of 69.2% for upper arm ME in detecting ICUAW, but without further specification of significant differences in ME between patients with and without ICUAW

[38][49].

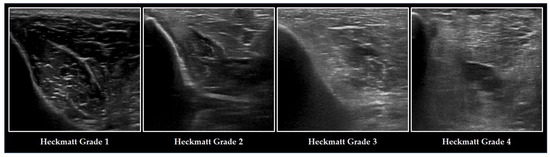

Another method to assess ME is semi-quantitative grading using the Heckmatt Scale (

Figure 23). Introduced by Heckmatt and coworkers in 1982, this four-point scale relies on the visual assessment of ME and bone echotexture

[72][82]. The brighter the muscle and the lower the bone echogenicity, the higher the grading. The Heckmatt Scale demonstrates good reliability

[32] and has been evaluated in critically ill patients

[28]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the Heckmatt Scale can be a useful tool to identify patients with ICUAW

[10][27][29][10,27,29]. Recent evidence suggests that the Heckmatt Scale might be superior to software-based greyscale analysis for the assessment of ME in ICUAW

[29], but inherent limitations of this visual approach must always be kept in mind

[31].

Figure 23. Ultrasonographic changes of the TA and the adjacent tibia in ICUAW graded with the Heckmatt Scale. The image on the left refers to a healthy individual, graded with lowest Heckmatt grade 1. Muscle tissue is classically dark with some bright echo signals from connective tissue. In critical illness (from the second left image) and especially in patients with ICUAW (from the second right image), muscle tissue becomes more echointense (Heckmatt grade 2) and the bone echo begins to become blurry (Heckmatt grade 3), until it has nearly vanished (Heckmatt grade 4).

Furthermore, assessment of ME can help to predict patient outcome. Several studies demonstrated that an increase in ME was correlated with the severity of muscle weakness and overall impairments in functional patient outcome

[29][38][63][65][29,49,74,76]. The presence of increased ME has also been previously associated with increased mortality in patients with CIPNM

[27].