Children are commonly exposed to second-hand smoke (SHS) in the domestic environment or inside vehicles of smokers. Unfortunately, prenatal tobacco smoke (PTS) exposure is still common, too. SHS is hazardous to the health of smokers and non-smokers, but especially to that of children. SHS and PTS increase the risk for children to develop cancers and can trigger or worsen asthma and allergies, modulate the immune status, and is harmful to lung, heart and blood vessels. Smoking during pregnancy can cause pregnancy complications and poor birth outcomes as well as changes in the development of the foetus. Lately, some of the molecular and genetic mechanisms that cause adverse health effects in children have been identified. It has been found in children that SHS and PTS exposure is associated with changes in levels of enzymes, hormones, and expression of genes, micro RNAs, and proteins. PTS and SHS exposure are major elicitors of mechanisms of oxidative stress. Genetic predisposition can compound the health effects of PTS and SHS exposure. Epigenetic effects might influence in utero gene expression and disease susceptibility. Hence, the limitation of domestic and public exposure to SHS as well as PTS exposure has to be in the focus of policymakers and the public in order to save the health of children at an early age. Global substantial smoke-free policies, health communication campaigns, and behavioural interventions are useful and should be mandatory.

- environmental tobacco smoke

- passive smoke

- smoking in pregnancy

- maternal tobacco smoke

- asthma

- allergy

- atopy

- immunity

- wheezing

- genetic predisposition

1. Introduction

Second-hand smoke (SHS) consists of mainstream smoke exhaled by a smoker and side-stream smoke from the smouldering tobacco product[1] [1]. The terms “environmental tobacco smoke (ETS)” and “passive smoke” as synonyms for SHS are common but were also described as the sum of SHS and third-hand smoke[2] [2].

2. Influence of Second-Hand and Prenatal Tobacco Smoke in Children

Important sources of SHS exposure are the workplace, public places where smoking is allowed, smoker’s homes and vehicles. In particular, homes and vehicles are loci where children and pregnant women can be exposed to SHS[3] [3]. Unfortunately, exposure to SHS in private homes and vehicles is still common[4][5] [4,5].

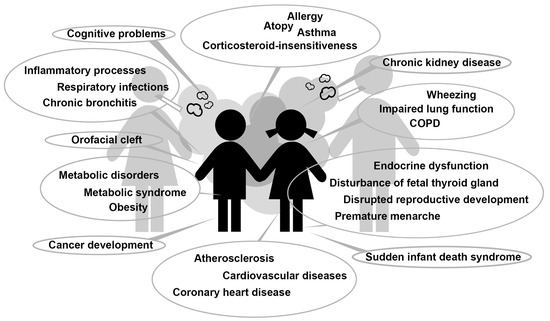

SHS is linked to lots of health hazards. More than 7000 chemicals, including at least 70 carcinogenic substances, have been identified in SHS[3] [3]. These carcinogens can cause several types of cancer (e.g., lung cancer, breast cancer, stomach cancer, cancers of the upper respiratory tract)[6][7] [6,7]. Therefore, SHS increases the risk of children contracting lymphoma, leukaemia, liver cancer or brain tumours[8] [8]. Additionally, SHS is harmful to heart and blood vessels, so it increases the risks of stroke and heart diseases in later life significantly[9] [9]. SHS irritates the airways, can cause or worsen asthmatic diseases and allergies and is a major risk factor in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Tobacco smoke can also trigger lung infections and wheezing in children[10][11] [10,11]. Exposed very young children are at increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome[8] [8]. Not least, SHS seems to be linked with mental health effects[12] [12]. Prenatal tobacco smoke (PTS) exposure can cause poor birth outcomes and pregnancy complications. PTS is linked with biochemical changes in the placenta, leading to alterations to the antioxidant system of the foetus, associated with several adverse health effects both prenatal and postnatal. PTS exposure can lead to pulmonary diseases, e.g., COPD, wheezing, asthma, kidney diseases as well as cardiovascular diseases in later life. Also, metabolic syndrome and obesity can be a consequence of PTS exposure[8][13] [8,13].

Extensive data from epidemiological and experimental studies indicate that gene–environmental interaction during pregnancy and early life can induce permanent changes in physiological processes and disease predisposition by epigenetic mechanisms[14] [14]. The early events during pregnancy and childhood play a key role in the development of the human body. In this vulnerable phase, exposure to tobacco smoke has been shown to have deleterious effects on the development process and may result in permanent damage[15] [15]. The genetic predisposition can lead to substantially aggravated risk for diseases of children exposed to SHS[16][17][18][19] [16–19]. It might be said that PTS is the first major environmental factor that can jeopardise the health of the unborn child (Figure 1)[13] [13].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), data from 2004 from 192 countries showed that 40% of children and about 33% of adult non-smokers were exposed to SHS worldwide[4][20] [4,20]. In the United States, the exposition to SHS in non-smokers decreased from 52.5% from 1999 to 2000 to 25.3% from 2011 to 2012 (SHS exposed children aged 3–11 years: 40.6%)[21] [21]. The European human biomonitoring pilot study (September 2011 to January 2012) reported SHS exposure in children aged 6–11 years from Portugal, Poland, and Romania[22] [22]. Regarding the daily SHS exposure at home, the prevalence in Portugal was 15%, Poland 19.3%, and Romania 21.7%. Each year, more than 1.2 million premature deaths are caused by SHS, 65,000 of which are children. Nevertheless, only 22% of the world population is protected by comprehensive national smoke-free laws[23] [23]. Lau and Celermajer[24] [24] declared in 2014, 50 years after the US Surgeon General’s first report in 1964, that the protection of children from SHS is one of the great healthcare challenges.

Figure 1. Adverse health effects in children induced by second-hand smoke and prenatal tobacco smoke exposure. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.