Cancer is a leading cause of death by disease in children and the second most prevalent of all causes in adults. Testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs) make up 0.5% of pediatric malignancies, 14% of adolescent malignancies, and are the most common of malignancies in young adult men. Although the biology and clinical presentation of adult TGCTs share a significant overlap with those of the pediatric group, molecular evidence suggests that TGCTs in young children likely represent a distinct group compared to older adolescents and adults. The rarity of this cancer among pediatric ages is consistent with our current understanding, and few studies have analyzed and compared the molecular basis in childhood and adult cancers.

1. Introduction

Testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs) are a distinctive set of diseases in oncology practice due to their curability or the mixture of histologies that appears to reflect embryogenesis. TGCTs are the most common solid tumor in young adults, representing 0.4% of new cases from all sites [

1]. In early ages, germ cell tumors represent 3.5% of childhood cancers, occurring in a bimodal distribution with one peak in the first four years of life and a second in adolescence [

2,

3], and TGCTs represents about 20% of all cases [

4]. The incidence rate of testicular germ cell tumors starts to increase in the late teens (10 years old) and reaches its peak in the young adult age group [

5,

6,

7].

TGCTs are classified according to genotype, phenotype, origin cell, and germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS) relationship into three groups. Type I is rare in postpubertal testis and presents as a yolk sac tumor in children less than 6 years old and no precursor cell is identified. Type II is common in postpubertal men in the third and fourth decades of life, with GCNIS as a precursor, which leads to several histologies (see below). Type III usually affects men older than 50 years, and the spermatocitic tumor is a phenotype that is not related to GCNIS. In the current study, we focus on TGCT Types I and II [

8].

TGCTs are organized into two main histological groups, known as seminoma (SE) and non-seminoma germ cell tumors (NSGCTs). Seminoma GCTs are made up of undifferentiated germ cells that can histologically resemble sperm and young oogonia, or even germ cells from developmental strains. NSGCTs are subdivided into several histologies, such as embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac tumors (YSTs), teratoma, choriocarcinoma, and mixed NSGCT, in which different histologies are present in different proportions. In contrast to embryonal carcinoma, which histologically resembles the blastocyst, YST has a complex endodermal morphology with embryonic and extraembryonic endodermal components. Mature teratomas are benign tumors, and are the most differentiated, although they may harbor unique neural differentiation as immature teratomas. Finally, choriocarcinoma has trophoblastic differentiation and characteristically features a high level of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) in the bloodstream [

9].

The clinical presentation of TGCTs usually involves painless swelling of one testis, and is sometimes perceived at a late stage in adults by the partners, and by parents in children. However, it may present with an enlarged tumor or even a palpable abdominal mass when the diagnosis is made at a late stage [

10].

Cisplatin is the most important drug used to treat TGCTs and, in recent decades, has changed the natural history of the disease [

11,

12]. To date, no other drug has outperformed the results of platinum-based combinations; this includes carboplatin, which, in the adult population, has had inferior results [

13,

14]. Different combinations and doses have been used in protocols for adults and children, often to reduce the acute and late toxic effects, without compromising the outcomes in the latter group [

15].

TGCTs have different survival rates according to the age group, with adolescents having a lower rate of event-free survival in a 3 year period (59.9%) compared to children (87.2%) or adults (80.0%) [

3,

16]. Twenty to forty percent of patients with metastatic testicular germ cell tumors relapse after first-line chemotherapy [

11,

12]. Furthermore, approximately 50% of these patients can still be cured, and histology, primary tumor location, response to first-line therapy, tumor marker concentrations, and location of metastases (liver, brain, and bone) have been proven to be important prognostic indicator factors in testicular germ cell tumors, in addition to the dose of chemotherapy [

17].

Different cytogenetic abnormalities are described when comparing the age of presentation [

8]. TGCTs are tumors with a low mutational load, but in their postpubertal presentation, mutations in genes such as

KRAS,

KIT, and

TP53 play a role, in addition to the changes in the number of copies of the

KRAS gene [

8,

18]. Epigenetics has been the focus of attention in TGCTs. SE and NSGCTs have different methylation patterns, and interest in the role of miRNA is growing, particularly miR-371a-3p and miR-375 as potential biomarkers [

18,

19,

20].

2. Etiopathogenesis of TGCT in Child and Adults

Curiously, the pathogenesis of TGCT begins in utero during embryogenesis, when embryonic stem cells give rise to the primordial germ cells in the genital crest present in the midline of the embryo [

21,

22]. Pathogenesis differs in some aspects of differentiation, histogenesis, and genomic instability between adults and children. Primordial germ cells are the most implicated in studies on the tumorigenesis of germ cell tumors, and due to their totipotent nature, TGCTs have a wide range of possible histologies. In Type I TGCTs, prepubertal teratomas, as benign tumors, have limited developmental potential and may arise during the migration of primordial germ cells. However, the chromosomal loss of 1p, 4, and 6q, in addition to 1q, 12, 20q, and 22, are implicated in the development of malignant YSTs, the histology most frequently found in testicular tumors in childhood [

9,

23].

3. Molecular Biology

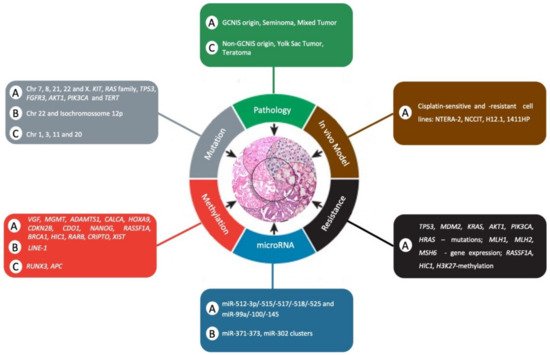

Because TGCTs are a heterogeneous tumor, it is a challenge to study their genetic basis. However, in recent years, efforts have been made to understand the underlying molecular biology () to further improve patient outcomes, particularly for those with chemoresistance and poor risk of disease.

Table 1. Epigenetic-based biomarkers in testicular germ cell tumors in adult and pediatric patients.

| Adult |

Pediatric |

| Biomarker |

Major Findings |

Biomarker |

Major Findings |

| DNA Methylation |

|

|

|

VGF, MGMT, ADAMTS1,CALCA, HOXA9,

CDKN2B, CDO1, and NANOG |

Hypermethylation of MGMT and CALCA promoters associateswith non-seminoma and poor prognosis CALCA associates

with refractory disease. [69] |

RUNX3 |

RUNX3 promoter

hypermethylation was detected in YST in infants (80%). [74] |

| MGMT, RASSF1A, BRCA1, and a transcriptional repressor gene HIC1 |

Non-seminoma showed methylation in MGMT, RASSF1A, and BRCA1 and HIC1. Seminoma showed a near-absence of methylation. [70] |

APC |

APC promoter hypermethylation was detected in YST in infants (70%). [75] |

| RASSF1A, HIC1, MGMT, and RARB |

Hypermethylation of RASSF1A and HIC1 was associated with tumors resistant to cisplatin-based regimens, whereas MGMT and RARB were sensitive. [71] |

Epigenome-wide study |

DMRs were identified in a set of 154 pediatric tumors from gonadal, extragonadal and intracranial locations. [77] |

| XIST |

Unmethylated DNA XIST fragments in seminoma and non-seminoma. [73] |

|

|

| CRIPTO |

Hypomethylation in undifferentiated fetal germ cells, embryonal carcinoma and seminomas. Hypermethylation in differentiated fetal germ cells and the differentiated types of non-seminomas. [72] |

|

|

| LINE-1 |

Strong correlation in LINE-1 methylation levels among affected father-affected son pairs. LINE-1 hypomethylation was associated with the risk of testicular cancer. [76] |

| Genetic abnormalities |

|

|

|

| Isochromosome 12p |

The most commonly observed change in all histological subtypes of TGCTs. [8,34,35] |

Isochromosome 12p |

Less frequent in types I and II. [40,41,42]. |

| Chr 7, 8, 21, 22, and X |

Gains at the arm level target. [38,39] |

Chr 1, 3, 11, 20, and 22 |

Gains in 1q, 3, 11q, 20q, and 22 are common, but still inconsistent. [9,43] |

| RAS family (HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS) |

More common in seminoma when compared to non-seminoma [36,60,61]. |

|

|

| TP53 |

Rarely described in GCTs but, when present, they were associated with a cisplatin-resistant disease, especially in patients with non-seminoma mediastinal [47,48,49,50]. |

|

|

| FGFR3, AKT1, PIK3CA |

Associated with cisplatin-resistant GCTs [54]. |

|

|

| TERT |

TERT promoter mutation is rare [64]. |

|

|

| KIT and KRAS |

KIT mutations in GCTs are associated with RAS/MAPK pathway driver alterations [57]. |

| BRAF |

BRAF mutation was absent [62,63,87,88]. |

| microRNA |

|

|

|

| miR-372 and miR-373 |

miR-372 and miR-373 were particularly abundant in GCT tissue and cell lines. [82] |

miR-371~373 and miR-302 clusters |

miR-371~373 and miR-302 clusters were overexpressed regardless of histological subtype, site (gonadal/extragonadal), or patient age (pediatric/adult) [83]. |

| miR-371~373 and miR-302/367 |

miR-371~373 and miR-302/367 as biomarkers of malignant GCTs were reported [84]. |

|

|

| miR-371a-3p |

Serum miR-371a-3p levels provide both a sensitivity and a specificity greater than 90% and an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.96 [20].

The miR-371a-3p test showed a specificity of 100%, sensitivity of 93%, and AUC of 0.978 [85]. |

|

|

4. In Vitro and In Vivo Models

In recent years, major technological advancements have led to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of TGCTs. However, this progress has had a slight impact on the cancer therapeutic approach, probably due to the limitation of experimental models to predict efficacy in clinical trials. In an effort to offset this limitation, the interest in the development of different TGCT models is increasing.

It remains a challenge for the clinic to investigate the molecular and genetic mechanisms involved in the development of cisplatin resistance in TGCTs, for which the frequency of recurrence is low and the availability of histological samples post-chemotherapy is scarce, because surgical resection of the tumor is the first line of treatment [

99]. In general, cisplatin resistance in TGCTs is commonly studied in primary tumors of patients who may develop them at some point in the future, which is not ideal due to its naive relationship with chemotherapy [

100].

Other strategies to investigate the mechanisms associated with the resistance acquired by tumor cells to cisplatin include the use of preclinical models, in vitro and in vivo, obtained from the cultivation and exposure of TGCT cell lines to incremental doses of the drug, for long periods of time [

101], in addition to the use of animal models that reproduce the phenotypic properties of the human tumor [

102]. Although in vitro cell culture systems have been used extensively for decades, they represent oversimplified models, which are characterized by the absence of heterogeneity and lack of microenvironment components [

103]. Therefore, it is crucial to develop more accurate and clinically relevant mice models that genuinely represent TGCTs in adult and pediatric patients, according to their etiopathogenesis, histopathology, and metastatic progression, and the response of therapy. In this context, patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models have been used as an outstanding alternative [

104,

105]. PDX model development is generated via the transplant of primary tumor fragments or tumor-derived cancer cells from the patient into immunocompromised mice [

106,

107], and has been established in different types of tumors. In TGCTs, PDX models have been developed with a focus on mouse models of resistant disease, which may be established by injecting the cisplatin-resistant clones of TGCT cell lines or by implanting cisplatin-resistant human tumors [

102,

108,

109].

Different models of chemoresistant TGCT cell lines have already been developed and studied for genotypic and phenotypic changes [

99]. NTERA-2 and NCCIT cisplatin-resistant cell lines were injected into immunodeficient mice and disulfiram was used to examine chemosensitization of resistant cell lines. Disulfiram in combination with cisplatin showed synergy for NTERA-2 and NCCIT cisplatin-resistant cells and inhibited the growth of NTERA-2 (cisplatin-resistant) xenografts. High

ALDH1A3 expression and increased

ALDH activity were detected in both refractory cell lines. In addition, the upregulation of the

ALDH isoform

ALDH1A3 was confirmed in 216 patient samples with all histological subtypes of testicular tumors. These results suggest

ALDH1A3 as a novel therapeutic treatment in TGCTs, and disulfiram represents a feasible treatment option for refractory TGCTs [

109].

Our group developed an in vitro model of cisplatin resistance to identify new potential therapies for TGCT-resistant patients (data not published). We established a CDDP-resistance model using the NTERA-2 cell line (NTERA-2R), which was treated for approximately eight months with incremental doses of CDDP. We then performed a phenotypical characterization and NTERA-2R exhibited a significant increase in cell proliferation capacity, augmented clonogenic survival, and higher migration ability, suggesting an aggressive phenotype. To elucidate the molecular changes associated with CDDP-resistance, we analyzed the expression of genes related to damage and repair mechanisms. Compared to the parental cell line, NTERA-2R showed several differentially expressed genes related to DNA repair and cell cycle regulation. These results support the idea that the main change in NTERA-2R is possibly an increased DNA repair capacity and specific changes in cell cycle control, which may trigger apoptosis evasion and allow cells to proliferate, even in the presence of CDDP adducts.

Changes in the cell cycle (increase in G1 and decrease in the S phase), increase in the number of acquired mutations (mainly in the

ATRX gene), changes in the gene expression pattern, and chromosomal variation (gain of 12p, 1, 17, 20, and 21 loss of X) were also observed in the resistant NCCIT strain [

100].

To investigate cisplatin-resistance genetic basis in TGCT, Piulats et al. implanted a collection of matched cisplatin-sensitive and -resistant non-seminoma tumors in nude mice and compared the genomic hybridization (CGH). Comparative CGH analyses showed a gain at the 9q32-q33.1 region, and the presence of this chromosomal rearrangement was correlated with poorer overall survival (OS) in metastatic germ cell tumors. Moreover,

POLE3 and

AKNA genes were deregulated in resistant tumors harboring the 9q32-q33.1 gain. Therefore, the cisplatin-refractory orthoxenografts of TGCTs are potent models to test the efficiency of drugs, and identify prognosis markers and gene alterations [

102].

An immunohistochemical study investigated xenograft models and NSGCT samples with a focus on OCT4-negative cells with undifferentiated EC morphology and their association with chemotherapy resistance [

108]. Subcutaneous xenograft tumors of the NSGCT cell lines H12.1 (cisplatin-sensitive) and 1411HP (cisplatin-resistant) were established in athymic nude mice. The cisplatin-sensitive cell line H12.1 leads to xenografts in which EC structures are mainly composed of OCT4-positive cells, whereas xenografts from the resistant cell line 1411HP exclusively comprise OCT4-negative EC areas, suggesting that the growth of NSGCTs in patients with cisplatin-refractory disease may be determined by OCT4-negative EC cells [

108]. In addition to this data, a mouse TGCT model featuring germ cell-specific Kras activation and Pten inactivation was developed as a representative model of malignant TGCTs in men. The resulting mice developed malignant, metastatic TGCTs composed of teratomas and embryonal carcinomas, the latter of which exhibited stem cell characteristics, including expression of the pluripotency factor OCT4 [

110].

The need for new therapeutic options for patients with natural or acquired resistance to cisplatin has led to the investigation of the activity of different compounds (kinase inhibitors directed at mTOR, EGFR, HER2, VEGFR, and IGF-1R), in sensitive (H12.1 and GCT72), and resistant (H12.1RA, H12.1D, 1411HP, and 1777NRpmet) cell lines of TGCT. Research has shown that these compounds have potential activity when used alone, but not when in combination with cisplatin [

111].

Despite these recent advances in the use of mouse models to study TGCTs, such models must be developed for pediatric patients, and new molecular studies must be performed to provide powerful experimental tools to prioritize new therapeutic approaches for future clinical trials. summarizes the comparison of clinical and molecular differences between adult and pediatric patients with TGCTs as hallmarks of cancer.

Figure 2. Comparison of clinical and molecular differences between adult and pediatric patients with TGCTs as a hallmark of cancer. The letter “A” represents adults, “C” represents child, and “B” represents both adult and child. Adapted from Hanahan and Weinberg [

112].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers13102349