Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Rafael Antonio Nascimento Ramos and Version 2 by Camila Xu.

Species within the genus Ixodiphagus (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) are natural parasitoid wasps of ticks (Acari: Ixodida), which were first described more than a century ago, in Haemaphysalis leporispalustris from Texas, United States (USA).

- Ixodiphagus hookeri

- biological control

- ixodid

- argasid

1. Introduction

Species within the genus Ixodiphagus (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae) are natural parasitoid wasps of ticks (Acari: Ixodida) [1], which were first described more than a century ago, in Haemaphysalis leporispalustris from Texas, United States (USA) [2]. The etymology of the genus name Ixodiphagus (from Greek ixod = tick and phage = eater) alludes to its parasitoid behavior. After its first description, other species of “tick eaters” within this genus were formally described worldwide [3][4][5][6][3,4,5,6].

Currently, at least ten species of these parasitoids are considered valid, namely Ixodiphagus texanus Howard, 1907; Ixodiphagus hookeri Howard, 1908; Ixodiphagus mysorensis Mani, 1941; Ixodiphagus hirtus Nikolskava, 1950; Ixodiphagus theilerae Fielder, 1953; Ixodiphagus biroi Erdos, 1956; Ixodiphagus sagarensis Geevarghese, 1977; Ixodiphagus taiaroaensis Heath and Cane, 2010; Ixodiphagus sureshani Hayat and Islam, 2011; and Ixodiphagus aethes Hayat and Veenakumari, 2015. These insects are small, generally measuring less than 1 cm in length, blackish in color, and exhibiting the typical appearance of members of the superfamily Chalcidoidea, and display similar biological and ecological features [7].

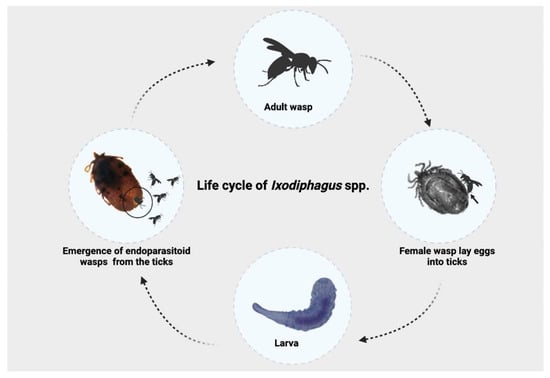

Despite being known for over a century, many knowledge gaps remain about the biology of these parasitoid wasps, with most information limited to I. hookeri [5][8][5,8]. The life cycle of these wasps starts when gravid females lay eggs inside the tick’s body. After an incubation period, the larvae hatch and feed on the internal content of the tick [7]. Approximately 30–57 days after oviposition, new adult male and female wasps emerge from the dead tick, mating and continuing their life cycle [9]. Based on this life cycle, the use of Ixodiphagus spp. as an agent for biological control of ticks has inspired the interest of the scientific community [10]. In addition, populations of I. hookeri may have different developmental times, parasitism rates, and host preferences according to the geographical area of occurrence [10], which may explain the failure, or the limited efficacy, of these wasps in the control of ticks in field studies [11][12][11,12].

2. Biology of Ixodiphagus spp. and Geographic Distribution

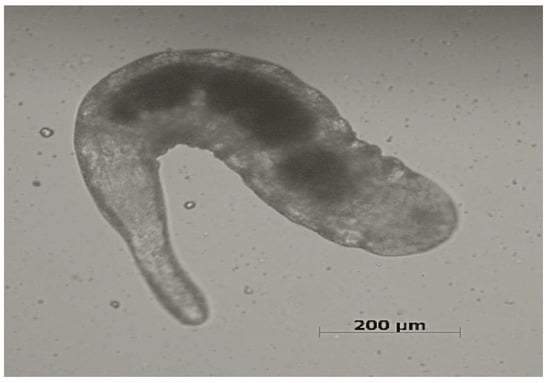

Information on the biology of Ixodiphagus species is insufficient and mainly limited to experimental studies [10]. The entire life cycle ranges from 28 to 70 days, and starts when female wasps lay eggs into ticks through the penetration of their ovipositor into the tick’s body (Figure 1). After hatching, larvae (Figure 2) develop inside the tick. While no information is available about the pupal stage, adult wasps emerge from their tick hosts through a hole at the posterior end, with mating occurring soon after the emergence [9]. There have been no studies assessing the number of Ixodiphagus eggs released by females in natural conditions. However, based on experimental studies, it is estimated that during the entire life span, I. hookeri and I. texanus lay about 120 and 200 eggs, respectively [13][14][23,24].

Figure 1.

Life cycle of

Ixodiphagus

spp.

Figure 2.

Ixodiphagus

sp. larva in a

Rhipicephalus sanguineus

s.l. tick (Scale bar = 200 μm).

Table 1.

Distribution of

Ixodiphagus

spp. parasitizing different tick species in the world.

| Parasitoid | Tick | Tick Life Stage | Country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. texanus | H. leporispalustris | Nymph | United States | [2] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus | Nymph | United States | [31][41] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus, D. marginatus | Nymph | United States | [9] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus | Nymph | France | [32][42] |

| I. hookeri | H. concinna, D. reticulatus, D. venustus, R. sanguineus |

NA | France | [33][43] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus | Nymph | Brazil | [34][44] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus | NA | India | [35][45] |

| I. hookeri | D. nitens | NA | United States | [36][46] |

| I. hookeri | D. variabilis | NA | United States | [11] |

| I. hookeri | H. aegyptium | NA | South Africa | [37][47] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus | Nymph | Nigeria | [38][48] |

| I. hookeri | I. cookei | Nymph | United States | [39][49] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus | NA | United States | [40][50] |

| I. texanus | H. leporispalustris | Nymph | United States | [41][51] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus | Nymph | United States | [42][52] |

| I. mysorensis | Ornithodorus sp. | NA | India | [30][40] |

| I. texanus | I. persulcatus | Nymph | Russia | [43][53] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus | Nymph | Czech Republic/Slovakia (Czechoslovakia) | [44][54] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus | Nymph | Kenya | [45][55] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus | Nymph | Africa | [46][56] |

| Ixodiphagus sp. | H. bancrofti, H. bremneri, I. holocyclus, I. tasmani | NA | Australia | [47][57] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus | NA | Indonesia | [48][58] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus | Nymph | Malaysia | [49][59] |

| I. texanus | H. leporispalustris | Larva, Nymph | Canada | [50][60] |

| I. hookeri | I. dammini | Nymph | United States | [51][21] |

| I. hookeri | H. punctata | Nymph | Spain | [52][61] |

| I. hookeri | A. variegatum | Nymph | Kenya | [53][62] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus | NA | France | [54][63] |

| I. texanus | I. dammini | Nymph | United States | [55][64] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus | Nymph | Mexico | [56][65] |

| I. hookeri | I. scapularis | Nymph | United States | [57][66] |

| I. hookeri | I. scapularis | Nymph | United States | [15][25] |

| I. hookeri | A. variegatum | Nymph | Kenya | [58][67] |

| I. hookeri | I. scapularis | Nymph | United States | [19][29] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus | Nymph | Venezuela | [59][68] |

| I. hookeri | A. variegatum | Nymph | Kenya | [27][37] |

| I.hookeri | H. concinna | Nymph | Slovakia | [16][26] |

| I. taiaroaensis | I. uriae, I. eudyptidis | Larva, Nymph | New Zealand | [60][69] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus | Nymph | Germany | [10] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus | Nymph | Netherlands | [22][32] |

| I. hookeri, I. texanus | R. sanguineus, Amblyomma sp. | Nymph | Brazil | [61][70] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus | Nymph | France | [22][32] |

| I. hookeri, I. texanus | R. sanguineus | Nymph | Panama | [62][71] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus | Nymph, Adult | Italy | [3] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus | Nymph | Slovakia | [63][22] |

| Ixodiphagus sp. | R. sanguineus | Nymph, Adult | Brazil | [4] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus | Nymph | Finland | [5] |

| I. hookeri | R. sanguineus | Nymph | United States | [64][72] |

| I. hookeri | R. microplus, I. persulcatus, D. silvarum, H. concinna |

Adult | Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Russia | [29][39] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus | Larva, Nymph | Netherlands | [8] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus, H. concinna | Nymph | Slovakia | [1] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus | Nymph | France | [25][35] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus | Nymph | United Kingdom | [65][73] |

| I. hookeri | A. nodosum | Nymph, Adult | Brazil | [66][74] |

| I. hookeri | I. ricinus | Nymph | Hungary | [6] |

NA: Not available.