1000/1000

Hot

Most Recent

Radiation-balanced lasers can provide lasing without detrimental heating of laser medium. This new approach to the design of optically pumped rare-earth (RE)-doped solid-state lasers is provided by balancing the spontaneous and stimulated emission within the laser medium. It is based on the principle of anti-Stokes fluorescence cooling of RE-doped low-phonon solids.

The replacement of flash lamps by laser-diode pumping for solid-state lasers has brought a very important breakthrough in the laser technology, in particular for high-power lasers [1][2]. Compared to flash-lamp pumps, laser diodes have led to a significant benefit in efficiency, simplicity, compactness, reliability, and cost. At the same time the thermal problem has come into existence for high power lasers. Special care concerning thermal management is necessary to develop efficient high-power lasers.

To solve the thermal problem, the classical rod solid-state laser medium design has been replaced by new approaches including fibre lasers [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9], slab lasers [10][11], and thin-disk lasers [12][13]. The very high surface-to-volume ratio and optical guidance have provided tremendous progress in the power scalability of high-power lasers.

In 1999, Bowman [14] proposed a radiation-balanced (athermal) rare-earth (RE)-doped bulk laser, which operates without internal heating. In this laser, all photons generated in the laser cycle are annihilated with the cooling cycle, that is, the heat generated from stimulated emission is offset by cooling from anti-Stokes emission. Athermal lasers, which are free from all thermal effects, provide a tremendous potential for an increase in the output power, maintaining a high-quality output laser beam. Beginning in 1999, several kinds of radiation-balanced lasers, including fibre lasers, disk lasers, and microlasers, have been proposed and developed. Some of these lasers have been discussed in [15][16].

The idea to remove the thermal energy from a system optically using anti-Stokes fluorescence was proposed by Pringsheim in 1929 [17]. In 1995, laser cooling with anti-Stokes fluorescence was demonstrated for RE-doped solids [18]. In this first proof-of-principle experiment, a high-purity ytterbium (Yb3+)-doped fluorozirconate ZrF4–BaF2–LaF3–AlF3–NaF–PbF2 (ZBLANP) glass sample was cooled down to only 0.3 K below room temperature.

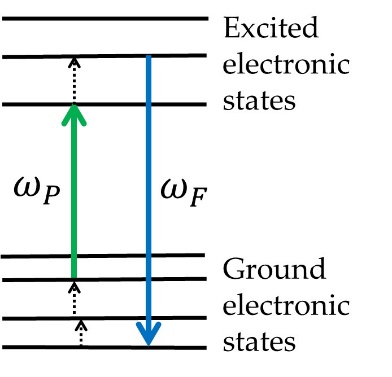

Each energy level of the RE ions doped into the crystal or glass host splits into a set of sublevels as a result of the Stark effect. These sets of sublevels are known as Stark level manifolds. In order to realize cooling with anti-Stokes fluorescence in an RE-doped sample, electrons must be excited from the top of the ground manifold to the bottom of the excited manifold of the RE ions. This implies that the pump wavelength, λP=2πc⁄ωP, must be in the long wavelength tail of the absorption spectrum. After thermalization accompanied by phonon absorption, anti-Stokes fluorescence photons remove energy from the system (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Energy levels and relevant excitation and decay processes for the laser-cooled RE-doped sample. ωP and ωF are the pump and the mean fluorescence frequencies, respectively.

The efficiency of laser cooling can be estimated as a difference between the energy of the mean fluorescence photon, ℏωF, and the energy of the pump photon, ℏωP, normalized by the energy of the pump photon [19]:

![]()

where ωP and λP are the frequency and the wavelength of the pump photon, respectively.

where λF and ωF are the mean fluorescence wavelength and the mean fluorescence frequency, respectively. IF (λ) is the fluorescence intensity at the wavelength λ.

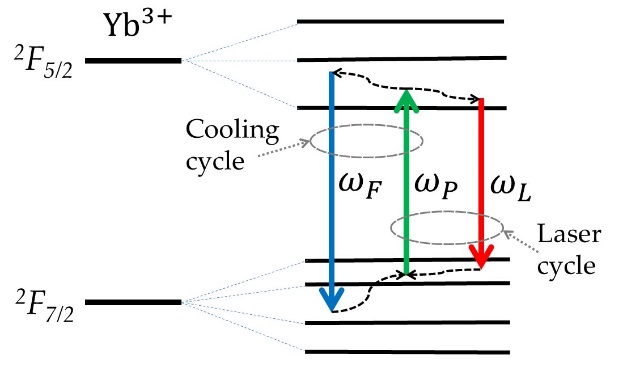

Let us consider the basic concepts of a radiation-balanced (athermal) laser. A solid-state laser of this type can be often referred to as a quasi-three-level laser. The population of each sublevel within a manifold is described by Boltzmann occupation factors. We assume that transitions between these sublevels are purely nonradiative transitions, provided by phonon absorption and emission. This process takes place on a picosecond timescale and is known as thermalization. Let us consider an isotropic laser medium with the total density of the active ions NT. Optical transitions can occur between the ground manifold and the first excited manifolds, giving rise to overlapping, thermally broadened absorption and emission spectra. These spectra are characterized by absorption, σa (λ,T), and emission, σe (λ,T), cross sections, respectively. They depend on a wavelength, λ, and a temperature, T. For radiation-balanced operation of a laser, the mean fluorescence frequency and the pump and laser frequencies must satisfy the following relation: ωF>ωP>ωL(Figure 2). In this case, the system includes two cycles: the laser cycle and the cooling cycle. The laser cycle includes the pump and laser photons at the frequencies ωP and ωL, respectively. It is accompanied by phonon generation. The cooling cycle can be considered as a cycle including the pump photon and the mean fluorescence photon at the frequencies ωP and ωF, respectively. It is accompanied by phonon absorption.

Figure 2. Energy diagram of an Yb3+-doped radiation-balanced laser. ωP and ωL are the pump and laser frequencies, respectively. ωF is the mean fluorescence frequency.

We assume that a bandgap between the excited and ground manifolds is large compared to the energies of the phonons. As a result, the transitions between the excited and ground manifolds are purely radiative. We also assume the absence of excited-state absorption, energy transfer, radiative trapping, and background absorption. In this case, the rate equation takes the form:

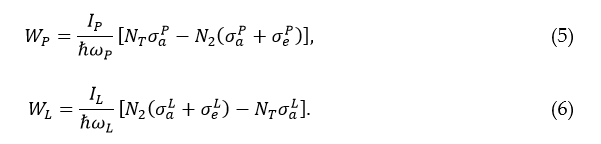

where N1 is the population of the ground manifold and N2 is the population of the excited manifold. The last term in Equation (3) describes the total spontaneous decay rate of the upper manifold. WP is a pump rate, and WL is the stimulated emission rate:

Here IP and IL are the intensities of the pump beam and the laser signal, respectively. ![]() and

and ![]() are the absorption (a) and emission (e) cross sections at the pump (P) wavelength, λP, and at the laser (L) wavelength, λL, respectively.

are the absorption (a) and emission (e) cross sections at the pump (P) wavelength, λP, and at the laser (L) wavelength, λL, respectively.

Following the law of conservation of energy, one can estimate heat generated in the laser medium. Indeed, the difference between the absorbed power density and the emitted power density must be equal to the local generated heat power density:

Substituting Equations (3)–(6) into Equation (7), one can calculate the heat power density generated at any point of the laser medium. Equation (7) for heat power density includes both the pump, IP, and laser, IL, intensities in the laser medium.

If the laser system is in a steady state, dN2⁄dt=0, Equation (3) takes the form

Let us find the relation between the pump and laser beam intensities IP and IL providing athermal operation of the laser, Pheat=0. In this case, Equation (7) becomes

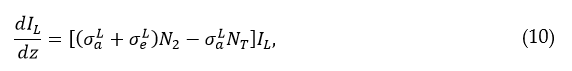

The change in the laser signal intensity along the length of the laser medium can be described by the well-known equation

where z is the coordinate along the length of the laser medium. Substituting Equations (5), (6), (8), and (9) into Equation (10), one can obtain the equation describing the laser signal at any point, z, along the length of the laser medium

where ![]() and

and ![]()

is the saturation intensity of the laser signal. To keep the radiation balance at each point in the laser medium, the pump intensity must be distributed properly along the length of the laser medium following the relation obtained from Equations (8) and (9)

where ![]() and

and ![]()

is the saturation intensity of the pump signal. As one can see in Equation (12), athermal laser operation requires careful control of the pump intensity distribution along the laser medium. Any deviation from this distribution will result to heating or cooling in some parts of the laser medium, which can be estimated with Equation (7). Since iP (z)>0, one can see in Equation (12) that there is a minimum value of laser signal intensity in the laser cavity that can undergo athermal amplification:

A comprehensive theory of the radiation-balanced (athermal) RE-doped bulk solid-state laser was developed in [14]. In [20], it was enhanced for the radiation-balanced (athermal) RE-doped fibre amplifiers.

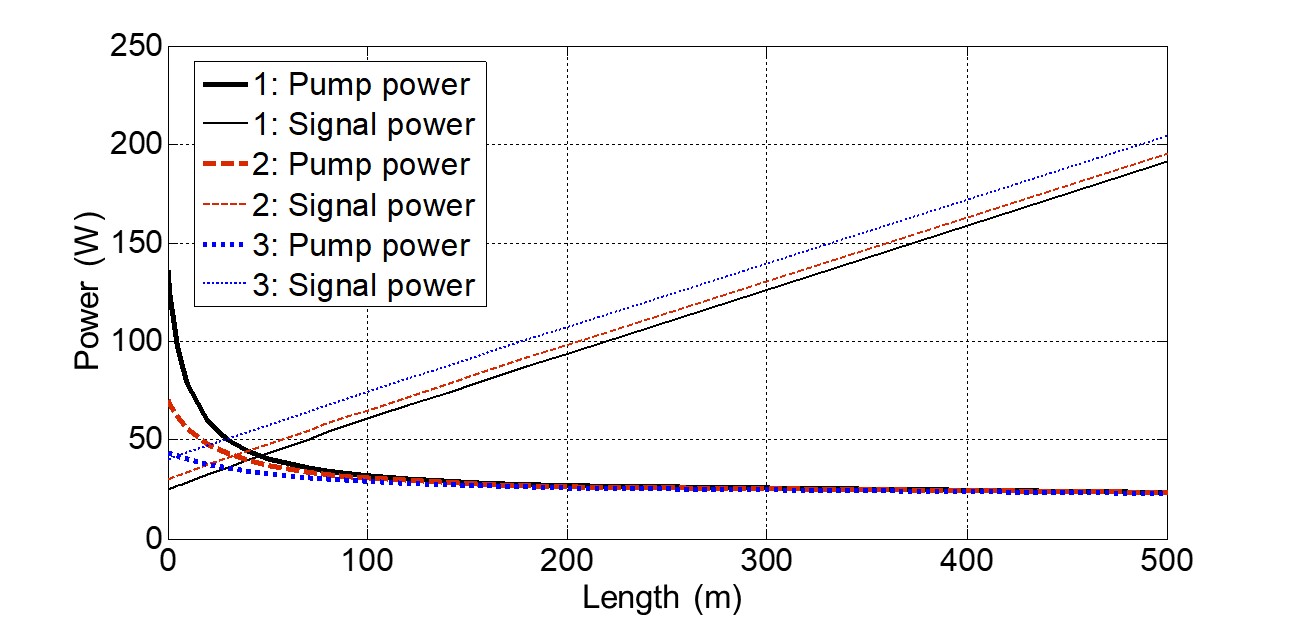

As one can see from the theory, a detailed balance of the stimulated and spontaneous emission at each point of the laser medium can provide a solid-state laser that generates no internal heat. Unfortunately, there are two serious problems associated with the practical development of radiation-balanced amplifiers and lasers: the precise control of the pump power and almost linear growth of the amplified signal (Figure 3). The linear growth of the power of the amplified signal requires an enormous increase in the length of the active medium for very high output power. The athermal bulk or fibre laser requires precision control of the pump power at each point along the length laser medium. This is not a simple problem, especially in the case of a fibre amplifier or laser.

Figure 3. Dependence of the signal and pump powers from the length of the athermal fibre amplifier for three different input signal powers: (1) 25W, (2) 30W, and (3) 40W.

At the present time, athermal lasers follow four main designs: radiation-balanced bulk and fibre lasers, radiation-balanced disk lasers, and athermal microlasers.

Experiments devoted to radiation-balanced lasers began at the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) in 1999 [21]. New materials for laser cooling were investigated. In 2002, the first athermal bulk laser was experimentally demonstrated with an Yb3+:KGd(WO4)2 crystal [22]. The laser design based on direct diode pumping of Yb3+:KGd(WO4)2 crystals was developed further in [23].

In 2021, the first radiation-balanced silica fibre amplifier was demonstrated. An Yb3+-doped silica fibre served as an active medium [24]. The core diameter of the silica fibre was 21 μm. Its numerical aperture was 0.13. The Yb3+ concentration was 2.52 wt.%. The fibre was codoped with 2.00 wt.% Al to reduce concentration quenching. The wavelength of the pump was 1040 nm and the signal wavelength was 1064 nm. The mean fluorescence wavelength of Yb3+ was 1003.9 nm and the radiative and quenching lifetimes were 765 μs and 38 ms, respectively.

In 2000, an Yb3+:KGW laser disk was edge-pumped with radially focused laser diode bars [25]. It generated up to 490 W. In 2019, the radiation-balanced Yb3+:YAG disk laser was experimentally demonstrated in an intracavity pumping geometry [26]. An optically pumped vertical-external-cavity surface-emitting laser (VECSEL) was used to enhance the pump absorption. The broad tunability and good beam quality of VECSELs provided additional parametrical freedom. Recently, Yb3+:YLF and Yb3+:LLF laser disks have been investigated in external multipass pumping schemes [27][28]. Compared to intracavity pumping, external multipass pumping offers higher control on pump spot size and mode-matching conditions. LLF is an isomorph of YLF. They have very similar thermo-optics properties. The Yb3+:YLF and Yb3+:LLF laser disks with the Yb3+ concentration of 10%, 1 mm thick, and 5 mm diameter were pumped at the wavelength 1020 nm corresponding to the lowest energy transition between ground and excited manifolds of Yb3+ ions. This wavelength is convenient for the system cooling. Laser emission was observed around 1050 nm.

The radiation-balanced version of the spherical microlaser was proposed in [29]. In this athermal microlaser the monolayer of upconverting nanoparticles (UCNPs) was deposited on the surface of the microsphere. This monolayer consists of two different UCNPs: Yb3+-doped β-NaYF4 UCNPs, which are responsible for optical refrigeration, and Yb3+/Er3+/Tm3+-codoped β-NaYF4 UCNPs, which serve as solid-state gain media. In this scheme, the cooling power and the stimulated emission are provided by UCNPs with different compositions operating at the same pump wavelength.

Radiation-balanced lasers that can provide lasing without detrimental heating of laser medium are a very interesting and intensively developing area of laser physics. All four designs of athermal lasers including radiation-balanced bulk and fibre lasers, radiation-balanced disk lasers, and athermal microlasers are very promising for different applications. Anti-Stokes cooling of RE-doped bulk, fibre, and disk lasers have been experimentally demonstrated. Both experiments and calculations indicate that improving the purity of host crystals will result into improving athermal laser performance. The development of new RE-doped low-phonon materials can facilitate the realization of athermal lasers and accelerate their commercialisation.

It is important to emphasize that the further average power scaling requires better control of the beam intensity profile. Athermal laser operation with mode-mismatched Gaussian and super-Gaussian beams was analyzed in [30]. As one can see in [30], in a disk geometry, beam-area scaling to high-power operations can be accompanied by large transverse temperature gradients. These undesirable gradients can be countered by pump beam shaping and/or employing longer gain media.

Considering four main designs of radiation-balanced lasers, I believe that athermal disk lasers will be the first commercially available radiation-balanced lasers.