It has become clear that microRNAs, a class of short single-stranded RNA molecules that regulate gene expression at the transcriptional or post-translational level, play a crucial role in coordinating plant-pathogen interactions. Specifically, miRNAs have been shown to be involved in the regulation of phytohormone signals, reactive oxygen species, and NBS-LRR gene expression, thereby modulating the arms race between hosts and pathogens. Adding another level of complexity, it has recently been shown that specific lncRNAs (ceRNAs) can act as decoys that interact with and modulate the activity of miRNAs.

- miRNA

- plant

- pathogen

- interaction

- arms race

1. Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNA molecules of 20–24 nts in length which are encoded by MIRNA genes and can regulate complex biological processes in plants. MIRNA genes are usually transcribed by RNA polymerase II (pol II), and the initial product is a large primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) with a 5′-cap structure (7MGpppG) and a polyadenylated tail [1]. The pri-miRNA is processed to yield a precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA) with a self-complementary stem-loop. The pre-miRNA is diced to generate a miRNA/miRNA* duplex of approximately 22 nucleotides in length, which undergoes a methylation. The RNA duplex is then quickly exported into the cytoplasm where the mature miRNA interacts with Argonaute (AGO) protein to form the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) [2]. Alternatively, the mature miRNA might form a complex with AGO protein in the nucleus that is subsequently exported into the cytoplasm in a CRM1(EXPO1)/NES-dependent manner [3]. The N termini of all plant AGO1s contain a nuclear-localization (NLS) and nuclear-export signal (NES), which enables AGO1 nucleo-cytosolic shuttling [3]. Regardless of where in the cell the miRNA is loaded into the RISC, eventually, it binds by base pairing to a target RNA in cytoplasm [4,5,6].

The genetic regulation of miRNAs is one of the key mechanisms of plant response against biotic and abiotic stresses [7]. In general, most plant miRNAs guide AGO proteins to recognize their target RNAs by perfect or near-perfect sequence match and guide endonucleolytic target RNA cleavage, resulting in rapid degradation of target mRNA. miRNAs can also guide the cleavage of protein-coding and non-coding transcripts, such as those derived from TAS loci, to induce production of phased secondary small interfering RNAs (phasiRNAs), which in turn can lead to cleavage of complementary mRNAs [8,9,10]. miRNAs have also been shown to inhibit translation of their target mRNAs, thus limiting protein production [11,12,13]. Furthermore, miRNAs can regulate target gene expression by histone modification and DNA methylation [14,15]. For instance, 24-nt long miRNAs, called lmiRNAs, have been found to direct DNA methylation at their source and also function in trans on target genes to regulate gene expression in rice [16].

Plant diseases caused by various pathogens, such as bacteria, fungi, oomycetes, and viruses incur severe damage to forests and crop losses every year. Unraveling the interplay between miRNAs and their targets in disease resistance has been challenging. However, thanks to advances in high-throughput technologies, a growing number of miRNAs responding to biological stresses have been discovered and information regarding their expression levels, targets, and mode of action in the response to viruses, fungi, and bacteria in diverse plants is becoming clear. As a result, numerous regulatory circuits that place miRNAs in the process of plant defense against different pathogens have been identified in the past few years.

2. Role of Plant miRNAs in Disease Resistance

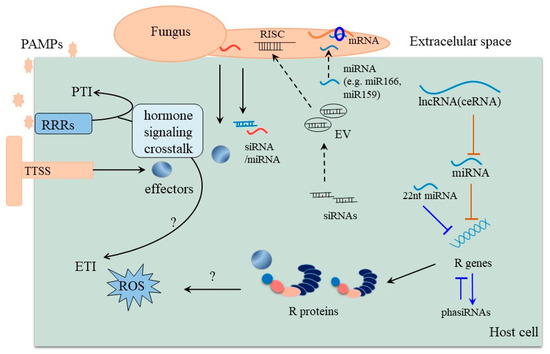

Plants respond to pathogen invasion via two different types of immune responses, the pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI) [17,18]. Pathogens in turn can respond with a diverse array of virulence factors to suppress host defenses. Plant intracellular disease resistance (R) protein encoded by R genes can recognize these virulence effectors, often triggering a hypersensitive cell death response. Increasing evidence demonstrates that miRNAs are involved in PTI and ETI. In particular, miRNAs are involved in the regulation of a variety of defense signals and pathways, including NBS-LRR gene expression, hormone signals, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and cross-kingdom gene silencing, which contributes to the ongoing arms race between hosts and pathogens. Interestingly, miRNAs can also be decoyed by some specific ncRNAs (ceRNAs), thereby attenuating the repressive effect of miRNAs on their authentic targets.

3. Role of Small RNAs including miRNAs in the Arms Race between Host and Pathogen

Plants will inevitably encounter a variety of biotic stresses during growth. A consequence of the constant exposure is an ongoing arms race in which plants constantly try to evolve mechanisms to counter potentially harmful microorganisms while the latter tries to overcome these protective measures. At the core of this ongoing battle are so-called effector proteins that are produced by pathogens to subvert host immune responses and facilitate disease development [41]. Some pathogen effectors act by inhibiting the biogenesis of small RNAs, thereby suppressing RNA silencing in plants [42]. Phytophthora Suppressor of RNA Silencing 1 (PSR1) can bind to the nuclear protein PSR1-Interacting Protein 1 (PINP1), which affects the localization of the Dicer-like 1 protein complex, leading to impaired miRNA-processing [41]. Recent studies have found that some pathogens can deploy cross-kingdom small-RNA effectors that attenuate host immunity and facilitate infection. Interestingly, host plants sometimes respond to attack by exporting specific sRNAs including miRNAs to induce cross-kingdom gene silencing in pathogenic fungi, thereby conferring disease resistance (Figure 2) [43,44]. The disease-related cross-kingdom sRNAs known so far acting in different plants and pathogens are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of disease-related cross-kingdom sRNAs acting in different plants and pathogens.

|

Plant sRNA (Pathogen sRNA) |

Targets of Plant sRNA in Pathogen |

Plant |

Pathogen |

Referencs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

miR166 |

Arabidopsis thaliana |

Botrytis cinerea |

[46] |

|

|

miR1023 |

FGSG_03101 |

Wheat (Triticum aestivum) |

Fusarium graminearum |

[50] |

|

miR166 |

Clp-1 |

Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) |

Verticillium dahliae |

[43] |

|

miR159 |

HiC-15 |

Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) |

Verticillium dahliae |

[43] |

|

(Pst-milR1) |

Wheat (Triticum aestivum) |

Puccinia striiformis f. sp.tritici (Pst) |

[51] |

|

|

TAS1c-siR483 |

BC1G_10728; BC1G_10508 |

Arabidopsis thaliana |

Botrytis cinerea |

[46] |

|

TAS2-siR453 |

BC1G_08464 |

Arabidopsis thaliana |

Botrytis cinerea |

[46] |

|

IGN-siR1 |

Arabidopsis thaliana |

Botrytis cinerea |

[46] |

|

|

Bc-DCL-targeting sRNAs |

Bc-DCL |

Arabidopsis thaliana |

Botrytis cinerea |

[52] |

|

siRNA-1310 |

Phyca_554980 |

Arabidopsis thaliana |

Phytophthora |

[45] |

|

(Bc-siR3.1) |

Arabidopsis thaliana; Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) |

Botrytis cinerea |

[47] |

|

|

(Bc-siR3.2) |

Arabidopsis thaliana; Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) |

Botrytis cinerea |

[47] |

|

|

(Bc-siR5) |

Arabidopsis thaliana; Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) |

Botrytis cinerea |

[47] |

For example, infection with Phytophthora induces the production of a large number of secondary siRNAs from specific transcripts in Arabidopsis. These siRNAs enter the Phytophthora via extracellular vesicles and silence specific Phytophthora target genes to confer resistance [45]. Similarly, in response to infection with V. dahliae, Arabidopsis miR166 was exported into the fungal hyphae to suppress pathogenicity [46]. miR166 and miR159 were also induced in cotton and exported to the pathogenic hyphae to inhibit virulence gene expression in response to V. dahliae infection [43]. Two V. dahliae genes Clp-1 and HiC-15, which are essential for fungal virulence, are targeted by miR166 and miR159, respectively. This cross-kingdom inhibition of virulence gene in pathogenic fungi confers cotton disease resistance [43]. Potentially even more interesting is the interaction between B. cinerea and Arabidopsis. In this case, B. cinerea was reported to transfer some small RNAs (Bc-sRNAs) into host plant cells and hijack the host RNA interference (RNAi) machinery by binding to Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE 1 (AGO1) and selectively silencing host disease resistance genes to suppress host immunity [47]. Conversely, Arabidopsis secreted exosome-like extracellular vesicles to deliver sRNAs including miR166 into B. cinerea [46], making this a prime example of an arms race in which both sides, plants and pathogens, employ small RNAs.

In plants, an active immune response usually has deleterious effects on plant growth, hence maintaining the balance between yield and disease resistance has become a major challenge in plant breeding [48,49]. miRNA-mediated R gene turnover has been proven to be a protective mechanism for plants to prevent autoimmunity in the absence of pathogens. It has recently been demonstrated that miR1885 is involved in balancing the tradeoff between growth and defense in Brassica through distinct modes of action. miR1885-dependent silencing of the photosynthesis-related gene BraCP24 was induced upon Turnip mosaic virus (TuMV) infection, speeding up floral transition, whereas miR1885-mediated turnover of the R gene BraTNLI was overcome by TuMV-induced BraTNLI expression [48]. The precise and dynamic modulation of the interplay between growth, immunity, and pathogen infection reflects the sophisticated arms race between plants and pathogens.

4. Interaction between Disease Related miRNA and lncRNA

An interesting feature of miRNAs is that their abundance is not only regulated at the level of transcription and processing of the miRNA precursor but though other RNA molecules that directly interact with and inhibit miRNAs though (partial) sequence complementarity. Interestingly, it has recently been shown that some miRNAs could potentially be decoyed by some specific endogenous long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) (Figure 2). LncRNAs are a class of RNA transcripts (>200 nt) lacking protein-coding potential and have lower sequence conservation compared with miRNAs. Such lncRNAs with miRNA complementarity could act as endogenous target mimics (eTMs), also referred to as ceRNAs (competing endogenous RNAs), to decoy miRNAs by competing for their targets, thereby attenuating the repressive effect of miRNAs on their targets [53,54,55,56,57,58]. Numerous lncRNAs have been predicted as miRNA decoys to regulate plant immunity through transcriptome sequencing and co-expression analysis in maize, wheat, melon, and tomato [59,60,61,62]. While only a few lncRNAs-miRNAs interactions were verified by transgenic methods in tomato. lncRNA23468 functions as a ceRNA that modulates NBS-LRR genes by decoying miR482b during Phytophthora infestans infection in tomato, thus establishing a lncRNA23468-miR482b-NBS-LRR network of tomato resistance to P. infestans [63]. Similarly, miR159 was decoyed by lncRNA42705 and lncRNA08711 resulting in increasing expression level of its target MYBs [61], and lncRNA39026 could function as ceRNA of miR168a to modulate PR genes in tomato for enhanced resistance to P. infestans [64]. LncRNAs could act as miRNA decoys in response to pathogen infection, which adds complexity at the level of RNA interaction regulation in the plant. Taken together, while the study of lncRNAs in modulating plant-pathogen interactions is still at its beginning, this particular line of research holds a lot of promise for the future.

5. Regulatory Modes of Disease-Related miRNAs in Plants

Plants have evolved diverse molecular mechanisms that enable them to respond to a wide range of pathogens. Disease-related miRNAs that are involved in a variety of defense signals and pathways and that can affect plant immunity either positively or negatively, are summarized in Supplementary Table S1 [5,20,21,22,23,27,31,34,35,36,37,38,39,43,45,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87]. The main targets of these miRNAs are NBS-LRR genes, hormone receptors, transcription factors, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) family genes. Of these, miRNAs targeting hormone receptors regulate defense response mainly in a positive manner, whereas miRNAs targeting NBS-LRR transcripts principally play a negative role in plant immunity (Supplementary Table S1).

Although many miRNAs are conserved in plants, their expression levels, targets, and regulation patterns change to varying degrees in the defense process of plants to viruses, fungi, and bacteria among different plant species. For example, miR398b was reported to positively regulate the immunity response of rice against M. oryzae [36], whereas miR398b plays a negative role in the defense response of Arabidopsis against DC3000 bacteria [67,78], indicating that miR398b may be involved in immunity responses with an inverse regulatory mode of action for bacterial and fungal pathogen species. This may be related to an integrative regulatory module mediated by miR398b, which targets genes encoding superoxide dismutase (SOD) family members CCSD, CSD, and SODX [36,78]. Antagonistic regulation of one miRNA was also observed in poplar where miR472a overexpression lines showed higher susceptibility to flg22 and hemibiotroph Colletotrichum gloeosporioides but exhibited enhanced resistance to the necrotrophic fungus Cytospora chrysosperma [23]. Similarly, tomato miR482, whose targets certain NBS-LRR genes was repressed in the defense reaction to bacteria and viruses [5], whereas poplar miR164 and miR1448, which also target NBS-LRR genes, increased during canker pathogen infection [72]. Thus, different pathogen species may affect miRNA regulation differently. It may be related to the effector types secreted by different pathogens, the specific recognition of different pathogen effectors by plant R genes which can be regulated by diverse miRNAs plays a key role in the immune response in plants. Apart from that, this difference may be caused by the stress strength of the pathogen infection, tomato was sampled at 4 h post-inoculation whereas poplar was sampled at more than 72 h (3, 5, and 7 days) post-inoculation in above research [5,72], indicating miRNAs expression might display at the dynamic expression changes of immunity response. Pathological development is a dynamic process. Therefore, research conclusions are sometimes subject to different sampling experiment designs for the inoculation stages.

Plants developed a suite of defensive mechanisms to cope with environmental stresses. Accordingly, miRNAs grouped in the same family might have evolved more members in different species or varieties and some plants have also evolved some species-specific miRNAs coordinating the complex regulatory mechanisms in plants [88]. miR482/2118 superfamily is one of the conserved disease-related miRNA families in cotton, Populus, and Solanaceae, but this family does not exist in Arabidopsis [89,90,91]. Several newly expanded MIR482/2118d loci have mutated to produce different miR482/2118 variants with altered target-gene specificity in tetraploid cotton compared with their extant diploid progenitors [91]. Previous research showed that the resistance gene R3a in potato was cleaved by miR482 family and produced phasiRNA [86]. In contrast, in tomato, the R3a homolog I2 was targeted by miR6024 even though miR482 also exists [86]. Evolutionary analysis of I2 homologs revealed a considerable divergence between potato and tomato I2 locus, which may account for the regulation of I2 homologs by two miRNAs [86]. Hence, evolution of resistance gene families may attribute to the regulation mediated by different miRNAs.

6. The Applications of miRNAs in Molecular Breeding for Disease Resistance

The elucidation of miRNA function in the regulation of target genes has led to the development and application of several miRNA-based approaches for plant breeding. This is also the case in plant disease-resistant breeding, where understanding the role of specific miRNAs in plant-pathogen interaction systems has already led to several successful applications. One straightforward method is to modulate agronomic traits by constitutively overexpressing a specific miRNA. For example, overexpression of rice-specific miRNA osa-miR7695 increases resistance to infection by the fungal pathogen M. oryzae [68]. On the other hand, overexpressing a miRNA-resistant form of the target that escapes the cleavage by its miRNA or using an artificial miRNA–target mimic that inhibits the activity of a given miRNA might also be effective strategies to attenuate the effect of miRNAs that function as negative regulators of the traits of interest [53]. Recently, artificial miRNAs (amiRNAs) have become increasingly popular in plant disease resistance breeding. In particular when it comes to battling the effects of the virus, which are mostly mixed infections and mutate rapidly, on the productivity of crops and trees. Intriguingly, amiRNAs to a certain extent allow mismatches in their target region. Artificial miRNAs designed to target relatively conserved regions of a virus can effectively inhibit most virus strains and confer resistance even after the virus has started to accumulate mutations [92,93], which is of great significance for the cultivation of durable and broad-spectrum antiviral varieties. For instance, transgenic tomato plants expressing an artificial miRNA targeting the ATP/GTP binding domain of AC1 gene of tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus (ToLCNDV) could effectively resist ToLCNDV infection [94]. Artificial miRNAs were also successfully used to effectively inhibit the infection of tobacco plants by Potato virus Y (PVYN) and Tabacco etch virus (TEV) [92].

While the transgenic approaches obviously work, such plants might be difficult to market. Hence other technologies are needed. The latest developments in genome editing tools have paved the way for targeted mutagenesis, opening new horizons for precise genome engineering. For example, CRISPR/Cas9 is an entrancing and versatile tool for plant genome editing [95], as it enables genetic improvement by editing endogenous genes. In the best scenario, such improvements are made using DNA-free delivery of CRISPR/Cas9, thus completely avoiding the formation of transgenic plants [95,96]. But even if transgenes are introduced in the plant genome to facilitate efficient mutagenizes, these transgenes are usually in trans to the targeted locus and can be removed by genetic crossings, thus reducing safety issues that are a major public concern when it comes to traditional transgenic methods. One way by which CRISPR/Cas9 can be employed is to directly disrupt disease-causing genes and develop disease-resistant crops. For example, targeted knockout of the ethylene-responsive gene OsERF922 using CRISPR/Cas9 resulted in increased resistance against Magnaporthe oryzae in rice [97].

Likewise, CRISPR/Cas9 could be employed to mutate MIRNA genes to enable the plant to generate novel miRNAs that, for example, target pathogen effectors normally not recognized by the plant. Alternatively, a strategy could also be employed to introduce silent mutations in transcripts that are targeted by small RNAs originating from pathogens (see above). However, while such an approach seems feasible in principle, it has not been reported in plants so far. In contrast, several cases of successful CRISPR/Cas-mediated engineering of cis-regulatory elements via genome editing in plants have been reported. For example, the deletion of a regulatory fragment containing a transcription-activator-like effector (TALe)-binding element (EBE) through CRISPR/Cas9 in the promoter of SWEET11 improved rice disease resistance [98,99]. Furthermore, editing of effector-binding elements (EBEs) in the promoters of SWEET genes resulted in rice lines with bacterial blight resistance [98,99]. In principle, mutations might also be induced in cis-regulatory regions of disease-related MIRNAs to regulate their expression. However, to the best of our knowledge, such experiments have not yet been reported. These examples clearly demonstrate the potential of CRISPR/Cas9 for engineering resistance traits in crops. The challenges that remain are mainly to improve the efficiency and fidelity of CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis in a wide range of plant materials.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22062913