The search for an effective drug to treat oncological diseases, which have become the main scourge of mankind, has generated a lot of methods for studying this affliction. It has also become a serious challenge for scientists and clinicians who have needed to invent new ways of overcoming the problems encountered during treatments, and have also made important discoveries pertaining to fundamental issues relating to the emergence and development of malignant neoplasms. Understanding the basics of the human immune system interactions with tumor cells has enabled new cancer immunotherapy strategies. Understanding the ways in which present therapies work, their advantages and disadvantages and how we can improve therapies is essential for developing next generation, or new treatments for cancer.

- immunotherapy

- cancer

- immune checkpoint inhibitors

- cytokine therapy

- vaccines

- oncolytic viruses

- CAR T-cell therapy

1. Introduction

In 1909, Paul Ehrlich predicted that the immune system normally prevents the formation of carcinomas from various origins. The first demonstration of a specific immune system response was made almost half a century later in 1953 by Gross [1]. Unfortunately, malignant neoplasms may evade such immune responses. It is known that malignant neoplasms downregulate the molecules of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-I, thereby preventing recognition of tumor cells by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs). However, the immune system, in turn, is able to destroy cells that do not express, or insufficiently express, MHC-I molecules on their surface using natural killer cells (NK-cells) [2]. However, tumor cells can also protect themselves from NK-cell lysis by expressing non-classic human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-G molecules on their surface [3]. Additionally, tumor cells can trigger angiogenesis [4], and can also recruit T-regulatory cells with immunosuppressive properties via chemical signals [3]. Thus, malignant neoplasms may evade the host immune response, creating a tumor microenvironment. Gavin Dunn and Robert Schreiber developed the concept of “cancer immunoediting” in three phases. In the first phase, tumor cells are eliminated by cells of the immune system (NK cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocytes) [5]. In the second phase, there is an equilibrium between tumor cells and cells of the immune system. In the third phase, the immune system is unable to cope with the tumor, which has an impressive immunosuppressive effect; therefore, the phase ends with the appearance of a clinically detectable tumor [5]. Nowadays, the priority task is to create an effective immunotherapeutic method with minimal toxicity to overcome the immunosuppressive activity of the tumor cells and enhance targeted elimination of the tumor by the immune system host cells. Most immunotherapeutic methods, for example monoclonal antibodies, target specific antigens on the tumor cell surface to produce effective and accurate actions, and some methods, like dendritic vaccines, use these antigens to enhance the immunostimulating and immunomodulatory immune system activity. There are some types of antigens located on the surface of tumor cells that can induce a specific immune response. Such antigens were shown by Richmond Prehn and Joan Mine in their murine experiments in 1957 [6]. Subsequently, the so-called tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) were discovered. These include molecules that are expressed on the surface of cells in a prevailing amount, or in a state different from that observed in normal cells. Other tumor biomarkers include tumor-specific antigens (TSAs), which are fragments of novel peptides that are presented by MHC-I at the cell surface. The first TSAs were discovered in 1991 in human melanoma cells, which are encoded by the melanoma-associated antigen (MAGE) gene family [7]. There are also neoantigens that are the result of somatic mutations and are specific to each patient, thus differing from wild-type antigens. These antigens are used in immunotherapy methods like a target for the recognition and subsequent elimination of tumor cells. Therefore, cancer immunotherapy aims to use the memory and specificity of the immune system to effectively eliminate malignant neoplasms for long periods of time and with minimal toxicity. Immunotherapy methods are also aimed at stimulating the body’s own immune system in order to fight off the tumor. Immunotherapeutic methods presently include cytokine therapy, monoclonal antibodies, oncolytic viruses, prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

2. Cancer Immunity

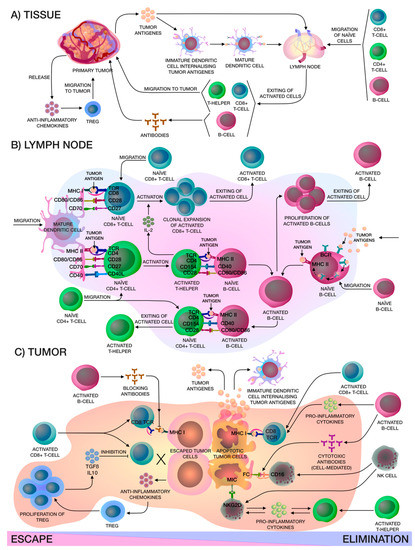

The relationship between a tumor and the human immune system is dynamic and complex. The process of detecting and eliminating tumor cells in the body is a stepwise process, and both cellular and humoral immunity are involved (Figure 1). Formation of tumor cells in the human body is problematic as both have multifactorial profiles, but the body’s immune cells constantly patrol its surroundings and when neoantigens created as a result of oncogenesis are present, dendritic cells (DCs) take them up by phagocytosis or endocytosis. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and other factors direct the immune response, whereby DCs migrate to the lymph nodes to present the captured antigens on MHC-I and MHC-II molecules to T-lymphocytes. Then, there are priming, activation and differentiation of the T-cell response, representing the ratio of T-effector and T-regulatory cells (Treg). Thereafter, T-helpers (Th) 1 produce interleukin (IL)-2 for the clonal expansion of activated cytotoxic T-cells, which then penetrate into the tumor bed, and recognize and bind to cancer cells via the T-cell receptor (TCR) and MHC-I [8].

Figure 1. (A) Localized in the adjacent tumor tissue, the immature CD14+ dendritic cells (DCs) internalize the captured tumor antigen, become mature CD14+ DCs and migrate to the lymph node for presentation to naïve lymphocytes, in particular CD8+ T-cells, CD4+ T-cells and CD19+ B-cells, which are in constant recirculation. After that, activated lymphocytes exit from the lymph node, activated CD19+ B-cells produce corresponding antibodies and activated CD4+ T-helpers and CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs) migrate to the tumor niche. At the same time, the primary tumor releases chemokines that attract FOXP3hi Tregs. (B) In the lymph node, mature CD14+ DCs present tumor antigens to naïve lymphocytes, activated CD4+ T-helpers release interleukin (IL)-2 for clonal expansion of activated CD8+ CTLs and help naïve B-cells on the border of the B-cell zone of the lymph node. In addition, naïve B-cells may capture tumor antigens from the lymph and, after internalizing, activated B-cells proliferate and, furthermore, they can present tumor antigens to naïve CD4+ T-cells. All in all, activated lymphocytes leave the lymph node. (C) There are two mechanisms that occur in the tumor niche: escape or elimination. Elimination of the tumor, in the main, occurs due to activated CD8+ CTLs and CD56+ natural killer (NK)-cells. Activated CD19+ B-cells only help activated CD8+ CTLs and CD56+ NK-cells by releasing interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and IL-12, which enhance the cytotoxic effects, and also produce cytotoxic antibodies that cause a cell-mediated immune response. Activated CD4+ T-helpers and CD56+ NK cells release pro-inflammatory cytokines like IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor alpha-α (TNF-α), that enhance each other. Apoptotic tumor cells release antigens that stimulate immune cells. On the other hand, primary tumors can inhibit effector immune cells by releasing soluble antigens and anti-inflammatory chemokines that attract FOXP3hi Tregs, thereby creating a tumor microenvironment. Moreover, antibodies produced by activated CD19+ B-cells may block access to tumor cell for activated CD8+ CTLs.

3. Cytokine Therapy

Cytokines are polypeptides or glycoproteins produced by activated cells of the hematopoietic or immune system, which mediate growth and differentiation signals, as well as inflammatory or anti-inflammatory signals to other cells. Cytokine therapy, one of the most promising methods of immunotherapy, was formed due to the presence of proapoptotic or antiproliferative activity in cytokines, as well as the possible stimulation of cytotoxic activity in immune cells. The antitumor activity of cytokines was first described by Ion Gresser and Chantal Bourali using the example of recombinant murine IFN-α in 1970 [13]. Scientists carried out daily intraperitoneal injections of IFN-α into BALB/c, C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice, inoculated intraperitoneally with several thousand Ehrlich ascites (EA), RC19, EL4, L1210, and E♂G2 tumor cells. The most pronounced antitumor effects were observed in the BALB/c line inoculated with EA cells. Thereafter, several fundamental conclusions were made: treatment of mice with IFN-α and without EA inoculation was ineffective; subcutaneous administration was less effective than intraperitoneal administration; the increased survival of mice with effective treatment was directly related to effective tumor inhibition and inversely proportional to the amount of EA inoculated; phagocytosis of tumor cells by macrophages was observed only on smears obtained from abdominal cavities treated with interferon; mice that survived inoculation of EA cells, which were injected with interferon, exhibited increased resistance to repeated inoculation of EA cells [13]. In subsequent years, this discovery gave rise to a large number of preclinical and clinical trials using recombinant cytokines for antitumor immunotherapy. However, the high expectations of scientists were not justified, due to the limitations that arose in clinical trials, such as the short half-life of most cytokines, which leads to low therapeutic effects which necessitated use of higher drug doses, which led to high levels of toxicity with concomitant side effects [8]. Only two cytokines, IL-2 and IFN-α, have been approved so far by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and have shown only moderate efficacy in studies [14]. These cytokines have demonstrated for the first time that immunotherapy can affect tumor development within the body and give a definite antitumor immune response, despite high toxicity levels [14,15,16].

Recombinant IFN-α is used in high doses for the treatment of melanoma, leukemia and Kaposi’s sarcoma [17,18,19]. The main side effects observed with IFN-α therapy have been fever, chills, flu-like symptoms, and more serious symptoms including hepatic dysfunction, thyroid disorders, depression and anorexia. IntronA is the most famous drug based on recombinant IFN-α, which was manufactured by MSD Pharmaceuticals until 2019. Various modifications of IFN-α appeared to be aimed at increasing the half-life, as well as increasing the immunostimulating properties, thus minimizing its toxicity [20,21]. However, the emergence of new, safer and more effective methods of immunotherapy has reduced the number of clinical trials with this protein.

IL-2 is a key cytokine that stimulates the proliferation of NK cells and T-lymphocytes; therefore, it is actively used both for adoptive cell therapy using T-lymphocytes and for direct administration to patients [14]. Recombinant IL-2 is the main active ingredient in Proleukin. This drug is approved for the treatment of metastatic melanoma and metastatic kidney cancer [22,23]. However, it also causes frequent side effects of grade 3 and 4, including: anemia, cardiac arrhythmia, fever, hypotension, metabolic acidosis, nausea, thrombocytopenia and organ failure, including hepatic and renal failure. Recently, second generation therapies based on IL-2 have been developed, which should increase the half-life, for example, by directed cytokine pegylation or by chimerization of the cytokine with antibodies that target the protein to the TME, and should increase pharmacodynamic properties through biotechnological methods [24,25]. Several compounds have been able to achieve clinical trial status. For example, NKTR-214 is a second generation recombinant IL-2 containing polyethylene glycol (PEG) molecules designed to prevent binding to IL-2Rα/CD25, targeting IL-2Rβ/CD122, which is found in certain immune cells (CD8+ T-lymphocytes and NK cells). IL-2 has high affinity binding to the IL-2Rα/CD25 receptor, which is highly expressed on Tregs, which can reduce the bioavailability of the cytokine for T-lymphocytes and NK cells, thereby reducing the antitumor effect. This modified cytokine is being actively tested in clinical trials in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) such as pembrolizumab (NCT03138889), nivolumab and ipilimumab (NCT03282344, NCT03435640, NCT02983045).

4. Monoclonal Antibodies

The development of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against tumor cells began in the 1970s [39]. Among therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, various types are widely used: human (adalimumab); humanized (trastuzumab), 90–95% human; chimeric (rituximab), 60–70% human; mouse (muromonab). The main idea was to target mAbs to TAAs and kill tumor cells. Destruction of target cells by mAbs can be achieved in several ways, such as direct antibody action (blockade of receptors or delivery of the target toxic agent), immune-mediated cell killing, specific antibody action on the vascular system and TME [40]. The first successes in the clinic were associated with the latter mechanism [41]. Bevacizumab, an FDA-approved angiogenesis inhibitor, is indicated for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) [42], non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [43], metastatic breast cancer (mBC) [44], glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) [45], renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [46], ovarian cancer (OC) [47] and cervical cancer (CC) [48].

Antibodies targeting TAAs are also a promising area of research. For example, the drug trastuzumab for the treatment of breast cancer [49,50], which blocks overexpression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), which sends a signal for cell growth. Pertuzumab is another recombinant anti-HER2 humanized monoclonal antibody [51]. The difference is that trastuzumab and pertuzumab bind to different domains of HER2, which gives a synergistic effect [52]. The Clinical Evaluation of Pertuzumab and Trastuzumab (CLEOPATRA) study showed the efficacy of pertuzumab and trastuzumab in combination with docetaxel compared with a combination of placebo, trastuzumab and docetaxel in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer without increasing cardiac toxicity (NCT00567190). The objective response rate (ORR) was higher in the pertuzumab group. Complete response (CR) was observed in 14 control group patients and 19 patients in the pertuzumab group. Treatment also gave a partial response (PR) for 219 patients in the first group and 256 patients in the second group [53]. There is also ongoing research on adjuvant therapy in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer (Adjuvant Pertuzumab and Herceptin in Initial Therapy in Breast Cancer (APHINITY)) (NCT01358877). The HerMES observational study evaluated the safety and efficacy of trastuzumab in patients with HER2-positive gastric cancer or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ). The median overall survival (OS) was 14.1 months, and the median progression-free survival (PFS) was 7.9 months, with ORR at 43.4%. This study confirmed the positive results of the main clinical trial—a study of Herceptin (trastuzumab) in combination with chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone in patients with HER2-positive advanced gastric cancer (ToGA study) in Germany [54].

In addition to solid tumors, a lot of attention is also paid to hematological malignancies. Hematological malignancies, unlike solid tumors, begin in the blood-forming tissue of the bone marrow and lymphoid cells. Hematologic B-cell tumors represent a large heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative disorders, including diseases such as follicular lymphoma (FL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and others [55,56]. B-cell transmembrane protein (CD20) was chosen for targeted therapy as it is expressed on most B-cells, including malignant B-cells [57]. The standard treatment among hematologic malignancies is rituximab, which is a chimeric anti-CD20 mAb for the treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, CLL, rheumatoid arthritis, Wegener’s granulomatosis and microscopic polyangiitis. Clinical trials have shown that this drug not only prolongs PFS but also increases OS in patients with lymphoma [57]. However, development of resistance in rituximab-treated patients was observed [58]. Mechanisms of resistance were explained by trogocytosis of mAb-CD20 complexes [59] and by internalization of rituximab from the surface of the B-cells malignancies [60]. Obinutuzumab is a glycoengineered, humanized anti-CD20 mAb (type II) that has been developed to increase activity by enhancing binding affinity to the FcγRIII receptor on immune effector cells and due to the ability of enhancing direct cell death and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity/antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis because of the modified elbow-hinge amino acid sequence [61].

Currently, there are 113 mAbs approved by the FDA, among which 48 mAbs, including biosimilars, are for the treatment of solid tumors and hematological malignancies. There are also mAbs which are chemically conjugated to cytotoxic drugs or radioactive isotopes for targeted delivery. For example, brentuximab vedotin is used to treat Hodgkin’s lymphoma and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). Brentuximab vedotin consists of a human chimeric immunoglobulin G1 targeting CD30, which is linked to the agent monomethylauristatin E (MMAE) via a protease-cleavable linker [62]. This drug has shown its safety and efficacy in many clinical trials, and is being moved to earlier lines of therapy in ongoing trials [63]. Other antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) that were approved by FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) are gemtuzumab ozogamicin for treating CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia in combination and as a single-agent therapy [64,65]; trastuzumab emtansine for treating HER2-positive breast cancer for patients who previously received trastuzumab and a taxane [66,67]; inotuzumab ozogamicin for treating relapsed or refractory CD22-positive B-cell precursor ALL in combination and as a single agent [68]. There are also several ADCs that are under development and are being clinically tested such as Glembatumumab vedotin, Sacituzumab govitecan, Anetumab ravtansine, Coltuximab ravtansine, Trastuzumab deruxtecan and GSK2857916 [69].

5. Vaccines

Nowadays, vaccines are the most effective treatment against infectious diseases. We have managed to prevent such diseases as smallpox, yellow fever, rubella, polio and measles [113]. There are two types of vaccines: prophylactic and therapeutic. Both types of vaccines aim to elicit specific immune responses. Preventive vaccines act against pathogenic microorganisms or oncogenic viruses (for example, human papillomavirus, HPV) based on attenuated or killed pathogens or virus-like particles (VLP). Therapeutic vaccines are based, for example, on autologous human immune cells or peptides to fight tumor cells.

Several antiviral prophylactic vaccines are already commercially available and are highly effective, including Cervarix®, Gardasil® and Gardasil9®. Gardasil® was the first vaccine to be approved by the FDA in 2006. It is a vaccine consisting of three recombinant VLPs assembled from the basic capsid protein L1 of HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18, supplemented with neutral aluminum hydroxyphosphate salt. The second generation vaccine was Gardasil9®. Its difference from its predecessor was the wider antigenic spectrum, including HPV types 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58. Cervarix® is composed of VLPs derived from the main capsid protein L1 of the HPV type 16 and 18 formulated in AS04. Cervarix® was approved by the FDA in 2007 [114]. It is not yet known whether immunization with these vaccines will last for a lifetime. It is known that the vaccines Cervarix® and Gardasil® retain their immunogenicity for at least 9 years, and according to some projections, for 20–30 years [115].

Therapeutic vaccines are aimed at activating specific CD8+ CTLs. These strategies are based on the interaction of MHC-I epitopes with TAAs. These antigens are delivered in various ways, for example, as adjuvants, to stimulate the presentation of antigen presenting cells (APCs) in vivo. There are several popular therapeutic vaccine strategies. The first strategy is a peptide-based vaccine using screening of amino acid sequences derived from TAAs for potential MHC-I epitopes [116]. The second strategy is to stimulate DCs with TAAs ex vivo, thereby producing an antitumor T-cell response upon presentation of mature optimized APCs [117,118]. The third strategy uses mitotically inactivated tumor cells or their lysate in combination with cytokines such as GM-CSF and/or adjuvants [119]. In addition, it is worth mentioning the experimental vesicle-based vaccines, which also aim to combat tumor diseases [120,121].

6. Oncolytic Viruses

There are a lot of recombinant viral vectors based on adenovirus, herpes simplex virus, smallpox virus, Coxsackie virus, maraba virus, poliovirus measles, and Newcastle disease virus. All these viruses have been used in various strategies for the treatment of cancer [175]. Most viruses are composed of three elements: the genome, the capsid, and the lipid envelope. Each type of virus has an individual structure, which is reflected in its variability when used as a tool against a tumor. For example, large eukaryotic transgenes can be encoded in DNA viruses to provide improved therapeutic activity or immune modulation, or DNA polymerases for more efficient replication. RNA viruses, for example, reoviruses, having a less capacious genome can, however, penetrate the blood–brain barrier, targeting a tumor in the central nervous system [176]. Research in the field of oncolytic viruses (OVs) as a method of immunotherapy has developed since the early 1950s [177], but over the last 15 years work has expanded more rapidly into the oncolytic capabilities of this therapy. OVs are a versatile tool for treating malignant diseases. Their antitumor activities have a wide arsenal of possibilities for the natural interaction of viruses and the immune system with tumor cells. OVs trigger selective replication in tumor cells and induce their subsequent death, thereby spreading TAAs and other factors, activating the innate and adaptive immune system [178]. Some wild-type OVs are able to recognize highly expressed receptors on the surface of tumor cells or other abnormal products or pathways in tumor cells, thereby targeting them. For example, coxsackievirus A21 (CVA21) has a natural tropism for tumor cells, recognizing highly expressed receptors and intercellular adhesion-1 molecules (ICAM-1/CD54) on the surface of tumor cells for subsequent penetration, replication, and their elimination [179]. A CVA21-based OV (CAVATAK®) has been shown to be safe and able to stimulate an anti-tumor immune response in the treatment of melanoma patients (NCT01227551, NCT01636882). Another wild-type virus, Parvovirus H1 (H1-PV), exhibits tumor selectivity for replicative and transcriptive factors and a defective type I IFN-mediated antiviral pathway in tumor cells [180]. ParvOryx (wild type H1-PV) has shown safety and evidence of immunogenic activity in the treatment of glioblastoma in phase I/IIa clinical trials. The study involved 18 patients and the median PFS was 15.9 weeks, and the median OS was 464 days [181]. In addition, the wild-type reovirus exhibited tropism towards tumor cells due to their abnormally activated Ras pathway [182]. Reolysin® (pelareorep) is a patented variant of reovirus that has received FDA approval as an orphan drug for the treatment of gastric and pancreatic cancer [183].

However, this strategy has a problem with the antiviral immune response. The immune response is quite focused on viral antigens, which reduces the effectiveness of therapy. Many options and strategies have been tried in order to solve this problem. For example, DCs, MSCs, T-cells, and cytokine-induced killers (CIKs) are used as host cells into which the virus is loaded. These host cells not only protect the virus from immune neutralization, but can also reduce the uptake of the virus by the reticuloendothelial system and bring the virus to a potential tumor site [184]. Furthermore, the replicative ability of viruses in tumor cells is a very important part of the therapy. Some viruses have an innate tropism for tumors, but other viruses require genetic editing to selectively infect tumor cells. Various strategies are used to increase the selectivity of viruses and efficiency of replication [178]. Genetic modifications of OVs are mainly reduced to the removal of virulence genes to ensure safety, as well as the inclusion of foreign genes to increase the antitumor effect and tumor selectivity [185].

7. CAR T-Cell Therapy

CAR T-cell therapy is one of the most successful experimental and rapidly developing innovative approaches to the treatment of malignant neoplasms, with a large number of registered clinical trials. The first scientific works were mostly fundamental, and scholars studied the mechanisms and role of the T-cell receptor (TCR), MHC and other coreceptors [198]. The T-lymphocyte carries a TCR, which consists of two polypeptide chains that belong to the immunoglobulin superfamily, but they are organized more simply (lack of an Fc fragment). Antibodies recognize antigenic epitopes of native protein molecules on the cell membrane. At the same time, TCR recognizes peptide fragments of antigens in complex with the MHC molecule on the cell surface. The TCR dimer chains are linked to the polypeptide chains of the CD3 complex. An activating signal formed by the interaction of TCR and peptide-MHC is transmitted through the ζ-chains of the CD3 complex for an intracellular signal. In order for TCR to recognize antigens without the participation of MHC and react on them, therefore, it was proposed that combining the antigen-binding variable domain of antibodies with the constant domain of TCR in one polypeptide may be beneficial, due to the similarity in the structure and organization of TCR and immunoglobulin [199]. The result of such experiments was first generation CAR.

CAR is a recombinant receptor located on the surface of a T-cell, which determines the specificity of this cell for the corresponding antigen and activation of the T-lymphocyte. A first generation CAR is an antigen binding variable part of a mAb (scFv) (extracellular part) and a native TCR containing a ζ-chain fragment of the CD3 complex (intracellular part). The efficacy of the first experiments with the participation of such structures was low [200,201,202,203]. Therapeutic cells underwent apoptosis after several divisions. Later it became known that for the full activation and proliferation of T-lymphocytes, it is necessary to have an interaction between the antigen and TCR in combination with MHC, as well as the interaction of costimulatory receptors (CD28, 4-1BB, OX-40) on the surface of T-cells with the corresponding ligands (CD80/86, 4-1BBL, OX-40L) on the APC. Thus, the second generation of CAR appeared, containing one costimulatory domain in addition to the scFv and CD3z domain.

Treatment efficacy of CAR varied. This therapy was most effective with the use of CD19 T-cells in B-linear ALL, and it also performed well in B-cell lymphoma and CLL. Mainly second generation CAR T-cells were used, because first generation CAR was not as effective, but the use of the costimulatory domain varied from study to study. A University of Pennsylvania study used CD19 T-cells with TCR and 4-1BB co-stimulatory domains in patients with chemotherapy-resistant or refractory ALL. In a cohort of 30 people, a single dose of autologous T-cells (1–5 × 108 CD19 CAR T-cells) were administered by split dosing: 10% on day 1 (1–5 × 107), 30% on day 2 (3 × 107–1.5 × 108) and 60% on day 3 (6 × 107–3 × 108), and the following results were obtained: patients with CR—26.7%; patients with CR with incomplete recovery of blood parameters—33.3%, with a median follow-up of 6 months [204]. In another study, therapy was performed in patients with multiple recurrent or refractory CLL. CD19 CAR T-cells (CTL019) with a 4-1BBz costimulatory domain were administered to patients with recurrent/refractory CLL at doses ranging from 0, 14 × 108 to 11 × 108 CTL019 cells (median, 1,6 × 108 cells). The cohort of patients who received CAR T-cell therapy consisted of 14 patients. Prior conditioning included cyclophosphamide and fludarabine, or pentostatin and cyclophosphamide, or bendamustine. ORR for treatment in patients with CLL was 57%, of which CR 50% and PR 50%. At the same time, CAR T-cells were preserved and remained functional for 4 years in the first two patients who achieved CR [205].

This work came from a paper 'Current Trends in Cancer Immunotherapy' by Ivan Y. Filin, Valeriya V. Solovyeva, Kristina V. Kitaeva, Catrin S. Rutland and Albert A. Rizvanov. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9059/8/12/621/htm

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biomedicines8120621