Poor oral hygiene is the primary cause of common oral diseases. and has been found to be associated with low-gradeAccumulation of dental plaque allows bacterial growth that may lead to inflamed periodontal tissues and eventually create bacteremia and systemic inflammation, suggesting its potential link to metabolic syndrome (MetS). Invading bacteria from severe caries or endodontic infections is also thought to provoke similar mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS), a clustering of abdominal obesity, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, represents a growing public health concern globally [1][1]. Although the prevalence of MetS differs depending on diagnostic criteria, age group, and ethnicity [1,2], it is estimated to affect around 25% of the world population [2,3]. MetS raises the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and cardiovascular diseases [1] and is associated with a 20% increase in healthcare costs [4].

Several risk factors for MetS have been identified. Besides socioeconomic status (SES) [2][5], smoking [3][6], diet [4][7], and physical activity [5][8], oral diseases, such as periodontal diseases and dental caries, are associated with MetS [6][7][8] [9,10,11]. PoorThe oral hygiene is the primary cause of common oral link between oral and systemic diseases and is associated with low-grade inflammation [9]is suggested due to common risk factors, subggesting its potential link to MetSingival biofilm harboring Gram-negative [10].

Albacthough several epidemiological studies have reported ia, and periodontium serving as a cytokine reservoir [12].

Toothe association of oral hygiene statusbrushing and interdental [11] cleanding, cwhich are [10][12] with MetS, some studies found no such association [13][14]. To da main forms of oral self-care, togethe, there has not been a systematic review conducted on the topic. A summary of evidence can provide a better understanding of the potential relationship and helpr with regular professional care, are important measures for plaque control or removal and maintaining optimal oral healthcare [19,20,21]. practitiPooners deliver more targeted care. This systematic review andr oral hygiene care is associated with low-grade inflammation [22], msuggeta-analysis aimed to evaluatesting its potential link to MetS [23]. tThe associations of or of poor oral hygiene status and care with MetS.

2. Methods

Ba higher riesk ofly, a systematic search of the PubMed and Web of the components of MetS, such as obesity [24], Scdience databases fromabetes [25,26], inchypeption to 17 March 2021rtension [26,27], and dyslipidexaminationmia [26,28], ofas reference lists was conducted to identify eligible studies.well as with cardiovascular disease [14,22], The inclusion criteria incas been demonstrated.

Althoude observationgh several epidemiological studies that examinhave reported the association of oral hygiene status (e.g.,[29] oral hygiene index, plaque nd care [23,30] windth Mex, plaque score) or care (i.e., tooth brushing, interdental cleaningtS, some studies found no such association [31,32]. andTo dental visit) with MetS. Two authors independently conducted study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment of the studies. Any ambiguities or disagreements were resolved by consensus. Meta-analysis was conducted separately for different types of exposure (i.e., oral hygiene status, tooth brushing, and interdental cleaning). A random-effects model was applied to pool the effects of oral hygiene status and care on MetS. Potential sources of heterogeneity were assessed using prate, there has not been a systematic review conducted on the topic. A summary of evidence can provide a better understanding of the potential relationship and help healthcare practitioners deliver more targeted care. It can provide more substance for the formulation of public health programs and policies, especified subgroup analyses by study desigally strategies for the prevention and countrymanagement of MetS.

32. ResultAssociation between Oral Hygiene Status, Care, and MetS

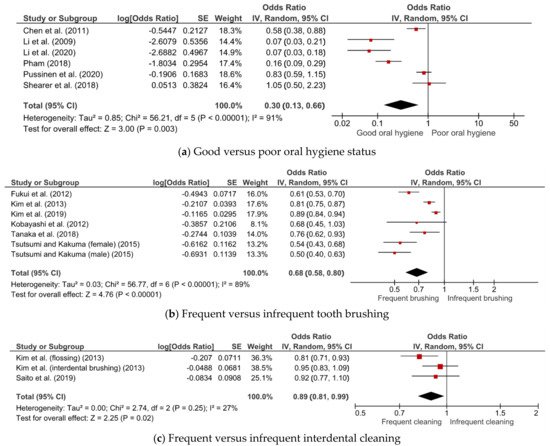

TFigure 1 shirows teen studies met the inclusion criteria and had sufficient methodological quality. Overall, ghe results of the meta-analysis of associations of oral hygiene status, tooth-brushing frequency, and interdental cleaning with MetS. Good oral hygiene (OR = 0.30; 95% CI = 0.13–0.66), frequent tooth brushing (OR = 0.68; 95% CI = 0.58–0.80), and frequent interdental cleaning (OR = 0.89; 95% CI = 0.81–0.99) were associated with a lower risk of MetS. While heterogeneity was minimal for interdental cleaning (I2 = 27%), there was substantial heterogeneity for oral hygiene status (I2 = 91%) and tooth-brushing frequency (I2 = 89%).

Figure 1. Meta-analysis of the associations of (a) oral hygiene status, (b) tooth-brushing frequency, and (c) interdental cleaning with metabolic syndrome.

The association between dental visits and MetS was evaluated only in a study by Tanaka et al. It was found that dental visits were not significantly associated with MetS (OR = 1.10; 95% CI = 0.77–1.55)

[10][23].

Subgroup analysis

3. Subgroup Analyses

Table 2 displays the results of subgroup analysis by study design for the association between oral hygiene status and MetS. The inverse association between oral hygiene status and MetS was only observed in the subgroup of case-–control studies. Subgroup analysis of oral hygiene status by study design reduced heterogeneity to less than 50%. Frequent tooth brushing was consistently associated with a lower risk of MetS in all subgroup analyses. However, high heterogeneity was still observed among these studies with a cross-sectional design. While subgroup analysis of tooth-brushing frequency by country reduced heterogeneity, it remained above 50%.

4

Table 2. Subgroup analysis by study design for the association between oral hygiene status and MetS.

| Subgroup |

Number of Studies |

OR (95% CI) |

I2 (%) |

p |

| Cross-sectional |

2 |

0.72 (0.41–1.26) |

46 |

0.17 |

| Case–control |

3 |

0.11 (0.06–0.20) |

39 |

0.19 |

| Cohort |

1 |

0.83 (0.59–1.15) |

- |

- |

3. Conclusion

OurThe study found that there might be association between dental visits and MetS was not demonstrated in the study by Tanaka et al. [23]. This fin

vding was similar to another

se study demonstrating no associations

of oral hygiene status, tooth-brushing frequency, and interbetween dental visits, professional dental cleaning, and diabetes. It was argued that other confounders had more important roles in the development of diabetes than professional dental cleaning

with MetS[25]. However,

substan

tial heterogeneity for tooth-brushing frequenc earlier review has demonstrated the benefit of scaling and root planing on metabolic control and systemic inflammation reduction in patients with T2DM [69].

This entry and

imeta-an

consistent results foralysis was the first to explore the association of oral hygiene status

in subgroup analyses were observed. There was insufficieand care with MetS. The topic is seen as recent in the scientific literature, with the earliest identified studies published in 2009. It is also related to an emerging interest in the interrelationships between oral pathogens, oral microbiome dysbiosis, and systemic conditions [70]. Explorin

g t

evidence on the association betweehis topic is relevant considering the importance of formulating policies with common risk factors approach to address both oral and general health [71]. An

other dental visits and MetSstrength of our review was the quality of the studies, which was moderate to high.

The Fresurther well-conducted studies, preferably of longitudinal design, are needed to confirlt might be limited by the methodological weakness of the included studies with a cross-sectional design. The number of cohort studies was also limited. Moreover, the restriction of studies to those published in English and the exclusion of a grey literature search might introduce bias. The risk of publication bias could not be ruled out and was not assessed in the current study due to an inadequate number of studies and high heterogeneity. Besides study design and country, the potential source of heterogeneity might be from the associationvariability in measurement methods of oral hygiene status and care with MetS a(e.g., the use of different indices) and the reporting of tooth-brushing frequency and interdental cleaning between studies. Moreover, the criteria used to define MetS varied.

Information on tooth-brushing frequency and to explore their underlying mechanisms. Research on this topic will provide a valuable contribuinterdental cleaning was self-reported, which might be prone to bias. However, it might only be the type of nondifferential misclassification, leading to the underestimation of true effect estimates. Regular brushing does not necessarily reflect effective brushing, as the studies did not adjust for the duration and method of tooth brushing and the type of dentifrice used.

Finally, most of the ion to our current understandingncluded studies in our review were conducted among an Asian population, which may influence the generalizability of the interrefindings worldwide. Further research conducted among other populationship between is warranted to provide more evidence. Using a uniform protocol for reporting oral health and MetSygiene (e.g., tooth-brushing frequency) may also facilitate better comparison.