The Conventional Model of Colorectal Carcinogenesis and the “Serrated” Pathway

Colorectal cancer is a multifactorial and heterogeneous disease

[1]. Most CRCs (75%) are sporadic, whereas about 20% of CRC patients report a family history of the disease. Finally, 3–5% of CRCs are hereditary, with subjects bearing highly penetrant germline mutations that are associated with well-defined cancer-predisposing syndromes such as the hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), best known as Lynch syndrome (1–3%), or the familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) (<1%), or again the hamartomatous polyposis syndrome, which displays the lowest incidence (<0.1%)

[2].

CRC pathogenesis is due to the progressive accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations, some of which being responsible for activating oncogenes or inactivating oncosuppressor genes, that are able to drive the malignant evolution from normal epithelium through early neoplastic lesions (aberrant crypt foci, adenomas, and serrated adenomas) to CRC

[3][4]. Such malignant transformation requires up to 15 years, depending on the characteristics of the lesion and on other independent risk factors such as gender, body weight, body mass index, physical inactivity

[5].

Neoplastic transformation affecting the colon epithelium is characterized by two distinct morphological pathways of carcinogenesis, namely the conventional and the alternative/serrated neoplasia pathways, each one being defined by specific genetic and epigenetic alterations, typical clinical and histological features and leading to different phenotypes

[6][7][8].

The conventional model, the so-called adenoma-carcinoma sequence, is histologically homogeneous and morphologically characterized the adenoma, including tubular or tubulovillous adenoma, as a precursor lesion

[1]. The adenoma-carcinoma sequence is a multistep mutational pathway, in which each histological alteration is the consequence of a molecular dysregulation

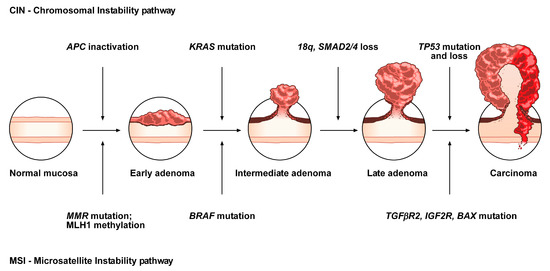

[9][10][11][12]. At the molecular level, this model recognizes a heterogeneous background, based on two mechanisms of tumorigenesis: (i) chromosomal instability (CIN) or (ii) microsatellite instability (MSI)

[13][14][15][16] (

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conventional adenoma-to-carcinoma sequence. The chromosomal instability (CIN) pathway begins with bi-allelic mutations in the tumor suppressor gene APC within the normal colonic mucosa. The latter progressively differentiate into adenocarcinoma upon acquisition of additional mutations in the genes KRAS, SMAD4, and TP53, with consequent dysregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin, MAPK, PI3K and TGF-β signaling pathways. Alternatively, the MSI pathway involves an initial alteration of the Wnt signaling that leads to the formation of an early adenoma. Then, BRAF mutation followed by alterations of the genes TGFBR2, IGF2R, and BAX, participate in the progression toward the intermediate and late stages of carcinogenesis.

CIN represents the most prevalent form of genomic instability. It is detected in 85% of sporadic CRCs and is frequently observed in distal, rather than proximal, colon cancer sites

[15][16]. CIN consists of a gain or loss of all or part of chromosome(s), and is usually associated with mutations in proto-oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes, such as

KRAS or

APC, respectively

[13][16].

MSI occurs in about 15% of CRCs, predicts a favorable outcome in CRC and can also be detected in the serrated pathway

[15][17][18][19]. This genomic instability does not affect chromosomal integrity but consists of an accumulation of insertions/deletions of short nucleotide repeats (microsatellites) that is consecutive to hereditary (5%) or sporadic (10%) alterations in genes involved in DNA mismatch repair (MMR)

[14][15].

Although MSI, according to the National Cancer Institute, is frequently determined using a panel of five markers (BAT25, BAT26, D2S123, D5346, and D17S250), a variety of commercially available panels are currently used in most laboratories

[20]. Depending on the number of microsatellites associated with these markers, tumors have been subclassified into: (i) high, labeled “MSI”, (ii) low, labeled “MSI-L” or (iii) stable, labeled “MSS”

[21]. MSI-L tumors have been regrouped with MSS tumors, due to low differences in their clinicopathological characteristics or in most of their molecular features

[22].

Approximately, 3–15% of all CRCs are represented by sporadic forms with MSI

[21][23]. Several studies have demonstrated that epigenetic hypermethylation (80% of MSI CRCs), and the consequent silencing and inactivation of the gene

MLH1, is the event that triggers malignant transformation and determines a high rate of MSI

[21][23]. Moreover, mutations in MMR genes (20% of MSI CRCs) can also determine MSI tumors, associated with HNPCC (3% of CRCs)

[21][23]. HNPCC is an autosomal dominant disease due to germline mutations in some MMR genes (e.g.,

MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, PMS2, and

PMS1), causing consequent inactivation of the DNA repair system and the accumulation of mutated microsatellites

[24]. In addition, germline deletions in the 3’ end of

EPCAM result in epigenetic inactivation of the adjacent gene

MSH2 and represent another mutational mechanism responsible for HNPCC (1–3% of HNPCC patients)

[25]. HNPCC is not characterized by

MLH1 hypermethylation. Thus, MSI analysis, in addition to

MLH1 evaluation and

BRAF mutation analysis, is currently one of the first steps for the diagnosis of this disease

[24][26].

In contrast to the conventional adenoma-carcinoma pathway, an alternative pathway, featured by the presence of serrated adenomas/polyps as precursor lesions, has been documented over the last 10 years

[21][27][28][29][30][31]. It has been estimated that 15 to 30% of all CRCs arise from early neoplastic serrated lesions. These lesions, that are histologically characterized by a “serrated” (or saw-toothed) appearance of the epithelial glandular crypts within the precursor polyps, have long been considered innocuous

[31][32][33][34]. Nevertheless, serrated lesions are among the main causes of the “interval” CRCs and are associated with synchronous and metachronous advanced colorectal neoplasia

[35][36].

At the molecular level, serrated colorectal lesions rarely present truncating

APC mutations. The majority of CRCs arising from serrated lesions carry

BRAF mutations (whose prevalence varies among the different serrated subtypes), while

KRAS mutations remain less frequent. They are also associated with two pathways, namely MSI and the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), which are involved in genomic instability; the latter being considered as the major mechanism that drives the serrated pathway toward CRC

[37][38].

Although the role of

APC mutations, and the subsequent aberrant activation of the WNT pathway, is fully understood in the conventional adenoma-carcinoma sequence, its role in the serrated pathway remains unclear. To address this issue, the mutational landscape of

APC in serrated precursors and

BRAF mutant cancers has been recently explored

[39]. In the cited study, even if the WNT pathway was notably activated in dysplastic serrated lesions and

BRAF mutant cancers, it was not due to truncating

APC mutations, suggesting the existence of alternative mechanisms of activation of the WNT signaling. Moreover, the role of missense

APC mutations, which are relatively frequent in serrated lesions and

BRAF mutant cancers with MSI, should be further investigated in the serrated pathway.

Overall, CRCs have been classified into five molecular subtypes based on their MSI and CIMP status, among which the three following signatures describe serrated lesions

[21]:

-

CIMP-H, MLH1 methylated, MSI, BRAF mutated lesions, known as sporadic MSI;

-

CIMP-H, MLH1 partially methylated, MSS, BRAF mutated lesions;

-

CIMP-L, MGMT methylated, MSS, KRAS mutated lesions.

2. Histopathological and Endoscopic Features of Serrated Colorectal Lesions

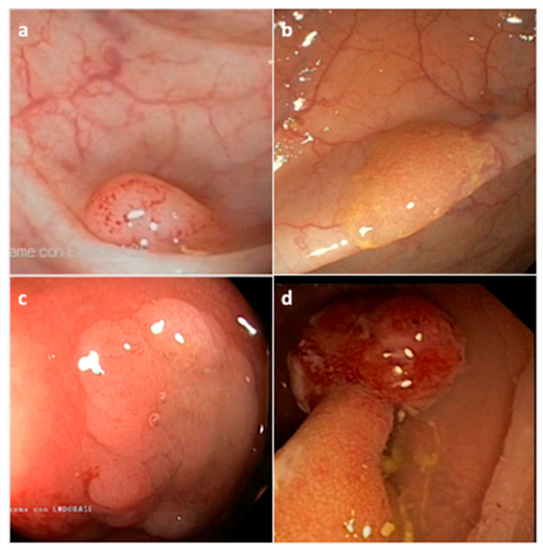

Serrated neoplasia of the colorectum represents one of the CRC subtypes

[40]. They are histologically classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) into three morphological categories: (i) hyperplastic polyp (HP), (ii) sessile serrated adenoma/polyp (SSA/P) with or without cytological dysplasia (SSAD), and (iii) the traditional serrated adenoma/polyp (TSA) (

Figure 2) (

Table 1)

[41]. The serrated subtypes, identified by their cytological characteristics and lesion area, have a distinct endoscopic appearance, share some histological features, and are unique at the biological and molecular levels

[34][42].

Figure 2. Representative endoscopic appearance of serrated lesions of the colorectum. (a) Hyperplastic polyp; (b) Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp; (c) Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp with dysplasia; (d) Traditional serrated adenoma. (Courtesy of Prof. Dr. Giovanni D. De Palma, University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy).

Table 1. Morphologic categories and features of serrated colorectal lesions.

| Histological Classification |

Frequency (%) * |

Location |

Shape |

Mucin Type |

Size |

| Hyperplastic polyp (HP) |

80–90% |

Distal |

Sessile, Flat |

Variable |

<5 mm |

| Microvesicular HP (MVHP) |

60% |

Distal |

Sessile |

Microvesicular |

<5 mm |

| Goblet cell HP (GCHP) |

30% |

Distal |

Sessile |

Goblet cells |

<5 mm |

| Mucin poor HP (MPHP) |

10% |

Distal |

Sessile |

Poor |

<5 mm |

| Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp (SSA/P) |

15–20% |

Proximal |

Sessile/Flat |

Microvesicular |

>5 mm |

| Traditional serrated polyp (TSA) |

1–6% |

Distal |

Sessile/Pedunculated |

Not present |

>5 mm |

HP precursor lesions are the most frequent polyps (80–90%) and mostly remain benign (

Figure 2a) (

Table 1)

[43]. HPs may be flat or sessile, are preferentially located in the distal colon, show a smaller size (< 5mm) than other subtypes, and remain hardly detectable by endoscopic exam. Based on the epithelial mucin content, HP lesions can be histologically subclassified into microvesicular HP (MVHP), goblet cell HP (GCHP), and mucin poor HP (MPHP) polyps (

Table 1)

[28][30][34]. Although the frequency of each HP subtypes is variable, MVHPs are the most common, while MPHPs are the rarest form of HPs

[44][45].

SSA/Ps, which account for 15 to 20% of all serrated polyps, especially develop in the proximal colon, are pale lesions that can be either sessile or flat, with a variable size usually larger than 5 mm in diameter (

Figure 2b) (

Table 1)

[43][46][47]. SSA/Ps can develop either as primary tumors or evolve from hyperplastic polyps. SSA/Ps lesions cannot be easily distinguished from MVHPs, however, MVHPs larger than 10 mm in diameter can be considered clinically equivalent to SSA/Ps. Additionally, SSA/Ps can be subclassified according to the absence or presence of dysplasia (SSAD); the latter being detected in about 0.20% of all serrated lesions (

Figure 2c)

[46]. Overall, by combining both serrated and dysplastic features, SSADs consist of advanced lesions that usually evolve rapidly toward carcinoma.

TSA lesions are the rarest form of colorectal serrated polyps (1–6%) (

Figure 2d) (

Table 1)

[34][43]. TSAs, that arise either from HPs or SSA/Ps, are precancerous sessile or, more often, pedunculated polypoid lesions, which preferentially develop in the distal colon and rectum, and show a larger size (>5 mm) than HPs

[45]. A less aggressive variant form of TSA is the filiform serrated adenoma

[48]. TSA can also be subclassified according to the presence of dysplasia that can be of two types: the well-known “adenomatous dysplasia” and the less frequently observed “serrated dysplasia”, which is related to the serrated pathway. The latter can be graded as low- or high-grade dysplasia depending on the absence or presence of cytological and architectural atypia, respectively. Recently, it has also been evidenced that TSA can co-exist with other lesions such as HPs, SSA/Ps and tubulovillous adenomas

[49]. Usually, only TSA with serrated dysplasia develops into invasive carcinomas.

However, alternative molecular classifications have been proposed based on recent findings, such as those defined by the CRC Subtyping Consortium (CRCSC) or by Fennell et al.

[50][51][52].

The heterogeneity of serrated lesions and the presence of morphological features shared with different subtypes, make difficult the accurate CRC classification during the diagnostic process and also the physiopathological interpretation of the observed lesions. In addition, serrated lesions with a distinctive endoscopic appearance are more difficult to detect compared to conventional lesions. In fact, detection of serrated lesions, particularly those located in the proximal colon, is difficult and endoscopist-dependent

[53][54]. Therefore, characterization of molecular markers specific for each CRC subtype may improve the identification of CRCs arising from this alternative pathway, and consequently support the diagnostic process as well as the clinical decision-making.

3. Molecular Features of the Serrated Colorectal Precursor Lesions

3.1. Hyperplastic Polyps

As described above, hyperplastic polyps can be histologically subclassified into MPHP, GCHP and MVHP lesions (Table 1). The endoscopic diagnosis between these subtypes, and furthermore between HPs and SSA/Ps, is difficult and may be supported by the detection of specific biomarkers.

MPHP is the rarest form of HP and is not well described; in fact, to date, it has only been associated with CIMP-H (

Table 3). MVHP and GCHP are the most common HP subtypes. At the molecular level, MVHP is particularly characterized by

BRAF V600E mutation and CIMP-H (

Table 3); for that reason, it is considered a precursor of SSA/Ps

[17][55].

Table 3. Molecular profile of serrated colorectal lesions.

| Serrated Lesion |

BRAF/KRAS Status |

CIMP Rate |

Gene Methylation |

MSI Rate |

| HP |

BRAF mutated |

CIMP-H |

MLH1 not methylated |

MSS |

| MPHP * |

controversial |

CIMP-H |

controversial |

controversial |

| GCHP * |

KRAS mutated |

CIMP-L |

MLH1 not methylated |

MSS |

| MVHP * |

BRAF mutated |

CIMP-H |

MLH1 not methylated |

MSS |

| SSA/P |

BRAF mutated |

CIMP-H |

MLH1 not methylated |

MSS |

| SSAD |

BRAF mutated |

CIMP-H |

MLH1 hypermethylated |

MSI |

| TSA |

KRAS/BRAF mutated or neither |

CIMP-L/-H |

MLH1 not methylated |

MSS |

| TSA HGD |

KRAS mutated |

CIMP-L |

MGMT hypermethylated |

MSS |

GCHP is linked to

KRAS mutations (often missense substitutions at glycine codons 12 or 13) and CIMP-L (

Table 3)

[19][56]. Mutations in

BRAF or

KRAS, that rarely coexist in CRC, constitutively activate the MAPK signaling pathway, which is involved in the regulation of several cellular processes, and inhibit the apoptosis mechanism, thus supporting tumor cell proliferation.

To shed light on other molecular features of HP lesions, early markers of potentially malignant serrated precursor lesions have been identified, such as

MUC5AC [57][58]. MVHP and SSA/P lesions present an hypomethylated

MUC5AC when compared to GCHPs. Interestingly, this gene hypomethylation occurs early in the serrated pathway, gradually increasing from MVHP to SSA and SSAD, and is particularly related to lesions with

BRAF mutations, CIMP-H and MSI. Thus, the epigenetic alteration of

MUC5AC could be a potential marker to evaluate the malignant evolution of serrated precursor polyps.

3.2. Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyps

At the molecular level, SSA/Ps are mainly characterized by

BRAF mutations, MSS, CIMP-H and unmethylated

MLH1 (

Table 3)

[17][59]. Other molecular characteristics of sessile serrated lesions, as well as a subtype-specific gene signature, have been explored and, in some cases, identified based on epigenetic and transcriptomic approaches. An example is the recent molecular characterization of SSA/Ps in a large African American cohort, in which the over-expression of

FSCN1 and

TRNP1 seemed to segregate with race

[60].

The formation of SSA/Ps has been associated with the tumor suppressor gene

SLIT2, who is down-expressed in SSA/Ps compared to TSAs/adenomas/normal tissues as a result of promoter hypermethylation and loss of heterozygosity

[61]. The high rate of

SFRP4 methylation in SSA/P compared to the corresponding adenoma series has also been evidenced

[59].

CTSE,

TFF1 and

ANXA10 were identified as potential clinical markers of SSA/P lesions

[62][63][64]. In particular, ANXA10 expression levels significantly increased at the gene and protein levels in SSA/Ps in comparison to MVHPs

[63][65].

Hes-1, a downstream target of the Notch signaling pathway which involved in intestinal development, has also been described as a SSA/P-specific biomarker due to its immunohistochemical (IHC) loss of expression in SSA/Ps compared to HPs or normal colonic mucosa

[66].

In a large-scale study, differentially expressed genes and immunohistochemical markers were also identified when comparing SSA/Ps to controls

[67]. In particular, among the 1294 genes identified,

VSIG1 and

MUC17, were uniquely and significantly increased in SSA/Ps with respect to controls/HPs/adenomas, thus evidencing a molecular signature specific of the polyps and the involvement of different molecular pathways across distinct CRC lesions.

Recently, a platform-independent approach was adopted in order to differentiate SSA/P from HP lesions

[68]. SSA/Ps have been characterized by a specific molecular profile of up-/down-regulated genes involved in the inflammatory process, immune response, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), extracellular matrix (ECM) interaction, cell migration and cell growth. This profile defines the malignant potential of SSA/P lesions and allow to distinguish them from HPs.

As for MVHP polyps, SSA/P immunohistochemically expresses MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC6

[57][69]. The role of MUC6 was evaluated in SSA/Ps lesions and is controversial

[57]. Nevertheless, MUC6 was assessed to be a supportive immunohistochemical marker to differentiate SSA/Ps from TSAs

[70][71].

3.3. Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyps with Dysplasia

The main molecular characteristics found in SSADs are

BRAF mutations, a nuclear β-catenin accumulation, CIMP-H and MSI as a consequence of

MLH1 gene silencing due to promoter hypermethylation (

Table 3)

[72]. Although the loss of

MLH1 expression is related to the development of dysplasia,

MLH1 inactivation can also be detected in SSA/P non-dysplastic crypts, indicating the putative biomarker role of

MLH1 in predicting dysplastic progression of these polyps

[73].

Moreover, it has been demonstrated that SSAD lesions can be also associated with MSI, harboring different genetic alterations

[72]. In particular, MSI lesions are characterized by a high mutational rate of

FBXW7 and the loss of

MLH1 expression, while MSSs display

TP53 mutations without

FBXW7 mutations. Thus,

FBXW7 alterations can be correlated to the progression of MSI serrated lesions in CRC.

SSAD polyps, and particularly the progression of SSA/P lesions toward dysplasia, can also be characterized by alterations in WNT signaling-associated genes like protein-truncating mutations of

RNF43,

APC,

ZNRF3 and the hypermethylation of

AXIN2 and

MCC [72][74][75][76]. Furthermore, frameshift mutations in

RNF43 are frequently present in patients with

MLH1-deficient SSA/P with dysplasia

[74].

Genetic variants of DNA-regulatory elements, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), can influence gene expression and be associated with cancer risk. An example is the well-known CRC-associated rs1800734, or MLH1-93G>A, which can be detected in the promoter region of

MLH1. This SNP enhances

DCLK3 expression which in turn promotes CRC development

[77]. MLH1–93 G/a polymorphism has been significantly associated with

MLH1 hypermethylation in SSAD lesions compared to TSAs, and represents a putative risk factor for

MLH1 promoter methylation

[78].

3.4. Traditional Serrated Adenoma/Polyps with and without Dysplasia

TSA is an enigmatic subtype due to its heterogeneous molecular features

[49][79]. TSAs can harbor

KRAS or

BRAF mutations, or neither, and can be CIMP-low or high, and MSS (

Table 3)

[80]. In contrast with SSA/Ps, TSA lesions do not show

MLH1 promoter hypermethylation but can present

MGMT hypermethylation (

Table 3)

[81]. Evaluation of the mutational status of WNT genes in TSA lesions has identified precursor- and TSA-specific alterations that elucidate the mechanism involved in the genetic transition from precursor polyps to TSAs

[82]. PTPRK-RSPO3 fusion and mutations in

PTEN,

RNF43,

APC, or

CTNNB1 are genetic features of TSAs

[83][84].

Several epigenetic biomarkers have also been associated with TSA. An example is

SMOC1 which is down-expressed, due to methylations in its promoter region, in TSAs as compared to SSA/Ps

[85]. In particular,

SMOC1 methylation increases during TSA development and has been correlated with

KRAS mutation and CIMP-L. In addition, low expression of the SMOC1 protein in TSA can be verified by IHC assay, supporting its exploitation as a TSA-specific diagnostic biomarker.

The transition of TSAs toward dysplasia is characterized by nuclear β-catenin accumulation,

TP53 mutation and

p16 inactivation, as detailed below

[21]. TSA-HGDs are usually characterized by CIMP-H,

BRAF mutations and MSS (

Table 3). The high rate of differentially methylated region in the promoter P0 of

IGF2 gene (IGF2 DMR0) and hypomethylation of

LINE-1 are two epigenetic biomarkers of TSA-HGD

[86].

LINE-1 hypomethylation in CRC has been associated with early age onset and family history of CRC. In several studies,

LINE-1 hypomethylation has been inversely correlated with MSI and CIMP-H phenotypes. Interestingly, the methylation level of

LINE-1 has recently been assessed from plasma-circulating cell-free DNA, thus comforting a putative role as a preventive biomarker in CRC

[87][88].