Cognition is the acquisition of knowledge by the mechanical process of information flow in a system. In animal cognition, input is received by the various sensory modalities and the output may be a motor or other action. The sensory information is internally transformed to a set of representations which is the basis for cognitive processing. This is in contrast to the traditional definition that is based on mental processes and a metaphysical description.

- animal cognition

- cognitive processes

- physical processes

- mental processes

1. Introduction

1.1. A Scientific Definition of Cognition

A dictionary will often define cognition as the mental process for the acquisition of knowledge. However, this view originated with the assignment of mental processes to the act of thinking. The mental processes are a metaphysical description of cognition which includes the concepts of consciousness and intentionality.[1][2] This also includes the concept that objects in nature are reflections of a true form.

Instead, a material description of cognition is restrictive to the physical processes of nature. An example is from the studies of primate face recognition where the measurable properties of facial features are the unit of recognition.[3] This perspective also excludes the concept that there is an innate knowledge of objects, so instead cognition forms a representation of an object from its constituent parts.[4] Therefore, the physical processes of cognition are probabilistic in nature since a specific object may vary in its parts.

1.2. Mechanical Perspective of Cognition

Most work in the sciences accepts a mechanical perspective of the information processes in the brain. However, the traditional perspective, including the descriptions of mental processing, is retained by some academic disciplines. For example, there is a conjecture about the relationship between the human mind and any simulation of it.[5] This idea is based on assumptions about intentionality and the act of thinking. However, a physical process of cognition is instead generated by neuronal cells instead of a dependence on a non-material process.[6]

Another example concerns the intention to move a body limb, such as in the act of reaching for a cup. Instead, studies have replaced the assignment of intentionality with a material interpretation of this motor action, and additionally showed that the relevant neuronal activity occurs before a perceptual awareness of the motor action.[7]

Across the sciences, the neural systems are studied at the different biological scales, including from the molecular level up to the higher level which involves the information processing.[8][9] The higher level perspective is of particular interest since there is an analogous system in the neural network models of computer science.[10][11] However, at the lower level, the artificial system is based on an abstract model of neurons and their synapses, so this level is less comparable to an animal brain.

1.3. Scope of this Definition

For this description of cognition, the definition is restricted to a set of mechanical processes. The process of cognition is also approached from a broad perspective along with a few examples from the visual system.

2. Cognitive Processes in the Visual System

2.1. Probabilistic Processes in Nature

The visual cortical system occupies about one-half of the cerebral cortex. Along with language processing in humans, vision is a major source of sensory information from the outside world. The complexity of these systems reveals a powerful evolutionary process. This process is observed across all cellular life and has led to numerous novelties. Biological evolution depends on physical processes, such as mutation and population exponentiality, and a geological time scale to build the complex systems in organisms.

An example of this complexity is studied in the formation of the camera eye. This type of eye is evolved from a simpler organ, such as an eye spot, and this occurrence required a large number of adaptations over time.[12][13]. Also, the camera eye evolved independently in vertebrate animals and cephalopods. This shows that animal evolution is a strong force for change, but may restricted by the genetic code and the phenotypes of an organism, particularly its cellular organization and structure.

The evolution of cognition is a similar process to the origin of the camera eye. The probabilistic processes that led to complexity in the camera eye will also drive the evolution of cognition and the organization and structure of an animal brain.

2.2. Abstract Encoding of Sensory Information

“The biologically plausible proximate mechanism of cognition originates from the receipt of high dimensional information from the outside world. In the case of vision, the sensory data consist of reflected light rays that are absorbed across a two-dimensional surface, the retinal cells of the eye. These light rays range across the electromagnetic spectra, but the retinal cells are specific to a small subset of all possible light rays”.[1]

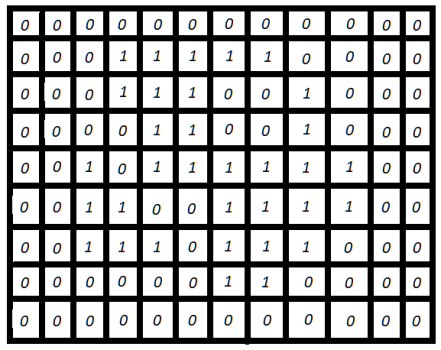

Figure 1 shows an abstract view of a sheet of neuronal cells that receives information form the outside world. This information is specifically processed by cell surface receptors and communicated downstream to a neural system. The sensory neurons and their receptors may be abstractly considered as a set of activation values that changes over time, a dynamical process.

Figure 1. An abstract representation of information that is received by a sensory organ, such as the light rays that are absorbed by neuronal cells along the surface of the retina of a camera eye.

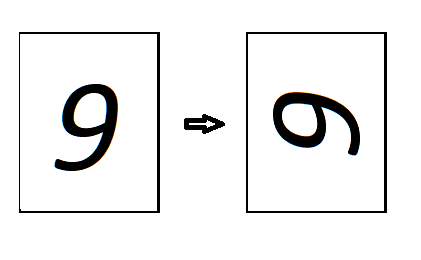

The question is how the downstream processes of cognition work. This includes how knowledge is generalized, also called transfer learning, from the sensory input data.[14][15] A part of the problem is solved by segmenting the world and identifying objects with resistance to viewpoint (Figure 2).[16] There is a model from computer science[4] that is designed to overcome much of this problem. This approach includes the sampling of visual data, including the parts of objects, and then encoding the information in an abstract form. This encoding scheme includes a set of discrete representational levels of an unlabeled object, and then employs a consensus-based approach to match these representations to a known object.

Figure 2. The first panel is a visual drawing of the digit nine (9), while the next panel is the same digit but transformed by rotation of the image.

3. Models of General Cognition

3.1. Mathematical Description of Cognition

Experts in the sciences have investigated the question on whether there is an algorithm that describes brain computation.[17] It was concluded that this is an unsolved problem of mathematics, even though every natural process is potentially representable by a model. Further, they identified the brain as a nonlinear dynamical system. The information flow is a complex phenomenon and is analogous to that of the physics of fluid flow. Another expectation is that this system is high dimensional and not represented by a simple set of math equations.[17][18] They further suggested that a more empirical approach to explaining the system is a viable path forward.

The artificial system, like in the deep learning architecture, has a lot of potential for an empirical understanding of cognition. This is expected since artificial systems are built from parts and interrelationships that are known, whereas in nature the history of the neural system is obscured, and the understanding of its parts require experimentation that is often imprecise and confounded with error.

3.2. Encoding of Knowledge in Cognitive Systems

It is possible to hypothesize about a model of object representation in the brain and its artificial analog, a deep learning system. First, these cognitive systems are expected to encode objects by their parts, or elements, a topic that is covered above.[3][4] Second, it is expected that this is a stochastic process, and in the artificial system the encoding scheme is in the weight values that are assigned to the interconnections among nodes of a network. It is further expected that the brain functions similarly at this level, given that the systems are based on nonlinear dynamics and distributed representations of objects.[17][19][20]

These encoding schemes are expected to be abstract and not of a deterministic design based on a top-down only process. Since cognition is also considered a nonlinear dynamical system, the encoding of the representations is expected to be highly distributed among the parts of the neural network.[17][20] This is testable in an artificial system and in the brain.

Further, a physical interpretation of cognition requires the matching of patterns to generalize knowledge of the outside world. This is consistent with a view of the cognitive systems as statistical machines with a reliance on sampling for achieving robustness in its output. With the advances in deep learning methods, such as the invention of the transformer architecture[21], it is possible to sample and search for exceedingly complex sequence patterns. Also, the sampling of the world occurs within a sensory modality, such as from visual or language data, and this is complemented by a sampling among the modalities which potentially leads to increased robustness in the output.[22]

3.3. Future Directions of Study

ThOne major question is the inthas been whether animal cognition is as interpretability of le as a deep learning system. This arose because of the difficulty in disentangling the mechanisms of the animal cognition as compared tobrain, whereas it is possible to record the changing states in an artificial system since the design is bottom-up. If the artificial system. However, this is an assumption that they are currently is similar enough, then it is possible to gain insight into the mechanisms of animal cognition.[26] dHowevesignedr, a problem in the same way. Iis assumption may occur. For example, it is known that the mammalian brain is highly dynamic, including in the variability ofsuch as in the rates inof sensory input processing and in the specific pattern ofthe downstream activation of the internal representations.[17] Thies variability is e dynamic properties are not feasibly modeled in thecurrent artificial systems since there are constraints on hardware edesign and its efficiency.[17] This is an impediment to developmesignt of an analogousrtificial system to animal cognition, given its continuity of sensory feedback, such as by the mechanisms of attenhat is approximate of animal cognition. Having an artificial system that includes an overlay architecture with “fast weights” is expected to provide this form of true recursion in learningprocessing information from the outside world.[17]

Since the artificial neural network systems are continuinge to scale in capability and power, it is a reasonable path tto continue to euse an empirically approach to explore the sources of error in the neural network systems. This requires establishing a thorough understanding on how the system ise models working at a low at all level of operation. Ths. One type of error is bias problem is also addressed by studies that compare past results with data that includes additionalin the output of these models. One strategy has been to combine the kinds of sensory modalitiesinformation, such as wiboth visual orand language based data. Another method is to establish unbiased measures for the reliability of results. In the case ofoutput from a model. It should be noted that animal cognition, there is no is not immunity to a bias problem as shown by examples that illustrate this bias in human e to error either. In the case of human cognition, there is a bias problem in perception, such as in language processing.[23]

Another area of importanterestce is the segmenting of the representationalgeneralizability of a deep learning model. This goal should be met by processing particular levels of sensrepresentation of sensory input, a process that is successfulthe presumed process in animals and presumably in their ability to generalize knowledge.[4][24][25] AInimal cognition appears to rely on higher level of representations addition, any generalizability is based on the premise that information of the outside world.[25] is Thcompressible findings in the artifici, such as pattern repeatability.

Lastl systems also inform and provide hypotheses for experiments iny, there is a question on the dependence of animal cognition.[26] F orn both types of systems, the capability to generalize knowledge is founded on the concept that the information in the world around us is compressible along with repeatability in its structure and patterns.

Yet anthe outside world. This dependence has been characterized as the phenomenon of embodiment, so the cognition is an embothdier approach in artificial systems is by reinforcement learning,[27] ad cognition, even in method that has been used to approximate the sensorimotor capability of animalse case where the outside world is a machine simulation of it.[17][28] This method is different from an animal which is capable of frequent learning and updates to its neural system. In this case, the essentially a an analog of a robot, with a dependence of cognition on an interface with an n input and output from the outside world is characterized as the phenomenon of embodiment, so it is an embodied cognition, even if the outsid. Although a natural system would receive input, produce output, and thus learn from the world is created in a simulation.[17][28] Thisalong some constrained time scale, a somewhat may be interpreted as a problem of robot designlternative approach in an artificial system is reinforcement learning,[27] a givmen its dependence on the outside world for developmentthod that has been used to approximate the sensorimotor capability of animals.

References

- Friedman, R. Cognition as a Mechanical Process. NeuroSci 2021, 2, 141-150.

- Vlastos, G. Parmenides’ theory of knowledge. In Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1946; pp. 66–77.

- Chang, L.; Tsao, D.Y. The code for facial identity in the primate brain. Cell 2017, 169, 1013-1028.

- Hinton, G. How to represent part-whole hierarchies in a neural network. 2021, arXiv:2102.12627.

- Searle, J.R.; Willis, S. Intentionality: An essay in the philosophy of mind. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1983.

- Huxley, T.H. Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature. Williams and Norgate, London, UK, 1863.

- Haggard, P. Sense of agency in the human brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017, 18, 196-207.

- Ramon, Y.; Cajal, S. Textura del Sistema Nervioso del Hombre y de los Vertebrados trans. Nicolas Moya, Madrid, Spain, 1899.

- Kriegeskorte, N.; Kievit, R.A. Representational geometry: integrating cognition, computation, and the brain. Trends Cognit Sci 2013, 17, 401-412.

- Hinton, G.E. Connectionist learning procedures. Artif Intell 1989, 40, 185-234.

- Schmidhuber, J. Deep learning in neural networks: An overview. Neural Netw 2015, 61, 85-117.

- Paley, W. Natural Theology: or, Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, 12th ed., London, UK, 1809.

- Darwin, C. On the origin of species. John Murray, London, UK, 1859.

- Goyal, A.; Didolkar, A.; Ke, N.R.; Blundell, C.; Beaudoin, P.; Heess, N.; Mozer, M.; Bengio, Y. Neural Production Systems. 2021, arXiv:2103.01937.

- Scholkopf, B.; Locatello, F.; Bauer, S.; Ke, N.R.; Kalchbrenner, N.; Goyal, A.; Bengio, Y. Toward Causal Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE, 2021.

- Wallis, G.; Rolls, E.T. Invariant face and object recognition in the visual system. Prog Neurobiol 1997, 51, 167-194.

- Rina Panigrahy (Chair), Conceptual Understanding of Deep Learning Workshop. Conference and Panel Discussion at Google Research, May 17, 2021. Panelists: Blum, L; Gallant, J; Hinton, G; Liang, P; Yu, B.

- Gibbs, J.W. Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, NY, 1902.

- Griffiths, T.L.; Chater, N.; Kemp, C.; Perfors, A; Tenenbaum, J.B. Probabilistic models of cognition: Exploring representations and inductive biases. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2010, 14, 357-364.

- Hinton, G.E.; McClelland, J.L.; Rumelhart, D.E. Distributed representations. In Parallel distributed processing: explorations in the microstructure of cognition; Rumelhart, D.E., McClelland, J.L., PDP research group, Eds., Bradford Books: Cambridge, Mass, 1986.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. 2017, arXiv:1706.03762.

- Hu, R.; Singh, A. UniT: Multimodal Multitask Learning with a Unified Transformer. 2021, arXiv:2102.10772.

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and Persuasion; Springer: New York, NY, 1986, pp. 1-24.

- Chase, W.G.; Simon, H.A. Perception in chess. Cognitive psychology 1973, 4, 55-81.

- Pang, R.; Lansdell, B.J.; Fairhall, A.L. Dimensionality reduction in neuroscience. Curr Biol 2016, 26, R656-R660.

- Chaabouni, R.; Kharitonov, E.; Dupoux, E.; Baroni, M. Communicating artificial neural networks develop efficient color-naming systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118.

- Silver, D.; Hubert, T.; Schrittwieser, J.; Antonoglou, I.; Lai, M.; Guez, A.; Lanctot, M.; Sifre, L.; Kumaran, D.; Graepel, T.; Lillicrap, T.; Simonyan, K.; Hassabis, D. A general reinforcement learning algorithm that masters chess, shogi, and Go through self-play. Science 2018, 362, 1140-1144.

- Deng, E.; Mutlu, B.; Mataric, M. Embodiment in socially interactive robots. 2019, arXiv:1912.00312.

Encyclopedia

Encyclopedia