Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Tatjana Lj Marković and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

Herbaceous peonies are species with high ornamental, edible, medicinal, economic, and ecological values. Apart from their valuable roots and flowers, which contain various biologically active substances, their seeds also attract the attention of scientists.

- double dormancy release

- rare species

1. Introduction

The seeds are around 25% oil, which is rich in various unsaturated fatty acids, amino acids, and mineral elements [1][2][3][10,11,12]. The oil also has biologically active constituents that have several proven beneficial effects (antioxidant, anti-ageing, anti-UV and sunscreen, anti-tumour, etc.) [4][13]. About 30% of the dry seed weight is account for by the seed shell, which is the main co-product in peony seed oil production [5][6][7][14,15,16]. It contains cellulose, lignin, monoterpene glycosides, and crude protein and also has been proved to have several biological properties (strong antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-tumor, etc.) [8][17].

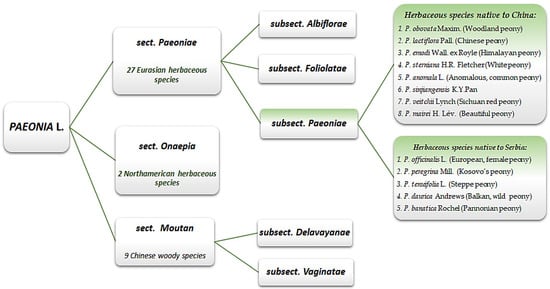

Herbaceous peonies represent the plant genus with the longest history of all flowering plants, Paeonia L. [9][10][8,18]. It is the only genus of the Paeoniaceae family and comprises about 34 species native to the northern hemisphere [11][12][19,20]. The genus is commonly divided into three sections [13][14][21,22], as presented in Figure 1, although recent study suggests reclassifying the subgenus Moutan, which includes only woody species, and the subgenus Paeonia, which includes only herbaceous species [15][23].

Figure 1. Division of genus Paeonia, with focus on herbaceous species native to Serbia and China.

All five herbaceous species native to Serbia [16][17][24,25] are rare and endangered, with the exception of the Pannonian peony (P. banatica), which is endemic, relict, and strictly protected and is, thus, listed in the Red Book of the Flora of Serbia [18][19][26,27]. Among the eight herbaceous species native to China, only the White peony (P. sterniana) is recorded in the List of National Protected Wild Plants of China as a Class II rare species [20][28].

Although peonies are generally characterized as long-lived and relatively disease- and pest-resistant plants [21][29], in many cases they are becoming rare or endangered in their natural habitats. This can mainly be attributed to climate change and/or reckless human activity [22][23][30,31], although there could be several other reasons which contribute, such as loss of habitat, inadequate nature protection policies, susceptibility to diseases, etc. [3][23][24][12,31,32].

The loss of species is a risk associated with vegetation succession [24][32]. Apart from unsustainable wild collecting practice [25][33], the trade of wild herbaceous peonies and their seeds is becoming increasingly popular [26][34]. In the last two decades, climate change has resulted in an increase in temperature, especially during the winter period, which has impacted the timing and success of germination [27][35] and/or increased the incidence of abnormal seedlings [28][36]. Plants which are not able to adapt to climate changes or shift to northern areas and/or to higher altitudes are lost from the population, making the species rare or endangered [26][27][34,35].

Herbaceous peonies spontaneously grow and thrive in temperate and cold climates [9][8] and produce seeds that are double dormant as a key protection mechanism [23][31]. To survive, plants depend on the ability to cope with changing environmental conditions. Of the different strategies that have evolved in this respect, dormancy is a widely distributed one. Double dormancy is a combination of the seed coat (external) and internal dormancy. Peony seeds require temperature variations to progress through the many stages of the germination cycle [29][37], and if they are not adequate, the survival of the entire peony population in its natural habitat is jeopardized.

Even more concerning is the low rate of peony seed dispersal in nature [3][30][12,38]. The seeds mature slowly, ripen in late summer, and disperse in autumn [31][39]. The spatial grouping of seedlings near maternal plants indicates that their dispersal is spatially limited, as confirmed in an investigation conducted in France [32][40]. The spatial aggregation of wild-growing seedlings of P. officinalis ssp. macrocarpa, their significantly greater abundance down the slope of flowering plants, and a small number of seedlings observed at distances > 1.5 m from flowering individuals all pointed to the conclusion that the species is primarily barochorous [32][40]. The data also suggest that long-distance dispersal in P. officinalis is extremely rare and that poor seed dispersal may limit colonization of the species at favorable sites [32][40].

Herbaceous peonies are generally considered self-fertile, meaning that, when isolated, their flowers self-pollinate, and their seeds produce offspring that are a genetic match to the parent plant. In the case of P. lactiflora, isolated self-pollination result in the lowest seed-setting rate of all other pollination models (natural pollination, hand cross-pollination, hand self-pollination, and natural cross-pollination) [33][41]. In addition, it was also reported that the pollination process in herbaceous peony species P. lactiflora [33][41] and P. officinalis [32][40] also requires insects or wind-mediated assistance.

Cultivating herbaceous peonies species is one of the most important strategies for preserving them. However, only a few studies have been conducted so far on the proper agronomic practices and conditions for their cultivation, particularly for propagation by seeds [34][35][36][37][42,43,44,45]. Such low interest could be attributed to the very slow germination procedure, which, in various natural conditions, can take up to 24 months [38][46].

2. Seed Properties

2.1. Physical and Morphological Properties

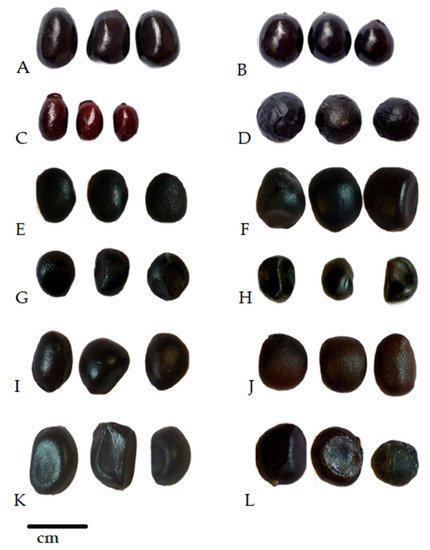

Despite the fact that morphological distinctions between the seeds of herbaceous peonies do exist (as evidenced by the literature data presented in Table 1 and supported by the seed images presented in Figure 2), it appears that they have been almost neglected in the systematics of the section Paeoniae [39][47].

Figure 2. Ripe seeds of several herbaceous peony species (seed collection, 2021); (A) P. peregrina, (B) P. banatica, (C) P. tenuifolia, (D) P. daurica, (E) P. veitchii, (F) P. mairei, (G) P. emodi, (H) P. anomala, (I) P. sterniana, (J) P. obovata, (K) P. lactiflora, and (L) P. sinjiangensis.

Table 1. Summarized literature data on seeds of most herbaceous peony species.

| Species | Seeds | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testa Colour | Size (mm) | Shape | Maturation | ||

| P. algeriensis | black | 9.0 × 7.5 | ovoid to oblong | August | [40][48] |

| P. anomala | black | 6.6–8.8 × 5.1–6.0 | ellipsoidal | August | [9][30][39][8,38,47] |

| P. banatica | black | 6.0–8.0 × 5.0 | ellipsoidal | late July to August | [41][49] |

| P. broteri | black | 7.0–8.0 | oblong | August to September | [41][49] |

| P. cambessdesii | black | 5.0 | globular | June to July | [41][49] |

| P. clusii | black | 8.0 × 5.0 | ovoid to ellipsoidal | August | [40][48] |

| P. coriacea | black | 7.0–8.0 × 5.0–6.0 | oblong | September | [40][48] |

| P. corsica | black | 7.0 × 5.0–6.0 | ovoid to globular | late July to September | [40][48] |

| P. daurica | black | 6.1–7.5 × 4.2–7.0 | globular | August to September | [30][42][38,50] |

| P. emodi | brownish black | 2.0–3.5 | globular | August to September | [43][51] |

| P. intermedia | black glossy | 5.0–5.5 × 3.0–3.5 | cylindrical to ovoid | August to September | [40][48] |

| P. lactiflora | brownish black | 5.5–10.0 × 4.1–6.8 | ellipsoidal or globular to rhomboid, flattish | late July to September | [9][30][40][42][8,38,48,50] |

| P. mairei | black with blue shine | 7.0–8.0 × 4.0–5.0 | irregular, round | July to August | [40][48] |

| P. mascula | first red than black | 7.0–8.5 × 5.0–7.0 | ellipsoidal to globular | late July to August | [42][50] |

| P. obovata | black | 6.0–7.0 × 5.0–6.0 | ovoid to globular | August to September | [40][48] |

| P. officinalis | black | 6.0–9.0 × 4.5–6.5 | obovate to ellipsoidal | late July to August | [42][50] |

| P. peregrina | black | 7.5–10.0 × 5.0–6.0 | ellipsoidal | late July to August | [40][42][48,50] |

| P. sterniana | indigo blue | 7.0–8.0 × 5.0 | ellipsoidal | August to September | [40][48] |

| P. tenuifolia | brownish black | 5.9–8.0 × 3.5–4.9 | cylindrical to ellipsoidal | July to August | [9][30][42][8,38,50] |

| P. veitchii | dark blue | 6.0 × 4.0 | ellipsoidal to oval | July | [9][8] |

| P. kesrouanensis | black | 6.0–10.0 × 6.0–8.0 | ovoid to globular | July to September | [40][48] |