Urban fragilWity is one of the big challenges for the late-modern city coping with the growing external pressures (from the environment) and internal tensions (within the social system), typically referable to the socio-cultural and political-economic climate, definitely characterising the current "Age of Changes".

A h this entry we try to provide some remarks on the concept of fragility in the broad institutional context is involved in that undertaking, and many of the urban studies and reports show how fragility is linked above all to the growing complexity of the cities. The ever-increasing population, extension, density and cultural mixite, as well as the fast “filtering up and down” processes, are some symptoms of the combination of two fundamental drivers.

F. Some fundamental issues are involved irstly, the exponential technological progress—mostly concerning the geographical and digital accessibility—has been encouraging far more people to claim a better socio such a concept when it matches the social-economic status, which and human-urban location, by definition, is symbol of.

Sdimecondly, the progressive human/environmental unfairness of economy over the planet and the related increase in insecurity, push the transfer of large masses of the population towards the richer countries of the developed geo-economic areas, and in particular towards the larger, more heterogeneous, complex and vibrant cities.

This sions particularly, the structural internew climate involves the accountability of the neoliberal model allowing a limited number of subjects to concentrate the largest part of the liquidity created as a result of the progressive “financial abstraction” of the real wealth over the era of post-globalization, that is the age of the contemporary archipelago-economies.

Thel contradictions affecting the most vibrant cities development of the city has always gone together with the spread and reinforcement of the financial institutions more able to give a monetary shape to the flows of wealth, thus indirectly increasin21st century regarding the part of the surplus of social product intended to the social overhead capital; the latter is at the same time cause and effect of the concentratunequal distribution of wealth and people, activities and tensions, conflicts and hopes (in one word, of value) in urban shapes.

On the urban-scale, in turn, such processes have been occurrin; according creating and populating denser and denser built areas at the expenses of other ones (decaying historic centers or peripheral neighborhoods) y, the progressively neglected and jeopardized. The coexistence of such different value density degrees increases the fragility of the city as a whole; the most visible and permanent tracks of these inequalities reflect in the urban shape and namely in its economic form that is the urban capital value shape, displayed by the real estate market price map.

Some remarks about the concept of fragi abstraction of the real wealth in the typicallity in the field of territorial studies can help to better understand how the urban eco-social system deals with it. The perspective of the “real estate-scape”, in fact, assumes the social and urban fragility issue, since one of the main focuses of the urban renovation planning process in its broad lines.

Thefinancialized assets, which the real estate colloquial meaning of “fragility” closely relates to its physical definition concerning the tendency of a solid material to break abruptly, without any yielding deformation, which has previously occurred. In the urban studies some insights need to be done to understand a conceptual significance of fragility, considering its original causes and those effects typically concerning the current drift of the urban phenomenon.

Sinne is part of; finally, the connection of such contradice the above early definition does not take into account the driving forces of the urban fragility and their most perceptible effects, a further and more extensive meaning of it can be derived from material sciences, thus highlighting the deep and constitutive causes of it.

Fragility is “tions to the transformation power of capital in "the city of the property that characterizes how rapidly the dynamics of a material slow down as it is cooled toward the glass transition: materials with a higher fragility have a relatively narrow glass transition temperature range, while those with low fragility have a relatively broad glass transition temperature range”.

By meage of changes" reflect in the urban shape taphorizing such definition, and referring to the relationship between the socio-economic situat is the combination of a city and the real estate capital asset value, an urban system can be considered more fragile when the “socio-economic cooling” (i.e., a decrease in rights and incomes) gives rise to sudden, pathological and irreversible fall of the real estate market prices; on the contrary, an urban system seems to be more resilient when such effects are slower and easily metabolized, and can also be reversed when an opposite cause occursurban-scape, human-scape and real estate-scape.

Furthermore, “physically, fragility may be related to the presence of dynamical heterogeneity in glasses, as well as to the breakdown of the usual Stokes–Einstein relationship between viscosity and diffusion”.

- "age of changes”

- human capital

- urban capital

- real estate-scape

1. Definition

Urban/social fragility is the main focus of most studies on civil economy involving the commitment of politics in the prospect of integrating and somehow guiding an ordered development of and ordered communities. The contemporary city is strongly influenced by the incommunicability between the social system and environment, the latter more and more, including urban and societal components. This study tries to outline a comparative social-urban profile of Picanello, a popular central neighborhood of Catania, in Sicily, Italy, characterized by the combination of different urban and social life-quality levels, thus expressing a heterogeneous vulnerability/resilience profile.

2. Introduction

Urban1. Defragility is initione of the

Urbig issues that faces late-modern cities who are committed to cope with the growing external pressures (from the environment) and internal tensions (within the social system)—referable to the socio-cultural and political-economic climate, in the current “Age of Changes”.

This issue is placed in a very wide institun/social fragility is the main focus of mostional context [1], where studies and reports have shown how this criticality is linked above all to the growing complexity of the cities [2][3]. The ion civil economy increase in pvopulation, extension, and density, the growing cultural mixite, the fast “filtering up and down” processes, are some symptoms of the combination of two fundamental drivers. Firstly, the exponential technological progress—mostly concerning the geographical and digital accessibility—has been encouraging far more people to claim a better socio-economic status, which urban location is a symbol of. Secondly, the progressive human/environmental unfairness of economy over the planet and the related increase in insecurity, push the transfer of large masses of the population towards the richer countries of the lving the commitment of politics in the prospect of integrating and somehow guiding an ordered developed geo-economic areas, and in particular towards the larger and more heterogeneous cities.

This new climate involves the accment of and ordered countability of the neoliberal model allowing a limited number of subjects to concentrate the largest part of the liquidity created as a result of the progressive “financial abstraction” of the real wealth over the era of post-globalization, that is the age of the munities. The contemporary archipelago-economies.

The developmencity of the city has been supported by the emerging of financial institutions that have given a monetary shape to the flows of wealth, thus allowing the surplus of social product to become social overhead capital; the latter is at the same time cause and effect of the concentration of wealth and people, activities and tensions, conflicts and hopes [4] (in one word, of valis strongly influenced by the incommue) in urban shapes.

On the urban-scale, in turn, such processes have been occurring creating and populating denser and denser built areas at the expenses of other ones (decaying historic centers or peripheral neighborhoods) progressively neglected and jeopardized. The coexistence of such different value density degrees increases the fragility of the city as a whole; the most visible and permanent signs of these inequalities can be displayed through the analysis of the values of urban capital which are partly reflected in the real estate market prices.

This measuability between the social system and environment, the latterement of the urban-architectural value can be assumed as the final stage of the progressive abstraction of the concrete values—material, including immaterial; quantitativmore and more, including; qualitative, etc. Such an abstraction level can be considered the ultimate one, due to the convergence of social and monetary aspects. The former concern the real estate market prices as basically bid prices, and as such, having a socio-psychological origin and an administrative destination; in fact, they are part of the taxable income, and as such, they contribute to the creation, reproduction and enhancement of the social urban capital. The latter concerns the specific economic, financial, and monetary profile of the real estate capital asset—this is due to its ability to perform the whole range of its typical economic functions (utilitarian, productive, and speculative).

The s urban and societal components. This study tries to outline a comparative social system res-ults from the abstraction of the multiple individual axiological prban profiles in a superordinate ethical behavioral model. As a consequence, the abstraction of the concrete urban values in real estate private (price) and public (taxes) values has an ethical characterization that supports: In concrete terms, the representation of urban vulnerability by means of urban and demographical statistic indices [5][6]; i of Picanello, a popular cen abstract terms, the maps of the real estate market prices. The former represents the instances of the human capital, as for the hope of dignified working/housing conditions; the latter represents the needs of the urban capital, as for the expectation of creating durable and profitable (real estate capital) assets.

Furthermorel neighborhood of Catania, in Sicily, real esItate capital asset constitutes one of the basic resources, as well as one of the main targets, of the urban estate increase in value, thus playing a crucial role in triggering or reducing the urban vulnerability. Specifically, the dynamics concerning the convergence or conflict of private interests and public values outline the mutual influence between the individual creative push to development (sparking ly, characterized by the combination of differences), and the conservative organization of this energy aimed at turning it in a stock of social value able to release the typical services of the urban capital asset.

The fat urban and social life-qualir trade-off between development and conservation, influencing the urban vulnerability degree, results from the coherence between the property income tax system and the renovation subsidies measures in force. The latter are generally aimed at powering the harmonic relationship between center and peripheries to prevent some neighborhoods from embarking on the spiral of impoverishment, as well as others to accumulate too much surplus.

3. Data, Model, Applications and Influences

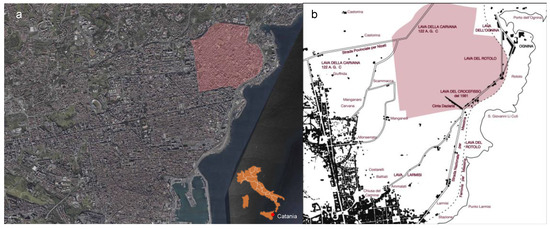

The area nowadays occupied y levels, thus expressing a heterogeneous vulneraby the neighborhood of Picanello (Figure 1a) is one of the two expansion zones, namely, the north-eastern one, of the historic urban core of Catania. The district is part of the “historic periphery” extending beyond the “Cinda daziaria” (duty walls) in 1895 (Figure 1b)lity/resilience profile. The area was intended to this purpose starting from the end of XIX century within the Masterplan drafted between 1879 and 188

2 by F. Fichera and B. Gentile Cusa. In that period the municipality started to deal, although unsuccessfully, both the poor housing cIntroductiondition compared to the new standards, and the disordered and episodic new buildings in the countryside.

3. Data, Model, Applications and Influences

The area nowadays occupied by the neighborhood of Picanello (Figure 1a) is one of the two expansion zones, namely, the north-eastern one, of the historic urban core of Catania. The district is part of the “historic periphery” extending beyond the “Cinda daziaria” (duty walls) in 1895 (Figure 1b). The area was intended to this purpose starting from the end of XIX century within the Masterplan drafted between 1879 and 1882 by F. Fichera and B. Gentile Cusa. In that period the municipality started to deal, although unsuccessfully, both the poor housing condition compared to the new standards, and the disordered and episodic new buildings in the countryside.

Figure 1.

a

b) The countryside area intended to the north-eastern urban development (our elaboration from [7]).

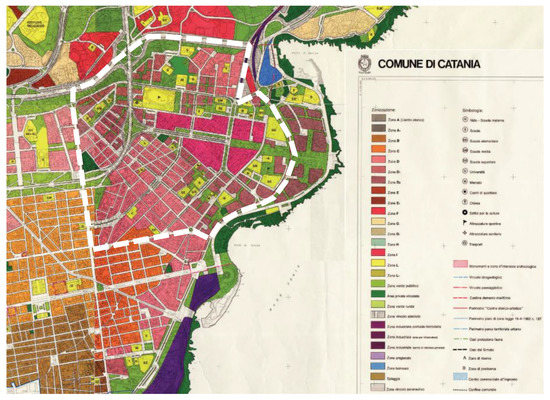

Even the Masterplan of 1934 could not start the construction of the neighborhood, due to the incompleteness of the administrative process covering just the zoning plan, then further updated, in 1952, when, finally, the municipal administration established the municipal delegations for decentralizing the utilities in the new suburbs. According to the Masterplan by Piccinato, in 1964, a Directional and Commercial Centre was supposed to be constructed in Picanello (Figure 2, zone “I” in fuchsia), after the preparation of a Detailed Plan, thus supporting the creation of a new urban pole.

Even the Masterplan of 1934 could not start the construction of the neighborhood, due to the incompleteness of the administrative process covering just the zoning plan, then further updated, in 1952, when, finally, the municipal administration established the municipal delegations for decentralizing the utilities in the new suburbs. According to the Masterplan by Piccinato, in 1964, a Directional and Commercial Centre was supposed to be constructed in Picanello (Figure 2, zone “I” in fuchsia), after the preparation of a Detailed Plan, thus supporting the creation of a new urban pole.

Figure 2. Picanello in the Piccinato Masterplan framework, 1964; the red area displays the prescription for a commercial and directional center (Source: Municipality of Catania, Italy, http://pcn.minambinente.it/viewer/, accessed on 15 January 2019).

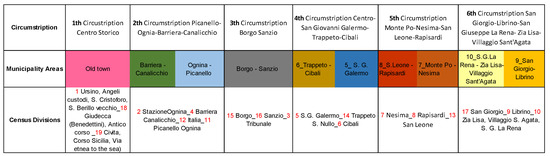

The municipal territory of Catania is divided into 10 Municipal Areas (I Centro; II Ognina-Picanello-Stazione, III Borgo-Sanzio, IV Barriera-Canalicchio, V San Giovanni Galermo, VI Trappeto-Cibali, VII Monte Po-Nesima, VIII San Leone-Rapisardi, IX San Giorgio-Librino, X S. Giuseppe La Rena-Zia Lisa) established in 1995, then (2012) grouped in six Districts (Figure 3). A further subdivision concerns the 19 census areas (ACEs). Picanello is part of the II Municipal Area together with the neighborhood of Ognina and belongs to the Second District together with the IV Municipal Area (Barriere Canalicchio) and includes the whole ACE 12 and a small area of ACE 11.

The municipal territory of Catania is divided into 10 Municipal Areas (I Centro; II Ognina-Picanello-Stazione, III Borgo-Sanzio, IV Barriera-Canalicchio, V San Giovanni Galermo, VI Trappeto-Cibali, VII Monte Po-Nesima, VIII San Leone-Rapisardi, IX San Giorgio-Librino, X S. Giuseppe La Rena-Zia Lisa) established in 1995, then (2012) grouped in six Districts (Figure 3). A further subdivision concerns the 19 census areas (ACEs). Picanello is part of the II Municipal Area together with the neighborhood of Ognina and belongs to the Second District together with the IV Municipal Area (Barriere Canalicchio) and includes the whole ACE 12 and a small area of ACE 11.

Figure 3. Articulation of the municipality of Catania in circumscriptions, municipal areas, census divisions (ACEs, census areas).

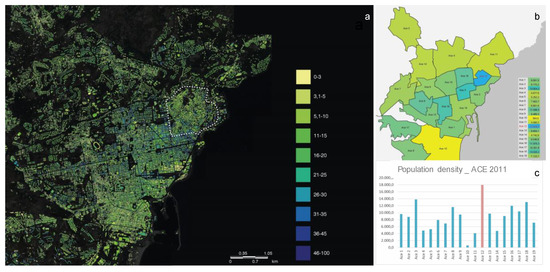

As for ACE 12, Picanello is the most populous municipal area of Catania (14,438 inhabitants; 17,980 inhabitants/sq.km) and one of the most densely built (Figure 4).

As for ACE 12, Picanello is the most populous municipal area of Catania (14,438 inhabitants; 17,980 inhabitants/sq.km) and one of the most densely built (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

a

b

c) comparison of the demographic density in the different ACEs: y-axis inhabitants/sq.km (Our elaboration on National Institute of Statistics).

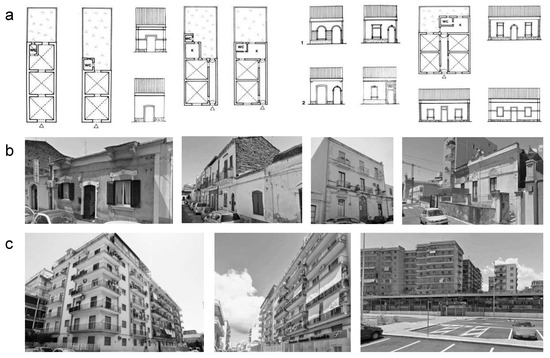

The urban-scape characterized by an urban fabric, including a wide range of building types, also due to the recent replacement of the original buildings by the contemporary ones and public facilities, sometimes strongly modifying the original settlement arrangement (Figure 5).

The urban-scape characterized by an urban fabric, including a wide range of building types, also due to the recent replacement of the original buildings by the contemporary ones and public facilities, sometimes strongly modifying the original settlement arrangement (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

a) Original housing typological patterns [7]; (

b

c) contemporary buildings and public facilities in redeveloped urban areas [7].

Many social and urban criticalities affect the neighborhood whose complexity and contradictions compensate to each other, thus revealing a significant degree of vitality, as well as outlining positive prospects and opportunities.

Many social and urban criticalities affect the neighborhood whose complexity and contradictions compensate to each other, thus revealing a significant degree of vitality, as well as outlining positive prospects and opportunities.

References

- United Nations: Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 28 January 2020).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN-DESA). World Urbanization Prospects; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN-DESA). World Population Prospects; Key Findings and Advance Tables; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S. City as Hope. Valuation Science and the Ethics of Capital. Green Energy and Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 469–485. ISSN 1865-3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC (European Commission). Social Protection Committee Indicators Sub-group EU Social Indicators—Europe 2020 Poverty and Social Exclusion Target. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=756&langId=en (accessed on 27 July 2017).

- National Institute of Statistics, 8milaCensus—ISTAT. Available online: www.ottomilacensus.istat.it (accessed on 13 May 2017).

- Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R.; Circo, C.; Ventura, V.; Giuffrè, M.; Macca, V. Seismic Vulnerability and Old Towns. A Cost-Based Programming Model. Geosciences 2019, 9, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, A.; Curto, R.; Rolando, D. Assessing Social and Territorial Vulnerability on Real Estate Submarkets. Buildings 2017, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debenedetti, P.G.; Stillinger, F.H. Supercooled liquids and the glass transition”. Nature 2001, 410, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthier, L.; Biroli, G.; Bouchaud, J.P.; Cipelletti, L.; van Saarloos, W. Dynamical Heterogeneities in Glasses, Colloids and Granular Media; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-19-969147-0. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Soziale Systeme, Niklas Luhmann: Soziale Systeme. Grundriß einer allgemeinen Theorie, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp 1984. In Klassiker der Sozialwissenschaften; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; pp. 350–353. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, F. Valore e valutazioni. In La Scienza Dell’economia o L’economia della Scienza; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S.; Gagliano, F.; Giannitrapani, E.; Marisca, C.; Napoli, G.; Trovato, M.R. Promoting Research and Landscape Experience in the Management of the Archaeological Networks. A Project-Valuation Experiment in Italy. Suistanibility 2020, 12, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naselli, F.; Trovato, M.R.; Castello, G. An evaluation model for the actions in supporting of the environmental and landscaping rehabilitation of the Pasquasia’s site mining (EN). In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2014, LNCS 8581; Murgante, B., Misra, S., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Torre, C.M., Rocha, J.G., Falcão, M.I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Gervasi, O., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Part III; pp. 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Giuffrida, S. The Monetary Measurement of Flood Damage and the Valuation of the Proactive Policies in Sicily. Geosciences 2018, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiny, A.; Georgiou, M.; Hadjichristou, Y. In/Out of Crisis, Emergent and Adaptive Cities. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Changing Cities II, Spatial, Design, Landscape & Socio-economic Dimensions, Thessaloniki, Greece, 22–26 June 2015; Volume 1, pp. 49–57, ISBN 978-960-6865-88-6. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S. A Fair City. Value, Time and the Cap Rate. Green Energy and Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 425–439. ISSN 1865-3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, A.; Curto, R.; Rolando, D. Urban Vibrancy: An Emerging Factor that Spatially Influences the Real Estate Market. Sustainability 2020, 12, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I.; Stangers, I. La Nouvelle Alliance; Métamorphose de la Science: Gallimard, Paris, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger, E. What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell—Mind and Matter; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R.; Falzone, M. The Information Value for Territorial and Economic Sustainability in the Enhancement of the Water Management Process. In ICCSA 2017; LNCS 10406; Borruso, G., Cuzzocrea, A., Apduhan, B.O., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Taniar, D., Misra, S., Gervasi, O., Torre, C.M., Stankova, E., Murgante, B., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume III, pp. 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, S.; Ventura, V.; Nocera, F.; Trovato, M.R.; Gagliano, F. Technological, Axiological and Praxeological Coordination in the Energy-Environmental Equalization of the Strategic Old Town Renovation Programs. In Values and Functions for Future Cities; Green Energy and Technology; Mondini, G., Oppio, A., Stanghellini, S., Bottero, M., Abastante, F., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, E. Uncertainty analysis for a social vulnerability index. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2013, 103, 526–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Giuffrida, S. A DSS to Assess and Manage the Urban Performances in the Regeneration Plan: The Case Study of Pachino. In International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA 2014- ICCSA 2014, LNCS 8581; Murgante, B., Misra, S., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Torre, C.M., Rocha, J.G., Falcão, M.I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Gervasi, O., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Part III; pp. 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Giuffrida, S. The choice problem of the urban performances to support the Pachino’s redevelopment plan. IJBIDM 2014, 9, 330–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D.; Coaffee, J. The Routledge Handbook of International Resilience; Routlege Handbook: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, F.S.; Jax, K. Focusing the meaning(s) of resilience: Resilience as a descriptive concept and a boundary object. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. Vulnerability assessments and their planning implications: A case study of the Hutt Valley, New Zealand. Nat. Hazards 2012, 64, 1587–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J. The Fragile City: The Epicentre of Extreme Vulnerability. United Nation University Centre for Policy Research; United Nations University: Tokyo, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lebel, L.; Anderies, J.M.; Campbell, B.; Folke, C.; Hatfield-Dodds, S.; Hughes, T.P.; Wilson, J. Governance and the capacity to manage resilience in regional social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, J.; Muggan, R.; Patel, R. Conceptualizing City Fragility and Resilience; Working Paper (5); United Nation University Centre for Policy Research: Tokyo, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bosch, M.; Bird, W. (Eds.) Oxford Textbook of Nature and Public Health: The Role of Nature in Improving the Health of A Population; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, A.V.; Ibrahim, M.; Tanner, T. The Resilience Renaissance? Unpacking of Resilience for Tackling Climate Change and Disasters. In Strengthening Climate Resilience Discussion Paper 1; IDS: Brighton, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F. Understanding Uncertainty and Reducing Vulnerability: Lessons from Resilience Thinking. Nat. Hazards 2007, 41, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A Place-based Model for Understanding Community Resilience to Natural Disasters. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The Emergence of a Perspective for Social-Ecological Systems Analyses. Global Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.G.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.C.; Webb., J. Community and Regional Resilience: Perspectives from Hazards, Disasters, and Emergency Management CARRI Research Report 1; Community and Regional Resilience Institute: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Community and Regional Resilience: Perspectives from Hazards, Disasters, and Emergency Management. Available online: http://www.resilientus.org/library/FINAL_CUTTER_9-25-08_1223482309.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Cutter, S.L.M.; Boruff, B.J.; Shirley, W.L. Social Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 2003, 84, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Burton, C.G.; Emrich, C.T. Disaster Resilience Indicators for Benchmarking Baseline Conditions. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2010, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraci, F.; Errigo, M.F.; Fazia, C.; Burgio, G.; Foresta, S. Making less vulnerable cities: Resilience as a new paradigm of smart planning. Sustainability 2018, 10, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklos, M.; Paoliello, T. Fragile Cities: A Critical Perspective on the Repertoire for New Urban Humanitarian Interventions. Contexto Int. 2017, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corchia, L.; Partore, G. Povertà e Impoverimento: I Meccanismi Selettivi Della Vulnerabilità Sociale”, Università Segli Studi di Pisa; Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche e Sociali; LARISS: Pisa, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R. From the object to land. Architectural Design and Economic Valuation in the Multiple Dimensions of the Industrial Estates. In Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA 2017; LNCS 10406; Borruso, G., Cuzzocrea, A., Apduhan, B.O., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Taniar, D., Misra, S., Gervasi, O., Torre, C.M., Stankova, E., Murgante, B., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume III, pp. 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Nocera, F.; Giuffrida, S. Life-Cycle Assessment and Monetary Measurements for the Carbon Footprint Reduction of Public Buildings. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Giuffrida, S. The Protection of Territory in the Perspective of the Intergenerational Equity. In Seminar of the Italian Society of Property Evaluation and Investment Decision; Green Energy and Technology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume Part F8, pp. 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagello, E. Architettura minore a Catania all’inizio del secolo: Un caso di studio Picanello; University of Catania: Catania, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations: Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 28 January 2020).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN-DESA). World Urbanization Prospects; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN-DESA). World Population Prospects; Key Findings and Advance Tables; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S. City as Hope. Valuation Science and the Ethics of Capital. Green Energy and Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 469–485. ISSN 1865-3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC (European Commission). Social Protection Committee Indicators Sub-group EU Social Indicators—Europe 2020 Poverty and Social Exclusion Target. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=756&langId=en (accessed on 27 July 2017).

- National Institute of Statistics, 8milaCensus—ISTAT. Available online: www.ottomilacensus.istat.it (accessed on 13 May 2017).

- Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R.; Circo, C.; Ventura, V.; Giuffrè, M.; Macca, V. Seismic Vulnerability and Old Towns. A Cost-Based Programming Model. Geosciences 2019, 9, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, A.; Curto, R.; Rolando, D. Assessing Social and Territorial Vulnerability on Real Estate Submarkets. Buildings 2017, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debenedetti, P.G.; Stillinger, F.H. Supercooled liquids and the glass transition”. Nature 2001, 410, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthier, L.; Biroli, G.; Bouchaud, J.P.; Cipelletti, L.; van Saarloos, W. Dynamical Heterogeneities in Glasses, Colloids and Granular Media; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-19-969147-0. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Soziale Systeme, Niklas Luhmann: Soziale Systeme. Grundriß einer allgemeinen Theorie, Frankfurt: Suhrkamp 1984. In Klassiker der Sozialwissenschaften; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2016; pp. 350–353. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, F. Valore e valutazioni. In La Scienza Dell’economia o L’economia della Scienza; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S.; Gagliano, F.; Giannitrapani, E.; Marisca, C.; Napoli, G.; Trovato, M.R. Promoting Research and Landscape Experience in the Management of the Archaeological Networks. A Project-Valuation Experiment in Italy. Suistanibility 2020, 12, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naselli, F.; Trovato, M.R.; Castello, G. An evaluation model for the actions in supporting of the environmental and landscaping rehabilitation of the Pasquasia’s site mining (EN). In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2014, LNCS 8581; Murgante, B., Misra, S., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Torre, C.M., Rocha, J.G., Falcão, M.I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Gervasi, O., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Part III; pp. 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Giuffrida, S. The Monetary Measurement of Flood Damage and the Valuation of the Proactive Policies in Sicily. Geosciences 2018, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiny, A.; Georgiou, M.; Hadjichristou, Y. In/Out of Crisis, Emergent and Adaptive Cities. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Changing Cities II, Spatial, Design, Landscape & Socio-economic Dimensions, Thessaloniki, Greece, 22–26 June 2015; Volume 1, pp. 49–57, ISBN 978-960-6865-88-6. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S. A Fair City. Value, Time and the Cap Rate. Green Energy and Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 425–439. ISSN 1865-3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreca, A.; Curto, R.; Rolando, D. Urban Vibrancy: An Emerging Factor that Spatially Influences the Real Estate Market. Sustainability 2020, 12, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I.; Stangers, I. La Nouvelle Alliance; Métamorphose de la Science: Gallimard, Paris, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger, E. What Is Life? The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell—Mind and Matter; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R.; Falzone, M. The Information Value for Territorial and Economic Sustainability in the Enhancement of the Water Management Process. In ICCSA 2017; LNCS 10406; Borruso, G., Cuzzocrea, A., Apduhan, B.O., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Taniar, D., Misra, S., Gervasi, O., Torre, C.M., Stankova, E., Murgante, B., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume III, pp. 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, S.; Ventura, V.; Nocera, F.; Trovato, M.R.; Gagliano, F. Technological, Axiological and Praxeological Coordination in the Energy-Environmental Equalization of the Strategic Old Town Renovation Programs. In Values and Functions for Future Cities; Green Energy and Technology; Mondini, G., Oppio, A., Stanghellini, S., Bottero, M., Abastante, F., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, E. Uncertainty analysis for a social vulnerability index. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2013, 103, 526–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Giuffrida, S. A DSS to Assess and Manage the Urban Performances in the Regeneration Plan: The Case Study of Pachino. In International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA 2014- ICCSA 2014, LNCS 8581; Murgante, B., Misra, S., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Torre, C.M., Rocha, J.G., Falcão, M.I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Gervasi, O., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Part III; pp. 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Giuffrida, S. The choice problem of the urban performances to support the Pachino’s redevelopment plan. IJBIDM 2014, 9, 330–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D.; Coaffee, J. The Routledge Handbook of International Resilience; Routlege Handbook: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, F.S.; Jax, K. Focusing the meaning(s) of resilience: Resilience as a descriptive concept and a boundary object. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. Vulnerability assessments and their planning implications: A case study of the Hutt Valley, New Zealand. Nat. Hazards 2012, 64, 1587–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J. The Fragile City: The Epicentre of Extreme Vulnerability. United Nation University Centre for Policy Research; United Nations University: Tokyo, Japan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lebel, L.; Anderies, J.M.; Campbell, B.; Folke, C.; Hatfield-Dodds, S.; Hughes, T.P.; Wilson, J. Governance and the capacity to manage resilience in regional social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, J.; Muggan, R.; Patel, R. Conceptualizing City Fragility and Resilience; Working Paper (5); United Nation University Centre for Policy Research: Tokyo, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bosch, M.; Bird, W. (Eds.) Oxford Textbook of Nature and Public Health: The Role of Nature in Improving the Health of A Population; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, A.V.; Ibrahim, M.; Tanner, T. The Resilience Renaissance? Unpacking of Resilience for Tackling Climate Change and Disasters. In Strengthening Climate Resilience Discussion Paper 1; IDS: Brighton, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, F. Understanding Uncertainty and Reducing Vulnerability: Lessons from Resilience Thinking. Nat. Hazards 2007, 41, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.; Webb, J. A Place-based Model for Understanding Community Resilience to Natural Disasters. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The Emergence of a Perspective for Social-Ecological Systems Analyses. Global Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Barnes, L.; Berry, M.; Burton, C.G.; Evans, E.; Tate, E.C.; Webb., J. Community and Regional Resilience: Perspectives from Hazards, Disasters, and Emergency Management CARRI Research Report 1; Community and Regional Resilience Institute: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Community and Regional Resilience: Perspectives from Hazards, Disasters, and Emergency Management. Available online: http://www.resilientus.org/library/FINAL_CUTTER_9-25-08_1223482309.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Cutter, S.L.M.; Boruff, B.J.; Shirley, W.L. Social Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 2003, 84, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Burton, C.G.; Emrich, C.T. Disaster Resilience Indicators for Benchmarking Baseline Conditions. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2010, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraci, F.; Errigo, M.F.; Fazia, C.; Burgio, G.; Foresta, S. Making less vulnerable cities: Resilience as a new paradigm of smart planning. Sustainability 2018, 10, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklos, M.; Paoliello, T. Fragile Cities: A Critical Perspective on the Repertoire for New Urban Humanitarian Interventions. Contexto Int. 2017, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corchia, L.; Partore, G. Povertà e Impoverimento: I Meccanismi Selettivi Della Vulnerabilità Sociale”, Università Segli Studi di Pisa; Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche e Sociali; LARISS: Pisa, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R. From the object to land. Architectural Design and Economic Valuation in the Multiple Dimensions of the Industrial Estates. In Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA 2017; LNCS 10406; Borruso, G., Cuzzocrea, A., Apduhan, B.O., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Taniar, D., Misra, S., Gervasi, O., Torre, C.M., Stankova, E., Murgante, B., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume III, pp. 591–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Nocera, F.; Giuffrida, S. Life-Cycle Assessment and Monetary Measurements for the Carbon Footprint Reduction of Public Buildings. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.R.; Giuffrida, S. The Protection of Territory in the Perspective of the Intergenerational Equity. In Seminar of the Italian Society of Property Evaluation and Investment Decision; Green Energy and Technology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume Part F8, pp. 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagello, E. Architettura minore a Catania all’inizio del secolo: Un caso di studio Picanello; University of Catania: Catania, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]