1000/1000

Hot

Most Recent

Nanomaterials are defined as materials that contain particles measuring between 1.0 and 100 nm in at least one dimension.

During the past few decades, numerous treatment methods have been developed to deal with heavy metal contamination, including physical methods, such as adsorption, coagulation, evaporation, and filtration; chemical methods, such as chemical precipitation, oxidation, ion exchange, and electrochemical processes; and biological methods, such as biodegradation and phytoremediation [1][2][3][4]. However, most of these treatment methods have significant drawbacks, such as high costs, complexity of operation, and secondary pollution [5][6][7]. For instance, despite the great removal efficiency of chemical precipitation, its installation cost is quite high [8]. Of all of the known methods, adsorption is widely used because of its low cost, high removal efficiency, strong practicality, high applicability, and good operability [9][10].

Absorbency is a key factor of the adsorption method. Therefore, it is crucial to select the most suitable adsorption material. A good adsorbent should have the advantages of a large specific surface, great sorption sites, diverse surface interactions, fast adsorption rates, and low costs [11][12][13]. Currently, the most commonly used adsorbents are biochar, activated carbon, carbon film, biopolymers, clay materials, and nanomaterials [14][15][16].

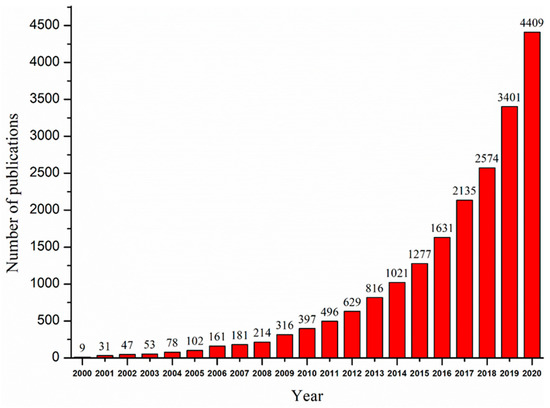

Nanomaterials are defined as materials that contain particles measuring between 1.0 and 100 nm in at least one dimension [17][18]. Since the emergence of nanomaterials in the 1970s, an increasing number of researchers have focused on the application of nanomaterials in removing pollutants, such as heavy metals, organic pollutants, and pathogens, from contaminated surface waters, groundwater, sediments, and soil [16][19][20]. Nanomaterials are promising adsorbents and catalysts for the application of environmental remediation because of their great chemical reactivity, large adsorption surface, low temperature modification, and active atomicity [21][22]. The small size of nanoparticles makes it easier for the atoms at the surface to adsorb and have reactions with other atoms in order to achieve charge stabilization [23]. The large specific surface area can greatly improve the adsorption capacities of adsorbents [18][24]. In addition, because of the reduced size, nanomaterials have surfaces that are very reactive [25]. Not only can they efficiently adsorb pollutants, but they also have unique redox properties that are beneficial for the removal of redox-sensitive pollutants via degradation [17][26]. Studies on the removal of heavy metals using nanomaterials are of increasing importance and academic interest, as can be seen from the number of papers published every year, as shown in Figure 1. However, some of the commonly used nanomaterials do have limitations, including high costs, potential toxicity, difficulty in recycling, and an easy interaction with other media [5]. Even though nanomaterials have been widely studied in the field of heavy metal remediation, a comprehensive and systematic review of the application of nanomaterials for the removal of heavy metal ions is relatively lacking.

Figure 1. Trend of published papers on nanomaterials for removing heavy metals. Obtained from ScienceDirect. Search words (nanomaterials; heavy metal).

Nanomaterials are classified into carbon-based nanomaterials and inorganic nanomaterials [27]. They have been widely applied in the field of environmental remediation. Among them, nano zero-valent iron (NZVI), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) are the most frequently used and studied nanomaterials [28][29]. Table 1 summarizes the applications and the performance highlights of nanomaterials for removing heavy metals from water and soil environments.

Table 1. Applications of nanomaterials in removing heavy metals from the environment.

| Types of Nanomaterials | Environment | Target Heavy Metals | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| NZVI-HCS | Water | Pb(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II) | The maximum adsorption capacities were 195.1, 161.9, and 109.7 mg·g−1 for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II), respectively |

| NZVI | Sediment | Cd(II) | The maximum adsorption capacity of for Cd(II) was 769.2 mg g−1 at 297 K |

| BC-NZVI | Water | Cr(VI) | The performance of BC-NZVI was pH dependent, with a maximum Cr(VI) removal efficiency of 98.71% at pH 2 |

| BC-NZVI | Soil | Cr(VI) | The immobilization efficiency of Cr(VI) and total Cr reached 100% and 92.9%, respectively, when 8 g kg−1 of BC-NZVI was applied for 15 d |

| NZVI | Water | Pb(II) | The maximum adsorption capacity of NZVI was 807.23mg·g−1 at pH 6 |

| OA-NZVI | Soil | Cd(II), Pb(II), and Zn(II) | The highest Cd, Pb, and Zn removal efficiencies were 46.66%, 48.88% and 47.01%, respectively, for farmland soil at the NZVI concentration of 0.4 g L−1 |

| MWCNTs | Water | Zn(II) | The maximum adsorption efficiency was 96.27% at pH 5 for 6 h |

| MWCNTs-COOH | Water | Hg(II) and As(III) | The maximum removal efficiencies for Hg(II) and As(III) were 80.5% and 72.4% at the adsorbent dose of 20 mg L−1 and pH 7.6–7.9, respectively |

| CNTs | Water | Zn(II) | The maximum adsorption capacities of Zn(II) were 43.66 and 32.68 mg g−1 by SWCNTs and MWCNTs, respectively |

| TiO2-NCH | Water | Cd(II) and Cu(II) | The maximum adsorption efficiency of Cu(II) and Cd(II) from wastewater samples were 88.01% and 70.67%, respectively |

| Mesoporous carbonated TiO2 NPs |

Water | Sr(II) | The maximum adsorption capacity of Sr(II) 204.4 mg g−1 at the natural pH by 4C-TiO2 |

| TiO2 NPs | Soil | Cd(II) | The greatest Cd accumulation capacity of Trifolium repens reached 1235 µg pot−1 with PGPR + 500 mg kg−1 TiO2 NPs treatment |

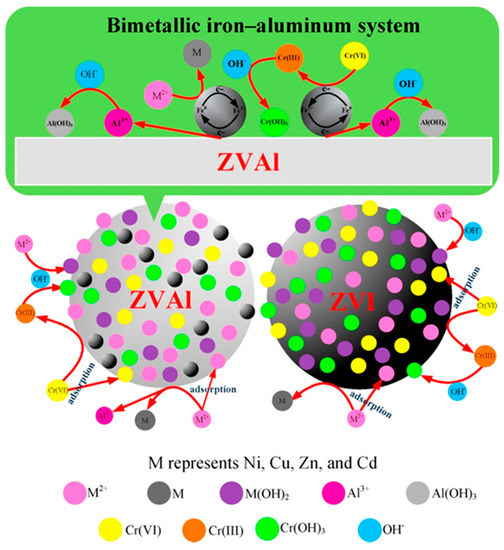

NZVI is the most widely studied and applied nanomaterial in environmental remediation and has been proven to be an effective adsorbent, reductant, and catalyst for a variety of contaminants, such as heavy metal ions, halogenated organic compounds, organic dyes, and pharmaceuticals [35][36][37]. NZVI has a typical core shell structure generated during the synthesis process that contains a shell of Fe(II), Fe(III), and zero-valent iron [42]. As a result of the unique structure, NZVI has the abilities of reduction, surface sorption, stabilization, and precipitation of various contaminants [54,55,56]. Several studies have reported that NZVI exhibited excellent performance for removing heavy metal(loid) ions from contaminated environments [30][31][32][33]. For instance, Yang et al. [30] applied a corn stalk-derived, biochar-supported NZVI for the removal of heavy metal ions from water. The results showed that the equilibrium adsorption capacities reached 195.1, 161.9, and 109.7 mg·g−1 for Pb(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II) after 6 h, respectively. Boparai et al. [31] reported that NZVI could be applied as an efficient adsorbent to remove cadmium from contaminated water. The maximum adsorption capacity of NZVI for Cd(II) was 769.2 mg g−1, which was achieved at a temperature of 297 K. Su et al. [33] found that the immobilization efficiency of Cr(VI) reached 100% when 8 g kg−1 of biochar-supported NZVI was applied in hexavalent chromium-contaminated soil for 15 days. Acid mine water was treated using NZVI, and this resulted in a significant decrease in the concentrations of microcontaminants, such as U, V, As, Cr, Cu, Cd, Ni, and Zn [46]. Huang et al. [47] investigated the effects of different dosages of NZVI on plant growth and the Pb accumulation of Lolium perenne. The Pb accumulation and plant biomass were significantly enhanced when the NZVI and Pb accumulation in L. perenne reached a maximum of 1175.40μg per pot with the treatment of 100 mg kg−1 NZVI. Vítková et al. [48] reported that NZVI application significantly stabilized the As and Zn in As-rich and Zn-rich soils by the formation of Fe (hydr)oxides. Han et al. [49] investigated the removal efficiency of permeable reactive barriers (PRBs) filled with zero-valent iron (ZVI) and zero-valent aluminum (ZVAl) as a reactive medium and discussed the reaction mechanism of Cr(VI), Cd(II), Ni(II), Cu(II), and Zn(II) with ZVI/ZVAl. The main possible mechanisms were adsorption, formation of metal hydroxide precipitates, and reduction, which are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Removal mechanisms of five heavy metal ions by zero-valent iron/zero-valent aluminum (ZVI/ZVAl). Reproduced with permission from ref 60 published by Elsevier, 2016.

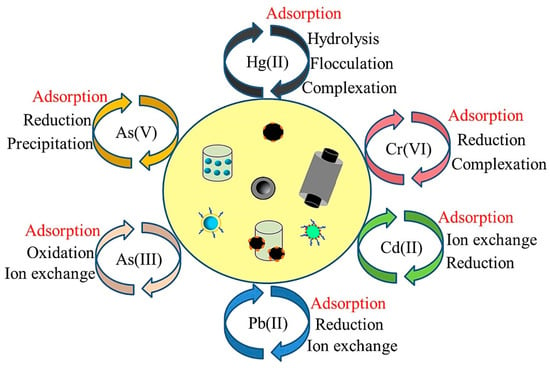

CNTs, which were first discovered in 1991, have a unique chemical structure that consists of a graphitic sheet rolled up in a cylindrical shape [50][51]. CNTs are very strong materials that are over 100 times more resistant and six times lighter than steel [52]. Depending on the number of cylindrical shells, CNTs are classified into two categories: single wall CNTs (SWCNTs) and multi-wall CNTs (MWCNTs). Because of their extraordinary characteristics, such as a large specific surface area, unique morphology, and high reactivity, CNTs are considered to be an excellent nanomaterial for the removal of various organic and inorganic pollutants [53][54]. CNTs can be produced via methods such as chemical vapor deposition, laser ablation, and arc discharge. The adsorption capacity of CNTs is greatly affected by the methods by which they are synthesized with different reactants and catalysts [55]. For instance, Mubarak et al. [56] studied the effect of microwave-assisted MWCNTs on the removal of Zn(II) from wastewater. The results showed that the highest removal rate (99.9%) was achieved at pH 10 and a CNTs dosage of 0.05 g. Sun et al. [57] found that the removal efficiency of Cd(II) by CNTs increased at pH 3. Osman et al. [58] reported that CNTs synthesized from potato peel-waste material removed up to 84% of Pb(II) within 1 h of the CNTs’ application. Yaghmaeian et al. [59] used MWCNTs as a sorbent to remove Hg(II) from wastewater. The results showed that an adsorption capacity of 25.64 mg g−1 and a removal rate of greater than 85% were achieved when operated at 25 °C, pH 7, with a contact time of 120 min. Sobhanardakani et al. [60] prepared oxidized MWCNTs and used it as an adsorbent for the removal of Cu(II) from an aqueous solution. The maximum removal rate for Cu(II) was 99.5% at the optimum temperature (25 °C) and the most suitable pH value (6.0). There may be various pathways for heavy metal removal by CNTs, including adsorption, electrostatic interaction, reduction, and ion exchange, depending on the novel properties provided by functionalization and the heavy metal ions (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The mechanisms of removing heavy metal from an aqueous environment by carbon nanotubes (CNTs). Reproduced with permission from ref [61] published by Elsevier, 2018.

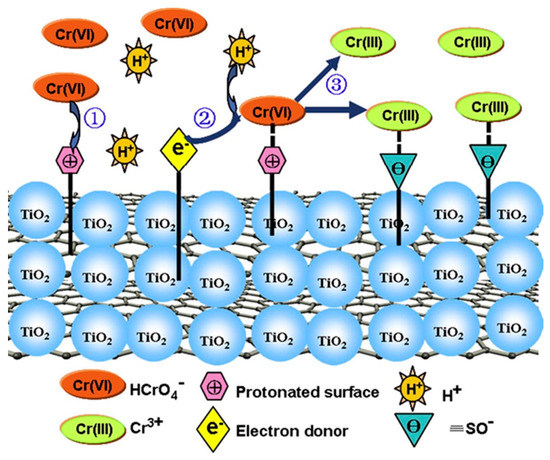

Among the nanomaterials used for environmental remediation, TiO2 NPs have been extensively studied [62]. TiO2 NPs show good abilities for photocatalysis, high reactivity, and chemical stability, and they have been successfully applied for modifying the mobility and toxicity of heavy metals in water, soil, and sediment [63][64]. In addition, another advantage of TiO2 NPs is their ease of synthesis. Goutam et al. [65] synthesized TiO2 NPs using a leaf extract and used it to treat tannery wastewater. The results showed that 76.48% of the Cr was removed from the wastewater using green-synthesized TiO2 NPs. Mahmoud et al. [66] reported that the microwave-synthesized TiO2 NPs bonded with the chitosan nanolayer and removed 88.01% of the Cu (II) and 70.67% of the Cd (II) from wastewater when the pH value was 7.0. Gebru et al. [67] synthesized cellulose acetate (CA)/TiO2 NPs using a new electrospinning technique and tested its adsorption capacity for removing Pb(II) and Cu(II) ions from water. The CA/TiO2 adsorbent removed 99.7% and 98.9% of Pb(II) and Cu(II) ions under the most optimized conditions. Fan et al. [68] reported that the concentrations of exchangeable, carbonate, and iron-manganese oxide of As and Pb in the sediments decreased with an increasing amount of TiO2 NPs. Singh and Lee [69] investigated the effect of TiO2 NPs on Cd phytoremediation in Glycine max. The results showed that the Cd accumulation in the aerial portions of the plants increased by approximately 2.6 times when 300 mg kg−1 TiO2 NPs were added to the soil. Zhao et al. [70] proposed the possible removal mechanisms of Cr(VI) by reduced graphene oxide decorated with TiO2 NPs (TiO2-RGO), which is shown in Figure 4. It was speculated that the negatively charged Cr(VI) was bound to the surface of TiO2-RGO, which had a positive charge and was reduced to Cr(III). Then, the Cr(III) species was released into the solution due to electrostatic repulsion with the surface of TiO2-RGO.

Figure 4. The possible mechanism of Cr(VI) reduction by TiO2-RGO. Reproduced with permission from ref 81 published by Elsevier, 2013.