1000/1000

Hot

Most Recent

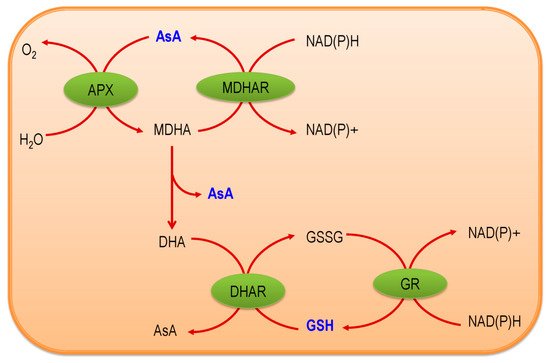

The Ascorbate-Glutathione (AsA-GSH) pathway, also known as Asada–Halliwell pathway comprises of AsA, GSH, and four enzymes viz. ascorbate peroxidase, monodehydroascorbate reductase, dehydroascorbate reductase, and glutathione reductase, play a vital role in detoxifying ROS. Apart from ROS detoxification, they also interact with other defense systems in plants and protect the plants from various abiotic stress-induced damages. Several plant studies revealed that the upregulation or overexpression of AsA-GSH pathway enzymes and the enhancement of the AsA and GSH levels conferred plants better tolerance to abiotic stresses by reducing the ROS.

| Plant Species | Stress Levels | Status of AsA-GSH Component(s) | ROS Regulation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triticum aestivum L. | 100 mM NaCl | GSH content increased by 15%; Stimulated APX and GR activities by 78% and 56%, respectively | Increased H2O2 content about 79% | [11] |

| T. aestivum L. cv. BARI Gom-21 | 12% PEG for 48 and 72 h | Decreased AsA content at 48 h, but after 72 h, AsA content again enhanced; Increased GSH and GSSG content where GSH/GSSG ratio decreased time-dependently; Enhanced the activities of APX, MDHAR, and GR | Enhanced the H2O2 content by 62% and increased O2− accumulation | [12] |

| T. aestivum L. | 10% PEG | Reduced AsA/DHA and GSH/GSSG redox; Increased enzymatic antioxidants actions of AsA-GSH cycle | Increased H2O2 production | [13] |

| T. aestivum L. | 35–40% field capacity (FC) water | Increased GSH/GSSG by 64% while decreased AsA/DHA by 52% respective with a duration of stress; Enhanced APX, MDHAR, DHAR and GR activities | Increased H2O2 along with stress duration | [14] |

| T. aestivum cv. Pradip | 150 and 300 mM NaCl | Reduced AsA content upto 52%; Increased reduced and oxidized GSH accumulation by 55% and 18%, respectively with 32% higher GSH/GSSG ratio; Increased APX activity with 29% reduction of GR activity; Slightly increased MDHAR and DHAR activity | Enhanced H2O2 generation by 60% | [15] |

| Oryza sativa L. cv. BRRI dhan47 | 150 mM NaCl | Increased GSH accumulation while reduced AsA content by 49% Increased GSH content and lowered the redox status of both AsA/DHA and GSH/GSSG; Upregulated the activity of APX, MDHAR, DHAR, and GR |

Increased the production of O2− with 82% higher H2O2 accumulation | [16] |

| O. sativa L. cv. BRRI dhan49 | 300 mM NaCl | Reduced AsA and GSH accumulation by 51% and 57%, respectively; Decrease GSH/GSSG redox by 87%; Showed lowered APX (27%), MDHAR (24%), DHAR and GR (25%) activities | Increased H2O2 content upto 69% | [17] |

| O. sativa L. cv. BRRI dhan54 | 300 mM NaCl | Improved AsA content by 51% with higher GSH content; Decreased GSH/GSSG ratio by 53%; Showed higher APX (27%) and DHAR activities while decreased both GR (23%) and MDHAR activities | Accumulated 63% higher H2O2 content | [17] |

| Brassica napus L. cv. BinaSharisha-3 | 100 and mM NaCl | Reduced the AsA content by 22%; Increased GSH content by 72% and GSSG content by 88%; Unaltered the GSH/GSSG ratio; Amplified APX activity by 32%, decreased DHAR activity by 17%; Slightly increased GR activity | Accumulated higher H2O2 content by 76% | [18] |

| B. napus L. cv. Binasharisha-3 | 200 mM NaCl | Reduced the AsA content (40%) along with increased GSH (43%) and GSSG (136%) contents; Decreased the GSH/GSSG ratio (40%); Amplified the APX activity (39%) and reduced the MDHAR (29%) and DHAR (35%) activities; Improved GR activity (18%) | Showed 90% more H2O2 content | [18] |

| B. napus L. | 15% PEG | The AsA accumulation remained unaltered and reduced the AsA/DHA ratio; Enhanced GSH content by 19% and GSSG by 67% and decreased GSH/GSSG ratio; Increased APX, MDHAR, DHAR and GR activities | Higher accumulation of H2O2 by 55% | [19] |

| B. campestris L. | 15% PEG | Decreased AsA content by 27% with a decrease of AsA/DHA ratio; Increased GSH content by 33% with higher GSSG content by 79% and lowered GSH/GSSG ratio; Decreased DHAR activity | Higher accumulation of H2O2 about 109% | [19] |

| B. juncea L. | 15% PEG | Increased the AsA content and did not affect the AsA/DHA ratio; Increased GSH content by 48% and GSSG by 83% and decreased GSH/GSSG ratio; Increased APX, MDHAR, DHAR and GR activities | Accumulation of 37% higher H2O2 | [19] |

| B. juncea L. cv. BARI Sharisha-11 | 10% PEG | Reduced AsA content (14%) while increased both GSH (32%) and GSSG (48%) contents; Enhanced APX activity (24%); Decreased MDHAR and DHAR (33%) activities along with 31% increased GR activity | Acute generation of H2O2 (41%) | [20] |

| B. juncea L. cv. BARI Sharisha-11 | 20% PEG | Decreased AsA content by 34% while increased the content of GSH by 25% and GSSG by 101%; Up-regulated APX activity by 33%; Decreased activity of MDHAR and DHAR (30%) | Extreme generation of H2O2 by 95% | [20] |

| B. napus L. cv. BinaSarisha-3 | 10% PEG | Increased AsA (21%), GSH (55%) and GSSG contents while decreased GSH/GSSG ratio Unaltered the activities of APX, and increased the activity of MDHAR, DHAR, and GR (26%) | Elevated the H2O2 production | [8] |

| B. napus L. cv. BinaSarisha-3 | 20% PEG | Unaltered AsA content along with higher content of GSH (46%) and GSSG and reduced GSH/GSSG ratio; Reduced the APX and MDHAR activities along with the higher activity of DHAR and GR (23%) | Showed higher H2O2 production | [8] |

| B. napus L. cv. BinaSharisha-3 | 10% PEG | Increased AsA, GSH (31%) and GSSG (83%) accumulation with lowered GSH/GSSG ratio; Increased APX activity while reduced MDHAR and DHAR activities, but GR activity remained unaltered | Increased H2O2 content by 53% | [21] |

| B. napus L. cv. BinaSharisha- 3 | 20% PEG | Slightly increased AsA content with 26% and 225% increase of GSH and GSSG content, respectively; Reduced GSH/GSSG ratio; Increased APX activity while decreased the activity of MDHAR, DHAR, and GR (30%) | Increased about 93% H2O2 content | [21] |

| B. rapa L. cv. BARI Sharisha-15 | 20% PEG | Slightly increased AsA content with 72% and 178% increase of GSH and GSSG content, respectively; Reduced GSH/GSSG ratio by 38%; Increased APX, MDHAR, DHAR, and GR activity | Increased about 131% H2O2 content | [22] |

| Cucumis melo L. cv. Yipintianxia No. 208 | 50 mM of NaCl:Na2SO4:NaHCO3:Na2CO3 (1:9:9:1 M) | Improved AsA, GSSG and DHA contents; Lowered GSH content; Reduced the ratio of AsA/DHA and GSH/GSSG; Stimulated the activity of APX by 96% and DHAR by 38% while reducing the activity of MDHAR and GR by 48% and 34%, respectively | Increased H2O2 accumulation | [23] |

| Solanum lycopersicum L., var. Lakshmi | 0.3 and 0.5 g NaCl kg−1 soil | Reduced AsA and AsA/DHA ratio; Lowered GSH and GSSG accumulation with decreased GSH/GSSG redox; Increased APX activity by 28%, DHAR activity by 28% and GR activity by 14% | Enhanced H2O2 and O2− accumulation | [24] |

| S. lycopersicum L.cv. Boludo | 60 mM NaCl, 30 days | Reduced the activities of APX, DHAR, and GR; Increased MDHAR activity | Higher H2O2 generation | [25] |

| S. lycopersicum L. var. Pusa Ruby | 150 mM NaCl | Decreased AsA and GSH content with a higher content of DHA and GSSG; Increased APX, MDHAR, DHAr and GR activities | Higher generation of H2O2 and O2− | [26] |

| S. lycopersicum L. var. Pusa Rohini | 150 mM NaCl | Reduced AsA content by 42%; Increased both GSH and GSSG accumulation; Enhanced the activity of APX and GR by 86% and 29%, respectively with reduction of the activity of MDHAR and DHAR by 38% and 32%, respectively | Accumulated about 3 fold higher H2O2 content | [27] |

| S. lycopersicon L. cv.K-21 | 150 mM NaCl | Reduced AsA content by 40% with 50% higher GSH content; Lowered GSSG content by 23% while increased GSH/GSSG ratio by 112%; Increased APX (86%) and GR (92%) activity along with the lowered activity of MDHAR (32%) and DHAR (30%) | Elevated H2O2 content about 175% | [28] |

| Nitraria Tangutorum Bobr. | 100,200, 300 and 400 mM NaCl | Increased AsA, DHA, GSH and GSSG accumulation decreased their redox status; Enhanced the activity of APX and GR; Unvaried the activity of DHAR and MDHAR but increased DHAR activity only at 300 mM NaCl | Increased O2−and H2O2 content by 38–98 and 49–102% respectively | [29] |

| Camellia sinensis (L.) O.Kuntze | 300 mM NaCl | Enhanced the AsA and GSH content; Increased APX activity | Elevated H2O2 and O2− content | [30] |

| Phaseolus vulgaris L. cv. Nebraska | 2.5 and 5.0 dS m–1 prepared from a mixture of NaCl, CaCl2, and MgSO4 | Increased AsA, GSH, DHA and GSSG accumulations; Enhanced AsA/DHA and GSH/GSSG status; Stimulated the enzymatic activity of APX, MDHAR, DHAR and GR activities | Accumulated higher H2O2 content | [31] |

| Vigna radiate L. cv. Binamoog-1 | 25% PEG | Reduced AsA content along with higher GSH content of 92%; Increased GSSG content by 236% and reduced GSH/GSSG ratio; Amplified the activity of APX (21%) and GR while reduced MDHAR and DHAR activities | Elevated H2O2 content by 114% with higher O2− generation | [32] |

| V. radiata L. | 200 mM NaCl | Reduced AsA content; Increased GSSG and GSH accumulation and lowered GSH/GSSG ratio; Amplified the activity of APX, MDHAR, DHAR, and GR | Increased H2O2 content by 80% and O2− generation by 86% | [33] |

| V. radiata L. cv. BARI Mung-2 | 5% PEG | Reduced AsA content where decreased AsA/DHA ratio by 54%; Increased GSSG content; Upregulated the activity of APX and GR (42%) while downregulated the MDHAR (26%) and DHAR activities | Elevated H2O2 and O2− accumulation | [34] |

| Lens culinaris Medik cv. BARI Lentil-7 | 20% PEG | Lowered AsA content with higher total GSH content; Unaltered the APX and GR activities while the increased activity of MDHAR and DHAR (64%) | Accumulated higher H2O2 content | [35] |

| L. culinaris Medik cv. BARI Lentil-7 | 100 mM NaCl | Reduced AsA content by 87% while increased total GSH content by 260%; Improved the activity of APX, MDHAR, DHAR (286%) and GR (162%) | Increased H2O2 content by 15% | [35] |

| Anacardium occidentale L. | 21-day water withdrawal | Enhanced total AsA and GSH content; Increased APX activity | Reduced H2O2 generation | [36] |

| Arabidopsis | 12-day water withhold | Showed higher GSH and GSSG accumulation; Reduced GSH/GSSG ratio; Increased GR activity | Increased H2O2 accumulation rate | [37] |

| Cajanus cajan L. | Complete water withholding for 3, 6 and 9 days | Decreased GSH/GSSG ratio; Increased the activity of APX, DHAR, and GR | Higher H2O2 content | [38] |

| Amaranthus tricolor L.cv. VA13 | 30% FC | Increased AsA and GSH contents by 286% and 98%, respectively; Improved APX, MDHAR, DHAR, and GR activity by 371%, 379%, 375%, and 375%, respectively | No increment of H2O2 content | [39] |

| A. tricolor L.cv. VA15 | 30% FC | Increased AsA and GSH contents along with higher redox status of AsA/total AsA and GSH/total GSH; Enhanced the activity of APX, MDHAR, DHAR, and GR by 37%, 45%, 40%, and 2%, respectively | Accumulated higher H2O2 content by 137% | [39] |

| C. sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze | 20% PEG | Higher contents of both AsA and GSH; Enhanced the APX activity | Higher accumulation of H2O2 and O2− | [30] |

| Plant Species | Stress Levels | Status of AsA-GSH Component(s) | ROS Regulation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brassica napus L. cv. BinaSharisha-3 | Cd (0.5 mM and 1.0 mM CdCl2), 48 h | Reduced AsA content by 20% under 0.5 mM and 32% under 1.0 mM CdCl2 treatment; Increased GSH content only under 0.5 mM CdCl2 stress but enhanced level of GSSG by 34% under 0.5 mM and 65% under 1.0 mM CdCl2 treatment; Increased function of APX by 39% and 43% under 0.5 mM and 1.0 mM CdCl2 treatment but MDHAR and DHAR activity were diminished in dose dependant fashion; GR activity increased by 66% due to 0.5 mM CdCl2 treatment but reduced by 24% due to 1.0 mM CdCl2 treatment | Enhanced H2O2 content by 37% under 0.5 mM and 60% under 1.0 mM CdCl2 treatment | [40] |

| Gossypium spp. (genotype MNH 886) | Pb [50 and 100 μM Pb(NO3)2], 6 weeks | Increased APX activity | Increased H2O2 content | [41] |

| T. aestivum L. cv. Pradip | As (0.25 and 0.5 mM Na2HAsO47H2O), 72 h | Reduced AsA content by 14% under 0.25 and 34% underd 0.5 mM Na2HAsO4·7H2O treatment; Increased GSH content by 46% and 34%, GSSG content by 50 and 101% under 0.25 and 0.5 mM Na2HAsO4·7H2O stress; Enhanced APX function by 39% and 43% but decreased DHAR function by 33% and 30% under 0.25 and 0.5 mM Na2HAsO4·7H2O treatment; Increased GR function by 31% under 0.25 mM | Increased H2O2 content by 41% under 0.25 and 95% under 0.5 mM Na2HAsO4·7H2O treatment | [42] |

| B. napus L. viz. ZS 758, Zheda619, ZY 50 and Zheda 622 | Cr (400 µM), 15 days | Increased GSH and GSSG content; Increased APX activity | Increased H2O2 content | [43] |

| Oryza sativa L. cv. BRRI dhan29 | As (0.5 mM and 1 mM Na2HAsO4), 5 days | Decreased AsA content by 33 and 51% and increased DHA content by 27% and 40% under 0.5mM and 1mM Na2HAsO4 treatment, respectively; Decreased ratio of AsA/DHA; Enhanced GSH content by 48 and 82% under 0.5mM and 1mM Na2HAsO4 treatment, respectively; Enhanced GSSG content whereas lessened GSH/GSSG ratio by 25% under 0.5mM and 41% under 1mM Na2HAsO4 treatment; Augmented the function of APX, MDHAR, and GR, however, reduced the activity of DHAR | Increased H2O2 content by 65% and 89% under 0.5mM and 1mM Na2HAsO4 treatment, respectively | [44] |

| O. sativa L. cv. Disang (tolerant) | 100 µM AlCl3, 48 h | Increased AsA content in both roots and shoots; Enhanced the GSH content in shoots; Higher activities of APX, MDHAR, DHAR, and GR, | Elevated the generation of H2O2 and O2− | [45] |

| O. sativa L. cv. Joymati (sensitive) | 100 µM AlCl3, 48 h | Higher accumulation of AsA in both roots and shoots; Reduced the GSH content in roots while shoots content was unaltered; Increased APX, MDHAR, DHAR activities; Slightly increased GR activities | Higher accumulation of H2O2 and O2− | [45] |

| V. radiata L. cv. BARI Mung-2 | Cd (mild: 1.0 mM CdCl2, severer: 1.5 mM CdCl2), 48 h | Declined AsA content by 31% due to mild and 41% due to severe stress; Enhanced DHA level and reduced AsA/DHA ratio; GSH content did not change due to mild stress but enhanced owing to stress severity; GSSG level enhanced, and GSH/GSSG ratio decreased in a dose-dependent manner; Increased function of APX but lessened MDHAR and DHAR function due to both level of stress; GR activity increased only due to severe stress | H2O2 level and O2− generation rate was augmented by 73% and 127% due to mild and 69% and 120% due to severe Cd stresses | [46] |

| V. radiata L. cv. BARI Mung-2 | Cd (1.5 mM CdCl2), 48 h | AsA content decreased by 27%, and the ratio of AsA/DHA reduced by 80% whereas DHA content increased considerably; Augmented the function of APX and GR however lessened function of MDHAR and DHAR | Increased H2O2 level and O2− generation rate | [47] |

| O. sativa L. cv. BRRI dhan29 | Cd (0.25 mM and 0.5 mM CdCl2), 3 days | AsA content and AsA/DHA ratio reduced by 37% and 57% due to 0.25 mM CdCl2 and reduced by 51% and 68% due to 0.5 mM CdCl2, respectively; DHA content increased significantly; GSH content enhanced due to 0.25 mM CdCl2 stress, but reduced due to 0.5 mM CdCl2 stress; GSSG content enhanced by 76% under 0.25 mM and 108% under 0.5 mM CdCl2 stress; Reduced ratio of GSH/GSSG in dose dependant manner; Enhanced APX, MDHAR and GR activity | Enhenced H2O2 by 46% under 0.25 mM CdCl2 and 84% under 0.5 mM CdCl2 treatmen whereas O2− generation rate increased in dose dependant manner | [48] |

| O. sativa L. cv. BRRI dhan29 | Cd (0.3 mM CdCl2), 3 days | Lessened level of AsA and AsA/DHA ratio but enhanced DHA level; Enhanced the level of GSH and GSSG however lessened GSH/GSSG ratio; Enhanced the action of APX, MDHAR, and GR whereas declined DHAR function | Overproduced ROS (H2O2 and O2−) | [49] |

| O. sativa L. Zhunliangyou 608 | Cd (5 μM Cd(NO3)2·4H2O), 6 days | Reduced AsA content; Increased GSH content; Slightly reduced the APX activity | H2O2 content increased by 22.73% | [50] |

| Abelmoschus esculentus L. Moench | Pb (100 mg L−1), 21 days | Increased AsA content | Enhanced H2O2 content | [51] |

| B. juncea L. cv. BARI Sharisha-11 | Cr (mild: 0.15 mM K2CrO4, severe: 0.3 mM K2CrO4), 5 days | AsA content lessened by 19% due to mild and 32% due to severe stress whereas DHA level enhanced by 83% due to mild and 133% due to severe stress as well as AsA/DHA ratio lessened by 47% due to mild and 82% due to severe stress; GSH content did not change considerably but GSSG content enhanced by 42% due to mild and 67% due to severe stress as well as GSH/GSSG ratio lessened by 26% due to mild and 41% due to severe stress; The function of APX enhanced by 21% due to mild and 28% due to severe stress; The activity of MDHAR and DHAR reduced by 25 and 32% under mild and 31 and 50%, under severe stress, respectively; Mild stress increased the activity of GR by 19% while severe stress increased by 16% | H2O2 level enhanced by 24% and 46% due to mild and severe stress. Similarly, O2− generation rate also raised in a dose-dependent manner | [52] |

| B. campestris L. cv. BARISharisha 9, B. napus L. cv. BARI Sharisha-13 and B. juncea L. cv. BARI Sharisha-16 | Cd (mild: 0.25 mM CdCl2, severer: 0.5 mM CdCl2), 3 days | Decreased level ofAsA, augmented level of DHA as well as decreased AsA/DHA ratio in all studied cultivars; GSH and GSSG level enhanced, but GSH/GSSG ratio lessened in all studied cultivars; APX and GR activities of all species increased significantly under both levels of Cd toxicity | Enhanced H2O2 level and O2− production rate in all tested cultivars in a concentration-dependent fashion | [53] |

| B. juncea L. BARI Sharisha-11 | Cd (mild: 0.5 mM CdCl2, severer: 1.0 mM CdCl2), 3 days | Reduced AsA content with higher DHA content and thus decreased AsA/DHA ratio; Increased GSH and GSSG levels as well as declined GSH/GSSG ratio; APX activity increased where GR increased at mild stress but remained unaltered at severe stress; Decreased MDHAR and DHAR activities | Enhanced the H2O2 and O2−level | [54] |

| V. radiata L. cv. BARI Mung-2 | Al (AlCl3, 0.5 mM), 48 and 72 h | Enhanced DHA content but reduced AsA level and AsA/DHA ratio; Increased level of GSH and GSSG but the diminished ratio of GSH/GSSG; Augmented APX activity but decreased MDHAR and DHAR activity | Enhanced H2O2 level by 83% and O2− generation rate by 110% | [34] |

| T. aestivum L. cv. Pradip | Pb [mild: 0.5 mM Pb(NO3)2, severer: 1.0 mM Pb(NO3)2], 2 days | AsA decreased in a dose-dependent manner; Mild stress improved the GSH level, but severe stress reduced it; Increased GSSG content; Increased APX activity; Diminished activity of MDHAR and DHAR in a concentration-dependent fashion; Mild stress improved GR activity but severe stress reduced it | Mild stress increased H2O2 levels by 41%, but severe stress enhanced it by 95% while O2− generation rate also increased in a dose-dependent manner | [55] |

| B. juncea L. cv. BARI Sharisha-11 | Cd (mild: 0.5 mM CdCl2, severer: 1.0 mM CdCl2), 3 days | AsA content decreased by 24% due to mild and 42% due to severe stress whereas DHA level enhanced by 79% due mild and 200% due to severe stress; Decreased AsA/DHA ratio in dose-dependent manner; GSH and GSSG content enhanced by 19% and 44%, respectively, due to mild stress, while only GSSG content enhanced due to severe stress by 72%; The ratio of GSH/GSSG declined by 17% due to mild and 43% due to severe stress; Enhanced APX by 15% due to mild and 24% due to severe stress; The activity of MDHAR and DHAR reduced by 12% and 14% due to mild stress whereas 17% and 24%, due to severe stress, respectively; The activity of GR enhanced under mild stress by 16% and lessened under severe stress by 9% | Level of H2O2 enhanced by 43% due to mild and 54% due to severe stress. Augmented O2− generation rate in a dose-dependent manner | [56] |

| B. juncea L. cv. varuna | Ni, (150 μM NiCl2.6H2O), 1 week | AsA content decreased by 61% whereas GSH and GSSG content increased by 75% and 151%, respectively; Enhanced function of APX by 60% and GR by 72%; DHAR and MDHAR activities were decreased by 62% and 65%, respectively | Increased H2O2 by 3.23-fold | [57] |

| Pisum sativum L. cv. Corne de Bélier | Pb (500 mg PbCl2 kg−1), 28 days | Increased APX and GR activity | Increased H2O2 content | [58] |

| O. sativa L. cv. BRRI dhan54 | Ni (0.25 mMand 0.5 mM NiSO4·7H2O) | Diminished content of AsA and enhanced content of DHA as well as the lessened ratio of AsA/DHA by 73% and 92% under 0.25 mM and 0.5 mM NiSO4·7H2O stress; GSH and GSSG level enhanced in a dose-dependent manner. However, the GSH/GSSG ratio reduced only under 0.5 mM NiSO4·7H2O treatment; Increased APX, MDHAR, DHAR and GR activity by 70%, 61%, 19% and 37% under 0.25 mM NiSO4·7H2O and 114%, 115%, 31% and 104% under 0.5 mM NiSO4·7H2O treatment, respectively | Increased H2O2 content by 28% and 35% due to 0.25 mM and 0.5 mM NiSO4·7H2O treatment | [59] |

| Capsicum annuum L.cv. Semerkand | Cd (0.1 mM CdCl2), 3 weeks | Enhanced AsA and GSH content | Increased H2O2 content | [60] |

| C. annuum L. cv. Semerkand | Pb (0.1 mM PbCl2), 3 weeks | Enhanced AsA and GSH content | Increased H2O2 content | [60] |

| Zea mays L. cv. Run Nong 35 and Wan Dan 13 | Cd (50 mg 3CdSO4·8H2O kg−1 soil), 6 months | Decreased GSH content | Increased accumulation of H2O2 | [61] |

| Plant Species | Stress Levels | Status of AsA-GSH Component(s) | ROS Mitigation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinidia deliciosa | 45 °C, 8 h | Increased content of AsA; Higher activity of APX, MDHAR, DHAR, and GR | Increased H2O2 content | [62] |

| Zea mays L. cv. Ludan No. 8 | 46 °C, 16 h | Decreased GSH, and GSSG content, but interestingly GSH/(GSH + GSSG) ratio increased; Reduced GR activity | - | [63] |

| Cinnamonum camphora | 40 °C, 2 days | Reduced AsA content with higher DHA content; Increased GSH and GSSG content; Enhanced the activities of APX, MDHAr, DHAR, and GR | Higher content of H2O2 and O2− | [64] |

| S. lycopersicum L. cv. Ailsa Craig | 40 °C, 9 h | Higher APX and GR activities by 74% and 45%, respectively | H2O2 content increased by 49% | [65] |

| S. lycopersicum L.cv. Boludo | 35 °C, 30 days | Increased the APX, DHAR and GR activities; Reduced the MDHAR activity | Increased H2O2 content | [25] |

| Vicia faba L. cv. C5 | 42 °C, 48 h | Enhanced the AsA, GSH ans GSSG content significantly; The enzymatic activity of APX and GR also enhanced | Extreme accumulation of O2− and H2O2 | [66] |

| V.radiata L. cv. BARI Mung-2 | 40 °C, 48 h | Decreased 64% in AsA/DHA ratio; GSSG pool increased; Higher APX (42%) and GR (50%) activities but declined activities of MDHAR (17%) and DHAR | Higher H2O2 content and O2−production rate | [34] |

| Z. mays cv. CML-32 and LM-11 | 40 °C, 72 h | Increased AsA content in both shoot and root of tolerant (CML-32) one, but unaffected in the susceptible (LM-11) one; Both APX and GR activity increased in roots of CML-32 but reduced in the shoot | Higher H2O2 accumulation, especially in shoots | [67] |

| L. esculentum Mill. cv. Puhong 968 | 38/28 °C day/night, 7 days | AsA+DHA and DHA increased by 220% and 99% respectively; AsA/DHA ratio decreased by 33%.; Higher GSSG (25%), but reduced GSH content (23.4%) and GSH/GSSG ratio (39%); APX, MDHAR, DHAR and GR activities declined | Enhanced O2− generation rate and H2O2 content by 129% and 33% respectively | [68] |

| Nicotiana tabacum cv. BY-2 | 35 °C, 7 days | Total GSH and AsA contents rose after 7 days heat stress; Increased MDHAR. DHAR and GR activities up to 72 h | The increasing trend of H2O2 generation was observed up to 72 h, and then a sharp decline occurred | [69] |

| Ficus concinna var. subsessilis | 35 °C and 40 °C, 48 h | AsA content reduced at 40 °C but GSH content similar to control at both 35 and 40 °C; DHA content enhanced by 49% at 35 °C and by 70% at 40 °C; APX activity increased by 51% and 30% at 35 °C and 40 °C; Activities of MDHAR, DHAR, and GR increased at 35 °C, but GR activity decreased by 34% at 40 °C | At 35 °C, 103% higher H2O2 content and 58% higher O2−production rate and at 40 °C those were 3.3- and 2.2-fold respectively | [70] |

| T. aestivum cv. Hindi62 and PBW343 | Heat stress environment, Late sown (Mid-January) | Higher activities of MDHAR and DHAR was observed in heat-tolerant (Hindi62) one whereas other enzyme activities seemed mostly to decline with time | The content of H2O2 was higher up to 14 DAA compared to non-stressed seedlings | [67] |

| G. hirsutum cv. Siza | Waterlogged pot for 3 days and 6 days | Increased content of AsA by 20% at 3 days and 30% at 6 days of waterlogging; Lower APX, MDHAR and GR activities | Enhanced O2− generation rate by 22 and 53% and H2O2 content by 10 and 39% at 3 and 6 days of waterlogging, respectively | [63] |

| Sesamum indicum L. cv. BARI Til-4 | Waterlogged pot by 2 cm standing water on the soil surface for 2, 4, 6 and 8 days | Reduced AsA content upto 38%; Enhanced GSH and GSSG content significantly; Increased APX and MDHAR activities; Reduced DHAR activity upto 59%; GR activity decreased upto 23% | Increased H2O2content sharply | [71] |

| Z. mays cv. Huzum-265 and Huzum-55 | Root portions waterlogged for 21 h | Reduced AsA content in both cultivars; Increased APX activity in both cultivars | - | [72] |

| Glycine max L. | Waterlogged pot for 14 days | GSH activity declined sharply in roots but shoots unaffected; Reduced GR activity in shoots but roots unaffected | - | [73] |

| Trifolium repens L. cv. Rivendel and T. pratense L. cv. Raya | 2 cm standing water on the soil surface for 14 days and 21 days | Increased contents of both oxidized and reduced AsA observed in both genotypes | Higher H2O2 generation in both genotypes | [74] |

| V. radiata L. cvs. T-44 and Pusa Baisakhi; and V. luteola | Pot filled with water to 1–2 cm height below the soil level, 8 days | Increased activities of both APX and GR in tolerant genotypes but in susceptible one, activities reduced | Reduced contents of O2−and H2O2 in susceptible (Pusa Baisakhi) cultivar | [75] |

| O. sativa L. MR219-4, MR219-9 and FR13A | Complete submergence for 4, 8 and 12 days | APX activity declined by 88% in FR13A under 4 days of submergence but decreased about 64 and 83% under 8 and 12 days of submergence; GR activity increased in FR13A and MR219-4 cultivars by 10- and 13-fold respectively after 8 days | - | [76] |

| Allium fistulosum L. cv. Erhan | Waterlogging (5 cm) at substrate surface for 10 days | Lower APX and GR activities | Increased rate of O2− generation by 240.4% and 289.8% higher H2O2 content | [77] |

| C. cajan L. genotypes ICPL 84,023 and ICP 7035 | Soil surface waterlogged (1–2 cm) for 6 days | Reduced APX and GR activities in susceptible genotype, which was higher in tolerant one | Lower accumulation of H2O2 and rate of O2− generation | [78] |

| S. melongena L. cv. EG117 and EG203 | Flooding with a water level of 5 cm, 72 h | Increased AsA content in susceptible EG117 genotype GSH content in both genotypes; Increased APX activity but decreased GR activity | - | [79] |

| S. lycopersicum cv. ASVEG and L4422 | Flooding with a water level of 5 cm, 72 h | Increase in both AsA and GSH contents; Non-significant changes in APX and GR activities | - | [79] |

| Lolium perenne | Grown in an area with high air pollution | APX and DHAR activities decreased while MDHAR and GR activities increased | A higher concentration of H2O2 in pollens | [80] |

| Populus deltoides × Populus nigra cvs. Carpaccio and Robusta | O3 treatment (120 nmol mol−1 for 13 h), 17 days | No impact on AsA and GSH contents; DHAR activity decreased while GR and MDHAR activity increased | - | [81] |

| Fragaria x anansa | High dose of carbon monoxide (CO) nitroxide (NOx) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) | The activity of both APX and GR increased upto medium dose but reduced under high dose | H2O2 content as well as O2− generation rate increased | [82] |

| O. sativa L. cvs. SY63 and WXJ14 | Continuous O3 exposure for up to 79 days | Both AsA and GSH contents are more likely to decrease; APX, MDHAR, DHAR, and GR activity increased up to 70 days of O3 exposure | Both O2− generation rate and H2O2 contents increased | [83] |

| Prosopis juliflora | Grown in the polluted industrial region | The content of AsA and APX activity increased under polluted environment | - | [84] |

| Erythrina orientalis | Grown in a polluted industrial area | Increased activities of both APX and GR enzymes recorded | - | [85] |

| T. aestivum L. cv. BARI Gom-26 | Acidic pH (4.5) of growing media | Increased AsA and GSH content; Improved redox balance of GSH/GSSG; Increased activity of APX, MDHAR, DHR, and GR | H2O2 contents increased by 209% | [86] |