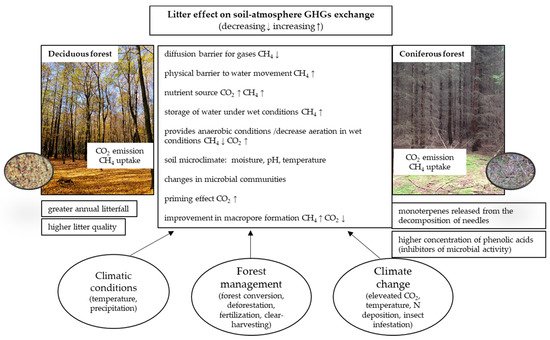

Litter can modify GHG fluxes often in gas-specific ways, although there are also common mechanisms underlying its effect, which are regulated by the environmental conditions, forest management and climate change factors.

- litter

- forest soil

- greenhouse gases

- CO2

- CH4

- climate change

- forest management

1. Introduction

Forest ecosystems are a critical component of the global carbon (C) budget through their ability to sequester and retain large amounts of CO2 [1]. An elucidation of the functioning of forest ecosystems, including their contribution to greenhouse gas (GHG) exchange, is crucial for the development of adaptation and mitigation strategies. In Europe, forests cover about 35% of the total land area, corresponding to 227 million ha with a decreasing share of coniferous (46%), broad leaved (37%), and mixed (17%) tree species [2].

Forest soils influence the GHG balance, with carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) as key elements of the global C cycle. Of the three major GHGs the CO2 flux is quantitatively often the most important and its concentration has increased by 1.9 ppm yr−1 in the last 10 years [3]. The biogenic sources of CO2 efflux from soil are root respiration, rhizomicrobial respiration, priming-related effects, and basal respiration associated with the microbial decomposition of organic matter in soils [4]. Forest ecosystems also significantly contribute to the increase in CO2 emissions through forest fires, deforestation [5][6][7][5,6,7], and CO2 release by soil microorganisms colonizing dead trees [7]. For many forests, soil CH4 is another important GHG with a global warming potential (GWP) 28 times greater than that of CO2 [8]. Soils may be a source or sink for CH4 depending on the balance between CH4 production (methanogenesis in an anaerobic environment) and CH4 oxidation (methanotrophy in aerobic conditions) [9][10][9,10]. The process of methanotrophy has significant mitigating potential since methanotrophs can contribute to a reduction in atmospheric CH4 (high affinity methanotrophy) on the one hand, but, on the other hand, can also oxidize the higher soil CH4 concentrations before this reaches the atmosphere (low affinity methanotrophy) [11]. Methanotrophy in forest soils is of particular importance, as these soils show high activity compared to soils from other ecosystems due to the dominance of high affinity methanotrophs [12].

In addition to soil, the surface litter layer can make an important contribution to C and nutrient cycling in forest ecosystems [13], changing the soil microclimate [14][15][14,15] and affecting soil microbiota. Forest litter is a layer of dead plant material present on the soil surface [16], which may be a source of nutrients and energy for soil microorganisms [17] but can also act as a bidirectional (from the atmosphere to the soil profile and vice versa) barrier to gas diffusion [3][18][19][3,18,19]. The presence of litter may modify soil–atmosphere fluxes of GHGs through different mechanisms. Due to the predicted increase in both atmospheric CO2 concentration and litter fall, the importance of the litter layer as a source of C is likely to rise [20][21][20,21], as would any indirect effects associated, for instance, with litter acting as a barrier to gas diffusion. Additionally, management practices in forests, e.g., cultivation or extensive deforestation, often result in enhanced litter fall combined with soil mixing, which accelerates its decomposition and may affect CO2 emissions [1][13][22][23][24][25][26][1,13,22,23,24,25,26]. Thus, the litter layer could be used as an indicator of the likely amount of trace gas emissions, such as CO2, from the forest soil [18]. In terms of CH4 oxidation, it has been reported that litter is more important in regulating CH4 uptake from soil than from roots [27]. The effect of litter on CH4 consumption by forests soils has been documented to be strongly dependent on the hydrological conditions [18][19][28][18,19,28]. Moreover, the regulation of soil processes and the litter layer itself may be a source or sink of GHG's [29][30][31][29,30,31], although this has received little attention [32].

Although litter can have a major impact on the C and GHG balance in forest ecosystems, this has not always been fully recognized. In this review we summarize the available information on the effects of litter on CO2 emissions and CH4 uptake in forest soils, including forest-specific impacts, environmental drivers, quantification, the influence of human activity, and the likely effects of climate change. Based on recent research, we identify a number of knowledge gaps, and directions for future research are highlighted for a better understanding of the relationship between litter and soil–atmosphere GHG (CO2, CH4) exchange, as part of the C cycle.

2. Litter as a Controller of GHG (CO2, CH4) Fluxes

Litter can modify GHG fluxes in different gas-specific ways, although there are also common mechanisms of its effect, regulated by climatic conditions, forest management and climate change factors, summarized in Figure 1 .

However, none of these effects are mutually exclusive and a litter-related increase in C substrate availability, for instance, could occur in concert with an alteration in the microbial communities of the soil and/or a lower soil temperature, as indicated in Table 1 .

| The Main Driver | Forest Type | Dominant Tree Species | Tree Age [Years] | Tree Height [m] | DBH [cm] | Tree Density [Trees/ha] | Litter Input [g/m2/year] |

MAT [°C] | MAP [mm] | Soil Type | Soil Texture (Sand/Silt/Clay [%]) |

Soil Temperature [°C] | Soil Moisture [%] |

Effect of Litter on CO2 Fluxes | Landscape Type | Location | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Litter as a source of nutrient for microbes | Plantation | T. grandis (92%) | ~10 | n/a | 10.72 ± 2.1 | 429 | n/a | n/a | 1598 | n/a | n/a | 28.78 ± 1.75 | 10.60 ± 2.42 | Increased by 14.4% ** | n/a | Jharkhand, Eastern India | [33] |

| Plantation | Eucalyptus sp. | 3 | 12 | n/a | 700 | n/a | 25 | 1200 | Arenosol (FAO) | Sandy | ~24–33 | n/a | Increased ** | coastal | Pointe Noire, Southwestern Congo | [30] | |

| regrowth forest | L. pubescens, M. sylvatica, V. guianensis, C. scrobiculata (all species represent 71% of all stems in the stand) |

12 | 4.9 ± 0.4 | n/a | 21,300 | n/a | 24–27 | 2539 ± 280 | Distrophic Yellow Latosol Stony Phase I (Brazilian Classification), Sombriustox (U.S. Soil Taxonomy) | Sandy clay loam (74/6/20) | n/a | n/a | Increased by 28% ** | n/a | Northern Brazil (1°19′ S, 47°57′ W) | [34] | |

| Plantation | Ac. mangium | 8 | 23.6 | 22.5 | n/a | 20–270 (fresh litter); 780–1130 (decayed litter); 1050–1160 (fresh + decayed litter) in wet and dry season | 27.3 | 2750 | Acrisols (WRB 1998) | n/a | n/a | 55.5–66.3% WFPS | Increased * | Undulating topography (upper and lower plateau, upper and foot slope) | South Sumatra (3°52′40″ S, 103°58′40″ E) Indonesia | [35] | |

| Pine forest | P. massoniana | 30 | 5 | n/a | 2600 | n/a | 17.8 | 1785 | Ferric Acrisols (USDA soil taxonomy) | Loamy clay (21/43/36) | 24.2 | 60.3% WFPS | Increased by 24–32% * | Hilly region | Yingtan, Jiangxi Province, Southeastern China (28°15′ N, 116°55′ E) | [3] | |

| Sclerophyll forest | Cr.alba, Q. saponaria, Pe. boldus, L. caustica | n/a | 5.06 ± 0.87 | 6.51 ± 1.39 | 2600 ± 978 | 314 ± 30 | n/a | 503 | Pachic Humixerepts | Sandy (62.4/26.4/11.2) |

n/a | n/a | Increased by 21.2–33% ** | Top slope (<4% slope) | Central Chile (34°7″ S, 71°11′18″ W) | [36] | |

| Mixed pine-broadleaf forest | Cs. chinensis (50.9%), S. superba, P. massoniana |

100 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 861 | 22.3 | 1680 | Ultisol (USDA soil taxonomy) | Lateritic | 17.5–24.0 | 20.8–27.8 | Increased by 33–38% ** | n/a | Dinghushan Biosphere Reserver, Southern China (23°09′21″ N–23°11′30″ N, 112°30′39″ E–112°33′41″ E) | [13] | |

| Pine forest | P. massoniana Lamb. (90%) | 50 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 356 | 22.3 | 1680 | Ultisol (USDA soil taxonomy) | Lateritic | 18.2–24.8 | 17.1–20.9 | Increased by 37–42% ** | n/a | |||

| Monsoon evergreen broadleaf forest | Cs. chinensis; Cr. chinensis, S. superba, Cr. concinna, Ap. yunnanensis, Ac. acuminatissima, G. subaequalis (all these species represent >60% of the community biomass) |

>400 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 849 | 22.3 | 1680 | Ultisol (USDA soil taxonomy) | Lateritic | 16.2–23.1 | 26.4–28.7 | Increased by 29–35% ** | n/a | |||

| Enhancement of anaerobic conditions by litter | Plantation | Pl. orientalis | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 15.7 | 834 | Yellow brown soil | Silty clay (11/41/48) | 16.31 ± 1.05 | 12.34 ± 0.80 | Increased by 18.84% * | n/a | Danjiangkou Reservoir, Central China (32°45′ N, 111°13′ E) | [37] |

| Soil moisture retention by litter | Mediterranean oak woodland | Qr. agrifolia | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 19 | 180 | n/a | Gravelly loam | n/a | n/a | Increased by 34.2–44.8% *** | n/a | Santa Monica Mountains, California (34°05′38″ N, 118°39′26″ W) USA | [38] |

| Montane cloud forest | Clusiaceae, Cunoniaceae, Myrsinaceae, Rosaceae, Clethraceae families | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 12.5 | n/a | n/a | Acidic | n/a | n/a | No effect ** | n/a | Peruvian Andes (13°11′28″ S, 71°35′24″ E) | [39] | |

| Pine forest | P. massoniana | 50 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 356 | 22.3 | 1680 | Ultisol (USDA soil taxonomy) | Lateritic | 18.2–24.8 | 17.1–20.9 | Increased by 37–42% ** | n/a | Dinghushan Biosphere Reserver, Southern China (23°09′21″ N–23°11′30″ N, 112°30′39″ E–112°33′41″ E) | [13] | |

| Mixed deciduous forest | Ar. rubrum, Qr. rubra | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 8.5 | 1050 | Typic Dystrochrept | Fine sandy loam | n/a | n/a | Increased ** | n/a | Harvard Forest, Petersham, Massachusetts (42°32′ N, 72°11′ W) USA | [40] | |

| Old-growth semidecidous tropical forest | n/a | n/a | n/a | >35 | n/a | n/a | n/a | >2000 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Increased ** | Flat plateau (the planalto) | Pará, Northern Brazil (3°0′37 S, 54°34′53″ W) | [41] | |

| Priming effect | Old-growth moist lowland tropical forest | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 27 | 2600 | Oxisol | n/a | n/a | n/a | Increased by 20% ** | n/a | Gigante Peninsula, central Panama (9°06′ N, 79°54′ W) | [42] |

| Undisturbed old-growth forest | Ts. heterophylla, Ps. menziesii |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 8.7 | 2370 | Typic Hapludands | Coarse loamy | 9.5 | 29 | Increased ** | n/a | H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, Oregon (44°13′ N, 122°13′ W) USA | [23] | |

| Undisturbed old-growth forest | P. menziesii, T. heterophylla |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 8.7 | 2370 | Typic Hapludands | Coarse loamy (13% clay) |

9.5 | 29 | Increased by 19% and 58% ** | n/a | H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, Oregon (44°15′ N, 122°10′ W) USA | [43] | |

| Temperate deciduous forest | Q. petraea (70%), Cp. betulus (30%) |

100–150 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 10.7 | 680 | Gleyic Luvisol (WRB 2006) | Loam (41.9/38.8/19.3) |

2.7 ± 0.5 | 20.4 ± 0.6 | Increased ** | n/a | Barbeau National Forest, Northern Central France (48°29′ N, 02°47′ E) | [20] | |

| Mixed deciduous temperate woodland | Ar. pseudoplatanus, Fr. excelsior |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 10 | 714 | Stagni-vertic Cambisol (FAO/WRB) | Clay loam | n/a | n/a | Increased by 30% ** | n/a | Wytham Woods, Oxfordshire (51°43′42″ N, 1°19′42″ W) UK | [44] | |

| Semi-deciduous lowland tropical forest | Arecaceae, Burseraceae, Olacaceae families | 200 | n/a | ≥10 | n/a | n/a | 27 | 2600 | Clay-rich Oxisol | n/a | n/a | n/a | Increased by 10% ** | n/a | Gigante Peninsula, central Panama (9°06′ N, 79°54′ W) | [44] | |

| Litter can act as an insulating layer that also buffers the effects of variations in light, temperature and irradiation | Temperate deciduous forest | Qt. petraeae-cerris community | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2930 | 10.7 | 615.6 | Brown forest soil, Cambisols (FAO) | n/a | 9.94 | 25.4 | Reduction **** | n/a | Bükk Mountains, Northeastern Hungary (47°55′ N, 20°26′ E) | [21] |

| Temperate deciduous forest | Qt. petraeae-cerris community | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2754 ± 206 kg C ha−1 yr−1 | 10.8 | 599 | Cambisol | n/a | 11.4 ± 0.93–16.1 ± 0.78 | 12.8 ± 0.78–28.4 ± 1.39% v/v (soil) | Reduction **** | n/a | Bükk Mountains, Northeastern Hungary (47°55′ N, 20°26′ E) | [45] |

The diffusion of CH4 from the atmosphere into the soil strongly affects CH4 consumption, since the upper-most well-aerated mineral soil located immediately underneath the organic layer exhibits the highest methanotrophic activity [28][46][28,75]. The mechanisms associated with the effects of litter atmospheric CH 4 uptake by soils are regulated by moisture [19][27][32][19,27,32], as CH4 diffusion is 10 4 times slower in water than in air [47][76].

It is difficult to quantify the effects of litter or litter quality on GHG emissions because of the paucity of reliable data. Two examples (the Figure A1 in Appendix A ) indicate that the effects of litter can vary depending on the GHG under consideration, with a positive effect of litter amount on CO2 fluxes but a negative effect on CH4 fluxes, assuming that litter thickness reflects the amount of litter present. The correlations are significant but could be influenced by a range of other factors, e.g., variation in soil conditions, tree species, and climate zones.

3. Tree Species-Specific Mechanisms of the Effects of Litter on GHG Fluxes

The contribution of the litter layer to respiration ranged from 5% to 45% of the total CO2 emissions from temperate forests soils [3]. The emissions of CO2 were confirmed to be often lower in coniferous forest soils than in deciduous forests [48][97]. A meta-analysis revealed that natural and doubled litter inputs increased soil respiration in forest ecosystems by 36% and 55%, respectively. The effect of litter inputs on the increase in soil respiration in different types of forests was of the following order: coniferous forests (50.7%) > broad-leaved forests (41.3%) > mixed forests (31.9%) [49][89]. In coniferous forests, the removal of litter caused a reduction in CO2 emissions, ranging from 2.61% in a fir forest in Poland to 68% in a Pinus caribeae plantation in Puerto Rico [50][39]. After the litter layer removal in a pine forest, CO2 emissions were reduced by 43%, while CH4 uptake increased more than twofold under dry and warm soil conditions [51][78].

Broad leaf forests were found to have a relatively higher mean annual litter fall and a higher litter quality compared to mixed or pine forests [52][53][102,103]. The removal of litter reduced CO2 emissions, to varying extents, depended on the type of deciduous tree species. In hornbeam oak forests, soil respiration decreased only slightly: from 2.88 kg CO2 m −2 year −1 ( with litter research point) to 2.78 kg CO2 m −2 year −1 (litter-free research point), but in the acidophilous beech forest, CO2 emissions decreased from 2.18 kg CO2 m −2 year −1 to 1.32 kg CO2 m −2 year −1 after excluding litter. The amount of CO2 emitted from forest soils also depended on the rate of litter decomposition, which differed in different types of forests [54][42]. A beech stand was found to have the slowest litter decomposition, and its accumulation was approximately two to three times higher than in mixed stands of deciduous tree species [55][104]. Similarly, in a hornbeam oak forest litter decomposition processes were faster and CO2 was released more rapidly than in a beech forest. It was estimated that the average decrease in soil respiration globally after litter removal was 27% for different types of forests. The litter decomposition rate, along with soil respiration decreased after litter removal, in a seasonally flooded forest and an upland forest where litter removal resulted in a 10–20% reduction in soil respiration [56][105]. Therefore, it can be concluded that the rate of litter decomposition made a significant contribution to differences in soil CO2 emissions between various ecosystems. Tropical forests were very important in this context [42][50], and may have contributed about 67% to the total annual global CO2 efflux [56][105]. These forests could react differently to litter manipulations, since they differed from temperate forests in terms of soil age, biotic composition, erosion, and/or uplift rates [57][58][106,107]. Tropical and subtropical forests may also have varied significantly in soil abiotic (e.g., soil moisture and temperature) and biotic (e.g., litter quantity and quality, tree species) factors, which also influenced the impact of litter inputs on CO2 emissions [50][57][59][60][39,106,108,109].

Similar to CO2 emissions, forest types differ in soil CH4 uptake ability. The high consumption of atmospheric CH4 by forest soils confirms the involvement of high affinity methanotrophs [12] and the process is carried out by different groups of methanotrophs [61][110]. Among the most abundant methanotrophs, Methylocystis spp. and Methylococcus more often populate deciduous forest soils than mixed and coniferous forest soils [62][111]. A number of studies conducted under the same climatic conditions also indicate that tree species affect CH4 uptake in forest soils, with deciduous forests consuming more CH4 than coniferous forests [28][40][63][64][28,48,112,113]. One of the explanations for this is that it is due to vegetation and soil-related differences in the structure and activity of methanotroph communities [62][65][111,114]. Of the factors that could be important, litter and soils from coniferous forests have a lower pH than deciduous stands, typically ranging between 3 and 4 in pine-dominated forests [66][67][68][69][115,116,117,118]. Such conditions are below the optimum typical level for methanotrophs [70][119] and may result in a lower CH4 uptake; however, some methanotrophs have adapted to such conditions in forest soils [71][120]. A study on different temperate tree species shows that soil under beech trees is more acidic and has lower inputs of Ca and Mg via litter in comparison with mixed stands of deciduous tree species [72][55][96,104].

The properties of the litter itself are also an important factor. Litter in deciduous forests is characterized by a higher degradability than in coniferous forests, which results in higher soil N turnover rates [73][121]. Strong interactions between CH4 oxidation and soil N have also been reported [74][75][76][122,123,124]. In temperate forests, N fertilization is reported to reduce the CH4 sink [77][125] due to a salt effect [78][126] or a higher nitrification rate [79][127]. In subtropical forests, N deposition can suppress CH4 uptake by altering methanotroph and methanogen abundance, diversity, and community structure [80][128].

4. Environmental Controllers of the Impact of Litter on GHG Fluxes

Consideration of the litter effect on soil GHG fluxes should include the role of climatic conditions, mainly temperature and precipitation. Due to the dynamics of these parameters, the litter effect on GHG fluxes may show significant seasonal variability.

In an oak forest rainfall is reported to increase CO2 emissions, which results in the rapid reactivation of litter-associated microorganisms [38][46]. On the other hand, in a tropical montane cloud forest in Peru, lower moisture levels do not change the soil respiration after litter removal, which is explained by the fact that the litter and organic matter are decomposed by microorganisms with different moisture sensitivities [39][47]. Litter respiration also depends largely on moisture content, and the contribution of litter to soil respiration is influenced by the frequency and amount of precipitation [38][40][81][82][46,48,134,135]. Warm and humid climatic conditions accelerate organic matter decomposition, resulting in increased rates of soil respiration [83][100]. Changes in the water content of the litter layer are often transient, since litter is directly exposed to wind and solar radiation [84][136]; nevertheless, they can influence CO2 emissions, and therefore the overall forest CO2 budget [85][137]. Continuous cycles of wetting and drying of the litter layer led to transient CO2 emissions [84][86][136,138]. An increase in CO2 emissions followed by an increase in the litter moisture content due to rainfall was also reported in a semi-deciduous old-growth tropical forest (with mostly evergreen species) [41][49] and in a forest dominated by Quercus serrata Thunb. [84][136]. Studies carried out in coniferous and deciduous forests in different locations in Europe (Italy, the Netherlands, and Finland) show that leaf litter is the main source of CO2 and the emissions peaked at the higher moisture contents for all types of litter, temperatures, or sites, while the optimum soil CO2 emissions are achieved at intermediate moisture contents (40–70% WFPS) [87][88]. Litter removal causes a decrease in soil moisture [15] (compared to soil with litter) and when soil moisture is low, both the transport of nutrients and the metabolism of decomposing microbes are reduced [88][89][139,140].

Hydrological conditions are a strong regulator of the CH4 cycle since saturated (flooded) soil can be a source of methane, while well-aerated soil can be a sink of this gas [10]. After a high rainfall in the temperate zone or during the wet season in a tropical climate, soil may also emit CH4, although the net exchange between soils and the atmosphere depends on how this impacts the balance between CH4 production and consumption [19]. The strong dependence of CH4 oxidation on water content is confirmed as litter addition during the dry season does not significantly affect CH4 uptake, while it decreases it by 47.1 ± 4.9% during the wet season after doubling the litter level [27]). The litter effect may result from enhanced microbial activity and/or from changes in litter quality and decomposition rate [16]. It is reported that litter may store water during rainfall events. Since water cannot penetrate the mineral soil, a high soil diffusivity is maintained [28]. However, a study on different types of needle leaf and broad leaf litters revealed that the rainfall interception storage capacity of the litter layer varied with physical features and rainfall characteristics [90][93]. The interception-related storage capacity of needle leaf litters varied significantly with the litter type, while there were no significant differences in water storage across the broad leaf litter types. It was reported that a higher intensity or longer duration of rainfall events could increase the interception storage capacity in all broad leaf and needle leaf litters [90][93].

The litter layer was an effective insulator, isolating the soil from the effects of variations in irradiance, consequently lowering soil temperature [21]. In a deciduous forest, litter and soil temperatures were responsible for 68% to 81% of the variability in CO2 emissions, respectively [83][100]. When there was no litter on the soil surface, the influence of temperature on soil respiration was higher, the activity of soil microbes and their enzymes increased, and the degradation of organic matter was greater. Thus, under these conditions, an increase in soil CO2 emissions could often be observed [21][91][92][93][21,141,142,143]. After the removal of litter in a Quercetum petraeae-cerris forest in northeastern Hungary, the soil was found to reach higher temperatures in summer and lower temperatures in winter [45][37]. The greatest reductions in CO2 emissions after litter exclusion were observed in a Cinnamomum camphora forest in China (39.2%) [94][144], in a beech ( Fagus sylvatica ) forest in Poland (about 39.45%) [54][42], and in a wet tropical forest dominated by Tabebuia heterophylla in Puerto Rico (54%) [50][39].