Lung cancer represents the first cause of death by cancer worldwide and remains a challenging public health issue. Hypoxia, as a relevant biomarker, has raised high expectations for clinical practice.

- non-small cell lung cancer

- hypoxia

- HIF

- angiogenesis

- oxygen sensing

- lung cancer management

Introduction

2. Biological Features Associated with Hypoxia in NSCLC

2.1. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Detection in Whole Tumour Tissues

2.2. Tumour-Initiating Cells and Hypoxic Conditions

2.2.1. Cancer Stem Cells Are Influenced by Hypoxia

2.2.2. Epithelial to Mesenchymal Polarization by Hypoxia

2.3. Tumour Microenvironment Features in Hypoxic Condition

2.3.1. Hypoxia-Driven Stroma Modifications

2.3.2. Inflammation Landscape in the Hypoxic Context

2.3.3. Immune Checkpoint Disruption by Hypoxia

2.4. Molecular Signature of Hypoxic Tumours

2.4.1. Metabolic Consequences of Hypoxia

2.4.2. Hypoxia Widely Impairs Cancer Gene Expression

2.4.3. Hypoxia Supports Molecular Alterations

2.4.4. EGFR and ALK Genes Are More Frequently Altered in Hypoxic NSCLC Tumours

3. Available Tools to Detect Hypoxia in Clinical Practice

| Hypoxic Marker | Biological Material | Method of Assessment | Observation | Clinical Interest | Advantage | Limitation | Patients (n) | REF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIF-1 α | Tumour cells | Histological | ↑ expression associated with lymph node metastasis | Staging | Reproducible | Variability on HIF-1α threshold of positivity and its intracellular localization | 1436 | [38] |

| Tumour cells | ↑ expression associated with ↓ OS | Prognosis | 1049 | [38] | ||||

| 1113 | [47] | |||||||

| 256 | [136] | |||||||

| Serum concentrations | Circulating blood marker | ↓ serum concentration during chemoradiotherapy course | Response monitoring | Mini-invasive procedure Reproducible Real-time monitoring |

No control group | 80 | [137] | |

| HIF-2 α | Tumour cells | Histological | ↑ expression associated with ↑ stages ↑ expression associated with ↓ OS |

Staging Prognosis |

Reproducible | Restricted to stages I to III No association with HIF-1 α expression |

140 | [50] |

| Ang-2 | Tumour cells | Histological and mRNA expression | ↑ expression associated with ↑stages ↑ expression associated with ↓ OS |

Staging Prognosis |

Reproducible | mRNA expression not currently transposable in clinical routine Significance restricted to AC subgroup |

1244 | [46] |

| Serum concentration | Circulating blood marker | ↑ concentration associated with lung cancer (Se 92.5 and Sp 97.5%) | Diagnosis | Mini-invasive procedure Reproducible Real-time monitoring |

High threshold | 228 | [43] | |

| ↑ expression associated with ↑ stages ↑ expression associated with ↓ OS |

Staging Prognosis |

- | 575 | [44] | ||||

| GLUT-1 | Tumour cells | Protein and mRNA expression | Co-expression with PD-L1 ↓ co- expression associated with ↑ OS |

Prognosis | Reproducible | No evaluation of ICI sensibility | 295 | [104] |

| CA-IX | Serum concentration | Circulating blood marker | ↑ concentrations associated with ↓ survival rates under radiotherapy | Prognosis | Mini-invasive procedure Reproducible Real-time monitoring |

Small effective | 55 | [138] |

| Flow extraction product | CT radiomic analysis | CT features | ↓ enhancement associated with lymph node metastasis Correlation with GLUT expression | Staging | Radiometabolic hypoxia-related markers | Small effective Non-standardised techniques of acquisition and analyses |

14 | [139] |

| Standardised Uptake Values (SUV) | PET radiomic analysis | Metabolic features | Correlation with histological HIF-1α expression | Not established | Non-invasive procedure Tumour heterogeneity consideration |

No investigation on prognosis | 288 | [140] |

| OPN | Serum concentration | Circulating blood marker | ↑ concentrations associated with ↓ OS | Predictive of ↓ outcomes with chemoradiotherapy Predictive of ↓ outcomes with radiotherapy Predictive of tumoural response and prognosis with chemoradiotherapy |

Non-invasive procedure Tumour heterogeneity consideration Reproducible Real-time monitoring |

Included in a multiparametric model with other proteins | 263 | [141] |

| Small effective | 44 | [142] | ||||||

| 81 | [143] | |||||||

| 55 | [138] | |||||||

| Significance restricted to SqCC subgroup | 337 | [144] | ||||||

| VEGF | Tumour cells | Histological and mRNA expression | ↑ concentration associated with ↓ OS | Monitoring of tumoural response under chemoradiotherapy | Reproducible | Variability on VEGF threshold of positivity and intracellular localization | 1549 | [145] |

| Serum concentration | Circulating blood marker | ↑ concentration associated with ↓ OS | Predictive of response and prognosis with immunotherapy | Non-invasive procedure Tumour heterogeneity consideration Reproducible Real-time monitoring |

Significance restricted to elderly (>75 y.o) or PS > 2. | 235 | [146] | |

| ↑ concentration associated with ↓ survival rates under radiotherapy | Predictive of ↓ outcomes with radiotherapy | Small effective | 55 | [138] | ||||

| bFGF | Serum concentration | Circulating blood marker | ↑ concentration associated with ↓ OS | Monitoring of tumoural response under chemoradiotherapy regimen | Non-invasive procedure Tumour heterogeneity consideration Reproducible Real-time monitoring |

Variability on bFGF threshold of positivity | 358 | [147] |

| miR-21, miR-128, miR-155, miR-181a | mi-RNA serum concentration | Circulating blood marker | Prediction of outcomes with first-line chemotherapy | Predictive of tumoural response Prognosis |

Non-invasive procedure Reproducible Real-time monitoring |

Not currently transposable in clinical routine Significance restricted to SqCC subgroup | 128 | [148] |

| CA-IX, CCL20, CORO1C, CTSC, LDHA, NDRG, PTP4A3, TUBA1B |

Gene expression signature | mRNA expression | Predictive of hypoxic tumours associated with ↓ OS Co-expression with TILs infiltration |

Prognosis | Non-invasive procedure Reproducible Real-time monitoring |

Not currently transposable in clinical routine | 515 | [97] |

3.1. Hypoxic Characterisation by Imaging Techniques

3.1.1. Using Radiomics on Computed Tomography Images to Identify Hypoxic Tumours

3.1.2. Positive Emission Tomography Radiotracers Identify Hypoxia

3.1.3. Conventional [18F]-FDG PET to Explore Hypoxia

3.1.4. Current Limitations for Hypoxia Characterisation by PET

3.2. Circulating Markers to Help Clinicians Classify Hypoxic Tumours

3.2.1. Soluble Blood Proteins Are Promising for the Identification of Hypoxic Tumours

3.2.2. Tumour Circulating DNA/RNA Provide Hypoxia-Related Signatures

3.2.3. Circulating Tumour Cells Associated with Hypoxic Tumours

3.3. Emerging Approaches in Hypoxic-Tumour Identification

4. Prognostic Implications of Hypoxia in Lung Cancer

4.1. Early and Locally Advanced Stages

4.1.1. Hypoxia Is Associated with Higher Tumour Stages

4.1.2. Hypoxia-Associated SNPs Revealed Higher Lung Cancer Risks

4.1.3. Hypoxia as a Prognostic Marker for Resected Tumours

HIF-1α Expression Is Associated with Worse Clinical Outcomes

Hypoxia Related Prognosis and HIFs

4.1.4. Characterisation of Hypoxia to Improve the Clinical Course in Locally Advanced Stages

Current Strategy in Non-Resectable and Local NSCLC

Hypoxic Features to Predict and Monitor Tumour Response

4.2. Metastatic Stages: Potential Hypoxia-Related Treatment Strategies, from Response to Resistance

4.2.1. Hypoxic Tumours Are Associated with a Higher Risk of Distant Metastasis

4.2.2. Chemotherapy

4.2.3. Immunotherapy

Current Use of Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors

Hypoxia as a Predictor of Response under ICI Regimens

4.2.4. Radiotherapy

Hypoxic Imaging to Guide Radiotherapy Strategies

Biological Hypoxia-Related Markers Improving Radiotherapy Success

4.2.5. Targeted Therapies

KRAS

EGFR

- •

-

Current Clinical Application of becanti-EGFR in NSCLC

- •

-

Hypoxia Could Predict Non-Response to EGFR TKIs in Wild-Type EGFR NSCLC

- •

-

Hypoxia Led to EGFR TKIs Resistance in Mutant EGFR NSCLC

- •

-

Promising Strategies to Overcome Hypoxia-Mediated Resistance with EGFR-TKIs

ALK

5. Hypoxia-Related Treatments and Research Development

5.1. Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase (PDK) Inhibitors

5.2. Metformin

5.3. Vorinostat

5.4. Nitroglycerin

5.5. Tirapazamine

5.6. Efaproxiral

5.7. Anti-Angiogenic Therapies

2. Biological features associated with hypoxia in NSCLC

2.1. Hypoxia-inducible factor detection in whole tumour tissues

2.2. Tumour-initiating cells and hypoxic conditions

2.3. Tumour microenvironment features in hypoxic condition

2.4. Molecular signature of hypoxic tumours

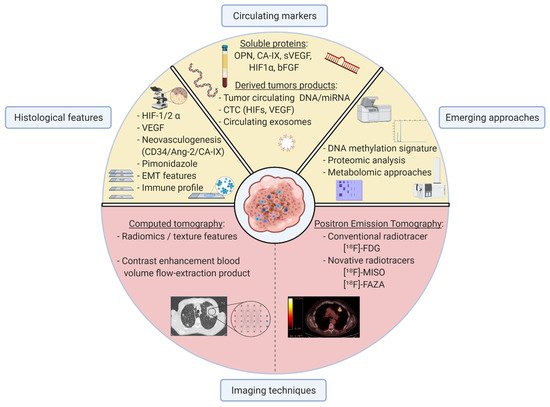

3. Available tools to detect hypoxia in clinical practice

3.1. Hypoxic characterisation by imaging techniques

3.2. Circulating markers to help clinicians classify hypoxic tumours

3.3. Emerging approaches in hypoxic-tumour identification

4. Prognostic implications of hypoxia in lung cancer

4.1. Early and locally advanced stages

4.2. Metastatic stages: potential hypoxia-related treatment strategies, from response to resistance

5. Hypoxia-related treatments and research development

5.1. Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase (PDK) inhibitors

5.2. Metformin

5.3. Vorinostat

5.4. Nitroglycerin

5.5. Tirapazamine

5.6. Efaproxiral

5.7. Anti-angiogenic therapies

6. Conclusions

In this study, we conducted an extensive review of the potential impact of hypoxia in each stage of NSCLC and highlighted clinical and pathological features related to hypoxic tumours relevant to clinicians. It appears that some tumours are more frequently associated with hypoxic regions than others, such as poorly differentiated SqCC presenting a tumour microenvironment including high tumoural microvessel density and stroma-enriched immune cells harbouring epithelial-to-mesenchymal polarization. The current challenge to identifying hypoxia remains the definition of relevant thresholds for markers discriminating hypoxic from non-hypoxic tumours. Pathological examinations and immunostainings are needed to validate further markers in paired and matched comparison studies. The identification of biological signatures based on nucleic acid expressions may contribute to the development of hypoxic-scores after validation in larger and design-dedicated cohorts. Systematic genetic association studies taking hypoxia as a relevant parameter will ideally complement the translational approach. We also reviewed current promising approaches allowing to evaluate hypoxia in the NSCLC context with a special interest in the most suitable and transposable approaches in clinical routine. Tumour hypoxia biology is complex and in constant evolution over time, given that sequential drugs and radiation use lead to resistance and treatment escape. We finally investigated how hypoxic characterisation could influence the major steps of lung cancer clinical management. For patients with early cured NSCLC, transversal hypoxic tumour determination might also be of interest to isolate and predict those who would benefit from adjuvant therapies to reduce the risk of relapse. Nonetheless, challenges and clinical goals are specific in advanced and metastatic stages when aiming to predict tumour response across various regimens of treatments. In these later stages, longitudinal hypoxic characterisation might be the most relevant approach. Repeated PET/CT scans and more strikingly, circulating hypoxia-related markers may enable monitoring of tumour variations and adaptation of clinical strategies in a personalised approach. Despite limitations to hypoxia implementation in lung cancer clinical management, evidence is accumulating for its consideration, including dedicated hypoxia-related treatments. Hypoxia characterisation could improve the outcome of patients with NSCLC and might represent the next step to a personalised medical protocol in the field of cancer.